Avon Gorge facts for kids

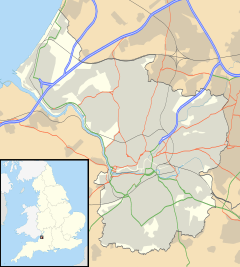

The Avon Gorge is a long, narrow valley about 2.5 kilometers (1.5 miles) long. It was carved out by the River Avon in Bristol, England. This amazing gorge cuts through a ridge made of limestone rock, just west of Bristol city center. It's also about 5 kilometers (3 miles) from where the river meets the sea at Avonmouth. The gorge acts as the natural border between North Somerset and Bristol. Since Bristol was an important port, the gorge was like a natural defense for the city.

On the east side of the gorge, you'll find the Bristol area called Clifton and The Downs, which is a big public park. To the west is Leigh Woods, a village and a forest managed by the National Trust. High above the gorge, there are three old Iron Age hill forts and an observatory. The famous Clifton Suspension Bridge, a symbol of Bristol, stretches across the gorge.

Contents

How the Gorge Was Made

The Avon Gorge cuts through a ridge made mostly of limestone, with some sandstone. This limestone formed about 350 million years ago, during the Carboniferous period. Back then, this area was covered by shallow tropical seas, which is why we find fossils of shells and corals in the rock.

For a long time, scientists wondered why the River Avon cut through this hard limestone ridge instead of flowing an easier way. It's now thought that during the Anglian ice age, glaciers blocked the river's usual path. This forced the river to carve out the gorge we see today. At the Clifton Suspension Bridge, the gorge is more than 210 meters (700 feet) wide and 90 meters (300 feet) deep!

In the 1700s, people started quarrying (digging for) stone in the gorge. This stone was used to build parts of Bristol. Later, in the 1800s, a mineral called celestine was found. Bristol became a major producer of celestine for a while. You can also find "Bristol Diamonds" here, which are shiny quartz crystals inside rocks. These were popular souvenirs for visitors to the nearby Hotwells spa. Today, the old quarries are popular spots for rock climbers and are home to amazing wildlife like Peregrine falcons.

Amazing Nature and Wildlife

The steep sides of the Avon Gorge are home to some very rare plants and animals. There are 24 rare plant species, including two types of trees found only here: the Bristol and Wilmotts's whitebeams. Other special plants include Bristol rock cress, Bristol onion, and spiked speedwell. Because the sides are so steep, many areas don't have large trees, allowing smaller plants to thrive. The gorge also has rare invertebrates (animals without backbones).

The gorge has its own special weather, called a microclimate, which is about 1 degree warmer than the surrounding land. The south-west facing sides get lots of afternoon sun, but they are also partly protected from strong winds.

The steep walls are perfect for peregrine falcons, which are fast birds of prey. They have plenty of food nearby, like pigeons and gulls. Peregrines have nested in the gorge for a long time. After almost disappearing from Britain, they returned to the gorge in 1990 and have been breeding successfully almost every year since. On warm days, birds of prey love to soar on the rising air currents in the gorge while they hunt. The gorge is also home to many Jackdaws and horseshoe bats, which live in the caves and under the bridge.

Because of its unique rocks and wildlife, a large part of the gorge and the nearby woods is protected. It's called a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). The National Trust owns most of the Leigh Woods side of the gorge. The Downs, on the Bristol side, are a public park managed by Bristol City Council. Protecting the gorge's nature while allowing people to enjoy activities like rock climbing is a big job!

Some other rare plants found here include Green-flowered helleborine, lady orchid, fly orchid, and bee orchid. The Bristol rock-cress is also found here, with thousands of plants growing on both sides of the gorge.

A Look at Human History

People have lived in the Avon Gorge area since at least the Iron Age. The Dobunni tribe likely lived here. Above Nightingale Valley, near the suspension bridge, is Stokeleigh Camp. This is one of three Iron Age hill forts in the area. Stokeleigh was used for hundreds of years and is now a protected historical site. These forts probably helped defend the gorge.

During the Middle Ages and the Industrial Revolution, the area that is now The Downs was used for grazing animals. People also mined for lead, iron, and limestone here. There was even a windmill that made snuff (a type of tobacco) from tobacco imported into Bristol. In 1777, the windmill burned down and was turned into the Clifton Observatory, which has a camera obscura.

In the 1700s and 1800s, Bristol's economy grew, and Clifton became a popular place to live. Big houses were built overlooking the gorge. Later, an Act of Parliament was passed to protect The Downs as a park for everyone in Bristol.

The idea of building a bridge across the gorge came up in 1754. But it took almost 80 years for work to begin on Isambard Kingdom Brunel's Clifton Suspension Bridge, and another 30 years for it to be finished. Today, the bridge is one of Bristol's most famous landmarks.

The gorge has always been a key transport route. It carries the River Avon, major roads, and two railways. It's the entrance to Bristol Harbour and offered protection from storms or attacks. The Bristol Channel has very high tides, making the narrow and winding gorge tricky to navigate. Many ships have run aground here over the years. The saying "ship shape and Bristol fashion" comes from a time when Bristol's harbor was tidal. If ships weren't built strongly, they would break apart when the tide went out!

Railways were built through the gorge in the 1860s. One, the Bristol Port Railway, was later partly replaced by a major road called the Portway, which opened in 1926. This road is now part of the A4 road, connecting Bristol city center to the M5 motorway.

Two railways still run through the gorge today. On the east side, the Severn Beach Line uses part of the old Bristol Port Railway. On the west side, the Portishead Railway was closed in the 1960s but has since reopened for freight. There are plans to reopen it for passengers too. From 1893 to 1934, the Clifton Rocks Railway carried passengers up and down the steep gorge side.

Today, a footpath and a National Cycle Network cycleway run along the gorge, perfect for walking and cycling. The gorge is also a popular spot for rock climbing, with many routes for climbers to explore.

Giants and Legends

There's an old story about how the Avon Gorge was formed. It's a legend about two giant brothers, Goram and Vincent, who supposedly created the gorge.

One version of the story says that Goram and Vincent were digging the gorge together. Goram fell asleep, and Vincent accidentally killed him with his pickaxe. Another story says the brothers both fell in love with a girl named Avona. She told them to drain a big lake that stretched across the Avon valley.

Goram started digging a different gorge nearby, but he drank too much beer and fell asleep. Vincent kept digging the Avon Gorge and drained the lake, winning Avona's heart. When Goram woke up, he was so angry that he stamped his foot, creating "The Giant's Footprint" in the ground. Then he threw himself into the Bristol Channel, turning into stone. His head and shoulder are said to be the islands of Flat Holm and Steep Holm.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |