Ali al-Hadi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ali al-Hadiعَلِيّ ٱلْهَادِي |

|

|---|---|

| Personal | |

| Born | c. 7 March 828 CE (16 Dhu al-Hijja 212 AH) Medina, Abbasid Empire |

| Died | c. 21 June 868 (aged 40) (26 Jumada al-Thani 254) Samarra, Abbasid Empire |

| Cause of death | Poisoned by the Abbasids (most Shia sources) |

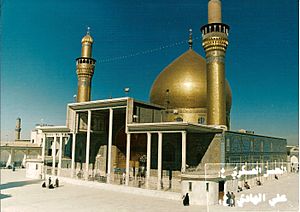

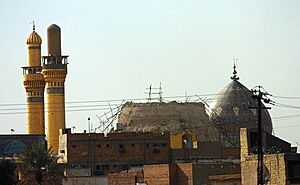

| Resting place | Al-Askari shrine, Samarra 34°11′54.5″N 43°52′25″E / 34.198472°N 43.87361°E |

| Spouse | Hudayth (or Susan or Salil) |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Senior posting | |

| Title | al-Hadi (lit. the guide) an-Naqi (lit. the distinguished) |

| Part of a series on Shia Islam |

| Twelvers |

|---|

|

Principles

|

|

Other beliefs

|

|

Other practices

|

|

Groups

|

|

Other related sects & groups

|

|

Hadith collections

|

|

|

Related topics

|

Ali al-Hadi (born 828 CE, died 868 CE) was an important religious leader in Islam. He was a descendant of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Ali al-Hadi was the tenth of the Twelve Imams for Shia Muslims. He became Imam after his father, Muhammad al-Jawad.

He is known by the titles al-Hadi (meaning "the guide") and al-Naqi (meaning "the distinguished"). Like many Imams before him, he mostly stayed away from politics. He focused on teaching in Medina.

Around 848 CE, the Abbasid Caliph al-Mutawakkil called Ali al-Hadi to the capital city of Samarra. The Caliph was known for being very strict against Shia Muslims. Ali al-Hadi was kept under close watch in Samarra until he passed away about twenty years later in 868 CE. Many Shia sources believe the Abbasids were responsible for his death. He was about forty years old.

His son, Hasan, became the next Imam. Hasan was also kept under watch in Samarra until his death in 874 CE. The al-Askari shrine in Samarra is a very important place for Shia pilgrims. It holds the tombs of Ali al-Hadi and his son. Ali al-Hadi's life in Samarra, where he was not free to lead openly, marked a change for the Shia community.

Contents

Who Was Ali al-Hadi?

Ali ibn Muhammad was known by the titles al-Hadi (meaning "the guide") and al-Naqi (meaning "the distinguished"). In Shia religious writings, he is also called Abu al-Ḥasan al-Thaleth (meaning "Abu al-Hasan, the third"). This name helped people tell him apart from earlier Imams with similar names, like Musa al-Kazim and Ali al-Rida.

Ali al-Hadi's Life Story

Growing Up and Early Years

Ali al-Hadi was born on March 7, 828 CE. His birthplace was Sorayya, a village near Medina. This village was started by his great-grandfather, Musa al-Kazim. Shia Muslims celebrate his birthday on the 15th of Dhu al-Hijja. His father was the ninth Shia Imam, Muhammad al-Jawad. His mother was Samana (or Susan), who was from North Africa.

Political Times During His Imamate

Ali al-Hadi lived during the rule of several Abbasid caliphs. These included al-Mu'tasim, al-Wathiq, al-Mutawakkil, al-Muntasir, al-Musta'in, and al-Mu'tazz.

During the early years, under Caliphs al-Mu'tasim and al-Wathiq, Ali al-Hadi and Shia Muslims had some freedom. He lived in Medina and taught many students. These students came from places like Iraq, Persia, and Egypt.

Challenges Under Caliph al-Mutawakkil

The rule of Caliph al-Mutawakkil (847-861 CE) was very difficult for Shia Muslims. Al-Mutawakkil strongly disliked Shia beliefs. He even ordered the shrine of Husayn, Ali's grandson, to be destroyed in Karbala. He wanted to stop Shia pilgrimages there.

The governor of Medina told al-Mutawakkil that Ali al-Hadi was causing trouble. Ali al-Hadi wrote to the Caliph to defend himself. The Caliph then asked Ali al-Hadi and his family to move to Samarra. Samarra was the capital city of the Abbasids at that time. It was also a military town.

Ali al-Hadi arrived in Samarra on May 1, 848 CE. The Caliph did not meet him right away. Instead, Ali al-Hadi was given a house in the army part of the city. He lived in Samarra under constant watch for about twenty years until his death. Some historians say he was like a prisoner. However, he was allowed to move around the city. He also kept in touch with his representatives. These representatives helped him communicate with Shia Muslims and receive donations.

Later Caliphs and Continued Surveillance

After al-Mutawakkil died in 861 CE, Ali al-Hadi continued to live in Samarra. He remained there through the short reigns of al-Muntasir and al-Musta'in. He passed away in 868 CE during the rule of Caliph al-Mu'tazz.

Becoming an Imam

After his father, al-Jawad, passed away in 835 CE, most of his followers accepted Ali al-Hadi as the next Imam. Ali al-Hadi was still very young, about seven years old, when he became Imam. His father had chosen him as his successor.

To make sure the community accepted him, a servant of al-Jawad, Khayran al-Khadim, said that al-Jawad had named Ali al-Hadi as his successor. Shia elders met and agreed to accept Ali al-Hadi's leadership.

His Trusted Representatives

Ali al-Hadi's time as Imam was a turning point for Shia Muslims. When he was brought to Samarra in 848 CE, the Imams could no longer directly lead the community. However, a network of representatives had already grown.

These representatives became an organized system. They helped manage the Shia community and handle money matters. One important representative was Uthman ibn Sa'id al-Asadi. He later became the first special deputy of the twelfth Imam, Mahdi.

Amazing Stories and Miracles

Shia beliefs describe Ali al-Hadi as having special knowledge. It is said he understood many languages, including Persian, Slavic, Indian, and Nabataean. People also say he could predict future events. For example, he accurately predicted the death of Caliph al-Mutawakkil.

One story tells that in front of al-Mutawakkil, Ali al-Hadi showed that a woman claiming to be Zaynab, daughter of Ali ibn Abi Talib, was not telling the truth. He did this by going into a lions' den. He said that lions would not harm true descendants of Ali. The woman refused to follow him. Another story says he brought a picture of a lion on a carpet to life. This lion then ate a juggler who was trying to make fun of Ali al-Hadi. It is also said that he once turned sand into gold for poor people.

Who Followed Him?

After Ali al-Hadi passed away, most of his followers accepted his son, Hasan, as the next Imam. Some people had thought another son, Muhammad, would be the next Imam. But Muhammad passed away before his father in Samarra.

Another son, Ja'far, also tried to claim the Imamate but was not successful. Hasan al-Askari worked to confirm his Imamate by sending letters to his followers in different areas. Shia sources say that Ali al-Hadi named Hasan as the next Imam one month before he died in 868 CE. Hasan had also been with his father in Samarra and was kept under close watch.

His Passing Away

Ali al-Hadi passed away on June 21, 868 CE. He was about forty years old. This happened during the rule of Caliph al-Mu'tazz. Shia Muslims remember his death on the 3rd of Rajab each year.

Many Shia sources believe he was poisoned by the Abbasids. However, some historical accounts do not mention the cause of his death. The Caliph's brother, al-Muwaffaq, is said to have led the funeral prayer. There were so many mourners that his family had to bring his body back to his house. He was then buried there.

His house later became a large shrine. Many Shia and Sunni leaders helped build and expand it over time. The shrine also holds the tombs of his son, Hasan al-Askari, and his sister, Hakima Khatun. The shrine is a very important place for Shia pilgrims. Sadly, it was badly damaged by bombings in 2006 and 2007.

A Look at His Character

Ali al-Hadi is described as a kind and calm man. He faced the dislike of Caliph al-Mutawakkil for many years with dignity and patience. He was survived by two sons, Ja'far and Hasan. Hasan became the next Imam. His son, Abu Ja'far Muhammad, passed away before him in Samarra.

His Teachings and Writings

Some short religious writings are believed to be by Ali al-Hadi. These include a text about free will. Many Shia sayings about Khums (an Islamic charity, meaning "one-fifth") are linked to Ali al-Hadi and his father. Khums was a way for the Imams to show their leadership in religious and worldly matters. It helped ensure that donations supported the community.

One important saying from Ali al-Hadi, passed down from Ali ibn Abi Talib, explains faith. It says that true faith is in people's hearts, and their actions show it. Surrender to God is what people say with their tongues, which confirms their inner faith.

Another saying from Ali al-Hadi talks about religious scholars. He said that after the hidden Imam appears, scholars will guide people to believe in him. They will defend their religion using proofs from Allah. This will help protect faithful people from misleading ideas. He said that if these scholars were not there, everyone would stray from God's path. He compared scholars to a pilot holding the rudder of a ship, keeping the hearts of Shia Muslims steady. He said these scholars are highly valued by Allah.

See also

In Spanish: Ali al-Hadi para niños

In Spanish: Ali al-Hadi para niños

- Hasan al-Askari

- Naqvis

- Sadaat Amroha

- Jafar ibn Ali al-Hadi

Sources

- "Muḥammad B. ʿAlī Al-Riḍā". Encyclopaedia of Islam (Second). (2022). Brill Reference Online.

- Amir-Moezzi, Mohammad Ali (1994). The Divine Guide in Early Shi'ism : The Sources of Esotericism in Islam. State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780585069722. https://archive.org/details/thedivineguideinearlyshiism1/mode/2up.

- "ʿAlī L-Hādī". Encyclopaedia of Islam (Third). (2022). Brill Reference Online.

- A History of Shi'i Islam. I.B. Tauris. 2013. ISBN 9780755608669. https://archive.org/details/shii-heritage-series-farhad-daftary-a-history-of-shii-islam-i.-b.-tauris-2013/mode/2up.

- Tabatabai, Sayyid Mohammad Hosayn (1975). [Ali al-Hadi at Google Books Shi'ite Islam]. Translated by Sayyid Hossein Nasr. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-87395-390-8. Ali al-Hadi at Google Books.

- Donaldson, Dwight M. (1933). [Ali al-Hadi at Google Books The Shi'ite Religion: A History of Islam in Persia and Iraḳ]. AMS Press. Ali al-Hadi at Google Books.

- Holt, P.M.; Lambton, Ann K.S.; Lewis, Bernard, eds. (1970). The Cambridge history of Islam. 1. Cambridge University Press. https://archive.org/details/cambridgehistory0001unse_v9h2/mode/2up.

- Divine Guide in Early Shi'ism: The Sources of Esotericism in Islam. SUNY Press. 2016. ISBN 9780791494790.

- No God But God: The Origins, Evolution and Future of Islam. Random House. 2008. ISBN 9781407009285. https://archive.org/details/nogodbutgodorigi0000asla_n9k1/mode/2up.

- "'ALI AL-HADI". Encyclopedia of Islamic Civilisation and Religion. (2008). Routledge. 43.

- An Introduction to Shi'i Islam. Yale University Press. 1985. ISBN 9780300034998.

- Religious Authority and Political Thought in Twelver Shi'ism: From Ali to Post-Khomeini. Routledge. 2013. ISBN 978-0-415-62440-4. https://archive.org/details/religiousauthori0000mava/mode/2up.

- Historical Dictionary of Islam (Third ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. 2017. ISBN 9781442277236.

- Esposito, John L., ed. (2004). The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199757268. https://archive.org/details/oxforddictionary00bada/mode/2up.

- "TEWLVER SHI'ISM". Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God. (2014). ABC-CLIO. 644–651.

- "Ḥasan Al-ʿAskarī". Encyclopaedia of Islam (Second). (2022). Brill Reference Online.

- "SAMARRA". Medieval Islamic Civilization An Encyclopedia 1. (2006). Routledge. 694–697.

|

Ali al-Hadi

Born: 15th Dhu al-Hijjah 212 AH ≈ 5th 827–830 CE Died: 3rd Rajab 254 AH ≈ 27th 868 CEof the Ahl al-Bayt |

||

| Shī‘a Islam titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Muhammad al-Taqi |

10th Imam of Twelver Shia Islam 835–868 |

Succeeded by Hasan al-Askari |

| Succeeded by Muhammad ibn Ali al-Hadi Muhammadite Shia successor |

||