Black people in Ireland facts for kids

| Total population | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Languages | |

| Hiberno-English, Irish, African languages |

Black people, also known as people of color, have lived in Ireland for a long time. They first arrived in small numbers around the 1700s. Back then, most of them lived in bigger cities and towns like Limerick, Cork, Belfast, Waterford, and Dublin. Over time, more people have moved to Ireland, and the Black community has grown across the country. In 2016, about 39,834 people in Ireland said they were Black or Black Irish with African roots. Another 2,863 people said they had other Black backgrounds.

Contents

A Look Back in Time

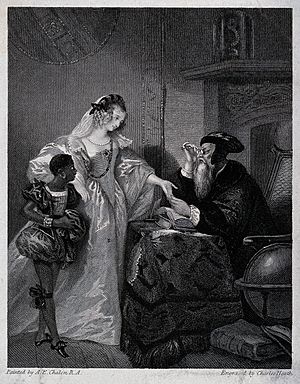

In the 1700s, it was quite common for rich Irish families to have Black servants. This was a way to show off their wealth and high status. Having a young Black servant helping an Irish lady was seen as a sign of being very rich and important.

One famous Black servant in Ireland was Tony Small. During the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), Tony escaped from his owners in South Carolina. He found Lord Edward FitzGerald, an Irish nobleman, who was very sick. Tony helped him get better. When Lord Fitzgerald returned to Ireland, Tony Small became a close friend of the family. Later, Tony met his future wife, Julia, in London. They had three children and started their own business in London.

Not all Black people in Ireland during this time were enslaved. Many were free workers, like musicians, artists, soldiers, or tradesmen. Some servants even earned a salary. A few formerly enslaved Black Americans also moved to Ireland. Besides Tony Small, a preacher named John Jea and a scholar named William G. Allen lived in Ireland for several years.

Many Black people who settled in Ireland became part of the wider Irish community. They married white Irish people and had children. For example, 'Mulatto Jack' was a child of mixed parents. He was taken from Ireland in the early 1700s and sold as a slave in Antigua. After he helped plan a slave uprising, he was sent back to Ireland. The Black Irish singer, Rachel Baptist, is also believed to have married a white person in the 1760s.

Other formerly enslaved people who visited Ireland include Olaudah Equiano and Frederick Douglass.

People from the Afro-Caribbean islands, whose ancestors were Irish immigrants, often have Irish last names. They might speak a type of Caribbean English that sounds a bit Irish. Sometimes, they even sing Irish songs.

Ireland Since the 1900s

Republic of Ireland

The 1960s

In the 1960s, the Irish government started programs to bring students from African countries to Ireland. The idea was to teach them useful skills that they could take back home to help their newly independent countries grow. In 1962, there were 1,100 African students in Ireland. This was about one-tenth of all students in the country. Many of these programs were helped by Irish missionary groups. Some African students even received military training in Ireland. They chose Ireland because it had no history of ruling other countries. Most of these students returned home after finishing their studies. However, from the 1960s to the 1990s, the African population in Ireland also included visitors and professionals like doctors.

The Celtic Tiger Years

Ireland's non-white population started to grow a lot during the "Celtic Tiger" period (1997-2009). This was a time when Ireland's economy grew very fast. One reason for this growth was Ireland's citizenship laws. For a while, these laws allowed parents who were not Irish citizens to stay in Ireland if their children were born there and became Irish citizens. In 2001, the government even invited people from other countries to come to Ireland. A government leader visited five countries in Africa, including Nigeria and South Africa, which led to many people moving to Ireland. However, this automatic right to stay ended in 2007.

Because Ireland is an English-speaking country, many Black people in Ireland are immigrants from (or have family from) Commonwealth countries in the Caribbean and Africa. The rules for Irish citizenship were changed in 2004.

In 2006, the Irish census counted 40,525 people of Black African background and 3,793 people of other Black backgrounds living in the Republic of Ireland. This meant about 1.06% of the population identified as Black. By 2011, these numbers grew to 58,697 people of Black African background and 6,381 people of other Black backgrounds. This made up about 1.42% of the population.

The "Celtic Tiger" boom also led to more people moving to Ireland from all over the world, including Africa. This caused delays in processing applications for people wanting to live in Ireland. For people from outside the European Union, this led to stricter laws and many people being sent back to their home countries if they didn't qualify for asylum or entry.

Some areas in Ireland have larger groups of people from Sub-Saharan Africa. For example, the town of Gort in County Galway has many people from Brazil, including Black and mixed-race individuals.

The 2010s and Today

After the European migrant crisis in 2015, people seeking safety from war zones in North, East, and Central Africa have settled in Ireland. These countries include Eritrea, Sudan, Somalia, the Congo, and Burundi.

Black people in Ireland sometimes face challenges. These include everyday racism, old stereotypes, and unfair treatment in education.

Many people seeking safety from African countries live in Ireland's Direct Provision system. This is a system for people asking for asylum. It has been criticized because it can take a very long time for applications to be processed, and the living conditions are often poor.

Northern Ireland

World War II

During World War II, many African American soldiers were stationed in Northern Ireland. People in Northern Ireland generally welcomed them, seeing them mostly as Americans. The local government did not agree to set up separate areas for Black and white soldiers, as the American military wanted. However, there were still some cases of unfair treatment and racism, often due to a lack of understanding. It is thought that white and Black American troops were treated differently by the Northern Irish people, especially later in the war. The fact that there wasn't a strict rule against mixing helped Black soldiers feel that they could achieve equality back home. Many local women who had relationships with American soldiers, whether Black or white, sometimes faced disapproval from their communities. News reports about Black American troops often used stereotypes, even when the stories were positive. Although the government didn't keep records of mixed-race births, it's known that several mixed-race children were born. The equal treatment between white and Black soldiers also made some white soldiers angry.

The Troubles

During The Troubles, a period of conflict in Northern Ireland, some Black people from mainland Britain served as part of the British Army. A small number of the people who died during this conflict were Black, including both soldiers and civilians.

After the Good Friday Agreement

In 2001, the census in Northern Ireland showed that 1,136 people identified as Black. This included 255 people who said they were Black Caribbean, 494 as Black African, and 387 as Other Black. This number does not include people who said they were of mixed race. By the 2011 census, the number of Black people in Northern Ireland had grown to 3,616, which was 0.2% of the total population.

The Afro-Community Support Organisation Northern Ireland (ACSONI) was created in 2003. It helps represent the views of Black people and is supported by the Equality Commission for Northern Ireland and EU funding. In 2011, ACSONI wrote a report about what other residents thought and knew about Africa and Africans.

Mother and Baby Homes

Between 1922 and 1998, about 275 mixed-race children were born and lived in Mother and Baby Homes in Ireland. When white Irish and Black couples had children, they rarely got married. The children often ended up in these homes, which meant they didn't have full records of their family history. Mixed-race children faced unfair treatment in these homes. Fewer of them were offered for adoption compared to white Irish babies. Many were sent to special wards for children considered "unadoptable" because of their skin color. A report about the Mother and Baby Homes said there was no racial discrimination in these places.

During World War II, from 1942 to 1945, many Black American soldiers were stationed across the UK. Their military bases were often in rural areas. This led to relationships between white British and Irish women and African American soldiers. These relationships often led to pregnancies but rarely to marriage. Children from these relationships often ended up in Mother and Baby Homes or were given up for adoption. Some stayed with their mothers' families. However, mixed-race babies were also born to African students, not just American soldiers.

Black Irish in Politics

Ireland has never elected a Black person to be a Teachta Dála (TD), which is a member of the Irish Parliament, or a Senator. There has also never been a Black cabinet member or a leader of a major government group. Black people are not well represented in Irish politics. Some reasons for this include that people of African descent tend to be younger than the rest of the population. Also, Ireland's voting system can make it hard for minority groups to get elected if they are not all living in one area. It can also be hard for immigrants to make the important connections needed in Irish politics.

In 2007, Rotimi Adebari, a Nigerian refugee, became the first Black mayor in Ireland when he was elected in Portlaoise. In 2011, Darren Scully resigned as mayor of Naas after saying he would not represent "black Africans" because of their "aggressiveness and bad manners."

In 2018, artist Kevin Sharkey tried to run for President but did not get enough support from councils or the Oireachtas (Irish Parliament).

As of 2021, there are only two Black councillors out of 949 in Ireland. These are Cllr. Uruemu Adejinmi, who represents Fianna Fáil on Longford County Council, and Cllr. Yemi Adenuga, who represents Fine Gael on Meath County Council. Yemi Adenuga was the first Black female councillor elected in Ireland. In 2021, Uruemu Adejinmi tried to get a nomination for a Senate election but was not successful. Former asylum seeker Ellie Kisyombe, from Malawi, ran for election in Dublin in 2019. She was the first former asylum seeker to try to get elected in the Republic of Ireland, but she did not win.

In June 2021, Lilian Seenoi-Barr became a councillor for the SDLP in the Derry and Strabane District Council. She is Northern Ireland's first Black councillor.

Impacts on Irish Culture

Religion

More people moving from Africa has led to an increase in the number of Protestant followers in Ireland. This has helped to reverse a decline in their numbers. Many Catholic priests from African countries have also moved to Ireland, helping with the decreasing number of priests in Irish churches.

Poetry, Written, and Spoken Work

The poem 'For Our Mothers', by Nigerian-Irish poet Felicia Olusanya (FeliSpeaks), is part of the 2023 Leaving Certificate school curriculum. Author Emma Dabiri is one of several Irish authors with African heritage.

In July 2021, a team from Maynooth University, made up of Rí Anumudu and Chikemka Abuchi-Ogbonda, became the first Black Irish team to win the important Irish Times Debating Competition.

Irish Language

Many Irish people of African descent are Gaeilgeoirs (speakers of the Irish language). They are also helping the language to grow and change.

Sport

Several players on Ireland's national football team have African heritage.

Notable People

Black people in Ireland

- Rotimi Adebari, Irish politician

- Ifrah Ahmed, Irish social activist

- Kwame Ampadu, Irish former footballer

- Robert Baloucoune, Irish rugby union player

- Gavin Bazunu, Irish goalkeeper

- Denise Chaila, Irish Zambian rapper, singer, poet, grime and hip hop artist

- Erica Cody, Irish R&B singer-songwriter

- Christine Buckley, Irish activist

- Ultan Dillane, Irish Rugby player

- Lucia Evans, Irish-Zimbabwean singer

- Kwaku Fortune, Irish actor

- Garnett sisters, Irish singer-songwriters of Sierra Leonean descent

- Marsha Hunt, American actress, singer, and writer

- Adam Idah, Irish professional footballer

- Kamal Ibrahim, Irish television presenter and actor

- Laura Izibor, Irish recording artist

- Jafaris, Irish rapper, singer and songwriter

- Roberto Lopes footballer

- Paul McGrath, Irish former footballer

- Omero Mumba, Irish actor and singer

- Samantha Mumba, Irish actor and singer

- Ruth Negga, Irish actress

- Cassia O'Reilly, Irish singer-songwriter and music producer

- Paul Osam, Irish former footballer

- Kevin Sharkey, Irish artist, political activist, and former television presenter

- Christopher Simpson, Irish actor of Irish-Greek-Rwandan descent

- Rejjie Snow, Irish rapper

- Soulé, Irish pop singer-songwriter

- Darren Sutherland former boxer

- Pamela Uba, Irish scientist, model and Miss Ireland 2021

- Derrick Williams, Irish footballer

- Simon Zebo, Irish rugby union player

- Caleb Folan

- Leon Best

- Steven Reid

Black Irish Emigrants

Emigrants to France

- Kwame Ampadu, Irish former footballer

Emigrants to Great Britain

- Emma Dabiri, author, academic, and broadcaster

- Layla Flaherty, Irish actress and model

- Rianna Jarrett, Irish footballer

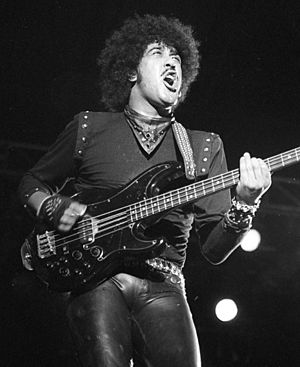

- Phil Lynott, English-born Irish rock singer. Bassist and lead vocalist of Thin Lizzy

- Cassia O'Reilly, Irish singer-songwriter

- Darren Randolph, Irish footballer

- Christopher Simpson, Irish actor

Emigrants to United States

- Samantha Mumba, Irish pop singer

- Ruth Negga, Irish actor

- Fionnghuala O'Reilly represented Ireland at the Miss Universe 2019 pageant

Born, Raised and Living in Britain

- Cyrus Christie, footballer

- John Conteh, former boxer

- Gabriel Gbadamosi, writer, poet

- Kit de Waal, Irish writer

- Craig Charles, English-born Irish actor

- Dolores Mantez, Irish actress

- Liam George, footballer

- Chris Hughton, former footballer

- Henry Hughton, former footballer

- David McGoldrick, footballer

- Clinton Morrison, former footballer

- Lanre Oyebanjo, footballer

- Annie Yellowe Palma, British author