Belfast Blitz facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Belfast Blitz |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Strategic bombing campaign of World War II | |||||

Rescue workers searching through rubble after an air raid on Belfast |

|||||

|

|||||

| Belligerents | |||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||

| ~1,000 killed ~1,500 injured 30–50,000 houses damaged |

|||||

The Belfast Blitz was a series of four German air raids on the city of Belfast in Northern Ireland. These attacks happened in April and May 1941 during World War II. They caused many deaths and injuries.

The first small attack was on the night of April 7-8, 1941. It was likely a test of Belfast's defenses. The biggest raid happened on Easter Tuesday, April 15, 1941. About 200 German Luftwaffe bombers targeted factories and military sites. Around 900 people died and 1,500 were hurt. This raid used mostly high-explosive bombs. It was one of the deadliest night raids during the Blitz outside of London.

Two more raids happened in May 1941. On May 4-5, 150 people were killed, mostly by firebombs. The final raid was on May 5-6. In total, over 1,300 houses were destroyed, and thousands more were damaged.

Contents

Why Belfast Was a Target

Before World War II, Belfast's factories and shipyards were getting ready for war. Belfast made many important things for the Allies, like naval ships, aircraft, and weapons. Because of this, the German Luftwaffe saw Belfast as an important target to bomb.

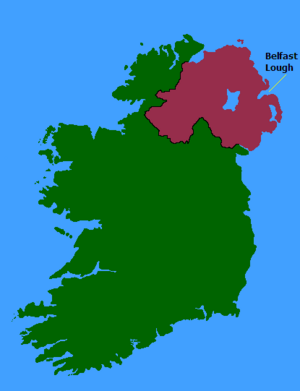

Northern Ireland was part of the United Kingdom. However, the Irish Free State (now the Republic of Ireland) was a separate country. It chose to be neutral during World War II. Even though it arrested German spies, it kept its diplomatic ties with Germany.

Government During the Blitz

The government of Northern Ireland was not well-prepared for a major crisis. Lord Craigavon, who had been Prime Minister since 1921, died in 1940. This left a gap in leadership. John Clarke MacDermott, the Minister of Public Security, tried to organize an evacuation plan after the first bombing. He even asked the Irish government for help.

Some government officials resigned because they felt the government was not doing enough. They believed the government was "slack, slow, and uncaring." J. M. Andrews became Prime Minister after Craigavon, but he also struggled with the situation. He was later replaced by Sir Basil Brooke.

Belfast's War Factories

Belfast had many important factories that helped the war effort:

- Harland and Wolff was one of the world's largest shipyards. It built many ships for the Royal Navy, including aircraft carriers and cruisers. It employed up to 35,000 people.

- During the war, Belfast shipyards built or fixed thousands of naval ships. They also launched many merchant ships.

- Short Brothers made aircraft, like the Sunderland flying boat and the Stirling heavy bomber. About 20,000 people worked there.

- James Mackie & Sons made shells for anti-aircraft guns.

- Harland's Engineering works built tanks, including the Churchill.

- Other factories made aircraft parts, gun mounts, and ammunition.

War supplies and food were sent from Belfast to Great Britain by sea. Some ships even sailed under the neutral Irish flag for protection.

British Preparation for Raids

Northern Ireland was not very prepared for German attacks. Lord Craigavon, the Prime Minister, had said that "Ulster is ready." However, experts warned in 1939 that Belfast was a "very definite German objective." Still, little was done beyond building some shelters near the harbor.

Air-raid Shelters

Belfast was a very crowded city, but it had very few public air-raid shelters. There were only 200 public shelters before the Blitz. About 4,000 families had built their own private Anderson shelters in their gardens. These shelters were made of corrugated iron covered with earth. They helped protect people from falling debris, which caused most injuries.

There were no searchlights in the city until April 10. There was also no way to create a smokescreen to hide the city. Only a few barrage balloons were in place. Belfast was thought to be too far for German bombers, so there were no night-fighter planes to protect it. On the night of the first big raid, no Royal Air Force (RAF) planes flew to stop the German bombers. On the ground, only 7 of the 22 anti-aircraft guns were ready to fire.

Children's Safety

Few children were successfully evacuated from Belfast. The "Hiram Plan" to move people out of the city did not work well. Fewer than 4,000 women and children left, leaving 80,000 more in Belfast. Even soldiers' children were not evacuated, leading to sad results when Victoria Barracks was hit.

German Preparation for Raids

After the war, documents showed that the German Luftwaffe flew a reconnaissance flight over Belfast in November 1940. They found that Belfast had only seven anti-aircraft batteries. This made it the most poorly defended city in the United Kingdom. From their photos, they identified key targets:

- Harland and Wolff shipyard

- Short and Harland aircraft factory

- Belfast's power station

- Victoria Barracks

First Raids

Before the main attacks, there had been some small bombings. These were likely from planes that missed targets in Scotland or England.

On March 24, 1941, John MacDermott, the Minister for Security, warned Prime Minister John Andrews that Belfast was not well protected. He predicted an attack during the next full moon, which would be in April. He was right.

The first planned raid happened on the night of April 7. Six German Heinkel He 111 bombers dropped firebombs, high explosives, and parachute-mines. Casualties were low, with 13 people dying. The biggest loss was a factory floor for making parts of Short Stirling bombers. German pilots reported that Belfast's defenses were "inferior in quality, scanty and insufficient." This raid showed how unprepared Belfast was.

Easter Tuesday Blitz

William Joyce (known as "Lord Haw-Haw") announced on German radio that there would be "Easter eggs for Belfast."

On Easter Tuesday, April 15, 1941, people watching a football match saw a single German Junkers Ju 88 plane flying over Windsor Park.

That evening, over 150 bombers flew from France and the Netherlands towards Belfast. They were Heinkel He 111s, Junkers Ju 88s, and Dornier Do 17s. At 10:40 pm, the air raid sirens sounded. The bombers dropped flares to light up the city. The first attack hit the city's waterworks. High explosives were dropped.

Wave after wave of bombers dropped their bombs. When firebombs fell, the city burned because there wasn't enough water pressure to fight the fires effectively.

Many public buildings were destroyed or badly damaged. These included parts of Belfast City Hall, the Ulster Hospital, and several schools and churches. Many streets in the city center and other areas were heavily bombed. For example, Burke Street was completely wiped out, and all its residents were killed.

There was no defense from the air. The anti-aircraft guns stopped firing because they mistakenly thought they might hit RAF planes. But the RAF did not send any planes. The bombs kept falling until 5 am.

55,000 houses were damaged, leaving 100,000 people temporarily homeless. With about 900 people dead, this was the deadliest night raid during the Blitz outside of London. A stray bomber also attacked Derry, killing 15, and another hit Bangor, killing five. By 4 am, the whole city seemed to be on fire.

At 4:15 am, John MacDermott, the Minister of Public Security, contacted Basil Brooke to ask for help from the Irish government. The railway telegraph link between Belfast and Dublin was still working. A telegram was sent at 4:35 am, asking the Irish Taoiseach, Éamon de Valera, for help.

The Human Impact

Over 900 people died, and 1,500 were injured, with 400 seriously hurt. More than half the houses in the city (50,000) were damaged. 11 churches, two hospitals, and two schools were destroyed.

Seeking Shelter

There were few bomb shelters. One shelter on Hallidays Road was directly hit, killing everyone inside. Many people who survived had taken shelter under their stairs. They were lucky their homes were not directly hit or caught fire. In the New Lodge area, 35 people were crushed to death when a mill wall collapsed.

Major Seán O'Sullivan, who reported for the Dublin government, said that people ran into the streets in a panic. Many were hit by explosions and flying debris. He noted that while some saved their lives by running, many more were killed or injured.

That night, almost 300 people, many from the Protestant Shankill area, found safety in the Clonard Monastery in the Catholic Falls Road. The crypt and cellar were used as an air-raid shelter. People, mostly Protestant women and children, prayed and sang hymns during the bombing.

Dealing with the Dead

The morgue services were only prepared for 200 bodies. 150 bodies remained in the Falls Road baths for three days. They were later buried in a mass grave, with 123 still unidentified. 255 bodies were laid out in St George's Market. Many bodies and body parts could not be identified. Mass graves for unclaimed bodies were dug in the Milltown and Belfast City Cemeteries.

Major O'Sullivan's Report

Major O'Sullivan reported on the intense bombing in areas like the Antrim Road, where bombs fell very close to each other. The area between York Street and the Antrim Road was hit hardest. O'Sullivan felt that the entire civil defense system was completely overwhelmed. He saw terrible injuries, including children needing amputations to be freed from rubble.

He also noted the severe lack of hospital facilities. Nine hours after the raid, he found ambulances still waiting to admit injured people at the Mater Hospital. Professor Flynn, head of the city's casualty service, told him about injuries from shock, blast, and flying debris like glass and stones. O'Sullivan's report concluded that "a second Belfast [raid] would be too horrible to think about."

People Fleeing the City

About 220,000 people fled from Belfast. Many arrived in Fermanagh with only their nightclothes. Over 10,000 officially crossed the border into the Irish Free State. Over 500 received care from the Irish Red Cross in Dublin. Towns like Dromara saw their populations grow from 500 to 2,500. Thousands more found refuge with friends or strangers in nearby towns like Newtownards and Bangor.

Moya Woodside wrote in her diary that the evacuation was becoming a panic. Roads out of town were full of cars with bedding tied on top. People were leaving from all parts of the city, not just the bombed areas. No one knew where they were going or what they would eat.

After the Raids

Help from the South

Within two hours of the request for help, 71 firemen with 13 fire trucks from Dundalk, Drogheda, Dublin, and Dún Laoghaire were on their way to Belfast. All the firemen volunteered, even though it was beyond their normal duties. They stayed for three days until the Northern Ireland government sent them back. By then, 250 firemen from other British cities had arrived.

Taoiseach Éamon de Valera formally protested to Berlin about the bombing. He then gave a famous speech in Castlebar, County Mayo, on April 20, 1941. He said:

In the past, and probably in the present, too, a number of them did not see eye to eye with us politically, but they are our people – we are one and the same people – and their sorrows in the present instance are also our sorrows; and I want to say to them that any help we can give to them in the present time we will give to them whole-heartedly, believing that were the circumstances reversed they would also give us their help whole-heartedly ...

Blame and Theories

Some people blamed the government for not taking enough precautions. Tommy Henderson, a local politician, said that Catholics and Protestants were helping each other and agreed that the government was not doing a good job.

An American journalist, Ben Robertson, reported that Dublin was the only city without a blackout between New York and Moscow. He said German bombers often used Dublin's lights to find their way, which angered the British. One common belief was that the Germans found Belfast by flying towards Dublin and then following the railway lines north. Some writers, however, say that Belfast was "too far north" for radio guidance and that its location at the end of Belfast Lough made it easy to find.

Firemen Return Home

After three days, the fire crews from the Irish Free State began to pack up and head home. Most of the major fires were under control, and firemen from other British cities had arrived. The Irish firemen were exhausted. In 1995, on the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II, the Dublin Fire Brigade was invited to a ceremony at Hillsborough Castle. One survivor, Tom Coleman, attended to receive thanks for their help.

Second Major Raid

There was another large air raid on Belfast on May 4-5, 1941, three weeks after the Easter Tuesday attack. Around 1 am, German bombers focused on the Harbour Estate and Queen's Island. Nearby homes in east Belfast were also hit. They dropped over 200 metric tons of high explosives and thousands of firebombs. Over 150 people died in what was called the 'Fire Blitz'.

Fewer people died this time because the sirens had sounded earlier, and the German planes attacked from a higher altitude. St George's Church was damaged by fire. Again, the Irish emergency services crossed the border to help, this time without waiting for an invitation.

Media Depictions

The 2017 film Zoo shows an air raid during the Belfast Blitz.

See also

- The Blitz

- Aerial bombing of cities

- Harland and Wolff

- Belfast

- The Emergency

- Bombing of Dublin in World War II

- Ulster Defence Volunteers

Sources

- Brian Barton (2015). The Belfast Blitz: The City in the War Years. Ulster Historical Foundation, 655pp, new extended edition.

- RS Davison, "The Belfast Blitz", The Irish Sword, Vol. XVI, No.63 (1985).

- Stephen Douds, Belfast Blitz: The People's Story, Blackstaff Press, 192pp. (Belfast 2011).

- Robert Fisk, In Time of War: Ireland, Ulster and the price of neutrality 1939–45 (Dublin 1983).

- Tony Gray, The Lost Years: The Emergency in Ireland 1939–1945. ISBN: 0-7515-2333-X.

- Elaine McClure, Bodies in our Backyard, Ulster Society Publications (Lurgan 1993).

- Brian Moore, The Emperor of Ice Cream, novel set in the Belfast Blitz. McClelland and Stewart (Canada), 1965.

- John Potter, The Belfast Blitz http://www.niwarmemorial.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/The_Belfast_Blitz.pdf

- Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, Historical Topics Series 2, The Belfast Blitz, 2007, http://www.proni.gov.uk/historical_topics_series_-_02_-_the_belfast_blitz.pdf

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |