American logistics in the Western Allied invasion of Germany facts for kids

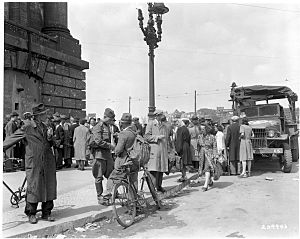

The US Navy ferries troops across the Rhine at Oberwesel.

During World War II, from January to May 1945, American and French forces invaded Germany. This article explains how the American military kept its troops supplied with everything they needed, from food and fuel to tanks and ammunition, during this important final push in Europe.

By early 1945, the American supply system had recovered from the tough battles like the Battle of the Bulge. Even though many supplies were lost and soldiers were injured, new equipment and about 49,000 men from support roles were sent to the front lines. The Allied forces then faced a big challenge: crossing the Rhine River, a wide and fast-flowing barrier. Engineers built bridges and laid railway tracks and pipelines across it. Most supplies traveled by train, with five railway bridges over the Rhine helping the final advance into Germany.

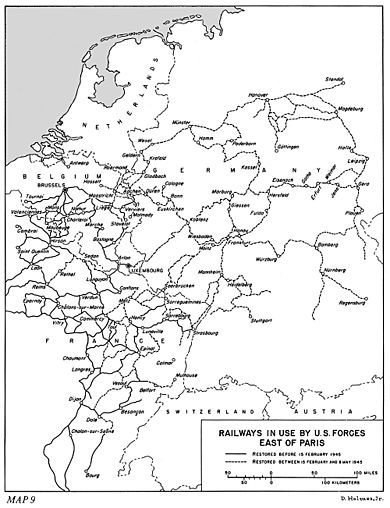

Once across the Rhine, fewer tanks and vehicles were lost in battle, and less ammunition was used. However, fuel and spare parts became harder to find as the armies moved quickly. The American supply system was stretched but didn't break. Train lines were extended closer to the front, with twenty-six engineer regiments working on the railways. By the end of the war in Europe on May 8, trains reached cities like Stendal, Magdeburg, Leipzig, Regensburg and Stuttgart. Trucks also played a big part, with an express service called XYZ moving supplies from train stations to the front. Airplanes also delivered a lot of gasoline in the last weeks of the war.

Contents

Why Supplies Were So Important

The invasion of Northwest Europe began on D-Day, June 6, 1944. At first, American forces got supplies mainly from beaches and the port of Cherbourg. The fighting was tough, and progress was slow until July 25, when a breakthrough allowed a much faster advance. By early September, Allied forces reached the borders of the Netherlands and Germany. But this quick advance stopped because of problems getting enough fuel and supplies, and because German resistance grew stronger.

Between September and November, American forces struggled with unloading ships and moving supplies inland. Things got easier when the important port of Antwerp in Belgium opened in November. Then, in December 1944 and January 1945, the Germans launched big attacks in the Battle of the Bulge and Alsace, which caused more supply problems.

After these German attacks were stopped, the Allied commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, focused on crossing the Rhine. He decided the main effort would be in the north because it had the best crossing spots and led to flat land perfect for fast-moving warfare. This plan also involved British and Canadian forces.

How Supplies Were Organized

In January 1945, there were five American armies in Northwest Europe. The First and Ninth Armies worked with the British. Even when under British command, their supplies were still managed by the American 12th Army Group. This group also included the Fifteenth Army, which guarded areas west of the Rhine, and General George S. Patton Jr.'s Third Army. In the south, the 6th Army Group included the Seventh Army and the French First Army.

The main group in charge of supplies for American forces was the Communications Zone (COMZ), led by Lieutenant General John C. H. Lee. COMZ also served as the main American headquarters in Europe for administrative tasks. This sometimes caused disagreements with the armies, who felt COMZ favored its own needs.

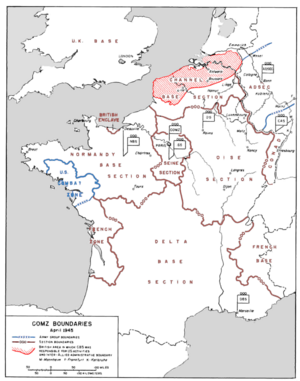

The Advance Section (ADSEC) followed closely behind the armies. Its job was to set up supply routes, take over storage areas from the armies as they moved forward, and work with COMZ and the armies. Forces in Southern France had their own supply route, but by February 1945, it was combined with COMZ to make things simpler.

The supply areas were divided into smaller districts. For example, areas in the UK became districts of the UK Section. This system helped manage the vast amounts of supplies needed across Europe.

Supply Challenges in Early 1945

How Battles Affected Supplies

The opening of the port of Antwerp in November 1944 helped solve many transportation problems. Large supply depots were set up near Liège, Belgium, for the First and Ninth Armies, and near Verdun, France, for the Third Army. Liège was chosen because it was easy to reach by train and river. It had huge storage for food and fuel. Verdun also had many depots for fuel and cold storage for food.

However, the German attack in the Ardennes disrupted these plans. Supplies to Liège had to stop, and unloading ships at Antwerp slowed down. Germans also cut off a main rail link, forcing new routes to be found. Some American engineer units and truck drivers found themselves cut off and had to fight as infantry.

Supplies from threatened depots were moved back to safer COMZ areas by train. This meant trains that should have been bringing new supplies forward were instead evacuating old ones. At Liège, a lot of aviation gasoline was moved out. The Third Army lost fuel from air raids, and other attacks caused more losses. The main railway hub near Liège was also damaged, causing a bottleneck.

To ease port congestion, COMZ tried to get more storage space near Antwerp. The British initially resisted but eventually allowed American depots to be set up in France, near Lille and Charleroi.

Replacing Lost Equipment

The fighting led to a huge demand for things like barbed wire, land mines, small arms ammunition, and anti-tank rockets. Half a million land mines were sent forward. The First Army alone used a lot of anti-tank mines and explosives in December and January to build defenses. All available machine gun ammunition was sent, but it still wasn't enough. Ships with anti-tank rockets and ammunition were rushed to port and unloaded quickly.

Ammunition use skyrocketed. For example, the First Army used 69 rounds per gun per day for its 105 mm howitzers in December, much higher than before. Theater-wide, stocks of 105 mm shells dropped very low. To help, the 12th Army Group borrowed 100 British 25-pounder guns and 300,000 rounds of ammunition.

The American forces lost nearly 400 tanks in December. Other allies loaned tanks, and the British provided 351 M4 Sherman tanks. It was decided that all new American tank production would go to US forces until they had a reserve of 2,000 tanks. By mid-January, all combat vehicles destroyed in battle were replaced. By April, the number of Shermans reached the authorized level of 7,779.

New M26 Pershing tanks also started arriving in January 1945. By V-E Day (Victory in Europe Day), there were 310 Pershing tanks in Europe, with about 200 issued to troops. Losses of other weapons like Browning Automatic Rifles and mortars were also replaced by mid-January. By February 21, despite ongoing fighting, army depots held large amounts of ammunition.

Moving Supplies Forward

By early February, more ships were being unloaded at ports than were waiting, making the process much more efficient. This reduced the time it took for trucks and trains to deliver cargo.

In February, the First Army moved supplies back across the Meuse River to their original locations and set up a new fuel station in Stolberg, Germany. ADSEC's ability to deliver supplies directly to units by rail eased the burden on trucks, allowing them to build up reserves of food, fuel, and ammunition.

A fast express shipping service called REX was started in January for high-priority combat cargo. By May 8, about 120,000 tons had been shipped this way, mostly weapons and communication gear. A daily express train service, the "Toot Sweet Express," also began in January, carrying urgent freight from the United States to forward depots. This also helped reduce theft of packages.

Challenges with Soldiers

Having Enough Troops

By May 1944, plans for the US Army had been reduced to 89 divisions. The Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall, felt that 90 divisions were the most that could be supported. The number of soldiers in combat roles steadily dropped because more support troops were needed. By December 1944, the European theater had 52 divisions and 1,392,100 support troops. The plan was to increase the number of divisions to 61.

It was hard to predict exactly what units would be needed. This meant some units were used for tasks they weren't trained for, and some had to be changed or broken up to provide soldiers for more urgent needs. The rapid advance across France in 1944 used up many extra soldiers to keep truck companies running non-stop. More military police battalions were also needed to handle the large number of German prisoners of war.

Support also had to be given to the French First Army, which didn't have enough supply units. In December 1944, the Southern Line of Communications (SOLOC) had 106,464 support troops, including French and American soldiers, to support 17 divisions. Four more American divisions were added to the 6th Army Group in December, and more French divisions were planned. Additional combat units were transferred for the Colmar Pocket operations in January and February, along with 12,000 more support troops.

To get 123,000 support troops for nine additional divisions, the War Department deactivated anti-aircraft battalions, which were no longer needed. But they hesitated to provide 16,000 more truck drivers unless the theater reduced other units. The field forces were willing to accept fewer combat units to get the support they needed. They agreed to cut ten field artillery battalions in exchange for the truck drivers. This was a tough choice, as these units might be needed if German resistance grew strong.

Replacing Injured Soldiers

Limiting the US Army to 89 divisions meant that units in Europe had to stay on the front lines for long periods. They needed constant replacements to stay at full strength. American soldiers injured in battle in November were much higher than expected. There were also many non-battle injuries, mostly from cold weather conditions like trench foot and frostbite. In 1944–1945, there were over 71,000 cold weather injury cases in American forces. Both battle and non-battle injuries mostly affected infantry soldiers, who made up about 80% of them.

The War Department said it couldn't send enough infantry replacements from the United States. Casualties were even higher in December due to the German Ardennes attack. General Bradley was worried about infantry replacements being sent to the Pacific. He asked, "Don't they realize that we can still lose this war in Europe?"

Soldiers were replaced individually. Replacements often lost their skills while traveling or waiting for assignments. Some found it hard to fit into their new units, as experienced soldiers were wary of getting to know new recruits who might soon become casualties. Some divisions unofficially held back replacements until fighting eased, so new soldiers could adjust more easily.

By 1945, nearly 40% of replacements were "casuals"—men who had already been injured and treated. These men usually wanted to return to their old units, and commanders wanted them back. Unofficially, replacement depots tried to send men back to their old units, but it wasn't always possible. In January 1945, this policy was officially allowed for the 6th and 12th Army Groups. That same month, a new policy started where all replacements, including casuals, formed four-man groups to train, travel, and fight together.

One way to get more infantry replacements was to use infantry soldiers serving in the Communications Zone for guard duties. A program started in December 1944 to give 60% of these soldiers three weeks of refresher training before sending them to the front. Training for soldiers from other branches to become infantry was also shortened.

On December 26, SHAEF asked for volunteers to join the infantry. Among them were 4,562 African American soldiers, many of whom accepted a lower rank to qualify. The Army was still segregated by race, so these men formed 53 infantry platoons. SHAEF announced that all physically fit men in non-combat units could retrain as infantry, except for medics and highly specialized roles. By January 1, 1945, COMZ was ordered to provide 21,000 men over five weeks.

Casualties remained high in January, but by March, the efforts to get more replacements started to work. Casualties were lower than expected, and a surplus of infantry replacements began to build up. By April, there were 50,000 extra infantrymen. Some retrained infantrymen were assigned to military police and anti-aircraft units to guard prisoners of war and displaced persons. The War Department decided to send 19,000 infantry replacements planned for Europe in May to the Pacific instead.

Meanwhile, there was a shortage of 20,000 men in other support roles. The ADSEC commander reported that his units were understaffed. There was little hope of getting more support troops. So, more civilians and prisoners of war were used to fill these roles. About 49,000 men were transferred from COMZ to combat roles between February and April. About half of them finished their retraining before the war in Europe ended on May 8.

Planning for the Rhine Crossing

The Rhine River was the biggest natural barrier the Allies had faced since the English Channel. Planning to cross it began in September 1944. Planners looked at three possible crossing areas in Germany. The Emmerich–Wesel area in the north was preferred. The main challenge for supplies during a river crossing was that the crossing site would become a major bottleneck.

SHAEF estimated that 15 British or Canadian and 21 American divisions could be supported in the northern area. A key decision was to lay pipelines across the river to provide three-quarters of the fuel needed for forces on the east bank. This was risky because of possible sabotage, but fuel made up a third of the armies' supply needs, and pipelines would save a lot of traffic on the bridges. The 12th Army Group expected pipelines to be working three weeks after crossing the river. They didn't expect railways to be ready east of the Rhine for nine weeks.

In September 1944, anticipating reaching the Rhine soon, General Bradley asked the US Navy for help. Four boat units, each with 24 landing craft, vehicle, personnel (LCVP) boats, were formed. These were transported from the UK to France. Later, 45 larger landing craft mechanized (LCM) boats were added.

Moving the LCVPs overland was easy, as they could be carried by trailers. The LCMs were harder because they were too wide for many bridges and roads. Some LCMs traveled by canal, but others had to go overland. They were carried by large tank transporters. Their height had to be reduced, and in some cases, parts of buildings were even removed to let them pass!

The Chief Engineer for the European theater held a meeting in October 1944 to discuss building bridges across the Rhine. A long list of materials was made, including very long steel beams and pilings. Moving these heavy and awkward loads forward required careful planning. ADSEC planned to provide double-track railway lines to support the armies.

To save special M2 treadway bridges, the Ninth Army engineers planned to use narrower M1 treadway bridges for one Rhine crossing. A problem was that Sherman tanks had track extenders for snow and mud. So, two M1 treadway bridges were changed to make more space between the tracks.

General Eisenhower decided that the entire west bank of the Rhine had to be cleared before attempting a crossing. The river would then be a defensive barrier for both sides. There was no plan to capture an intact bridge; in fact, Eisenhower had asked if all bridges could be destroyed. There were 26 major bridges over the Rhine. It was expected that the retreating Germans would blow up all the bridges.

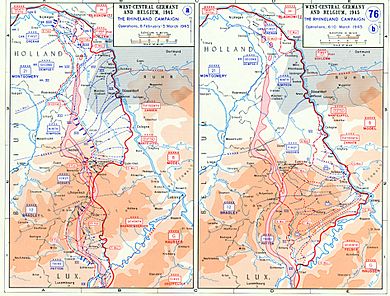

The Rhineland Campaign

After the German attacks in the Ardennes and Alsace were defeated, the Ninth Army received priority for ammunition, as it was to make the main Rhine crossing effort. In February, 45% of artillery ammunition went to the Ninth Army. However, the Third Army was more active in the first weeks of the month and had much less ammunition on hand. The 12th Army Group headquarters had to adjust the supply quotas.

Before reaching the Rhine, the Ninth Army had to cross the Roer River. The Ninth Army's troop movements for this crossing, called Operation Grenade, happened during a thaw and heavy rains. Roads quickly became very bad under the military traffic. Some roads were made one-way to protect them, and engineers worked hard to patch roads and recover broken-down vehicles. A bridge over the Maas River at Maastricht was threatened by floods and had to be closed.

Upriver on the Roer were two large dams still held by the Germans. Their destruction could cause a massive flood for five or six days. The First Army captured the Urft Dam on February 4 and the Rur Dam five days later. The retreating Germans destroyed the discharge valves, creating a controlled flood. The water rose quickly, and the Ninth Army's crossing was postponed until February 23, when the river was expected to return to normal.

This delay allowed more supplies to be moved forward. In one week, over 32,000 tons were delivered by rail. The Ninth Army's truck companies were reinforced to move these supplies. About 30% of the automotive spare parts needed for Operation Grenade came from salvaged equipment. Before the advance to the Rhine, some of the Ninth Army's light tanks and reconnaissance units received new M24 Chaffee light tanks.

The Ninth Army gathered twenty days' worth of ammunition (about 46,000 tons) and ten days' worth of fuel (about 3 million gallons). In case of bridge delays, 500 transport planes were ready to deliver supplies. Most fuel came from a pipeline from Antwerp to tank farms near Maastricht. During the February thaw, the fuel transfer station at Maastricht couldn't handle the traffic, so a new one was set up further forward.

Operation Grenade launched on February 23. By the end of the first day, many bridges were open or almost finished. Railway bridges over the Roer in Germany were rebuilt and opened for traffic on March 11. The railway lines were extended towards Cologne and Wesel.

Crossing the Rhine River

First Army's Crossing

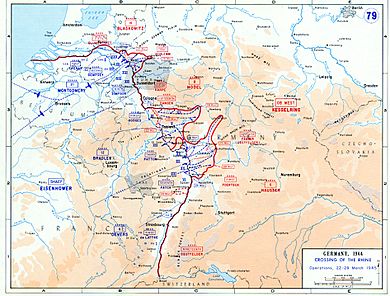

Even though the plan was to destroy bridges, efforts were made to capture one intact. On March 2, a task force from the Ninth Army tried to capture the bridge at Oberkassel, Germany, but it was blown up before they could secure it. By March 5, all eight bridges in the Ninth Army's area had been destroyed. However, on March 7, 1945, the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen, Germany, was captured intact by the First Army's 9th Armored Division. The German demolition charges failed to destroy it completely. Eisenhower and Bradley quickly decided to use this unexpected chance.

Engineers quickly set up ferries, and special amphibious trucks called DUKWs were also used. Nearly 8,000 men crossed the Rhine in the first 24 hours after the bridge was captured. Navy boat units launched LCVPs on March 11, creating a ferry service. These boats could carry infantrymen across the river faster than they could walk across the bridge. By March 27, they had ferried 14,000 troops and 400 vehicles.

The German air force tried to destroy the bridge but faced heavy anti-aircraft fire. The First Army used thirteen anti-aircraft battalions to defend the bridge, claiming 109 enemy aircraft destroyed. The Germans also tried to destroy it with artillery and even V-2 rockets. A treadway bridge was opened on March 10, allowing 3,105 troops to cross in two days. Construction of a heavy pontoon bridge began on March 10, and it opened on March 11, carrying eastbound traffic.

The Ludendorff bridge was closed for repairs on March 12. Sadly, on March 17, it suddenly collapsed, weakened by the initial demolition attempt and vibrations from artillery fire. Twenty-eight men were killed. The next day, work began on a 1,258-foot floating Bailey bridge, which opened on March 20. Another two-way Bailey bridge was built at Bad Godesberg, Germany, and opened on April 5.

After the capture of the Ludendorff bridge, ADSEC began rebuilding the railway line to Remagen. When the bridge collapsed, the railway line was extended south to Koblenz along the west bank of the Rhine. SHAEF decided that advancing on the Ruhr from the Remagen bridgehead was not good for logistics because of the difficult terrain. Instead, they called for an advance to the south, where the bridgehead could connect with railways and pipelines from Verdun.

Ninth Army's Crossing

The Ninth Army's 30th and 79th Infantry Divisions began crossing the Rhine south of Wesel at 2:00 AM on March 24, supported by a huge artillery barrage. The assault divisions quickly crossed, followed by amphibious vehicles carrying supplies and ammunition. Navy boat units then ferried thousands of troops, tanks, bulldozers, and jeeps across. Tracer ammunition and flashlights were used to guide the boats in the dark.

Light German resistance allowed tactical floating bridges to be built faster than expected. Construction of the first bridge, a 1,530-foot treadway bridge, began at 6:30 AM on March 24 and was finished in just nine hours. Over the next week, three more treadway bridges, three heavy pontoon bridges, and three floating Bailey bridges were completed.

Although the Rhine was now crossed at several points, Wesel was the only chosen crossing point securely in Allied hands on March 26. Engineers decided to start building a railway bridge there. They chose an upstream site near a demolished road bridge where the Germans had laid a single-track railway line. This meant they also had to bridge the Lippe River.

Work began on March 29 and was completed in ten days, a huge achievement. The bridge opened to traffic at 1:00 AM on April 9 and was named after Major Robert A. Gouldin, an engineer who drowned during construction. The bridge had double-track approaches on both sides, and the first train crossed 25 minutes after it opened.

Nearby, the Ninth Army's engineers built a three-lane highway bridge, also bridging both the Rhine and the Lippe. A lot of fill material was needed for the approach roads, and a fort was demolished to provide rubble. This bridge opened on April 18 and was named the Roosevelt bridge in honor of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had died the week before.

Third Army's Crossing

In the south, the Third Army received supplies by road and rail from depots near Verdun and Reims. A rail link to Trier, France, opened on March 18. Trucks then hauled supplies between Trier and the Third Army depots. The quick collapse of German resistance allowed railways to be extended to the Rhine, though not in time for the initial assault crossings. A single-track line to Mainz, Germany, was completed by April 1.

The Third Army had planned for the Rhine crossing since August 1944 and started collecting equipment the next month. When army boundaries were adjusted, General Patton made sure the supply dumps stayed in his zone. Although stocks were used up during earlier river crossings, the dumps still held many assault boats, storm boats, outboard motors, and sections of floating Bailey, heavy pontoon, and treadway bridges. These supplies were brought forward by trucks, carefully prioritized.

At 10:00 PM on March 22, the Third Army's 5th Infantry Division began crossing the Rhine at Nierstein and Oppenheim, Germany. This site was chosen because it was on a main road to Frankfurt, and the Rhine was narrower and slower there. For political reasons, American leaders wanted an American assault crossing before the British one the next day. It was presented as an improvised crossing, but only the date was changed.

This change caused some problems. A German howitzer disrupted efforts to assemble rafts. It took until 8:30 AM for rafts to be ready so tank destroyers could cross and silence the German gun. Navy boat units were on the water by 6:30 AM on March 23. Work on a treadway bridge began at daybreak and opened at 6:00 PM on March 23. A heavy pontoon bridge was ready by noon the next day, and a second treadway bridge was completed on March 25.

Patton's chief artillery officer suggested using small observation aircraft to move troops across the Rhine. A test showed that 100 light aircraft could transport a battalion in two hours, but the appearance of German planes over the crossing site made them abandon the idea.

The 87th Infantry Division tried to cross the Rhine Gorge at Rhens and Boppard, Germany, on March 25. This was a very difficult part of the river with steep cliffs. Patton chose it believing it would be lightly defended, but he was wrong. German defense at Rhens was so strong that the crossing was moved to Boppard. A treadway bridge began construction there on March 25 and was completed the next day.

The 89th Infantry Division attempted a crossing of the Rhine Gorge at St. Goar and Oberwesel, Germany, on March 26. Defenders at St. Goar were ready and well-armed. The main crossing effort shifted to Oberwesel, where resistance was also strong. A treadway bridge at St. Goar took 36 hours to build due to the swift current and rocky bottom. Meanwhile, units of the 89th Infantry Division crossed using the 87th Infantry Division's bridge at Boppard.

Patton could have used the bridges at Oppenheim and Boppard, but they were not in good locations for supplies, with limited road and rail access. So, he chose a third crossing at Mainz, which was more central and had good road and rail networks. The 80th Infantry Division began crossing there at 1:00 AM on March 28. Engineers built a 1,896-foot M2 treadway bridge, believed to be the longest of its type built under combat conditions. ADSEC also built a new railway bridge at Mainz, which was 2,215 feet long and took nine and a half days to build. Patton opened it on April 14, naming it after President Roosevelt.

Seventh Army's Crossing

The Seventh Army crossed the Rhine upstream from Worms, Germany, at 2:30 AM on March 26. Engineers built a treadway bridge, but it wasn't open until 6:50 PM. In the meantime, another battalion built a 1,047-foot heavy pontoon bridge, named the Alexander Patch Bridge after the Seventh Army's commander. Over 3,000 vehicles crossed this bridge on its first day. Another bridge was built downstream but saw little use because the Alexander Patch Bridge was better located. Two heavy pontoon battalions then teamed up to build a new heavy pontoon bridge at Ludwigshafen, Germany, on March 30, which opened to heavy vehicles that evening and was named the Gar Davidson Bridge.

The 1st Military Railway Service built two railway bridges over the Rhine in the Seventh Army's area. The first, a 937-foot bridge at Mannheim, was completed on April 23. The second, an 851-foot bridge at Karlsruhe, Germany, was completed on April 29. With the bridges at Wesel and Mainz, this made four railway bridges over the Rhine. A fifth railway bridge was built at Duisburg, Germany, starting on May 2. This 2,815-foot bridge was completed in a record six and a half days but was too late to impact the campaign.

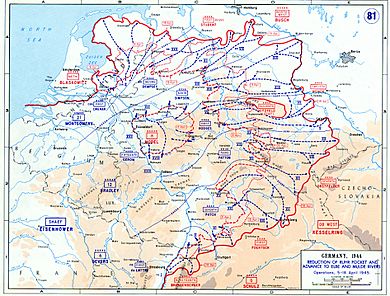

The Final Push into Germany

Once the Rhine was crossed, American armies advanced quickly into Germany. A major goal was to encircle the Ruhr industrial area, which happened when the First and Ninth Armies met at Lippstadt on April 1. The armies then moved east and south. German resistance often crumbled, but remained fierce in some areas like the Thuringian Forest. By April 18, the Ruhr pocket was eliminated, and the armies reached the Elbe and Mulde rivers. The Third and Seventh Armies then drove south into Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia, while the First Army met the Red Army at Torgau on April 25.

Changes in Organization

For the final advance, ADSEC and CONAD were planned to follow the 12th and 6th Army Groups, but without specific area responsibilities in Germany. ADSEC moved its headquarters to Germany, first to Bonn, then to Fulda. CONAD set up its headquarters in Kaiserslautern, Germany.

Railways in Action

Logistics plans didn't expect much railway traffic beyond the Rhine until mid-April. However, engineers immediately began repairing the railway network. Some railways were used even before the bridges opened, hauling supplies brought across the river by truck. In the north, the line from Münster to Paderborn to Kassel was already in use when the Wesel bridge opened on April 9, allowing the Ninth Army to get supplies by rail.

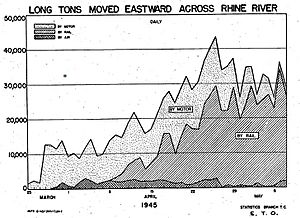

Within ten days of the Wesel bridge opening, 20,000 tons of supplies were carried across the bridges daily. The Mainz and Wesel bridges together were estimated to handle 20,000 tons per day, but they often moved more. Between May 2 and 4, railways carried 80% of the 35,000 tons of equipment and supplies moved across the Rhine.

The Wesel bridge became a major bottleneck after the Ludendorff bridge collapsed because it had to handle traffic for both the First and Ninth Armies. The British also asked for bridge traffic, which was eventually allowed. This led to the authorization of an additional bridge at Duisburg.

A shortage of railway cars developed at the Mainz crossing, where too many loaded cars were waiting to be unloaded. To fix this, returning cars loaded with captured German materials were unloaded. Improvised storage areas were set up for these materials. Part of the problem was that the Third Army tried to rush the most urgent supplies, which caused less urgent cargo to be sidetracked.

Over the next few weeks, the railway network was repaired as fast as the armies advanced. Twenty-six engineer regiments worked on the railways. The railway service supporting the Third Army reached Würzburg on April 24 and Nurnberg on May 5. By May 8, train stations were set up in many German cities. By July 1945, the Military Railway Service had received nearly 2,000 locomotives and over 43,000 railway cars, and was operating 11,000 miles of track.

Truck Transport

The Motor Transport Service

The Motor Transport Service (MTS) was formed in October 1944 to manage military trucks. By January 1945, it had 55 officers and 128 enlisted personnel. The MTS focused on preventing breakdowns and improved the number of working vehicles per company. They also got more tires and tubes.

Of the 198 truck companies in January 1945, 104 used standard 2½-ton trucks. Many semi-trailers and truck-tractors were unloaded in Marseille, France, and thirty truck companies were sent there to learn how to use them. In the first three months of 1945, the MTS received 64 new companies. Fourteen companies came from the Persian Gulf Command and were very experienced with these vehicles.

During the Rhineland operations, trucks moved huge amounts of supplies. From February 11 to 23, 1945, trucks moved over 1 million tons of supplies and 377,000 people. This increased even more from February 24 to March 11.

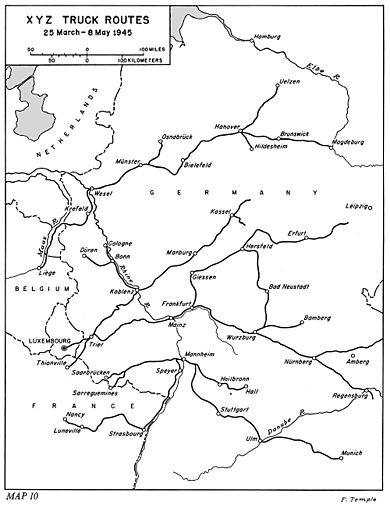

It was expected that widespread destruction would make it hard for railways to support operations beyond the Rhine, so trucks would have to take over. MTS planned another express route, similar to the Red Ball Express of 1944, called XYZ. This plan had three phases to meet different supply needs, aiming to move 8,000 to 10,000 tons per day. The four XYZ routes started from Liège, Düren, Luxembourg City, and Nancy, France. Having separate routes helped reduce traffic jams.

The XYZ Program

The XYZ program started on March 25 and lasted until May 31. To control operations, the MTS organized provisional highway transport divisions to support the different armies. As the armies spread out, it became harder for one division to support two armies, so more divisions were organized.

Although not as famous as the Red Ball Express, XYZ was much more successful. It had better planning, organization, and coordination. The drivers were more experienced, and there were more heavy trucks available. While some hauls were over 200 miles, the average was closer to 140 miles, which was shorter than the Red Ball Express routes and allowed drivers more rest. This was partly because train stations moved forward quickly, and 17,000 people worked on road maintenance. "GI Joe Dinners" were set up every 50 miles where drivers could get hot meals.

XYZ still had challenges. The biggest was keeping the trucks running. Mechanics traveled with convoys, and trucks got four hours of maintenance before setting out. Replacement vehicles and spare parts were slow to arrive. On one route, a thousand captured German tires helped with shortages. Fuel tankers often leaked on winding mountain roads, and many needed repairs. Destinations changed frequently as armies advanced, and bridges often caused bottlenecks.

The Third Army needed about 7,500 tons of supplies daily, including 2,000 tons of fuel. To meet this, its highway transport division had 62 truck companies. By the end of May, it had hauled over 354,000 tons of supplies, nearly 30 million gallons of fuel, and 381,000 people. The Ninth Army's division delivered over 122,000 tons, and the First Army's division delivered over 182,000 tons. Over the 63 days XYZ was active, over 871,000 tons of supplies were delivered, averaging over 12,800 tons daily.

As trucks were used for XYZ, there was a risk of slowing down port operations. On April 5, COMZ asked for some May convoys to be delayed, which would save ports from handling 60,000 tons of cargo.

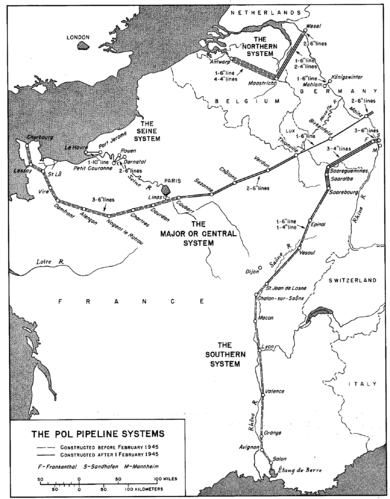

Fuel Pipelines

By February 1945, COMZ had huge stocks of fuel, much more than needed for sixty days. Fuel was being unloaded at a rate of 13,000 tons per day through various ports. At this point, the northern pipeline system from Antwerp ended at Maastricht. This changed on March 3, when work began to extend the pipeline to Wesel. This project faced many difficulties, including deep mud, a shortage of couplings (forcing engineers to weld pipes), mined areas, and floods. Despite these, the extension was completed and working by March 28. The main pipeline system from Cherbourg reached Châlons-sur-Marne, France, in February, and Thionville in March. The southern system from Marseille was extended to Sarralbe.

Pipelines were also laid across the Rhine River separately from the main systems. Gasoline would be delivered by train to the east bank and then pumped across the Rhine, reducing truck traffic over the bridges. The first pipeline across the Rhine was laid near Remagen, starting on March 25 and working three days later. It was extended to an autobahn where storage tanks were set up.

In the Third Army's area, a pipeline was laid across a wrecked railway bridge at Mainz. This was working by April 8 and connected to the main system on April 22. The bridge was found unsafe, so two new pipelines were run across the railway bridge. The Seventh Army ran a pipeline across the Rhine over a Bailey bridge at Frankenthal, Germany, to a pipehead on the east bank. Work started on April 7 and finished on April 15. Two more lines were added later, one running along the riverbed. The first 4-inch pipeline of the southern system reached Frankenthal on April 20. At Wesel, pipeline work began on March 21 and finished on April 3.

Fuel use soared in April as the armies moved forward, sometimes exceeding 1 million gallons in a single day. In late April, deliveries started falling short of demand, and the Third and Seventh Armies' reserves dropped to less than two days. The Third Army had to ration fuel, but fuel shortages did not significantly impact operations.

Air Supply

After SHAEF allowed air transport to support the armies after the Rhine crossing, the Third Army requested 2,000 tons of supplies on March 27. Bad weather prevented this immediately, but 329 aircraft delivered 197,400 gallons of gasoline on March 30. Air supply became very important in April, peaking in the second week when over 6,200 flights delivered 15,000 tons to forward airfields. Engineers quickly repaired airfields as soon as they were captured so they could be used for air supply.

The Third Army had the longest supply lines and used air supply the most. Between March 30 and May 8, it received about 27,000 tons of supplies by air, which was more than half of all air supply tonnage. Of this, 27,000 tons (about 6 million gallons) was gasoline, making up 22% of the Third Army's gasoline receipts during that time. It also received an average of 50,000 rations daily by air, and sometimes critical items like batteries and spare tires. In April, the IX Troop Carrier Command averaged 650 flights each day, delivering 1,600 tons daily. In the same month, it also evacuated about 40,000 injured soldiers and 135,000 Allied military personnel freed from prisoner of war camps in Germany.

After Germany Surrendered

Moving Troops and Supplies

In October 1944, the War Department started a policy where supply requests were marked "STO" (stop) if they would be canceled when the war ended, or "SHP" (ship) if they would continue. By April, requests for weapons, engineer, medical, and signal supplies were much higher than what was being used. But it wasn't until May 5 that ETOUSA asked for STO shipments to be canceled, which involved 1.28 million tons of supplies. STO cargo at the New York Port of Embarkation was sent back to depots. If STO cargo was already loaded on ships, it was allowed to be shipped. Seventy-five ships were sent back unloaded or reloaded with STO cargo.

When the war in Europe ended on May 8, there were 5.5 million tons of supplies on the continent, including 700,000 tons of ammunition. The war didn't end for the United States, as it was still fighting Japan. Units moving to the Pacific took their equipment with them. Everything else had to be repaired, packed, and shipped to the Pacific or the United States, or gotten rid of. Plans included repairing millions of clothing items, motor vehicles, radios, and construction equipment.

Planning to move forces to the Pacific began in November 1944. About 395,900 troops were to be shipped directly from Europe to the Pacific, while another 408,200 would go via the United States. Another 2.18 million soldiers were to be released from service based on a points system. This redeployment began on May 12, 1945. Marseille was the main port for direct shipments to the Pacific, and Le Havre, Antwerp, and Liverpool, England, for shipments to the United States. Soldiers were mainly shipped through Le Havre, where five staging areas were set up. Direct shipments to the Pacific ended suddenly in August when Japan surrendered.

To house the soldiers being released from service, COMZ activated the Assembly Area Command on April 9, 1945. This command built seventeen transit camps around Reims to hold up to 270,000 soldiers waiting to return to the United States. This involved building 5,000 huts, setting up 33,000 tents, and laying 8 million square feet of concrete. By the end of 1945, the Assembly Area Command had processed 600,000 troops. The movement of units ended on February 26, 1946.

On May 12, 1945, an order officially separated the headquarters of ETOUSA and COMZ. This took effect on July 1, when ETOUSA became United States Forces European Theater. On August 1, COMZ became Theater Service Forces, European Theater. A new command was created to operate the port of Bremen, Germany, and manage the surrounding area, which was an American area within the British occupation zone.

Prisoners of War

When the fighting ended, COMZ was feeding 3,675,000 troops and 1,560,000 prisoners of war (POWs). The Third Geneva Convention of 1929 required the US Army to feed and care for POWs. This was partly avoided by a declaration from Eisenhower that this only applied to those who surrendered before May 8, 1945. Those who surrendered after this date were called "disarmed enemy forces" (DEFs) instead. DEFs did not receive the same treatment as POWs. In theory, German civil authorities were responsible for feeding DEFs. DEFs received the same ration as civilians, which could be as low as 500 calories per day in some places.

In contrast, US soldiers had a diet of 3,500 calories per day. It was planned that US occupation forces would be fed by Germany, but because food was scarce in post-war Europe, the US actually shipped millions of tons of relief supplies to Germany. Many POWs and DEFs found jobs supporting the US Army. By September 30, 1945, the US Army in Germany employed over 575,000 POWs and DEFs in German service units. They helped with cutting trees, loading trucks, baking bread, and maintaining vehicles.

What Was Learned

Once the Rhine was crossed, the loss of tanks, vehicles, and equipment, and the use of ammunition, went down. However, fuel and spare parts became harder to find, which is normal in fast-moving operations. The American supply system was stretched, but it didn't break. Historian Charles B. MacDonald, who was a company commander in the war, wrote that the success was due to a "sound logistical apparatus expertly administered." It's clear that the American forces won the war, and as historian Roland Ruppenthal wrote, "few armies in history have been as bountifully provided for."

There was still a feeling that the American supply system could have been more efficient. The biggest problem was the command structure, with ETOUSA-COMZ being the official theater staff, but many general headquarters tasks being handled by SHAEF. The European theater also had shortages of manpower, and finding the right balance between combat and support units was difficult. The supply system, with its ports, depots, railways, highways, pipelines, and hospitals, was very complex, and managing something so complicated naturally involved some inefficiencies.

See Also

Images for kids