Battle of Vigo Bay facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Vigo Bay |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Spanish Succession | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 25 ships of the line + frigates and fireships |

15 French ships of the line 3 Spanish galleons + frigates, fireships, and transports |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~800 killed | All ships burnt or captured ~2,000 killed |

||||||

The Battle of Vigo Bay, also known as the Battle of Rande, was a big naval fight that happened on October 23, 1702. It took place during the early years of the War of the Spanish Succession. This battle happened after English and Dutch forces tried to capture the Spanish port of Cádiz in September. They wanted to use Cádiz as a naval base in Spain. From there, they hoped to control the western Mediterranean Sea.

However, the attack on Cádiz was a disaster. As Admiral George Rooke sailed home in early October, he heard important news. A Spanish treasure fleet from America, full of silver and goods, had entered Vigo Bay in northern Spain. Even though it was late in the year, Admiral Philips van Almonde convinced Rooke to attack these treasure ships. The ships were protected by strong French warships.

The French and Spanish fleet tried to stay safe behind a huge barrier called a boom. This boom was protected by two gun batteries on land. But the Allied marines captured the land defenses and broke through the boom. Then, the main Anglo-Dutch fleet attacked the French ships, which were outnumbered and stuck. The French lost six ships, and many others were destroyed.

This battle was a huge success for the Allies at sea. The entire French fleet, led by Château-Renault, and the Spanish treasure ships, led by Manuel de Velasco, were either captured or destroyed. Most of the treasure had been unloaded before the attack, so the Allies didn't get as much silver as they hoped. Still, this victory greatly boosted the Allies' spirits. It also helped convince the Portuguese King, Peter II, to leave his agreement with France and join the Grand Alliance.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The War of the Spanish Succession began because the Bourbon family, from France, took over the Spanish throne in 1700. This made other European countries worried about France becoming too powerful. In Spain's American empire, officials and colonists didn't like France trying to control their trade. Dutch and English traders, even though their trade was officially illegal, were usually accepted by the Spanish. But in the Caribbean, French admirals who came to "protect" Spanish silver were viewed with great suspicion.

The Spanish navy was weak, so the government in Madrid had to rely on French warships to protect their treasure ships. They tried hard to make sure the silver was brought to Spain, not France. This was because they feared it might never return from France.

In 1702, naval battles happened in America and Spain. These battles were connected by the Spanish treasure ships sailing across the Atlantic. The main goal for England and the Dutch Republic was to control the Mediterranean Sea. They hoped this would encourage Portugal to join them. It would also open the Strait of Gibraltar and secure English naval power in the Mediterranean. To do this, the Anglo-Dutch fleets needed to capture a port in Spain. So, they planned an expedition led by Admiral George Rooke to capture the southern Spanish port of Cádiz. This would also cut off Spain's trade with America.

Before the Battle

The Silver Fleet's Journey

On June 11, 1702, the Spanish silver fleet left Veracruz, Mexico. It was protected by a French squadron led by Admiral Château-Renault. The Spanish ships were commanded by Manuel de Velasco. His ship, the Jesús María y José, was one of three ships meant to protect the fleet. The whole group of ships arrived in Havana, Cuba, on July 7. Then, they started their journey across the Atlantic on July 24. There were 56 ships in total: 22 Spanish and the rest French. Many of these were merchant ships that sailed to France once they felt safe.

When Château-Renault first sailed to the Caribbean in 1701, war had not yet been declared between France and England/Dutch Republic. But during their journey, the convoy heard that war had started. They also learned that Rooke was blocking Cádiz, which was usually where the silver fleet went. So, they needed a new, safe harbor. Velasco thought about a small port called Los Pasajes. But Château-Renault preferred Brest or La Rochelle in France, or even Lisbon in Portugal. They finally agreed on Vigo Bay in Galicia, Spain. The Franco-Spanish fleet entered Vigo Bay on September 23.

However, unloading the cargo took a very long time. All the officials needed for unloading were in Seville and Cádiz. They had to wait for them to arrive before anything could be taken off the ships. When unloading finally began, they realized they didn't have enough ways to transport the goods. So, they focused on the silver first. It was unloaded and sent inland to Lugo.

The Allies Find Out

By mid-October, the English government learned that the Spanish fleet was in Vigo Bay. They immediately sent messages to find Admiral Rooke and Admiral Cloudesley Shovell. Rooke was already sailing home from the failed attack on Cádiz. That mission had been a disaster because of bad discipline and poor teamwork.

Luckily, Rooke had already heard the news about the Spanish convoy from one of his own ships. Captain Thomas Hardy on the Pembroke had stayed behind to get water in Lagos, Portugal. The Pembroke's chaplain, a man named Beauvoir, heard from the French consul that the treasure ships were in Vigo. A messenger from the Imperial Embassy in Lisbon confirmed this news. Hardy immediately chased after Rooke and found him on October 17, stopping him from crossing the Bay of Biscay.

Admiral Rooke wrote in his journal: "After thinking about the information Captain Hardy brought... We decided to go to Vigo and attack them right away with our whole fleet, or with smaller groups if that works better."

Rooke sent ships to explore the entrance of Vigo Bay. A landing party captured a friar who told them that the King's share of the treasure had already been unloaded. But much wealth was still left on the Spanish ships.

The Battle Begins

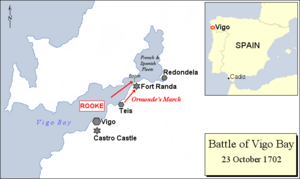

On the evening of October 22, the Anglo-Dutch fleet entered the Ria de Vigo. They sailed past the two forts of Vigo city, which fired at them. At the end of the bay, the French fleet and Spanish treasure ships were in the harbor of Redondela. They were surrounded by the Galician mountains. Château-Renault had set up the defenses. He blocked the narrow entrance, called the Rande Strait, with a strong boom. This boom was made mostly of wood and tightly bound chains.

At the north end of the boom, there was a gun battery with about "fifteen or sixteen" guns. At the south end, there was Fort Rande, a strong stone tower with platforms for cannons. The area between the tower and the water had a fortified wall with another battery that controlled the straits. In total, the Rande defenses had more than 30 guns. To help the French soldiers from the fleet, local troops were also gathered by the Prince of Barbançon, who was the governor of Galicia.

On the Royal Sovereign, the Allied leaders discussed how to attack. The plan was for English and Dutch ships to destroy the boom. At the same time, soldiers from the fleet would silence the guns on shore. This wouldn't be a normal naval battle because Vigo Bay was too narrow for ships to line up. So, Rooke had to change his usual battle plans.

Rooke wrote in his journal: "Considering where Monsieur Château-Renault's ships are... and since the whole fleet cannot attack them without great risk of getting tangled up: we decided to send a group of fifteen English and ten Dutch ships of the line with all the fireships, to do their best to capture or destroy the enemy ships..."

Breaking Through the Boom

Early on the morning of October 23, Vice Admiral Thomas Hopsonn on the Torbay led the attack on the boom. A strong group of English ships and Dutch ships, led by Vice Admiral Philips van der Goes, followed him closely. Château-Renault had placed two of his biggest warships, the Bourbon and the Esperance, near each end of the boom. Inside the boom, he had five other large warships ready to fire at the entrance.

Meanwhile, Ormonde landed with about 2,000 men near Teis. They marched towards Fort Rande. Ormonde sent Lord Shannon with the first group of grenadiers to attack the fort, which was defended by several hundred troops. They stormed the outer wall and silenced the battery near the sea. This helped the ships break the boom. The tower, defended by about 300 French and Spanish troops, held out a little longer. But it also fell to the Allied grenadiers. While Ormonde's men attacked the southern shore guns, the 90-gun Association attacked and silenced the smaller northern battery on the other side of the bay.

The Torbay, helped by a gust of wind, crashed into the boom. The boom broke, and the ship sailed right into the French ships beyond. However, the wind suddenly dropped, stopping other Allied ships from following. Hopsonn found himself alone and outnumbered for a moment. A fireship was placed next to the Torbay, setting it on fire. Luckily for Hopsonn, the fireship, which was full of snuff from the Spanish Indies, suddenly exploded. A huge cloud covered the English ship, partly putting out the flames. This allowed the crew to control the fire. According to Rooke's journal, 53 men drowned in this event. But as the wind picked up, the other Allied ships managed to get through the boom and fight the enemy.

With the boom broken and the forts silenced, the French and Spanish fleet was doomed. Château-Renault's men set fire to their own ships in the harbor and escaped to shore. The Allied sailors worked all night to save the captured ships. By morning, every French or Spanish ship had either been captured or destroyed.

What Happened After

Losses and Gains

The Battle of Vigo Bay was a huge naval disaster for the French. Out of 15 ships of the line, 2 frigates, and one fireship, not a single one escaped. The English captured five ships, and the Dutch captured one. The rest were burned, either by the Allies or by the French themselves. The Spanish also suffered greatly. All three of their galleons and 13 trading vessels were destroyed, except for five that the Allies took.

The Spanish navy was almost completely destroyed. This meant Spain had to rely totally on the French navy to communicate with their colonies in America. However, the Spanish government didn't lose much money. They only owned two of the three large galleons and none of the trading ships. The people who lost the most were private traders. They lost not only the ships but also huge amounts of goods like pepper, cocoa, snuff, and animal hides.

When the news first arrived that the treasure fleet had reached Vigo safely, merchants in Holland celebrated. But later reports of the battle were met with mixed feelings in Amsterdam. This was because much of the wealth captured or destroyed belonged to English and Dutch traders, as well as the Spanish. The Spanish government did own the silver. Most of it had already been unloaded from the ships before the Allied attack. It was eventually stored safely in the castle of Segovia.

So, the Allies didn't capture as much silver as many people thought. Isaac Newton, who was in charge of the Royal Mint, said in June 1703 that they had received about 2,043 kg of silver and 3.4 kg of gold. This was worth about £14,000. Coins made from these metals had the word VIGO under Queen Anne's picture. These coins are now rare and valuable.

In February 1703, King Philip V of Spain ordered that all the silver from the treasure fleet belonging to the English and Dutch be taken. This was his way of getting back at them. This amounted to four million pesos. The King also decided to borrow two million pesos from what belonged to Spanish traders. In total, Philip managed to keep almost seven million pesos. This was more than half the silver from the fleet. It was the largest amount of money any Spanish king had ever gotten from American trade. This meant a huge financial gain for Philip V.

Portugal Changes Sides

The naval victory at Vigo had a big impact on the Grand Alliance. When the Bourbon King Philip V took the Spanish throne, King Peter II of Portugal signed an alliance with France in June 1701. He wanted to stay friends with his powerful neighbor. But protecting Portugal's overseas empire was more important than its land border. To keep Portugal's trade routes from South America safe, the leaders in Lisbon knew they needed to be allied with the strongest naval power in the Atlantic. After Rooke's success at Vigo, it was clear that England and the Dutch Republic had that naval strength.

In May 1703, Portugal signed the Methuen Treaties with England. José da Cunha Brochado, the Portuguese minister in London, said, "To protect our overseas colonies, we must have a good understanding with the powers that now control the sea." He added that it was expensive but essential for Portugal. It was a great victory for the Allies to get Portugal to leave its alliance with France. With Lisbon as a base, the Allied fleet could control the Strait of Gibraltar. This would greatly limit French actions in the Mediterranean.

However, this alliance with Portugal also changed the Allied strategy. England and the Dutch Republic now had to commit to fighting in Spain. One army was based in Lisbon, and another in Catalonia to the east. This policy eventually became a heavy burden and led to a difficult campaign in Spain. But in the long run, the trade agreements in the treaties helped Britain become very wealthy. So, the naval victory at Vigo helped Britain's prosperity in the 1700s.

Sunken Treasure

People started trying to find the sunken treasure almost immediately after the battle. These efforts continued for hundreds of years. After their first tries failed, the Spanish government hired private companies to recover the treasure, but they also didn't succeed. In 1728, a Frenchman named Alexandre Goubert managed to bring a ship almost completely to shore. But he stopped when he realized it was a French warship with no treasure.

An English expedition in 1825, led by William Evans, used a diving bell. Over a year, they managed to find small amounts of silver, cannonballs, and other items. Around the same time, a group called The American Vigo Bay Treasure Company tried to raise a ship, but they ended up tearing it apart. Decades later, Cavalier Pino used his invention, the hydroscope, to scan the area. He mapped out several ships and, after careful experiments, recovered several cannons and preserved wood.

On August 10, 1990, after a sonar survey, the remains of the ship 'Santo Cristo de Maracaibo' were found. It was off the Cíes Islands, about 79 meters deep.

Ships in the Battle

| Ship | Guns | Commander | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mary | 62 | Captain Edward Hopson | Accompanied by Phoenix (fireship) |

| Grafton | 70 | Captain Thomas Harlowe | Accompanied by Vulture (fireship), Captain Thomas Long |

| Torbay | 80 | Vice-Admiral Thomas Hopsonn Captain Andrew Leake |

|

| Kent | 70 | Captain John Jennings | |

| Monmouth | 70 | Captain John Baker | |

| Dordrecht | 72 | Captain Barend van der Pott | |

| Seven Provinces | 92 | Vice-Admiral Philips van der Goes Captain Starrenburgh |

Accompanied by one fireship |

| Veluwe | 64 | Captain Baron van Wassenaer | |

| Berwick | 70 | Captain Richard Edwards | Accompanied by Terrible (fireship), Captain Edward Rumsey |

| Essex | 70 | Rear-Admiral Sir Stafford Fairborne Captain John Hubbard |

Accompanied by Griffin (fireship), Captain William Scaley |

| Swiftsure | 70 | Captain Robert Wynn | |

| Ranelagh | 80 | Captain Richard Fitzpatrick | |

| Somerset | 80 | Admiral Sir George Rooke Captain Thomas Dilkes |

Accompanied by Hawk (fireship), Captain Bennett Allen |

| Bedford | 70 | Captain Henry Haughton | Accompanied by Hunter (fireship), Commander Sir Charles Rich |

| Slot van Muiden | 72 | Captain Schrijver | |

| Holland | 72 | Lieutenant-Admiral Gerard Callenburgh | Accompanied by one fireship |

| Unie | 94 | Vice-Admiral Baron J. G. van Wassenaer | |

| Reigersbergen | 74 | Captain Lijnslager | |

| Cambridge | 70 | Captain Richard Lestock | |

| Northumberland | 70 | Rear-Admiral John Graydon Captain James Greenaway |

Accompanied by Lightning (fireship), Captain Thomas Mitchell |

| Orford | 70 | Captain John Norris | |

| Pembroke | 60 | Captain Thomas Hardy | |

| Gouda | 64 | Captain Somelsdijk | |

| Wappen van Alkmaar | 72 | Vice-Admiral Anthonij Pieterson | Accompanied by one fireship |

| Catwijk | 72 | Captain Beeckman | |

| Association | 90 | Captain William Bokenham | Attacked forts at mouth of harbour |

| Barfleur | 90 | Captain Francis Wyvill | Attacked forts at mouth of harbour |

| Ship | Guns | Commander | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fort | 70 | Admiral Château-Renault | Burnt |

| Prompt | 76 | Admiral Beaujeu | Captured by the English |

| Assuré | 66 | d'Aligre | Captured by the English |

| Espérance d'Angleterre | 70 | Gallissonnière | Taken, but run ashore and bilged |

| Bourbon | 68 | Montbault | Captured by the Dutch |

| Sirène | 60 | Mongon | Taken, but run ashore and bilged |

| Solide | 50 | Champmeslin | Burnt |

| Ferme | 72 | Beaussier | Captured by the English |

| Prudent | 60 | Grandpré | Burnt |

| Oriflamme | 64 | Tricambault | Burnt |

| Modéré | 56 | L'Autier | Captured by the English |

| Superbe | 70 | Botteville | Taken, but run ashore and bilged |

| Dauphine | 40 | Duplessis | Burnt |

| Volontaire | 46 | Sorel | Taken, but run ashore |

| Triton | 42 | de Court | Captured by the English |

| Entreprenant | 22 | Burnt | |

| Choquante | 8 | Burnt | |

| Favori | 14 | Fireship, burnt | |

| Jesus Maria José | 70 | Taken and destroyed | |

| Bufona | 54 | Taken and destroyed | |

| Capitana de Assogos | 54 | Taken and destroyed |

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Rande para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Rande para niños