Cahokia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site |

|

|---|---|

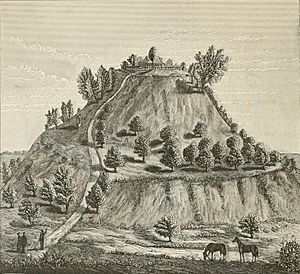

Monks Mound is the largest earthen structure at Cahokia (for scale, people below and on top). About 80 earthen mounds or earthworks survive at the archeology site out of perhaps as many as 120 at the city's apex.

|

|

| Location | St. Clair County, Illinois, U.S. |

| Nearest city | Collinsville, Illinois |

| Area | 2,200 acres (8.9 km2) |

| Governing body | Illinois Historic Preservation Division |

| Official name: Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site | |

| Type: | Cultural |

| Criteria: | iii, iv |

| Designated: | 1982 (6th session) |

| Reference #: | 198 |

| Region: | Europe and North America |

| Official name: Cahokia Mounds | |

| Designated: | October 15, 1966 |

| Reference #: | 66000899 |

| Official name: Cahokia Mounds | |

| Designated: | July 19, 1964 |

Cahokia Mounds is the site of a large Native American city that existed from about 1050 to 1350 CE. It was located across the Mississippi River from where St. Louis is today. This important archaeological park is in southwestern Illinois, between East St. Louis and Collinsville.

The park covers about 2,200 acres (3.5 square miles) and has around 80 man-made mounds. However, the ancient city was much bigger. At its busiest, around 1100 CE, Cahokia covered about 6 square miles. It had about 120 earthen mounds of different sizes and shapes. Between 15,000 and 20,000 people lived there.

Cahokia was the biggest and most important city of the Mississippian culture. This culture built advanced societies across much of what is now the central and southeastern United States, starting around 1000 CE. Today, Cahokia Mounds is considered the largest and most complex ancient site north of the great cities in Mexico.

We don't know the city's original name. The mounds were later named after the Cahokia tribe. This group of Illiniwek people lived in the area when French explorers arrived in the 1600s. Since this was centuries after Cahokia was abandoned, the Cahokia tribe might not have been directly related to the city's first inhabitants. It's likely that many different Native American groups lived in Cahokia during its peak.

Cahokia Mounds is a National Historic Landmark and a protected state site. It is also one of the 26 UNESCO World Heritage Sites in the United States. It's the largest ancient earthen structure in the Americas north of Mexico. The site is open to the public and managed by the Illinois Historic Preservation Division.

Contents

History of Cahokia

Early Beginnings and Growth

Cahokia was settled around 600 CE during the Late Woodland period. People started building mounds here around the 9th century CE. The people of Cahokia didn't leave written records. However, their carefully planned community, mounds, and burials show they were a complex and smart society.

Cahokia became the most important center for the Mississippian culture. This culture spread along major rivers in the Midwest, Eastern, and Southeastern United States. Cahokia was in a great spot near where the Mississippi, Missouri, and Illinois Rivers meet. It traded with communities far away, from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast. They traded valuable items like copper, special stone, shark teeth, and shells.

Around 900 CE, maize (corn) became an important crop for the people of Cahokia. Before this, they mostly grew crops from the Eastern Agricultural Complex, which was an older farming tradition.

The City's Peak (11th and 12th Centuries)

Around 1050 CE, Cahokia grew very quickly in what archaeologists call a "Big Bang." Three main city areas were built: St. Louis, East St. Louis, and Cahokia itself. The city was laid out in a grid, with streets and dozens of mounds pointing north. This new plan replaced older settlements.

Building the city's many earthen mounds was a huge job. Workers dug, excavated, and carried millions of cubic feet of earth by hand in woven baskets. This work took decades. The city had large, flat ceremonial plazas around the mounds. Homes for thousands of people were connected by pathways. This suggests Cahokia was a central religious city where people came for important events.

At its peak, Cahokia was the largest city north of the great cities in Mexico and Central America. Its population grew very fast. Some experts believe it had between 6,000 and 40,000 people at its busiest. If the highest estimates are right, Cahokia was bigger than any city in the United States until Philadelphia grew larger in the 1780s. It might even have been larger than London and Paris at the same time!

Many people moved to Cahokia from other areas, which helped the city grow so fast. These new residents brought different ideas and ways of building. For example, the common design of a mound next to a plaza might have come from the Coles Creek culture.

Cahokia had strong trade connections across North America between 1050 and 1150 CE. Special stone from southern Illinois was used to make hoes, which were important tools for farmers. Cahokia helped control the distribution of these tools. Pottery and stone tools in the Cahokian style have been found far away, like in Minnesota. Materials from Pennsylvania, the Gulf Coast, and Lake Superior have been found at Cahokia.

During the Stirling phase (1100–1200 CE), Cahokia was at its most powerful. Religion played a big role in keeping the city's leaders in power. Important ceremonies, like those at Mound 72, helped bring people together. At Mound 72, archaeologists found the remains of many people, including important leaders buried with valuable items. Some burials suggest ritual practices were part of these ceremonies.

One challenge for large cities like Cahokia was getting enough food, especially during droughts. Also, dealing with waste from so many people could make the city unhealthy. Some believe Cahokia needed to attract new people constantly because of a high death rate.

Why Cahokia Declined

By the late 12th century, Cahokia began to change and decline. Around 1160–1170 CE, a large walled area in East St. Louis was burned down. This might have been due to problems or disagreements within the city. Later, around 1175 CE, people built a large wooden fence, called a palisade, around the center of Cahokia.

People started leaving the city in larger numbers in the late 12th century. By the mid-13th century, Cahokia's population had dropped by half or more. By 1350 CE, the city was abandoned.

Many things might have caused Cahokia's decline.

- Environmental changes: Some scholars think overuse of resources, like cutting down too many trees, or changes in climate, like more floods or droughts, played a role. However, recent research suggests there isn't strong evidence of human-caused erosion or flooding.

- Social and political issues: Different groups of people living in Cahokia might have had trouble getting along. This could have made it harder to have a strong, unified city. Also, leaders might have lost some of their power.

- Warfare: The palisade around Cahokia's center, with its protective towers, suggests there might have been threats from outside groups. Other burned villages in the area also point to rising tensions.

- Health problems: Living in a crowded city could lead to diseases. Also, relying heavily on corn without proper preparation could cause health issues like pellagra.

It's likely that a combination of these factors led people to leave Cahokia.

Abandonment and Later History

When Cahokia was abandoned, many other areas around it also became empty. This region is sometimes called "the Vacant Quarter." From 1400 to 1600 CE, there were no major settlements at Cahokia or in the wider region.

However, archaeologists found that the population in the greater area bounced back after 1400 CE. It reached a peak around 1650 CE before declining again.

The Dhegihan migration of some Native American groups also played a part in the changes in the region. Many modern Native American communities see Cahokia as part of their heritage. For example, the Ponca people have oral traditions about their ancestors living in a city they called "P’ahé’žíde" (red hill), which might refer to Cahokia.

After the city was abandoned, Algonquian peoples moved into the area in the mid-1600s. The Cahokia tribe was one of these groups, and that's how the site got its current name.

In the 18th century, French families claimed the land. In the 19th century, Trappist Monks lived on the grounds for a short time. Later, the Ramey family farmed the land. This is when people from Europe and America started to become very interested in understanding the site.

Cahokia Today

Native American Connections

Cahokia was one of the most important cities in North American history. Many Native American peoples and tribes today recognize the site as important to their heritage. The Osage Nation works closely with archaeologists and the site's managers. They even bought Sugarloaf Mound, one of the few remaining mounds in St. Louis, to protect it.

Many Indigenous groups, like the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Muscogee-Creek, continue mound-building traditions similar to those at Cahokia. Native American people still consider the site sacred. They visit to perform ceremonies and dances. Cahokia has also inspired much Native American art. For example, artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith created works inspired by the site.

Cahokia Museum and Interpretive Center

The Cahokia Museum and Interpretive Center is a place where visitors can learn about the ancient city. It welcomes up to a million visitors each year. The building, which opened in 1989, has won several awards for its design.

Studying Cahokia

Cahokia has been a place of interest for scientists and researchers for a long time. Since the 1960s, universities have studied the site, looking at everything from geology to archaeology. Timothy Pauketat is one of the most well-known archaeologists who has researched Cahokia for many years. Warren Wittry was also important in finding the Cahokia Woodhenge.

Protecting the Site

The state of Illinois first protected Cahokia Mounds in 1923. Later, it became a state historic site. In the 1950s, new highways threatened the site, but this also led to more funding for urgent archaeological digs. These investigations helped us understand how important the site is.

On July 19, 1964, Cahokia Mounds was named a National Historic Landmark. Then, on October 15, 1966, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1982, UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) named Cahokia Mounds a World Heritage Site. It's the only such site in Illinois and one of 24 in the United States. This special designation helps protect the site and brings in money for research.

Farming at Cahokia

Cahokia was surrounded by rich farmland. People used to think that corn (maize) was the main food source and helped the city grow. However, newer research suggests that Cahokian diets were quite varied, especially in the city's early days. They grew and ate many different crops, including goosefoot and sumpweed. Some people who had recently moved to Cahokia might have continued to hunt and gather, eating less corn.

People living in the city center seemed to have more diverse diets. Those in the outer areas relied more on corn. Some think that eating a lot of corn might have been linked to a lower social status in Cahokia.

The effect of Cahokian farming on the environment and its role in the city's decline is still debated. Some believe that the soil around Cahokia became worn out, leading to less food. However, others argue that because Cahokians used hand tools, their farming was less damaging to the soil than modern plows. This means the soil might have stayed healthy for a long time.

Historians note that Cahokia's peak happened during a warm period called the Medieval Warming Period. This period helped farming grow in North America, as crops like corn, beans, and squash were developed for cooler climates. The city's decline happened around the time of the Little Ice Age.

Amazing Features of Cahokia

The original site had 120 earthen mounds over 6 square miles. Today, 80 mounds remain. To build them, thousands of workers spent decades moving over 55 million cubic feet of earth in woven baskets. Monks Mound, for example, covers 14 acres, rises 100 feet high, and had a huge building on top.

City Layout

Early in its history, Cahokia had a huge building boom. A main city plan was created, with the city oriented towards the four main directions (north, south, east, west). Monks Mound was near the center. Four large plazas were built around Monks Mound.

South of Monks Mound is the Grand Plaza. This huge area covered about 50 acres and was over 1,600 feet long. At first, people thought this flat area was natural, but studies show it was carefully leveled and filled by the city's builders. It was used for big ceremonies and games, like chunkey. In this game, players rolled a disc-shaped stone and threw spears to where they thought it would land.

A main ceremonial path, called the Rattlesnake Causeway, connected the central area to a large burial mound to the south. This path was about 18 meters (59 feet) wide and 800 meters (2,600 feet) long. It was built slightly elevated over a swampy area. It might have been seen as a symbolic "Path of Souls."

The important central part of Cahokia was surrounded by a 2-mile-long wooden fence, or palisade, with protective towers. This palisade was added later and cut through some existing neighborhoods. Archaeologists found evidence that it was rebuilt several times, suggesting it was mainly for defense.

Beyond Monks Mound, there were as many as 120 other mounds. Today, 109 mounds have been found, with 68 inside the park. The mounds are of three types: platform, conical, and ridge-top. Each type likely had a different meaning and use.

Homes and Buildings

Cahokian homes were grouped together in planned areas around plazas and mounds. These clusters might have been for different religious or ethnic groups. Cahokia's neighborhoods had standard buildings, including steam baths, meeting houses, and temples.

Most Cahokian homes were made of poles and thatch, with rectangular shapes. Instead of single posts, they often used trenches for the walls.

Some researchers believe that up to 20 percent of Cahokia's neighborhood buildings were not homes. Instead, they might have been used for religious activities, connecting with spiritual beings. These buildings could be similar to "shaking tents" or "medicine lodges" from other Native American cultures.

Monks Mound

Monks Mound is the biggest structure and the heart of the city. It's a massive platform mound with four levels, standing 10 stories tall. It's the largest man-made earthen mound north of Mexico. Facing south, it is 100 feet high, 951 feet long, and 836 feet wide, covering 13.8 acres. It contains about 814,000 cubic yards of earth. The mound was built taller and wider over several centuries, in many different stages.

Monks Mound was named after a group of Trappist monks who lived there for a short time after European settlers arrived. Digs on top of Monks Mound found evidence of a large building. This was likely a temple or the home of the main chief, visible from all over the city. This building was about 105 feet long and 48 feet wide, and could have been as tall as 50 feet.

Mound 72

During excavations at Mound 72, a ridge-top burial mound, archaeologists found the remains of about 270 people. One important burial, known as the Beaded Burial or Birdman, was of a man laid on a bed of 10,000 marine-shell beads shaped like a falcon. This falcon warrior image is common in Mississippian culture. Near this man, a collection of finely made arrowheads from different regions was found, showing Cahokia's wide trade network.

Archaeologists found more than 250 other skeletons in Mound 72. Many of these burials suggest ritual practices. For example, there was a mass burial of over 50 young women and another mass burial of 40 men and women. The wood found in the mound has been dated to between 950 and 1000 CE.

Excavations showed that Mound 72 was not built all at once. It started as a series of smaller mounds that were later reshaped and covered to create its final ridge-top form.

Copper Workshop

Between 2002 and 2010, excavations near Mound 34 uncovered a copper workshop. This was a unique discovery, first found in the 1950s but then lost for 60 years. It's the only known copper workshop at a Mississippian culture site. The area had remains of tree stumps that might have held anvil stones. Analysis showed that the copper was heated and cooled repeatedly, a technique called annealing, similar to how blacksmiths work iron.

Artists here made religious items, like special masks and ceremonial earrings. Many beautiful Mississippian copper plates found at other sites, like Moundville and Etowah, are thought to have been made in Cahokia in the 13th century.

Cahokia Woodhenge

The Cahokia Woodhenge was a series of large circles made of timber posts. They were located about 850 meters (2,789 feet) west of Monks Mound. These circles are believed to have been built between 900 and 1100 CE. Each new circle was larger than the last.

The site was discovered in the early 1960s during highway construction. Archaeologist Dr. Warren Wittry found unusual, large post holes. When plotted, these holes formed arcs. Wittry realized they could be full circles and called them "woodhenges," like the famous sites in England.

The original wooden posts left dark stains in the soil as they decayed. This allowed researchers to find where the posts once stood. More excavations confirmed five separate timber circles, named Woodhenges I through V. In 1985, a reconstruction of Woodhenge III was built using the original post locations. This circle has 48 posts and a central post. It has been used to study how Cahokians might have tracked the sun and stars. The Illinois Historic Preservation Division hosts public sunrise observations at the spring and fall equinoxes and the summer and winter solstices.

Greater Cahokia

Cahokia was part of a larger group of connected sites, including East St. Louis, St. Louis Mounds, Janey B. Goode, and the Mitchell site. This whole area is often called "Greater Cahokia" because all these places were linked together.

Other Mounds Nearby

Until the 1800s, similar mounds existed in what is now St. Louis, about 8 miles west of Cahokia. Most of these mounds were flattened as St. Louis grew, and their earth was used for building.

One mound that still exists is Sugarloaf Mound. It's on the west bank of the Mississippi River. The base of another possible mound is in O'Fallon Park in St. Louis.

Another large Mississippian site is Kincaid Mounds State Historic Site in southern Illinois. It's about 140 miles southeast of Cahokia, in the Ohio River floodplain. With 19 mounds, it's the fifth-largest Mississippian site by number of monuments. It's believed to have been a powerful center, and it's also a National Historic Landmark.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Cahokia para niños

In Spanish: Cahokia para niños

- American Bottom

- Hopewell tradition

- Mississippian culture

- List of Mississippian sites

- Mississippian Ideological Interaction Sphere

- Mississippian stone statuary

- Poverty Point – A UNESCO-designated mound complex in Louisiana.

- Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks – A UNESCO-designated mound complex in Ohio.

- List of World Heritage Sites in the United States