Poverty Point facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Poverty Point National Monument |

|

|---|---|

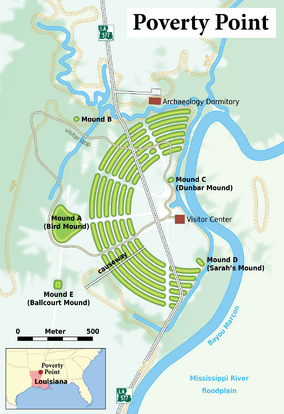

A map of the Poverty Point site

|

|

| Location | West Carroll Parish, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Nearest city | Epps, Louisiana |

| Area | 910.85 acres (368.61 ha) |

| Authorized | October 31, 1988 |

| Governing body | Louisiana Office of State Parks |

| Website | Poverty Point National Monument |

| Official name: Monumental Earthworks of Poverty Point | |

| Type: | Cultural |

| Criteria: | iii |

| Designated: | 2014 (38th session) |

| Reference #: | 1435 |

| Region: | Europe and North America |

Poverty Point State Historic Site/Poverty Point National Monument is an amazing place in northeastern Louisiana. It has huge earthworks built by ancient Native Americans. These people lived there between 1700 and 1100 BCE. They are known as the Poverty Point culture.

The culture spread across the Mississippi Delta and down to the Gulf Coast. The site is now a state historic site, a U.S. National Monument, and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It's a very important place!

Poverty Point is about 15.5 miles (25 km) from the Mississippi River. It sits on the edge of a raised area called Macon Ridge. The nearby town of Epps grew up much later.

Archaeologists think the site was a village, a trading center, or a special religious place. The name "Poverty Point" comes from a plantation that was on the land in the 1800s.

Contents

Exploring the Poverty Point Site

The Poverty Point site has many large earthworks. These include earthen ridges, mounds, and a big open area called a plaza. The main part of the site covers about 345 acres (140 ha). But the ancient settlement actually stretched for more than three miles (5 km) along the Bayou Macon.

The earthworks feature six curved ridges that form a C-shape. There are also several mounds both inside and outside these ridges. These unique concentric ridges are a special feature of Poverty Point.

Six Curved Ridges

The most striking part of the monument is its six C-shaped ridges. Each ridge is separated by a dip or a valley. Four pathways divide the ridges into different sections. Three other long ridges connect features in the southern part.

Today, the ridges are about 0.3 to 6 feet (10–185 cm) tall. They were likely taller long ago but have worn down from farming. The top of each ridge is 50 to 80 feet (15–25 m) wide. The valleys between them are 65 to 100 feet (20–30 m) wide.

The outermost ridge is about three-quarters of a mile (1.2 km) across. The innermost ridge is about three-eighths of a mile (0.6 km) across. These ridges are so big that their geometric shape was only clear from aerial photography. Scientists believe most of the ridges were built between 1600 and 1300 BCE.

The Central Plaza

Inside the innermost ridge is a large, flat area called the plaza. It covers about 37.5 acres (17.4 ha). Even though it looks natural, ancient people changed it a lot. They filled in low spots and added soil to raise the ground in some areas by over 3 feet (1 m).

In the 1970s, archaeologists found evidence of huge wooden posts in the western plaza. Later, special equipment showed several circular patterns underground. These circles were 82 to 206 feet (25–63 m) wide.

Further digging showed these circles were rings of large wooden posts. These post circles were built by Native Americans while the earthworks were still being made.

Mound A: The Bird Mound

Mound A is the biggest and most noticeable earthwork at the site. It is 72 feet (22 m) tall and about 705 by 660 feet (215 by 200 m) at its base. Mound A is west of the ridges. From above, it looks like a "T" shape. Some people think it looks like a bird or an "Earth island."

Scientists have learned that Mound A was built very quickly. It probably took less than three months! Before building, the area was burned. This burning happened between 1450 and 1250 BCE. The builders then covered the burnt area with silt. After that, they quickly finished the main construction.

There are no signs that the mound was built in stages or that it weathered over time. This means it was built in one huge effort. Mound A contains about 8.4 million cubic feet (238,000 cubic meters) of dirt. This makes it the second-largest earthen mound in eastern North America. Only Monks Mound at Cahokia is bigger, but it was built much later.

The dirt for Mound A likely came from shallow pits nearby. The Poverty Point people carried dirt from these pits and other areas to build the mound.

Mound B: The First Mound

Mound B is north and west of the six ridges, about 2050 feet (625 m) north of Mound A. It is shaped like a cone, about 21 feet (6.5 m) tall. Its base is about 180 feet (55 m) wide.

Mound B was the very first earthwork built at Poverty Point, sometime after 1700 BCE. It was built in several steps. Archaeologists found charcoal, fire pits, and marks from posts inside the mound. They even found impressions of woven baskets in the dirt.

In the 1950s, a human bone was reported at the base of the mound. It was thought to be from a cremation. However, recent studies found no evidence of an ash layer. The bone's identification has also been questioned.

Mound C: The Eastern Mound

Mound C is inside the plaza area, near the eastern edge of Macon Ridge. It is 6.5 feet (2 m) tall and about 260 feet (80 m) long. Today, it is 80 feet (25 m) wide, but erosion has made it narrower on the eastern side.

A dip in the mound was likely caused by a wagon road from the 1800s. Dates from the mound suggest it was one of the earliest structures built at the site. Mound C is made of several thin layers of different soils. Small amounts of ancient trash between the layers show it was built over time. The top layer gave it its final dome shape.

Mound D: The Later Mound

Mound D is a rectangular earthwork with a flat top. Today, a historic cemetery from the Poverty Point Plantation is on top of it. This mound is about 4 feet (1.2 m) tall and 100 by 130 feet (30 by 40 m) at its base. It sits on one of the concentric ridges.

Evidence suggests that Mound D was built much later. It was likely built by the Coles Creek culture almost 2000 years after the Poverty Point people left. This evidence includes pottery from the Coles Creek culture found near and under the mound. Also, special tests on the soil show it was built during the Coles Creek period.

Mound E: The Ballcourt Mound

Mound E is sometimes called the Ballcourt Mound. This name comes from two shallow dips on its flat top. These dips reminded some archaeologists of playing areas, but there's no proof of actual games played there.

Mound E is 1330 feet (405 m) south of Mound A. It's a rectangular mound with rounded corners and a ramp on its northeast side. It is 13.4 feet (4 m) tall and 360 by 295 feet (110 by 90 m) at its base.

Studies show Mound E was built in five stages. Few artifacts were found, but some were made of special stone from far away. A piece of charcoal found at the base of the ramp suggests it was built sometime after 1500 BCE.

Mound F: The Newest Discovery

A sixth mound, Mound F, was found at Poverty Point in 2013. It is outside and northeast of the curved ridges. Mound F is about 5 feet (1.5 m) tall and 80 by 100 feet (24 by 30 m) at its base.

Charred wood from its base shows it was built sometime after 1280 BCE. This makes it the last Archaic mound added to Poverty Point.

Nearby Mounds: Lower Jackson and Motley

About 1.8 miles (2.9 km) south of Poverty Point is the Lower Jackson Mound. It's a cone-shaped mound, 10 feet (3 m) tall and 115 feet (35 m) wide at its base. For a long time, people thought it was built at the same time as Poverty Point.

However, modern dating shows Lower Jackson Mound was built much earlier, around 3900 to 3600 BCE. This is about 1500 years before the Poverty Point earthworks! Interestingly, Lower Jackson Mound is on the same north-south line as Poverty Point's Mounds E, A, and B.

About 1.2 miles (2.2 km) north of Poverty Point is the Motley Mound. It is 52 feet (16 m) tall and 560 by 410 feet (170 by 125 m) at its base. Motley Mound looks a bit like Mound A. However, we don't know for sure which ancient culture built it.

How Poverty Point Was Built

Poverty Point was not built all at once. It was created by many generations of people over a long time. We don't know the exact order or timeline for building each earthwork. But studies suggest construction started as early as 1800 BCE and continued until about 1200 BCE.

Archaeologists found that before building, workers leveled the land. They filled in ditches to create the flat plaza and surfaces for the mounds and ridges. The main building material was loess, a type of silt soil. Loess is easy to dig but can wash away in water. So, clay might have been used to cover the loess and protect it.

The earthworks were built by dumping basket loads of dirt. Then, workers filled in the spaces between the piles. These baskets could hold 30 to 50 pounds (14–23 kg) of dirt. This suggests that men, women, and even children helped with the construction.

We don't know how many people built Poverty Point. One archaeologist, Jon L. Gibson, suggested that if 100 people worked six or seven days a month, it could have been built in a century by three generations. He also thinks workers might have lived on the site in temporary homes.

Some digs have found signs of long-term living on the ridges. This includes different layers of domestic activity over time.

Changes in weather, like more rain and floods, might have made it hard to live at Poverty Point. This could have led to the site being abandoned. This time marks a shift between the Archaic and later Woodland periods.

Why Was Poverty Point Built?

Archaeologists have long wondered about the purpose of Poverty Point. Was it a permanent settlement or a place for occasional gatherings? Some think houses were built on the ridges. They found postholes, hearths, and ovens, which suggest buildings and daily life.

Other archaeologists believe that if people lived there all the time, there would be more postholes. However, farming in later years might have destroyed some of these. Also, only small parts of the site have been dug up.

Some experts, like Sherwood Gagliano, think Poverty Point was a meeting place for groups to trade. But Jon Gibson believes there's too much ancient trash for it to be only an occasional meeting spot. He also thinks it would be too much work to build such a huge site just for trading.

Some archaeologists see religious meaning in Poverty Point. William Haag, who dug at the site in the 1970s, thought the pathways dividing the ridges lined up with the solstices (the longest and shortest days of the year). However, another astronomer, Robert Purrington, thinks the alignments were more about geometry than astronomy.

Researchers also look at Native American beliefs for clues. Gibson believes the ridges were built with their curves facing west. This might have been to keep bad spirits away from the complex.

The Poverty Point People

The people who built Poverty Point were hunter-fisher-gatherers. This means they found their food by hunting, fishing, and gathering plants. They were not farmers. This is special because most other ancient monuments, like Stonehenge or the Great Pyramid at Giza, were built by farming societies. Farming allowed more people to live together and build big things.

The Poverty Point people were Native Americans. They were descendants of people who came to North America thousands of years ago. They had their own unique way of life, different from other groups in the Lower Mississippi Valley. Because there are no written records, we can't connect them to any specific modern Native American tribe.

Their food came from local animals and plants. They ate deer and smaller animals like possums. They also ate various fish, turtles, shellfish, nuts, fruits, berries, and water plants. They had a wide variety of foods because different things were available in different seasons.

Tools and Artifacts

Most of the artifacts found at Poverty Point are small, baked clay shapes. These are called "Poverty Point Objects" or PPOs. They come in many forms. Archaeologists believe these fired clay objects were used for cooking. When placed in earth ovens, they held heat well and helped cook food.

The people of Poverty Point made some pottery. They created different types, some with plant fibers or crushed pottery mixed in. They also decorated their pottery with designs. However, they often traded for stone bowls made of steatite (soapstone) from the Appalachian Mountains.

Most tools seem to have been made right at the site. There's a lot of leftover material from tool-making on the ridges. Studies show that different parts of the site were used for different activities. For example, the north section was good for making tools. The south sections were where finished tools were used. Beads and pendants were mostly found in the west section. Clay figurines, however, were found all over the ridges.

Artifact styles also changed over time. For instance, cylindrical grooved PPOs were made earlier, and biconical (two-cone-shaped) ones came later.

There is no natural stone at Poverty Point. So, archaeologists know the people traded with other Native Americans for stone. Many tools were made from stone found in the Ouachita and Ozark mountains, and the Ohio and Tennessee river valleys. They also traded for soapstone from Alabama and Georgia, and galena (a lead ore) from Missouri and Iowa.

It was once thought that copper artifacts came from the Great Lakes region. But modern tests show some copper came from the southern Appalachian Mountains, the same place as the soapstone.

Discovering and Protecting Poverty Point

How Poverty Point Was Found

In the 1830s, an explorer named Jacob Walter was looking for lead ore. He stumbled upon Poverty Point and wrote about it in his diary. He described finding many pieces of ancient pottery and baked clay balls (PPOs). He also saw a huge mound, which was Mound A.

The first published description of the site was in 1873 by Samuel Lockett. In the early 1900s, archaeologists became very interested. Many experts studied and described the site, including Clarence B. Moore, Gerard Fowke, Clarence H. Webb, and Michael Beckman.

Major excavations happened in the 1950s by James A. Ford and Clarence Webb. Their work led to an important book about Poverty Point in 1956. Digging and research have continued into the 21st century. Scientists use tools like magnetic surveys to learn more about the plaza and ridges. The Louisiana Division of Archaeology also has a program to oversee and conduct research at the site.

Visiting Poverty Point Today

In 1960, an archaeologist named John Griffin suggested that Poverty Point become a national monument. At first, the government was worried about buying the land. But in 1962, it was named a National Historic Landmark.

In 1972, the State of Louisiana bought 400 acres (1.6 km2) of the site. In 1976, it opened to the public as the Poverty Point State Commemorative Area. The state built a museum to explain the earthworks and show the artifacts found there. In 1988, the U.S. Congress officially made it a U.S. national monument.

Poverty Point National Monument is open daily from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. It is closed on Thanksgiving, Christmas Day, and New Year's Day. Since the Louisiana Office of State Parks manages it, a National Parks pass is not accepted for entry. Louisiana also works with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to help control erosion at the site.

In 2013, Louisiana's Lieutenant Governor, Jay Dardenne, asked for emergency funding to stop erosion. This erosion, caused by Harlin Bayou, was threatening the ancient earthworks. The funding was approved to protect this important site.

A UNESCO World Heritage Site

In January 2013, the United States Department of the Interior nominated Poverty Point to be a UNESCO World Heritage Site. State Senator Francis C. Thompson said this was important not just for Louisiana, but for the whole world. He noted the cultural and economic benefits of having such a site.

On June 22, 2014, the UNESCO World Heritage Committee officially named Poverty Point a World Heritage Site. This happened at a meeting in Doha, Qatar. Lieutenant Governor Jay Dardenne sent a team to Qatar to help provide information about Poverty Point.

This designation made Poverty Point the first World Heritage Site in Louisiana. It was also the 22nd in the United States.

See also

In Spanish: Poverty Point para niños

In Spanish: Poverty Point para niños

- Mound Builders

- Marsden Mounds

- Toltec Mounds Archaeological State Park, in Arkansas

- Watson Brake

- LSU Campus Mounds

- National Register of Historic Places listings in West Carroll Parish, Louisiana

- Cahokia - UNESCO-designated mound complex in Illinois

- Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks - UNESCO-designated mound complex in Ohio

- Effigy Mounds National Monument - mound complex in Iowa

- List of national monuments of the United States

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Louisiana

- List of World Heritage Sites in the United States

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |