Brothertown Indians facts for kids

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 4000 enrolled (as of 2013) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, formerly Mohegan and Pequot | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Mohegan, Pequot, Narragansett, Montauk |

The Brothertown Indians (also called Brotherton) are a Native American tribe. They live in Wisconsin today. This tribe was formed in the late 1700s. It was made up of different groups of Christianized Native Americans from southern New England and eastern Long Island, New York. These groups included parts of the Pequot, Narragansett, Montauk, Tunxis, Niantic, and Mohegan tribes.

After the American Revolutionary War in the 1780s, the Brothertown people moved from New England to New York. There, the Oneida Nation of the Iroquois people gave them land in Oneida County, New York.

Later, in the 1830s, the United States government pressured them to move again. The Brothertown Indians, along with the Stockbridge-Munsee and some Oneida people, moved to Wisconsin. Many walked all the way from New York, while some traveled by ships through the Great Lakes. In 1839, the Brothertown Indians became the first Native American tribe in the U.S. to accept American citizenship. They also agreed to divide their shared tribal land into individual family plots. They did this to avoid being forced to move even further west. During this time, many other tribes, like the Oneida and Lenape (Delaware), were forced to move to Indian Territory (which is now Oklahoma).

Today, the Brothertown Indians are working to get their federal recognition back. They sent a detailed request in 2005. In 2009, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) said that the 1839 act, which gave them citizenship and divided their land, had ended their status as a sovereign tribe. In 2012, the BIA confirmed this decision. They said that only a new law from Congress could restore the tribe's status.

The Brothertown Indians are still trying to get federal recognition. They are one of twelve tribes in Wisconsin. They are the only one that is not recognized by the federal government. As of 2013, the tribe has more than 4,000 members.

Contents

History of the Brothertown Indians

How the Tribe Formed in New England

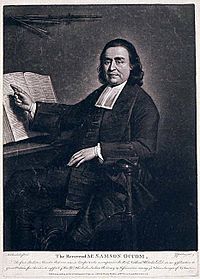

The Brothertown Indian Nation, also known as Eeyamquittoowauconnuck, was started by three important leaders. These leaders were Samson Occom (Mohegan/Brothertown), Joseph Johnson (Mohegan), and David Fowler (Montauk, Pequot). Samson Occom was a well-known Christian minister who worked with Native Americans in New England. He also raised money for a school. Joseph Johnson, Occom's son-in-law, was a messenger for General George Washington during the American Revolution. David Fowler was Occom's brother-in-law.

These leaders brought together many smaller groups of Native Americans. These groups had survived diseases, colonization, and wars. They included people from the Narragansett and Montauk tribes.

After the American Revolutionary War, the tribe officially formed on November 7, 1785. It included Christian Native Americans from Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Long Island, New York. These were people from the Mohegan, Pequot, Narragansett, Niantic, and Tunxis tribes. Some members of these groups chose to stay with their original nations.

American settlers wanted the Native Americans to move west. So, the Brothertown people began to move in the 1780s. The Oneida Nation of the Iroquois, who were allies of the Americans, gave them land in Marshall, New York. This is where they formally became a new tribe. The Oneida were allowed to keep a small reservation in New York. However, because four Iroquois nations had sided with the British during the war, and new settlers wanted more land, New York and the U.S. government pressured tribes to move west of the Mississippi River.

By the 1830s, the Brothertown Indian Nation sold its land in New York. They bought new land in Wisconsin. Today, the tribe has about 4,000 members and is still active.

Treaties to Move West

In 1818, two members of the Brothertown tribe, Isaac Wobby and Jacob Dick, were given land in what is now Delaware County, Indiana. This happened through a treaty with the Delaware people. However, these lands soon ended up being owned by a businessman.

In 1821, many New York tribes signed a treaty with the U.S. government. They gained about 860,000 acres (3,500 sq km) in Wisconsin. In 1822, another group gained even more land, about 6,720,000 acres (27,200 sq km). This was almost the entire western shore of Lake Michigan. The Brothertown Indians were supposed to get about 153,000 acres (620 sq km) along the southeastern side of the Fox River near Kaukauna and Wrightstown. Some tribes felt the government had misled them about the 1821 treaty. This treaty was debated for eight years and was never officially approved by the United States Senate.

The federal government helped settle the issue with three new treaties signed in 1831 and 1832. The Brothertown people agreed to trade their earlier promised lands for 23,040 acres (93.2 sq km). This land is now the entire town of Brothertown in Calumet County, along the east shore of Lake Winnebago.

The Tribe Moves to Wisconsin

The Brothertown leaders wanted their people to live in peace, away from European-American influences. So, they led the move west. The Brothertown joined their neighbors, some of the Oneida tribe and the Stockbridge-Munsee, in planning the move to Wisconsin. Five groups of Brothertown people arrived in Green Bay by ship between 1831 and 1836. They had traveled across the Great Lakes.

Once they arrived, the Brothertown people cleared their shared land and started farming. They also built a church near Jericho. They created a settlement called Eeyawquittoowauconnuck, which they later renamed Brothertown. The federal government soon noticed that their land was good for farming. It then suggested moving the Brothertown even further west to Indian Territory, in what is now Kansas. This was allowed under the Indian Removal Act.

In 1834, the Brothertown Indian Nation asked for U.S. citizenship. They also asked for their tribal land to be divided and given to individual tribal members. They hoped this would stop them from being forced to move west again. On March 3, 1839, Congress passed a law granting the Brothertown Indians U.S. citizenship. This made them the first Native Americans to formally receive it.

One member, William Fowler, served in the Territorial Legislative Assembly of the Wisconsin Territory. Two others, Alonzo D. Dick and William H. Dick, served in the Wisconsin State Assembly. They were the first non-white people to do so. Several tribal members held office in Calumet County, even after the Brothertown were no longer the majority there.

The tribe did not give up their self-governance when they became citizens. The Bureau of Indian Affairs has often said that U.S. citizenship and tribal self-governance can exist together. All Native Americans are now U.S. citizens, but the federal government still recognizes about 573 tribes. In 1878, the federal government met with Brothertown leaders. It suggested that the tribe give up land in the old reservation that had not been given to individual families. The government wanted to sell this land to German immigrants settling in Wisconsin.

Federal Recognition Status

Termination Policy and Its Effects

In the late 1940s and into the 1960s, the U.S. government had a policy called Indian termination policy. This policy aimed to end the special relationship between the federal government and some Native American tribes. The government thought these tribes no longer needed federal support. Several former New York tribes, including the Brothertown, were identified for this policy.

A memo from the Department of the Interior in 1954 mentioned that a bill was being prepared to terminate about 3,600 members of the Oneida Tribe in Wisconsin. Another memo from 1964 stated that the "Emigrant Indians of New York" were "now known as the Oneidas, Stockbridge-Munsee, and Brotherton Indians of Wisconsin."

To fight against termination and get their land claims from New York recognized, these three tribes started legal actions in the 1950s. As a result of a claim filed with the Indian Claims Commission, the group was awarded $1,313,472.65 on August 11, 1964. To share this money, Congress passed a law. This law created separate lists of people from each of the three groups to see who had at least one-quarter "Emigrant New York Indian blood." For the Oneida and Stockbridge-Munsee, the law allowed their tribal governments to approve how the money was given out. This helped end termination efforts for those tribes. However, for the Brothertown Indians, the law said payments should go directly to each person, not through a tribal government. This suggested a different status for the Brothertown.

Working Towards Restoration

In 1978, the federal government created rules for tribes that had lost recognition to help them get it back. That year, the Brothertown tribe sent their first request to regain federal recognition. They want this status to help their members, especially those who live away from their small reservation. They also want to have the same standing as other federally recognized tribes. They believe they have kept their culture and their own government over time.

In 1993, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) agreed that the Brothertown Indians had been recognized as a sovereign tribe by the federal government in treaties from 1831 and 1832, and in the 1839 act that gave them citizenship. The Department of Interior confirmed that the Brothertown Indian Nation could ask the BIA for federal recognition. If Congress's act of granting citizenship had ended their federal recognition in 1839, the tribe would not have been allowed to use the BIA's process. Based on the BIA's decision, the Brothertown Indians spent years gathering information. They sent a detailed request for federal recognition in 2005.

In 2009, the BIA told the Brothertown Indians that they had not met enough of the requirements for recognition. More importantly, the BIA changed its earlier view. It said that the tribe lost its federal status because of the 1839 Congressional act. The BIA stated that Congress had ended the federal government's relationship with the Brothertown tribe in 1839.

In September 2012, the BIA made its final decision on the Brothertown's request. It confirmed that the group had a past relationship with the U.S. government. However, it said that the 1839 Act of Congress had ended their tribal status. Because of this, the Brothertown could not meet one of the main requirements for federal recognition. The BIA said that only Congress can restore the Brothertown's tribal status and their government-to-government relationship with the United States.

The Brothertown Council and their Recognition/Restoration committee have a plan to talk to politicians. They are reaching out to local town leaders and members of Congress to regain tribal status. In an ongoing effort, the tribe asked the Town Board of Brothertown, Wisconsin, for support. However, in a vote on December 27, 2013, the town refused to support their plan to seek Congressional approval.

How the Tribe is Governed

Members of the Brothertown Indian Nation elect their tribal officers. Their tribal council meets every month. They have bought back a small part of their old reservation in Wisconsin. They act with some level of self-governance within the state of Wisconsin. As individual Native Americans, members who meet certain federal rules can have some rights and get federal help, like scholarships. However, not having federal recognition limits their access to some programs.

Culture and Community

The Brothertown people remain a unique Native American community. Most of them live in the Fond du Lac, Wisconsin area. In 1999, the nation had about 2,400 enrolled members. Dr. Faith Ottery, a tribal councilwoman, estimated that by 2013, there were about 4,000 members enrolled in the tribe. She said about 1,800 live in Wisconsin, with half of them within 50 miles (80 km) of the original reservation. About 80% live within 80 miles (130 km). Some tribal members own land within the original reservation boundaries from 1842–45.

Brothertown members have a picnic every July and a homecoming event every October. Many Brothertown Indians have been buried at Union Cemetery in the town of Brothertown, Wisconsin. Quinney Cemetery, just outside the old reservation, is also a burial site. Many Brothertown people visit these graves yearly to honor their ancestors and care for the burial sites. The tribe hopes to buy more land in the original reservation area and build a museum.

Archaeological Project

In 2007, the Brothertown Indian Nation supported an archaeologist named Craig Cipolla from the University of Pennsylvania. He started an archaeological survey and dig at historic Brothertown sites in Wisconsin. He is working to involve Brothertown members and local landowners in the project. The goal is to find, map, and explore sites that need to be protected.

Notable Members

- Thomas Commuck, whose 1845 collection Indian Melodies is thought to be the first published music by a Native American.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |