Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company facts for kids

| stagecoach | |

| Industry | transportation |

| Fate | bankrupt |

| Predecessor | Leavenworth City and Pike's Peak Express Company |

| Founded | February 13, 1860 in St. Joseph, Missouri, United States |

| Founders | Alexander Majors William Hepburn Russell William Bradford Waddell |

| Defunct | March 21, 1862 |

| Headquarters | 601 Montgomery Street, , |

|

Areas served

|

St. Joseph, Missouri, Denver, Salt Lake City |

| Owner | Ben Holladay |

| Subsidiaries | Pony Express |

The Central Overland California and Pike's Peak Express Company was a stagecoach company in the American West. It operated in the early 1860s. This company is most famous for being the parent company of the Pony Express.

It started as part of a larger freighting company called Russell, Majors, and Waddell. Two partners, Majors and Waddell, bought out Russell's earlier stage line. That first stage line made its initial trip from Westport, Missouri, to Denver on March 9, 1859.

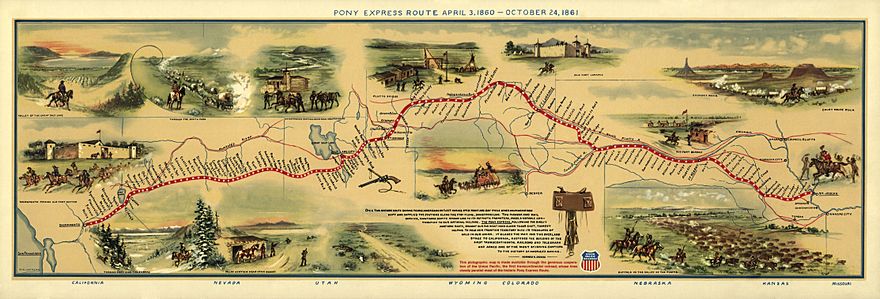

The company's stage lines ran from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Denver and Salt Lake City. In May 1860, it took over the mail delivery contract from Utah to California. To try and get a bigger contract from the U.S. government, the company launched the Pony Express. This fast mail service ran between St. Joseph and San Francisco, starting on April 3, 1860.

Running frequent stagecoach service and losing a lot of money on the Pony Express caused problems. When the Transcontinental Telegraph was finished, the Pony Express was no longer needed. The company ran out of money and was sold to Ben Holladay for $100,000.

Contents

Russell, Majors, and Waddell: A Big Business Partnership

As the United States grew westward in the early 1800s, the military built forts. These forts needed supplies. At first, the government hired many small companies to deliver goods. But this system became slow and difficult.

In 1854, a military leader named Thomas Jesup changed things. He decided to offer one big contract to supply most forts west of the Missouri River. This contract was worth a lot of money. It needed more resources than most small companies had.

Alexander Majors was one of the people who supplied military forts before 1854. He was known for successfully hauling goods along the Santa Fe Trail. William Bradford Waddell owned a store in Lexington, Missouri. He was known for being careful with money. In 1852, Waddell teamed up with William Hepburn Russell. Russell was a charming businessman who had some successes and wanted to be important in society.

In 1855, Waddell and Russell asked Majors to join them. They wanted to get the new military supply contract. Three months later, their new company, Russell, Majors, and Waddell, won a two-year contract. They would supply all military posts west of the Mississippi River.

How the Partners Divided the Work

The three partners split the work based on their skills. William Waddell handled the money and made sure the business ran smoothly. William Russell was the company's salesman. He got contracts from the government and dealt with banks for funding. Alexander Majors managed the freighting. This included hiring workers, overseeing loading, and making sure deliveries were on time.

The partners generally worked well together. Majors and Waddell were both careful with money. Russell was the opposite, but he often traveled to the East Coast to find new deals. Their company became the largest freighting business in western Missouri. They had almost all the contracts for moving goods in the West.

Challenges and Successes of the Company

The new government contract required a huge investment. They had to build warehouses, stables, and wagon shops. They also needed to hire and pay many workers, like wagon masters and teamsters. They bought oxen, wagons, and other equipment.

The way the three partners divided their work helped them succeed. Their experience in organizing this huge freighting business was very useful later on. In their first two years, 1855 and 1856, the company made a profit of $300,000. Russell, Majors, and Waddell grew their business. They bought land and opened new stores. Because they were so good at handling the military's freight, they won the next contract in February 1857.

In May 1857, a conflict called the Utah War began. The government sent 2,500 troops to Utah. Russell, Majors, and Waddell had to quickly gather more wagons. They needed to transport millions of pounds of military supplies. The company took out large loans to pay for this new expedition.

During the Utah War, they lost three wagon trains, worth over $125,000. They had already used up all their credit and were almost out of money. To make things worse, Congress delayed payment for the 1857 contract. Despite this, the War Department still needed supplies. The Secretary of War, John B. Floyd, personally promised they would be paid. This promise helped Russell, Majors, and Waddell get more credit to finance new supply trains.

Leavenworth City & Pike's Peak Express Company: The Gold Rush Connection

In July 1858, gold was found in Little Dry Creek. This was the first major gold discovery in the Rocky Mountains. It started the Pike's Peak Gold Rush. William H. Russell heard about the gold in Leavenworth, Kansas. He believed many people would move to the area.

Russell teamed up with John S. Jones, a former business partner. They found new investors and borrowed money. They started a stagecoach and express line to Denver. The new service was called the Leavenworth City & Pike's Peak Express Company. It carried "passengers, mail, freight, and gold" to and from the Pike's Peak area. The route followed a trail between the Republican and Smoky Hill rivers in Kansas.

Building the Route and Services

The new company mapped out a 687-mile route. They built 27 stations, bought new coaches and mules, and hired many workers. The first trip in March 1859 took 19 days. During this trip, they finished building the route. Later trips took as little as six days. A passenger ticket cost $100. Express packages cost $1.00 per pound, and letters cost 25 cents each.

The town of Denver gave 53 lots to the company. They celebrated the first arrival with a special newspaper edition. The coach returning to Leavenworth carried $3,500 worth of gold. This return trip was also celebrated with speeches and music.

Many people came to the Pike's Peak region, but few could afford the stagecoach. Most traveled on foot or horseback. Russell and Jones wanted to make more money by getting a government contract to deliver mail. On May 11, 1859, their company bought Hockaday & Company. This company had the postal contract between St. Joseph, Missouri, and Salt Lake City. Hockaday & Company had only a few light stagecoaches and seven stations. Their mail contract was profitable until the post office reduced payments.

Changing Routes and Financial Troubles

After combining the two companies, Russell and Jones changed their Denver coaches' route. They moved to Hockaday's more northern route. They had used their original route for less than six weeks. The new route went north to Fort Kearney. Then it turned south toward Denver at Julesburg. Traffic to Salt Lake City continued via Fort Laramie and Fort Bridger.

The route was split into three parts. The first part ran from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Julesburg. It had 19 stations. The second part went from Julesburg to South Pass. The third part ran from South Pass to Salt Lake City. The company built new stations every 16 to 40 miles. These stations offered rooms and food for passengers and barns for mules. Building new stations and abandoning old ones was very expensive for the company.

By the fall of 1859, the company was in deep debt. Employees weren't getting paid, stations ran low on supplies, and creditors were owed over $525,000. William H. Russell had not partnered with Alexander Majors or William Waddell in this new company. They thought it was too soon to know if the gold rush would last. However, Russell used the good reputation of Russell, Majors, and Waddell to get credit for his new company. This caused tension among the three partners, especially after their recent financial problems with military contracts.

Majors and Waddell knew that if Russell's company failed, it could also bring down Russell, Majors, and Waddell. So, on October 28, 1859, the three men formed a new partnership. This new company took on the assets and debts of the Leavenworth City & Pike's Peak Express Company. Less than a month later, Russell named the new firm the Central Overland California & Pike's Peak Express Company, or C.O.C. & P.P. Express Co. He hoped this new name would help him get a daily mail route to California through the Rocky Mountains.

Russell went to New York in December to raise money and deal with creditors. On January 27, 1860, he wrote to his son: "Have determined to establish a Pony Express to Sacramento, California, commencing 3rd of April. Time ten days."

Organizing the Pony Express: A Race Against Time

It's not entirely clear who first thought of the Pony Express idea. But it was Russell, Majors, and Waddell who made it happen. Russell wanted the Pony Express to start just over two months after forming the Central Overland California & Pike's Peak Express.

The company used its great organizing skills to build stations, prepare roads, get horses and equipment, and hire staff. They hired stationmasters, mail agents, and riders. Their goal was to open the route from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, California, on time. St. Joseph was the perfect starting point in the East because the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad ended there. This allowed for fast communication with the eastern states.

Setting Up the Route and Stations

The route was divided into five sections, each with its own manager. These sections ran from St. Joseph to Fort Kearny, Fort Kearny to Horseshoe station, Horseshoe Station to Salt Lake City, Salt Lake City to Roberts Creek, and Roberts Creek to Sacramento. The route followed the same roads as the stagecoach line. However, many roads needed repairs or upgrades for the new, faster mail service. Many existing stations were used for the Pony Express. But new stations were also built to make sure stations were only about 10 miles apart.

The company knew the trail between St. Joseph and Salt Lake City well. But the trail from Salt Lake City to Sacramento was mostly unknown. At the time, George Chorpenning had a federal mail contract for California and Utah. His service brought in $130,000 a year. He received mail in San Francisco by ship and then sent it to Salt Lake City twice a month. Chorpenning didn't want to share his resources. So, the C.O.C. & P.P. Express Co. had to build its own roads and stations.

The company started building along the Humboldt River in northern Nevada. But when government engineers found a new route across central Nevada, they switched. This new trail shortened the distance between Utah and California by about 150 miles. By December 1859, both Chorpenning's company and the C.O.C. & P.P. Express Co. were building stations along this new route.

Horses, Riders, and First Runs

The Central Overland California & Pike's Peak Express Company spent a lot of money building and equipping these new stations. This was despite the company's financial struggles. They bought between 400 and 500 horses. They hired almost 200 stationmasters and 80 riders. "Home stations," where a rider would rest before riding back, were placed every 75 to 100 miles. In April 1860, when the Pony Express started, between 119 and 153 stations were active.

The company's main office in San Francisco was at 601 Montgomery Street. Today, it's a California Historical Landmark. The company also had offices in big eastern cities like New York City and Washington D.C.. People could drop off mail there to be sent to California. On March 17, 1860, an advertisement announced "PONY EXPRESS — NINE DAYS FROM SAN FRANCISCO TO NEW YORK." Similar announcements followed in New York and St. Louis. It's estimated that the company spent over $70,000 to set up the service. Monthly expenses were about $5,000.

The first Pony Express run was planned for April 3, 1860. The mail pouch for the West missed a train connection. So, a special train had to deliver it to St. Joseph. The mail arrived two hours late. After some speeches, it set off for Sacramento. Seventy-five ponies were used for this first trip from Missouri to California. Each major city along the way celebrated as the rider passed through. On April 14, 1860, around 1 a.m., the Pony Express from St. Joseph arrived in San Francisco. The eastbound rider left San Francisco on April 3 and reached St. Josephs on April 13. The Pony Express was officially running!

Early Challenges and Successes

In its first month, Pony Express riders faced bad weather, tough land, and the physical challenge of riding up to 100 miles a day. Despite this, operations went smoothly. The number of letters sent wasn't enough to cover costs. However, many towns found the service valuable for the news the riders brought. There was even talk of other express companies starting up.

On May 11, 1860, Postmaster General Joseph Holt canceled George Chorpenning's mail contract. He offered it to the C.O.C. & P.P. Express Co. instead. This contract paid about $260,000 per year, enough to cover the Pony Express's costs.

In early May 1860, the Pyramid Lake War began after an event at Williams Station. For over three months, there were fights between white settlers and local Paiute people. Pony Express stations were often easy targets for raids. They were in remote places with supplies and few people. Because of lost staff, stations, and horses, the Pony Express had to stop operations between Carson Valley and Salt Lake City until the end of June.

The C.O.C. & P.P. Express Co. rebuilt the destroyed stations. They also placed up to five guards at each station along this part of the route. The Pony Express restarted service at the end of June. However, fighting between the Paiute and settlers continued until August.

During the almost two-month break, the Pony Express still rode between Salt Lake City and St. Joseph. But this route brought in little money. The C.O.C. & P.P. Express Co. spent over $75,000 to reopen the route to California. Much of this money went to making stations safer and hiring armed guards. The company was running low on funds. A bill was proposed in Congress to help pay for the Pony Express, but it didn't pass. As raids continued, Russell, Majors, and Waddell decided they would end the service in January 1861 if Congress didn't help.

However, the Post Office Department renewed their St. Joseph to Salt Lake City contract on October 28. Use of the Pony Express continued to grow through the end of the year. With more money coming in, the company decided to keep the Pony Express running, but with fewer trips during the winter.

The End of the Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company

As owners of the Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company, Russell, Majors, and Waddell were involved in everything. They set up and ran both the stagecoach lines and the Pony Express. At the same time, they continued their freighting business. This business delivered supplies to U.S. Army forts.

In late 1860, Russell, Majors, and Waddell still hadn't been paid for their 1857 contract. But with Secretary of War John B. Floyd's personal promises, they had taken on over $5,000,000 in debt. This was on top of the separate debt from setting up the C.O.C. & P.P. Express Co.

Financial Troubles and a Scandal

In March 1860, Russell, Majors, and Waddell prepared a group of wagons to take supplies to the Army. Due to unexpected problems, the wagons couldn't leave until late August. This delay was very costly. They still had to pay the men, house the wagons and supplies, and feed the animals. Much of the company's debt was due in mid-summer. They expected to pay it with money from the supply run. But the War Department would only pay once the goods were received. The company had to take out more loans, which further hurt their credit. If they could get a government contract for mail, worth $600,000 to $900,000 a year, their money problems would be solved.

The Pony Express was working well (though not making money). Also, the ocean mail service was ending in June 1860. So, a new mail contract looked promising. However, Congress ended its session without passing a bill for a central overland mail route. William Russell went to New York to raise more money but failed. He then met Godard Bailey, a relative of Secretary Floyd. Bailey might have worried that Floyd would have to resign if the company went bankrupt. So, Bailey agreed to help Russell get money.

Bailey let Russell use government security bonds from the Indian Trust Fund. Russell used these as collateral for more loans. Bailey did not own these bonds, and Russell offered a note in their place that he knew was worthless. This was a serious misuse of funds. Russell borrowed from the Indian Trust Fund three times. Eventually, Bailey felt guilty and confessed. Both men were arrested.

The start of the Civil War changed things, and they were not put on trial for this. However, the bond scandal ruined the reputation of Russell, Majors, and Waddell. Their freighting company soon went bankrupt. Even though Russell, Majors, and Waddell failed, the Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company was a separate business and kept operating.

The End of the Line

When Texas left the Union in 1861, they destroyed the Butterfield Overland Mail line. This cut off land communication from California to the East. The postmaster general couldn't just cancel the contract. So, Congress moved the route north to keep mail moving through the Union states. The C.O.C. & P.P. Express Co. supported this for several reasons. First, the government would help pay for the Pony Express until the telegraph reached California. Second, neither their company nor Overland Mail could afford to run the line alone.

So, the two companies made a deal. The C.O.C. & P.P. Express Co. would run the mail from St. Joseph to Salt Lake City. Overland Mail would run from Salt Lake City to California, using the C.O.C. & P.P. Express Co.'s facilities. This was a good development for the company, given its financial state at the start of the year.

With the Civil War underway, the Pony Express was the fastest way to send information between East and West. It was in high demand. But the telegraph was catching up quickly. It was moving east from California and west from Nebraska. By mid-August, news sent by telegraph to San Francisco arrived two days before the Pony Express riders. Despite this, the amount of express mail continued to grow.

However, once the Pony Express stopped getting government money after the transcontinental telegraph was finished, the business ran out of cash. Employees even called it "Clean Out of Cash and Poor Pay."

On April 26, 1861, Bela M. Hughes became the company's president. The Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company continued to deliver mail for the Overland Mail Company until its contract ended in 1862. At that point, Overland Mail offered the contract for bids, and Ben Holladay won it. On March 21, 1862, Holladay bought the C.O.C. & P.P. Express for $100,000. He made it part of his own company, the Overland Stage Company. With the company out of business, its old facilities in Kansas City, Missouri, eventually became the Kansas City Stockyards.

See also

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |