Carl Nielsen facts for kids

Carl August Nielsen (born June 9, 1865 – died October 3, 1931) was a famous Danish composer, conductor, and violinist. Many people think he is the most important composer from Denmark.

He grew up on the island of Funen with parents who loved music, even though they were poor. Carl showed his musical talent when he was very young. First, he played in a military band. Then, from 1884 to 1886, he studied at the Royal Danish Academy of Music in Copenhagen. His first important piece, the Suite for Strings, was played for the first time in 1888 when he was 23.

The next year, he joined the Royal Danish Orchestra as a second violinist. He played there for 16 years, performing in famous operas like Giuseppe Verdi's Falstaff and Otello when they first came to Denmark. Later, in 1916, he started teaching at the Royal Danish Academy. He continued to work there until he passed away.

Even though his music is now famous around the world, Carl Nielsen faced many challenges in his life. These struggles often showed up in his music. For example, some of his works from 1897 to 1904 are called his "psychological" period. This was partly because of difficulties in his marriage to the sculptor Anne Marie Carl-Nielsen.

Nielsen is especially known for his six symphonies, his Wind Quintet, and his concertos for violin, flute, and clarinet. In Denmark, his opera Maskarade and many of his songs are a big part of the country's culture.

His early music was inspired by composers like Brahms and Grieg. But soon, he created his own unique style. He experimented with new ways of using musical keys, moving away from the usual rules of composition. His last symphony, Sinfonia semplice, was written in 1924–25. He died six years later and is buried in Vestre Cemetery in Copenhagen.

During his lifetime, Nielsen was seen as a bit of an outsider in music. His works became much more popular around the world starting in the 1960s, thanks to conductors like Leonard Bernstein. In 2006, the Danish Ministry of Culture listed four of his works among the greatest pieces of Danish classical music. For many years, his picture was on the Danish hundred-kroner banknote. The Carl Nielsen Museum in Odense tells the story of his life and his wife's. Between 1994 and 2009, the Royal Danish Library created the Carl Nielsen Edition. This free online collection has information and sheet music for all of Nielsen's works.

Contents

Life

Growing Up

Carl Nielsen was born on June 9, 1865. He was the seventh of twelve children in a poor farming family. His home was in Sortelung, near Nørre Lyndelse, on the island of Funen. His father, Niels Jørgensen, was a house painter and a traditional musician. He played the fiddle and cornet very well and was often asked to play at local parties.

Nielsen wrote about his childhood in his book My Childhood on Funen. He remembered his mother singing folk songs. One of his uncles, Hans Andersen, was also a talented musician. Carl remembered starting music: "I had heard music before, heard father play the violin and cornet, heard mother singing, and, when in bed with the measles, I had tried myself out on the little violin."

He got his first violin from his mother when he was six. He studied violin and piano as a child. He wrote his first songs when he was eight or nine, including a lullaby and a polka. His parents did not think he would become a musician. So, when he was fourteen, they sent him to work for a shopkeeper. But the shopkeeper went out of business, and Carl had to go home.

After learning to play brass instruments, he joined the army band in Odense on November 1, 1879. He played the bugle and alto trombone. Even in the army, Nielsen kept playing the violin. He would play at dances with his father when he went home. The army paid him a small amount of money and bread, which later increased a little. This allowed him to buy clothes to play at barn dances.

Studies and Early Career

In 1881, Nielsen started taking violin lessons seriously. He studied with Carl Larsen, who worked at Odense Cathedral. We don't know how much music Nielsen wrote then. But he did write some pieces for brass instruments. He found it hard to understand how brass instruments were tuned in different keys.

He met Niels Gade, the director of the Royal Danish Academy of Music in Copenhagen. Gade liked Nielsen's music. So, Nielsen left the military band and started studying at the Academy in 1884. He was not the best student, but he learned a lot. He became good at violin with Valdemar Tofte. He also learned music theory from Orla Rosenhoff, who helped him a lot as a young composer. He studied composition with Gade, whom he liked as a friend.

Nielsen also made important friends with other students and families in Copenhagen. Because he grew up in the countryside, he was very curious about art, philosophy, and beauty. He left the Academy at the end of 1886. He then stayed with a retired merchant and his wife in Odense. There, he fell in love with their 14-year-old daughter, Emilie Demant. Their relationship lasted for three years.

On September 17, 1887, Nielsen played the violin at the Tivoli Concert Hall. His piece Andante tranquillo e Scherzo was played for the first time. Later, on January 25, 1888, his String Quartet in F major was performed. Nielsen thought this quartet was his official start as a professional composer. But his Suite for Strings, played at Tivoli Gardens on September 8, 1888, made a much bigger impression. This piece became his first official work, Op. 1.

By September 1889, Nielsen was good enough at the violin to join the Royal Danish Orchestra. This was a very respected orchestra at Copenhagen's Royal Danish Theatre. He played second violin under the conductor Johan Svendsen. He performed in the first Danish shows of Verdi's Falstaff and Otello. This job sometimes made Nielsen frustrated, but he stayed until 1905. After Svendsen retired in 1906, Nielsen became a conductor more often. He was officially made assistant conductor in 1910.

Before this job, he earned money by giving private violin lessons. He also had help from his supporters, like Jens Georg Nielsen and factory owners Albert Sachs and Hans Demant. After less than a year at the Royal Theatre, Nielsen won a scholarship. This money allowed him to travel around Europe for several months.

Marriage and Family

While traveling, Nielsen learned about and then disliked Richard Wagner's operas. He heard many top orchestras and soloists in Europe. He formed strong opinions on music and art. He loved the music of Bach and Mozart. But he was not sure about much of the music from the 1800s. In 1891, he met the composer and pianist Ferruccio Busoni in Leipzig. They wrote letters to each other for over thirty years.

In March 1891, Nielsen met the Danish sculptor Anne Marie Brodersen in Paris. She was also traveling on a scholarship. They traveled through Italy together and got married in Florence on May 10, 1891. Then they returned to Denmark. Their relationship was not just about love; they were also very similar in their thinking. Anne Marie was a talented artist. She was a strong and modern woman who wanted to have her own career. This goal sometimes caused problems in their marriage. Anne Marie would be away from home for months in the 1890s and 1900s. Carl was left to raise their three young children while also composing and working at the Royal Theatre.

Nielsen put his feelings about his marriage into his music. This was especially true between 1897 and 1904, a time he called his "psychological" period. During this time, he became very interested in what drives human personality. This led to his opera Saul and David, his Second Symphony (called The Four Temperaments), and the cantatas Hymnus amoris and Søvnen. Carl thought about getting a divorce in March 1905. He even thought about moving to Germany for a fresh start. But even with long periods apart, the Nielsens stayed married until he died.

Nielsen had five children, two of whom were born before his marriage to Anne Marie. He had a son, Carl August Nielsen, in January 1888. In 1912, another daughter, Rachel Siegmann, was born. Anne Marie never knew about her. With his wife, Nielsen had two daughters and a son. His older daughter, Irmelin, studied music theory with him. In 1919, she married Eggert Møller, a doctor who became a professor. His younger daughter, Anne Marie, became an artist. In 1918, she married the Hungarian violinist Emil Telmányi. He helped make Nielsen's music known as both a violinist and a conductor. Nielsen's son, Hans Børge, had a disability from meningitis and lived most of his life away from the family. He died in 1956.

Later Years as a Composer

At first, Nielsen's music was not well-known enough for him to support himself. When his First Symphony was played for the first time on March 14, 1894, Nielsen himself was playing in the second violin section. The symphony was a big success when it was played in Berlin in 1896. This helped his reputation grow a lot. He was asked more and more to write music for plays and special events. This gave him extra money.

Nielsen's cantata Hymnus amoris (Hymn of Love) was first performed on April 27, 1897. He was inspired to write it after seeing Titian's painting Miracle of the Jealous Husband during his honeymoon in Italy. On one copy, he wrote: "To my own Marie! These tones in praise of love are nothing compared to the real thing."

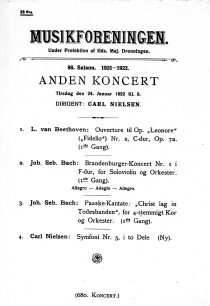

Starting in 1901, Nielsen received a small amount of money from the government each year. This money grew over time. It allowed him to stop giving private lessons and have more time to compose. From 1903, he also received money from his main music publisher, Wilhelm Hansen. Between 1905 and 1914, he was the second conductor at the Royal Theatre. He wrote his Violin Concerto, Op. 33 (1911), for his son-in-law, Emil Telmányi. From 1914 to 1926, he conducted the Musikforeningen orchestra. In 1916, he began teaching at the Royal Danish Academy of Music in Copenhagen. He worked there until his death.

The stress of having two careers and being away from his wife often led to problems in his marriage. The couple started separation procedures in 1916 and were officially separated by mutual agreement in 1919. From 1916 to 1922, Nielsen often lived on Funen or worked as a conductor in Gothenburg. This was a difficult time for Nielsen creatively. It happened during World War I, and it strongly influenced his Fourth (1914–16) and Fifth symphonies (1921–22). Many people think these are his greatest works. Nielsen was especially upset in the 1920s when his publisher could not print many of his important works, like Aladdin and Pan and Syrinx.

His sixth and final symphony, Sinfonia semplice, was written in 1924–25. After a serious health issue in 1925, Nielsen had to slow down. But he kept composing until he died. His sixtieth birthday in 1925 was celebrated with many congratulations, an award from the Swedish government, and a special concert in Copenhagen.

Final Years and Death

Nielsen's last big orchestral works were his Flute Concerto (1926) and the Clarinet Concerto (1928). Robert Layton, a music expert, said about the Clarinet Concerto: "If ever there was music from another planet, this is surely it." Nielsen's very last piece of music, the organ work Commotio, was played for the first time after he died in 1931.

In his last years, Nielsen wrote a short book of essays called Living Music (1925). In 1927, he wrote his memoir Min Fynske Barndom (My Childhood on Funen). In 1926, he wrote in his diary: "My home soil pulls me more and more like a long sucking kiss. Does it mean that I shall finally return and rest in the earth of Funen? Then it must be in the place where I was born: Sortelung, Frydenlands parish."

But this did not happen. Nielsen was admitted to Copenhagen's National Hospital on October 1, 1931, after several heart problems. He passed away there shortly after midnight on October 3. His family was with him. His last words to them were "You are standing here as if you were waiting for something."

He was buried in Copenhagen's Vestre Cemetery. All the music at his funeral, including the hymns, was his own work. After his death, his wife was asked to create a monument for him in central Copenhagen. She wanted to sculpt a winged horse, a symbol of poetry, with a musician on its back. He would be blowing a pipe over Copenhagen. There were disagreements about her design and not enough money. So, Anne Marie herself ended up paying for part of it. The Carl Nielsen Monument was finally shown to the public in 1939.

Music

Nielsen's works are sometimes known by CNW numbers. These numbers come from the Catalogue of Carl Nielsen's Works (CNW), which was published online in 2015. This new catalogue is meant to replace the older one from 1965 (FS numbers).

Musical Style

The music critic Harold Schonberg said that Nielsen's music is very broad, with strong rhythms and rich sounds. He also noted Nielsen's unique style. He compared Nielsen to Jean Sibelius, saying Nielsen had "just as much sweep, even more power, and a more universal message." Daniel M. Grimley, a music professor, called Nielsen "one of the most playful, life-affirming, and awkward voices in twentieth-century music." This is because of the beautiful melodies and lively harmonies in his work. Anne-Marie Reynolds, who wrote a book about Nielsen's songs, said that his song-writing greatly influenced his growth as a composer.

In Denmark, people see Nielsen and his music differently than people outside Denmark. His interest in folk music was very important to Danes. This became even more true during the national movements of the 1930s and World War II. During the war, singing was a way for Danes to show they were different from their German enemies. Nielsen's songs are still a big part of Danish culture and education.

Outside Denmark, Nielsen is mostly known for his orchestral music and the opera Maskarade. But in Denmark, he is more of a national symbol. In 2006, the Danish Ministry of Culture officially brought these two sides together. They listed twelve great Danish musical works, including Nielsen’s opera Maskarade, his Fourth Symphony, and two of his Danish folk songs.

Nielsen himself had mixed feelings about late Romantic German music and nationalism in music. In 1909, he wrote to another composer, saying he thought German music was becoming too complicated. He believed music should go back to being "pure and clear." But in 1925, he also wrote: "Nothing destroys music more than nationalism does... and it is impossible to deliver national music on request."

Nielsen carefully studied old polyphony from the Renaissance period. This influenced some of the melodies and harmonies in his music. His Tre Motetter (Three Motets) is a good example of this. To critics outside Denmark, Nielsen's early music sounded neo-classical. But it became more modern as he developed his own style. He often moved from one musical key to another, sometimes ending a piece in a different key than where it started. This can be heard in his symphonies. Some critics say his rhythms, or his use of certain musical notes, are typically Danish. Nielsen himself wrote: "The intervals, as I see it, are the elements which first arouse a deeper interest in music... [I]t is intervals which surprise and delight us anew every time we hear the cuckoo in spring."

Nielsen's ideas about music style can be summed up in his advice to a Norwegian composer in 1907: "You have... fluency, so far, so good; but I advise you again and again, my dear Mr. Harder; Tonality, Clarity, Strength."

Symphonies

Nielsen is perhaps most famous outside Denmark for his six symphonies. He wrote them between 1892 and 1925. These works share many things in common. They are all about 30 minutes long. Brass instruments are very important in them. They also have unusual changes in musical keys, which makes the music more dramatic.

His Symphony No. 1 (1890–92) shows Nielsen's unique style right from the start. It also shows influences from Grieg and Brahms. In Symphony No. 2 (1901–02), Nielsen explores different human personalities. He was inspired by a painting in an inn that showed the four temperaments (choleric, phlegmatic, melancholic, and sanguine).

The title of Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Espansiva (1910–11), means the "outward growth of the mind's scope." It uses Nielsen's technique of having two keys at the same time. It also has a peaceful part with soprano and baritone voices singing a tune without words. Symphony No. 4, The Inextinguishable (1914–16), was written during World War I. It is one of his most often played symphonies. In the last part, two sets of timpani drums are placed on opposite sides of the stage, playing a kind of musical fight. Nielsen said the symphony was about "the life force, the unquenchable will to live."

The Symphony No. 5 (1921–22) is also played often. It shows another battle between order and chaos. A snare drummer is told to interrupt the orchestra, playing freely and out of time, as if trying to destroy the music. When the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra played it in 1950, it caused a big stir. This helped make Nielsen's music popular outside Scandinavia. His Symphony No. 6 (1924–25), called Sinfonia Semplice (Simple Symphony), has a similar musical language to his other symphonies. But it develops into a series of short musical scenes, some sad, some strange, and some funny.

Operas and Cantatas

Nielsen wrote two operas, and they are very different. The four-act Saul og David (Saul and David), from 1902, tells the Biblical story of Saul's jealousy of young David. On the other hand, Maskarade (Masquerade) is a funny opera in three acts from 1906. It is based on a comedy by Ludvig Holberg.

Saul and David did not get good reviews when it first played in November 1902. It did not do better when it was played again in 1904. But in November 1906, Masquerade was a huge success. It played 25 times in its first four months. It is seen as Denmark's national opera. In Denmark, it is still very popular because of its many songs, dances, and its old Copenhagen feel.

Nielsen wrote many choral works, but most were for special events and not played often. However, three full cantatas for singers, orchestra, and choir are still performed. Nielsen wrote Hymnus amoris (Hymn of Love), Op. 12 (1897), after studying old choral music. Critics praised its clarity and purity. But one reviewer thought it was too fancy to use Latin instead of Danish.

Søvnen (The Sleep), Op. 18, is Nielsen's second major choral work. It describes the different stages of sleep. Its middle part, with strange sounds, shows the terror of a nightmare. This shocked reviewers when it was first played in March 1905. Fynsk Foraar (Springtime on Funen), Op. 42, finished in 1922, is considered the most Danish of all Nielsen's pieces. It celebrates the beauty of Funen's countryside.

Concertos

Nielsen wrote three concertos. The Violin Concerto, Op. 33, is from 1911. It follows the traditional style of European classical music. But the Flute Concerto (1926) and the Clarinet Concerto, Op. 57 (1928), are later works. They were influenced by the modern music of the 1920s. According to music expert Herbert Rosenberg, they show "an extremely experienced composer who knows how to avoid inessentials."

Unlike his later works, the Violin Concerto has a clear, melody-focused structure. The Flute Concerto, which has two movements, was written for the flautist Holger Gilbert-Jespersen. He was part of the Copenhagen Wind Quintet, which had played Nielsen's Wind Quintet for the first time. The Flute Concerto shows the modern styles of the time. For example, the first movement changes between different musical keys. The flute then plays a beautiful, singing tune.

The Clarinet Concerto was also written for a member of the Copenhagen Wind Quintet, Aage Oxenvad. Nielsen pushed the instrument and player to their limits. The concerto has only one continuous movement. It shows a struggle between the solo clarinet and the orchestra, and between two main competing keys.

Nielsen called the way he wrote his wind concertos objektivering ("objectification"). This meant giving the musicians freedom to interpret and perform the music within the rules set by the score.

Orchestral Music

Nielsen's first work written specifically for orchestra was the very successful Suite for Strings (1888). It sounded like Scandinavian Romantic music, similar to Grieg and Svendsen. This piece was a big step for Nielsen. It was his first real success, and it was the first time he conducted one of his own pieces.

The Helios Overture, Op. 17 (1903), came from Nielsen's time in Athens. He was inspired to write a piece showing the sun rising and setting over the Aegean Sea. This piece is a showpiece for the orchestra and is one of Nielsen's most popular works. Saga-Drøm (Saga Dream), Op. 39 (1907–08), is a tone poem for orchestra based on the Icelandic Njal's Saga.

At the Bier of a Young Artist (Ved en ung Kunstners Baare) for string orchestra was written for the funeral of Danish painter Oluf Hartmann in January 1910. It was also played at Nielsen's own funeral. Pan and Syrinx, a lively nine-minute symphonic poem inspired by Ovid's Metamorphoses, was first played in 1911. The Rhapsodic Overture, An Imaginary Trip to the Faroe Islands (En Fantasirejse til Færøerne), uses Faroese folk tunes but also has parts that Nielsen composed freely.

Some of Nielsen's orchestral works for the stage include Aladdin (1919) and Moderen (The Mother), Op. 41 (1920). Aladdin was written for a play by Adam Oehlenschläger at The Royal Theatre in Copenhagen. The full music lasts over 80 minutes, making it Nielsen's longest work besides his operas. But a shorter orchestral suite, with the Oriental March, Hindu Dance, and Negro Dance, is often performed. Moderen was written to celebrate the joining of Southern Jutland with Denmark. It was first played in 1921 and uses patriotic poems written for the occasion.

Chamber Music

Nielsen wrote several chamber music pieces. Some of them are still very popular around the world. The Wind Quintet, one of his most famous pieces, was written in 1922 especially for the Copenhagen Wind Quintet. Robert Simpson explained that Nielsen loved wind instruments because he loved nature. He also said that Nielsen was very interested in human character. In the Wind Quintet, each part was carefully made to fit the personality of each musician.

Nielsen wrote four string quartets. The First String Quartet No. 1 in G minor, Op. 13 (1889, revised 1900), has a "Résumé" part at the end. This part brings together themes from the first, third, and fourth movements. The Second String Quartet No. 2 in F minor, Op. 5, came out in 1890. The Third String Quartet in E-flat major, Op. 14, was written in 1898. The music historian Jan Smaczny said that in this work, Nielsen handled the music with confidence. He wished Nielsen had written more string quartets.

The Fourth String Quartet in F major (1904) first received mixed reviews. Critics were not sure about its quiet style. Nielsen changed it several times. The final version from 1919 is listed as his Op. 44.

The violin was Nielsen's own instrument, and he wrote four big chamber works for it. The First Sonata, Op. 9 (1895), had sudden key changes and short themes. This confused Danish critics at its first performance. The Second Sonata, Op. 35, from 1912, was written for the violinist Peder Møller. He had played Nielsen's Violin Concerto for the first time earlier that year. This work is an example of Nielsen's progressive tonality. Even though it is said to be in G minor, the first and last movements end in different keys.

Two other works are for solo violin. The Prelude, Theme and Variations, Op. 48 (1923), was written for Telmányi. Like Nielsen's Chaconne for piano, it was inspired by the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. The Preludio e Presto, Op. 52 (1928), was written to celebrate the sixtieth birthday of composer Fini Henriques.

Keyboard Works

Even though Nielsen mainly composed at the piano, he only wrote directly for it sometimes over 40 years. His piano works often had a unique style, which made them slower to become popular internationally. Nielsen's own piano playing was probably not very good. John Horton, a critic, said about Nielsen's early piano pieces: "Nielsen's technical resources hardly measure up to the grandeur of his designs." But he called the later pieces "major works which can stand comparison with his symphonic music."

The Symphonic Suite, Op. 8 (1894), had an anti-romantic tone. A later critic called it "nothing less than a clenched fist straight in the face of all established musical convention." Nielsen said his Chaconne, Op. 32 (1917), was "a really big piece, and I think effective." It was inspired by Bach's music, especially the chaconne for solo violin. It was also influenced by piano versions of Bach's music by composers like Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms, and Ferruccio Busoni.

Also a large work from the same year is the Theme and Variations, Op. 41. Critics have seen influences of Brahms and Max Reger in it. Nielsen had once written to a friend that he was more sympathetic to Reger's efforts than to Richard Strauss.

All of Nielsen's organ works were written later in his life. The Danish organist Finn Viderø suggested that Nielsen became interested in organ music because of a movement to renew organ playing. Nielsen's last major work, Commotio, Op. 58, is a 22-minute piece for organ. He composed it between June 1930 and February 1931, just a few months before he died.

Songs and Hymns

Over the years, Nielsen wrote music for more than 290 songs and hymns. Most of them were for poems by famous Danish writers like N. F. S. Grundtvig and Ingemann. In Denmark, many of these songs are still popular today with both adults and children. They are seen as "the most representative part of the country's most representative composer's output."

Nielsen made a very important contribution to the 1922 book, Folkehøjskolens Melodibog (The Folk High School Songbook). He was one of the editors, along with Thomas Laub, Oluf Ring, and Thorvald Aagaard. The book had about 600 melodies. About 200 of them were written by the editors. It was meant to provide songs for communal singing, which was a big part of Danish folk culture. The collection was very popular and became part of the Danish education system.

During the German occupation of Denmark in World War II, large singing gatherings used these melodies. This was part of Denmark's "spiritual re-armament." After the war in 1945, one writer called Nielsen's contributions "shining jewels in our treasure-chest of patriotic songs." This is still a very important reason why Danes value the composer so much.

Editions

Between 1994 and 2009, a complete new edition of Nielsen's works, the Carl Nielsen Edition, was created. The Danish Government paid for it. For many of his works, including the operas Maskarade and Saul and David, and the full Aladdin music, this was the first time they were printed. Before this, people used copies of handwritten music for performances. Now, all the music scores can be downloaded for free from the website of the Danish Royal Library. The library also owns most of Nielsen's original music papers.

Legacy

From 1916, Nielsen taught at the Royal Academy. He became its director in 1931, shortly before he died. Earlier in his career, he also taught private students to earn more money. Because of his teaching, Nielsen had a big impact on classical music in Denmark. Some of his most successful students included composers like Thorvald Aagaard and Jørgen Bentzon. Other students were the music expert Knud Jeppesen, pianist Herman Koppel, and conductor Mogens Wöldike.

The Carl Nielsen Society keeps a list of performances of Nielsen's works around the world. This shows that his music is regularly played in many countries. His concertos and symphonies appear often on these lists.

The Carl Nielsen International Competition started in the 1970s. A violin competition has been held every four years since 1980. Flute and clarinet competitions were added later but have now stopped. An international Organ Competition, also in Odense, joined the Nielsen competition in 2009. But from 2015, it will be organized separately.

In Denmark, the Carl Nielsen Museum in Odense is dedicated to Nielsen and his wife, Anne Marie. The composer's picture was on the 100 kroner note from 1997 to 2010. His image was chosen because of his contributions to Danish music, like his opera Maskarade and his many songs.

Many special events were planned around June 9, 2015, to celebrate 150 years since Nielsen's birth. Besides many performances in Denmark, concerts were held in cities across Europe, Japan, Egypt, and New York. On June 9, the Danish National Symphony Orchestra played a concert in Copenhagen. It featured Hymnus amoris, the Clarinet Concerto, and Symphony No. 4. This concert was broadcast across Europe and the United States. The Danish Royal Opera performed Maskarade and a new show of Saul og David. The city of Odense, which has strong ties to Nielsen, had many concerts and cultural events for the anniversary year.

A small planet, 6058 Carlnielsen, is named after him.

See also

In Spanish: Carl Nielsen para niños

In Spanish: Carl Nielsen para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |