Atlanta in the American Civil War facts for kids

The city of Atlanta, Georgia, in Fulton County, was a very important railroad and business hub during the American Civil War. Even though it wasn't a huge city, Atlanta became a key target in 1864 when a strong Union Army marched from Tennessee. When Atlanta fell, it was a major turning point in the war. It gave the North more hope and helped President Abraham Lincoln get re-elected. This also led to the end of the Confederacy. Taking control of Atlanta, often called the "Gate City of the South," was especially important for Lincoln because he was running for re-election against George B. McClellan.

Contents

Atlanta's Early War Years

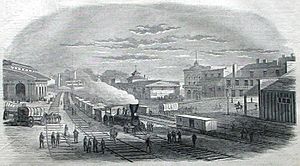

Atlanta started as a railroad stop called Terminus in 1837. It grew quickly as more railroads were built. By 1860, Atlanta was still a small city in the United States, but it was the 13th largest in the Confederate States of America. Many factories and workshops were built there, making the city's population grow to nearly 22,000 people.

Atlanta was a vital center for moving goods and supplies. Several major railroads met there:

- The Western and Atlantic Railroad connected Atlanta to Chattanooga, Tennessee.

- The Georgia Railway went east to Augusta.

- The Macon & Western linked Atlanta to Macon and Savannah in the south.

- The Atlanta and West Point Railroad connected Atlanta to West Point, Georgia, and then to Montgomery, Alabama.

Because it was thought to be safe early in the war, Atlanta became a major storage area for the Confederacy. Warehouses were filled with food, supplies, ammunition, and clothing for the Confederate armies.

Many factories in Atlanta helped the Confederate war effort:

- The Atlanta Rolling Mill made metal plates for armored ships called ironclads.

- The Confederate Pistol Factory made pistols.

- The Novelty Iron Works produced military supplies.

- The Confederate Arsenal made weapons.

- The Atlanta Machine Works produced cannons.

- The Naval Ordnance Works made gun carriages and shells for the Confederate navy.

Atlanta also had several hospitals to care for wounded soldiers. These included the General Hospital, the Distribution Hospital, and even the Atlanta Medical College.

By July 1864, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston ordered that all hospitals and factories in Atlanta be emptied. Important machinery and supplies were sent to other cities like Augusta and Columbia.

Several newspapers were published in Atlanta during the war, such as the Atlanta Southern Confederacy and the Daily Intelligencer. Some even moved to Macon, Georgia, when Union forces took over.

Atlanta Becomes a Target

After the fall of Vicksburg in 1863, Confederate leaders worried that Atlanta would be the next target for the Union Army. Jeremy F. Gilmer, the Chief Engineer for the Confederacy, asked Captain Lemuel P. Grant to plan defenses for Atlanta.

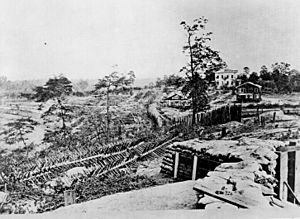

Captain Grant designed a circle of forts and trenches around the city, about 10 to 12 miles long. These defenses would have strong forts for cannons, connected by trenches for infantry. They also included obstacles like felled trees to slow down enemy attacks. The goal was to keep the Union army far enough away so they couldn't easily shell the city.

Construction on these defenses began in August 1863. By late October, 13 of the 17 planned forts were finished. These defenses needed about 55,000 troops to be fully manned.

In 1864, as feared, Atlanta became the main target of a major Union invasion. The area around Atlanta saw several fierce battles, including the Battle of Peachtree Creek, the Battle of Atlanta, Battle of Ezra Church, and the Battle of Jonesboro. On September 1, 1864, Confederate General John Bell Hood left Atlanta after a five-week siege by Union General William Sherman. Hood ordered all public buildings and military supplies to be destroyed.

Siege of Atlanta (July–August 1864)

In the spring of 1864, the Confederate Army of Tennessee, led by General Joseph E. Johnston, was dug in near Dalton, Georgia. In May, Union forces under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman began their Atlanta Campaign. By early July, the Confederates had been pushed back to the edge of Atlanta. Both armies used the Western & Atlantic Railroad to get their supplies.

The last natural barrier between the Union forces and Atlanta was the Chattahoochee River. By July 9, Union forces had secured three crossings over the river. They rested and prepared for their advance on Atlanta, which began on July 16.

Union cavalry forces cut the rail lines connecting Atlanta to Montgomery, Alabama, and Augusta, Georgia. This made it harder for the Confederates to get supplies.

On July 18, 1864, General Joseph E. Johnston was replaced by General John Bell Hood as commander of the Confederate forces.

General Sherman ordered his army to move on Atlanta on July 20. He told his commanders to fight if they found a good opportunity. If they reached the city without being fired upon, they should stop and wait. But if they were fired upon from the city's forts or buildings, they should return fire without hesitation, even if families were present.

General Hood attacked the Union forces at Peachtree Creek on July 20, but the Confederates were pushed back. They attacked again on July 22, east of Atlanta, but were again defeated with heavy losses at the Battle of Atlanta. During this battle, Union General James B. McPherson and Confederate General William H. T. Walker were killed. Sherman had now cut two of the four rail lines into Atlanta.

Sherman then tried to cut the remaining supply lines west of Atlanta. Hood sent troops to protect them. The Union forces dug in near Ezra Church, and the Confederates attacked on July 28. They were repulsed at the Battle of Ezra Church. Even though the Union won, they failed to cut the rail line.

The Union forces continued to move south, and the Confederates extended their lines to match. They clashed again at Utoy Creek on August 4-7, but the Union forces were pushed back and failed to break the Atlanta and West Point Railroad.

Union artillery began shelling downtown Atlanta on July 20, 1864. Captain Francis De Gress reported firing the first shells into the city. The shelling continued until August 25. Four large siege cannons were brought in and fired over 4,500 rounds at Atlanta. General Sherman reported that he threw about 3,000 shells into Atlanta on one day.

There are no official records of how many people were killed by the shelling. Union cavalry tried to cut the remaining rail lines, but the damage wasn't enough to stop the Confederates from repairing them. There was constant fighting between the lines, causing casualties on both sides.

On August 25, Union forces pulled back from their positions around Atlanta. They marched south to attack the Macon & Western Railroad. On August 31 – September 1, the Confederates again failed to stop the Union troops at the Battle of Jonesboro.

Fall of Atlanta (September 1–2, 1864)

With all his supply lines cut, General Hood decided to abandon Atlanta. On the night of September 1, his troops marched out of the city. Hood ordered 81 rail cars full of ammunition and other military supplies to be destroyed. The huge fires and explosions were heard for miles around.

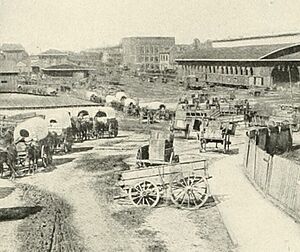

On September 2, Union Major General Slocum sent scouts toward Atlanta. Mayor James M. Calhoun and other important citizens rode out under a flag of truce to surrender the city to the Union Army. Colonel John Coburn accepted the surrender. When General Slocum heard that the Confederates had left, he moved seven brigades to occupy Atlanta.

Occupation of Atlanta (September 3 – November 16, 1864)

On September 3, General Sherman learned that the Confederates had left Atlanta. He immediately ordered Slocum to take control of the city and to tell all civilians that they would have to leave.

Sherman decided not to chase General Hood's Confederate forces. Instead, he ordered his armies to set up camp around Atlanta. General Sherman made his headquarters in the home of John Neal. Other Union generals also used private homes in the city.

Union forces occupied Atlanta until November 15-16, when they began their "March to the Sea." During these 73 days, Sherman's troops watched Hood's army, evacuated civilians, built shelters and defenses, and gathered food. Finally, they destroyed everything in Atlanta that could be useful for the war.

Evacuating Civilians (September 8–21, 1864)

On September 5, the military police in Atlanta ordered all families whose male relatives were fighting for the Confederacy or had gone south to leave the city within five days. They were allowed to take clothes, some furniture, and a small amount of food. General Sherman told General Hood about his plan to evacuate all civilians, which led to angry letters between the two generals. Mayor Calhoun also asked Sherman to change his mind, but Sherman refused.

On September 8, 1864, General Sherman issued a special order stating that Atlanta was needed only for military purposes and that everyone except the U.S. Army must leave. The order also said that soldiers could use materials from buildings like barns and sheds to build their own shelters.

Mayor James M. Calhoun told citizens they had to leave. They had to register how many adults, children, and servants were in their families, and how many packages they were taking. Between September 10 and 20, over 1,600 people registered to leave, taking thousands of packages with them.

Building New Defenses (October 3 – November 1, 1864)

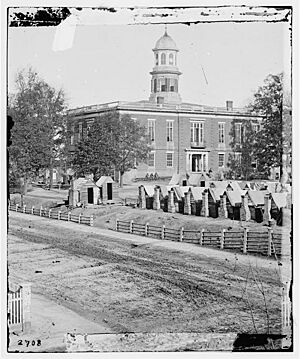

General Sherman ordered his chief engineer, Captain Orlando M. Poe, to build new defenses around Atlanta. Captain Poe found the existing Confederate forts too large for the number of troops Sherman planned to leave in the city. So, he designed a new, smaller defense line closer to the city center. This new line required many buildings to be torn down.

Work on the new defenses began on October 3, 1864. Captain Poe reported that they had completed positions for thirty cannons within the first week. Work continued until November 1.

Destroying Military Assets (November 7–16, 1864)

General Sherman decided to abandon Atlanta because occupying it tied up too many soldiers. His plan was to destroy all military assets in the city, reorganize his forces, and then march through Georgia to destroy the state's ability to fight.

On October 19, 1864, Sherman told his officers that he planned to destroy the railroad from Chattanooga to Atlanta, including Atlanta itself. He wanted to "sally forth to ruin Georgia and bring up on the seashore." He ordered all unnecessary items to be sent away and to have enough food for 30 days.

Sherman ordered Colonel Cogswell and Captain Poe to plan the destruction of Atlanta's transportation and manufacturing centers. They planned to demolish specific buildings and railroad areas. The plan did not include destroying private homes.

On November 7, General Sherman instructed Captain Poe to "take special charge of the destruction in Atlanta of all depots, car-houses, shops, factories, foundries." He told Poe to knock down chimneys and break arches, noting that "fire will do most of the work."

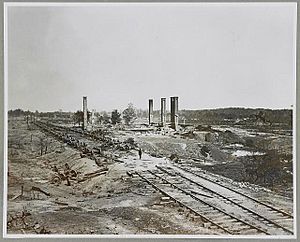

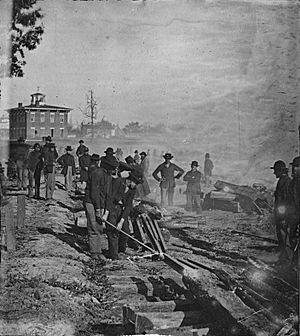

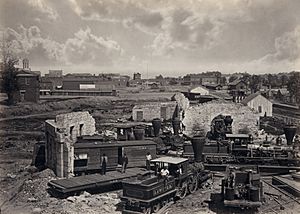

The destruction of Atlanta's military assets began on November 12 and continued until the evening of November 15, 1864. Engineer troops systematically destroyed buildings by battering down walls, throwing down smokestacks, and breaking machinery. Railroad tracks were torn up, heated over burning ties, and then twisted so they couldn't be used again. About ten miles of railroad were destroyed this way. The train depot, car sheds, and machine shops were also destroyed.

Fire was applied to the piles of rubble on the evening of November 15. While the engineer troops worked in an orderly way, many buildings in the business part of the city were also burned by "lawless persons" who set fires in alleys.

General Sherman returned to Atlanta on November 14. He noted in his memoirs that the city's great depot, roundhouse, and machine shops were leveled and burning. He mentioned that the fire reached stores near the depot, and the "heart of the city was in flames all night." However, the fire did not reach the courthouse or most of the homes.

After a plea from Father Thomas O'Reilly, Sherman did not burn the city's churches or hospitals. However, other war resources were destroyed. Captain Poe later wrote about his sadness over the "destruction of private property."

Sherman's March to the Sea Begins (November 15–16, 1864)

On November 15, while destruction continued in downtown Atlanta, the main Union forces began their "March to the Sea." The army, about 60,000 men, was divided into two wings. The right wing marched south towards Jonesboro, following the Macon & Western Railroad. The left wing marched along the Georgia Railroad towards Decatur and Stone Mountain.

As General Sherman left Atlanta at 7:00 a.m. on November 16, he looked back at his work. He wrote that Atlanta was "smoldering and in ruins, the black smoke rising high in air, and hanging like a pall over the ruined city."

Atlantans Return (November 17, 1864 – May 4, 1865)

After the Union forces left, one of the first Atlantans to return was Zachary Rice on November 20, 1864. He reported that many streets were completely burned, with no houses standing. He noted that some churches near City Hall were saved, but others were destroyed.

James R. Crew, Mayor Calhoun's representative, wrote to his wife on December 1, 1864, that "two-thirds at least" of the city had been destroyed by fire.

On November 26, 1864, Colonel Luther J. Glenn was appointed commander of Atlanta. On December 5, Captain Thomas L. Dodd became the city's military police chief.

General W. P. Howard inspected the city on December 7, 1864. He reported that several major buildings, like the City Hall, the Gate City Hotel, and some churches, were not destroyed. However, many businesses, private homes, and other churches were ruined. He also noted that people were looting the city, taking pianos, mirrors, furniture, and other valuable items.

The destruction of Atlanta happened because of several events:

- Confederate defenses were built in 1863.

- The city was shelled during the siege from July to August 1864.

- Union forces tore down houses for shelter and firewood.

- Fighting between armies destroyed homes in the "no-man's-land."

- Confederates destroyed military supplies when they left in September 1864.

- Union troops built temporary shelters during their occupation.

- Union troops built new inner defenses in October 1864.

- Union troops deliberately destroyed railroads, factories, and warehouses from November 12-15, 1864.

- Unauthorized fires were set by Union troops from November 11-15, 1864.

Newspapers in December 1864 encouraged citizens to return and rebuild. The Atlanta Intelligence reported that "one-third of Atlanta still lives" and would be the "nucleus" for rebuilding. The Augusta Chronicle & Sentinel estimated that "about three fourths of the buildings have been torn down or burned."

More and more citizens returned in December 1864. The Augusta Chronicle & Sentinel reported that "many of the old citizens are returning, and the general watchword is repair and rebuild." Businesses began to reopen.

Elections were held, and James Calhoun was re-elected Mayor. The city council met on January 6, 1865, and the city treasury had only $1.64. By April 1865, five churches were holding services again.

After the Battle of Bentonville, General Joseph E. Johnston surrendered the Confederate Army of Tennessee on April 26, 1865. On May 4, 1865, Union Colonel Beroth B. Eggleston officially accepted the surrender of Confederate troops in Atlanta.

Aftermath

The fall of Atlanta was very important for politics. Northern newspapers covered the capture of the city widely, which greatly boosted morale in the North. This helped Abraham Lincoln win re-election easily.

After the war, Federal troops returned to Atlanta to help with Reconstruction, the period of rebuilding the South.

Images for kids

See Also