Bachman's warbler facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Bachman's warbler |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Live bird photographed by Jerry A. Payne in 1958 | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Parulidae |

| Genus: | Vermivora |

| Species: |

V. bachmanii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Vermivora bachmanii Audubon, 1833

|

|

|

|

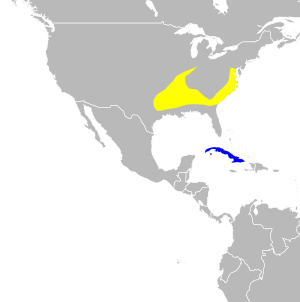

| Former range of V. bachmanii Breeding range Winter range | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Bachman's warbler (Vermivora bachmanii) is a tiny bird that travels long distances. It's either critically endangered or possibly even extinct. This warbler used to breed in swampy areas of the southeastern United States. It spent its winters in Cuba. There have been a few possible sightings in the 2000s, but experts haven't widely confirmed them. The last clear sightings of this bird were in the 1960s. Some people believe a sighting in Louisiana in 1988 was real, but it's still debated.

Contents

Meet the Bachman's Warbler

How Was This Bird Discovered?

A reverend named John Bachman first found this bird in 1832. He saw it near Charleston, South Carolina. Bachman sent drawings and descriptions to his friend, the famous artist John James Audubon. Audubon never saw a live Bachman's warbler. But he named the bird in honor of Bachman in 1833.

The Bachman's warbler doesn't have many very close relatives. However, the blue-winged warbler and the golden-winged warbler are thought to be its closest family members. These birds are all part of the Vermivora genus. There were no known types or subspecies of the Bachman's warbler.

What Did It Look Like?

Bachman's warblers looked different depending on if they were male or female. Their feathers also changed between spring and fall.

In spring, adult males had a bright yellow forehead and face. The area below their eye was yellow, but the area near their beak was a dark olive color. The top of their head was black with gray edges. The back of their head and neck were olive-gray. The rest of their upper body was olive green, with the rump (lower back) being the brightest. Their chin and upper throat were yellow, while their chest was black. Their belly was yellow, and the feathers under their tail were white. Young males in their first spring looked similar but had less black on their head and chest.

Adult females in spring had a light yellow forehead that blended into a gray head and neck. Their face near the beak was gray-olive, and they had a white ring around their eye. The rest of their upper body was olive-green, brightest on the rump. Their chin and throat were light yellow. The sides of their neck and upper chest were gray. Older females sometimes had a few black feathers on their upper chest. The rest of their chest and belly were light yellow, turning white under the tail. Their sides were also a bit gray. Young females in their first spring looked duller than adult females.

Bachman's warblers changed their feathers in the summer for fall. For adult males, their fall feathers were almost the same as spring. The only difference was that the black on their forehead turned gray. Young males also looked like their spring selves, but their forehead was olive and their yellow underparts were duller. Adult females kept the same feathers, but they looked fresher in the fall. Young females had an olive-yellow forehead and a dull eye-ring.

Baby Bachman's warblers got their first feathers in May. They were dusky brown on their head and upper body. Their underside was a paler brown, turning dull white on their lower body and under their tail.

This warbler was about 4.25 inches (10.8 cm) long. It was quite small for a warbler and had a short tail. It was special because its beak was thin and curved downwards. The beak was blackish-brown in adults and brown in young birds. Their legs were grayish-brown, and their eyes were dark brown.

What Did It Sound Like?

The songs of the Bachman's warbler were a fast series of 6 to 25 buzzing notes. Sometimes, the song ended with a sharp, slurred note that sounded like zip. Its song was similar to the northern parula's song, but it was more monotone. People recorded several call notes, from a soft tsip to a low, hissing zee-e-eep.

Where Did It Live?

Bachman's warblers mainly bred in two areas. One was the southern Atlantic coastal plain, and the other was the Gulf Coast states, stretching north along the Mississippi River to Kentucky. In the southern Atlantic coastal plain, they bred near Charleston, South Carolina. They might have once bred as far north as Virginia and south into Georgia. The Gulf Coast breeding area was mostly in central Alabama. There were also reports from northern Mississippi and Louisiana. They bred north of Alabama along the St. Francis River in Arkansas and Missouri. Some unconfirmed reports suggested they bred in eastern Texas, Oklahoma, and Tennessee.

During migration, these birds were mostly seen in Florida and the Florida Keys. A few birds also traveled along the eastern Gulf Coast. There was one record of a spring migration in the Bahamas in 1901. The species mainly spent its winters in Cuba. They were also recorded wintering on the Isle of Pines. One wintering record is known from Florida. There are also unconfirmed reports of them wintering in Georgia's Okefenokee Swamp.

What Was Its Home Like?

Bachman's warblers bred in swampy forests with still water. These forests had mostly deciduous trees like cypress, sweet gum, dogwood, red oak, hickory, black gum, and tupelo. We don't know exactly where in these swamps they preferred to live. But it's thought they liked small open areas created by fires or storms. These spots had a thick undergrowth of cane plants (Arundinaria gigantea) and palmettos. Some experts believe this bird might have specialized in living among cane plants.

When migrating, the warblers still preferred swampy forests. But they were also seen in scrubby areas if swamps weren't available. During the Cuban winter, they seemed to live in many types of forests. This included dry forests, city parks, and swamps. Hibiscus forests might have been important for them.

Life and Habits

Because this bird is so rare, we don't know much about its behavior. This species didn't often pump its tail up and down. When it felt scared, the Bachman's warbler would jerk its tail and raise the feathers on its head.

This bird didn't sing much while migrating. But it did sing once it reached its breeding grounds. There, it liked to sing from high branches. The female warbler sat on the eggs to keep them warm, while the male looked for food.

This species usually looked for food low to the ground, often between three and ten feet high. However, during migration, it was also seen looking for food in the tops of trees. This bird could even hang upside down to search the undersides of leaves. Bachman's warblers found food by picking insects off leaves and poking into leaf clusters. This poking behavior made some people think this warbler specialized in finding food among dead leaves in canebrakes. Its main food included caterpillars, spiders, and other small creatures. It might have eaten nectar in Cuba, but this isn't proven.

It's possible they nested in groups. Their nests were deep and bulky. The outside was made of dead leaves, moss, grasses, and plant stalks. The inside was lined with fine fibers from Ramalina lichen and Spanish moss. These nests were built among blackberry bushes, cane stalks, and palmettos in swampy forests. They were usually 1 to 4 feet above the ground, or often above pools of water. Unlike most warblers, their eggs were pure white. Sometimes they had tiny marks at the wider end.

When Did They Migrate?

Bachman's warblers migrated quite early compared to other New World warblers. Their spring migration started in late February. Birds appeared in south Florida and southeastern Louisiana by the first week of March. The busiest time for migration in south Florida was the first three weeks of March. Along the northwestern Florida coast, it was the third and fourth week of March. The latest a Bachman's warbler was seen in Florida was April 9. These warblers reached their South Carolina breeding grounds around mid-March, though some arrived in late February. Birds migrating to southeastern Missouri arrived between mid and late April. Some birds flew past their breeding grounds and were found in Virginia and North Carolina.

In South Carolina, all Bachman's warblers left their breeding grounds by July 19. The busiest time for fall migration isn't well known. But the earliest a migrant was seen in southern Mississippi was July 4. The first migrants at Key West were reported on July 17. All migration happened between late July and August 25. The last reported migrating bird was seen on September 24 in coastal Georgia.

Why Did It Disappear?

The Bachman's warbler was first studied by John Bachman in South Carolina in 1832. Audubon described it in 1833 from the bird skins Bachman sent him. The bird remained mostly unknown until the mid-1880s. It's thought that some logging in the 1800s actually helped the species for a short time. It created more places for them to live. People often saw it in its breeding areas from the mid-1880s to 1910.

However, when people started cutting down whole forests (clear-cutting) instead of just picking certain trees, sightings of this bird became rare. By the 1930s, it was very hard to find. The last clear winter sighting was in 1940. The last male bird collected by scientists was on March 21, 1941, on Deer Island, Mississippi. The last female bird was collected on February 28, 1940, on Ship Island, Mississippi.

Reports of birds from the Missouri and Arkansas breeding grounds continued through the 1940s. Birds were reported breeding in South Carolina's I'on Swamp until 1953. People saw individuals in Fairfax County, Virginia, in 1954 and 1958. A male was seen singing near I'on Swamp in April 1962. On March 30, 1977, a young female was seen in Brevard County, Florida. The last confirmed sighting was in Louisiana in 1988.

Some reliable reports of the species from the Congaree National Park in the early 2000s led to a formal investigation. But these were later thought to be mistakes. People might have confused them with hooded warblers or northern parula songs. A careful search using recorded Bachman's warbler songs didn't find any males defending their territory. It also didn't make other birds react aggressively. The search leaders concluded the species was not in the park during their search.

This species is threatened because its habitat was destroyed. It's believed to have nested in canebrakes, and losing these areas was a big problem. Losing their winter homes in the Caribbean also hurt them. Hunting birds for their feathers (plume hunting) was another threat. While small-scale logging in the 1800s might have helped, clear-cutting their habitat and draining swamps were the main reasons for habitat loss. We don't know if changes in their winter homes in Cuba affected them. But it's thought that a winter hurricane in the 1930s could have been a huge blow. It might have made them too rare to find each other and mate.

In Culture

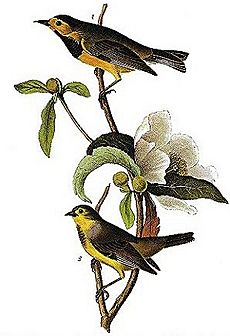

Audubon's famous drawings of a male and female Bachman's warbler were painted on top of an illustration of the Franklinia tree. This tree was first drawn by Maria Martin, Bachman's sister-in-law. She was one of the first female natural history illustrators in the country.

In the comic strip Doonesbury, a bird watcher named Dick Davenport died in 1986. He had a heart attack while watching and photographing this species. This death scene is remembered as a very famous moment in comic history.

- Bachman's Warbler: A Species in Peril, second edition, by Paul B. Hamel. You can read the full book online.

See also

In Spanish: Bijirita de Bachman para niños

In Spanish: Bijirita de Bachman para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |