Church Rock uranium mill spill facts for kids

Quick facts for kids UNC Church Rock |

|

|---|---|

| Superfund site | |

United Nuclear Corporation Church Rock mill site after clean-up

|

|

| Geography | |

| City | Gallup, New Mexico |

| County | McKinley |

| State | New Mexico |

| Coordinates | 35°39′03″N 108°30′23″W / 35.65083°N 108.50639°W |

| Information | |

| CERCLIS ID | NMD030443303 |

| Contaminants | Metals, radionuclides |

| Responsible parties |

United Nuclear Corporation |

| Progress | |

| Proposed | December 30, 1982 |

| Listed | August 8, 1983 |

| Construction completed |

August 29, 1998 |

| List of Superfund sites | |

The Church Rock uranium mill spill happened in New Mexico, USA, on July 16, 1979. A dam at the United Nuclear Corporation's uranium mill in Church Rock broke. This dam held a pond of tailings, which are leftover waste materials from processing uranium.

This accident is still the largest release of radioactive material in U.S. history. It released more radioactivity than the Three Mile Island accident that happened just four months earlier.

The mill operated from 1977 to 1982. It was located about 17 miles (27 km) north of Gallup, New Mexico. The land around it was part of the Navajo Nation. When uranium ore was processed, it created a watery, acidic waste called tailings. This waste was pumped into the disposal pond.

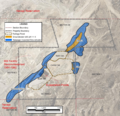

When the dam broke, it released over 1,100 tons (1,000 metric tons) of solid radioactive waste. It also released about 94 million gallons (356 million liters) of acidic, radioactive liquid. This spilled into the Puerco River through a small stream called Pipeline Arroyo.

About 1.36 tons (1.23 metric tons) of uranium and 46 curies of alpha contaminants traveled 80 miles (129 km) downstream. This pollution reached Navajo County, Arizona, and flowed onto the Navajo Nation. Besides being radioactive and acidic, the spill contained harmful metals and sulfates.

The spill polluted the groundwater and made the Puerco River unsafe. Local residents, mostly Navajo people, used the river for drinking, watering crops, and their animals. They were not warned about the dangers of the spill for several days.

The Governor of New Mexico, Bruce King, did not agree to the Navajo Nation's request for the area to be declared a federal disaster. This limited the help available to the affected people. The nuclear spill received less news coverage than Three Mile Island. This was likely because it happened in a very rural area. Also, it affected a Native American community that was not used to speaking out publicly at that time.

In 2003, the Churchrock Chapter of the Navajo Nation started a project to check the environment. They wanted to see the effects of old uranium mines. They found a lot of radiation in the area, both natural and from mining. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) still lists the Church Rock tailings site as a high-priority cleanup site. This is because contaminated groundwater is still spreading.

Contents

What Caused the Dam to Break?

Around 5:30 AM on July 16, 1979, a crack in the dam at the Church Rock uranium mill opened wider. It became a 20-foot (6.1 m) wide break in the south side of the pond. This allowed 1,100 tons (1,000 metric tons) of solid radioactive waste and about 93 million gallons (352 million liters) of acidic, radioactive liquid to flow out. It went into Pipeline Arroyo, which leads to the Puerco River.

Warnings about a possible spill had been ignored by the state and by United Nuclear Corporation. Even though the mill was only next to the Navajo Nation land, the spilled waste flowed onto their land as it went down the Puerco River.

The spilled liquid was very acidic, with a pH of 1.2. It also had a lot of alpha radiation. Besides radioactive uranium, thorium, radium, and polonium, it contained other metals. These included cadmium, aluminum, magnesium, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, selenium, sodium, vanadium, zinc, iron, and lead. It also had high amounts of sulfates.

The contaminated water traveled 80 miles (129 km) downstream. It went through Gallup, New Mexico, and reached as far as Navajo County, Arizona. The flood caused sewers to back up and affected underground water sources (aquifers). It left behind dirty, standing pools of water along the river.

As the very acidic spill moved downstream, the natural alkaline soils and clays helped to neutralize the acid. They also absorbed many of the harmful substances. The contaminated dirt was slowly spread out by the river and mixed with clean dirt. In some parts of the river with higher pollution, yellow salt crystals formed on the riverbed. These salts contained metals and radioactive materials. They were washed away during later rainstorms.

About a month after the spill, the Puerco River returned to normal levels of salt, acidity, and radioactivity when the water flow was low. However, contaminants could still be detected after heavy rains. The EPA said there were no long-term effects from the spill. But they noted that pollution levels from uranium mines and natural sources were still "environmentally significant."

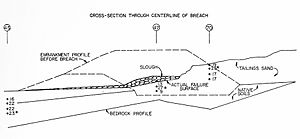

Why the Dam Failed

The dam was the southern wall of one of the mill's three ponds. These ponds were used to evaporate the liquid from the tailings. This left behind solid waste that could be buried. From 1967 to 1982, the mill produced about 4,000 tons (3,629 metric tons) of tailings every day. This was a total of 3.5 million tons (3.17 million metric tons).

The dam was 35 feet (10.7 m) high. It was built on a deep layer of soft, sandy clay, about 100 feet (30.5 m) deep. United Nuclear used a new design suggested by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. This design used earth instead of the tailings themselves as building material. The pond was not lined, which was against the Uranium Mill Tailings Radiation Control Act of 1978. This allowed the liquid waste to leak into the ground. This weakened the dam's foundation and polluted the groundwater.

Cracks formed along the southern part of the dam. These cracks allowed the acidic liquid to get inside and weaken the dam. A sand layer was built to protect the dam from the liquid. However, it was not kept up properly. The liquid in the pond eventually rose 2 feet (0.6 m) higher than the dam was designed for. This was past the point where the sand layer could protect the dam.

The United States Army Corps of Engineers investigated the spill. They reported to Governor Bruce King that the main reason for the failure was the ground settling unevenly under the dam wall. Another report, ordered by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, agreed with this. Also, the way the tailings pond was operated was different from the approved plans. This also helped cause the dam to fail.

United Nuclear's Chief Operating Officer, J. David Hann, blamed the dam's failure on the pointed shape of the bedrock under the dam. He said it acted like a pivot point and weakened the dam.

In December 1977, experts found cracks in the dam wall. Three months later, United Nuclear sealed the cracks. But they did little else, even though the experts urged regular inspections. More cracks were seen in October 1978. Neither the company nor the state engineer were officially told about these cracks. However, a representative from Arizona, Morris K. Udall, told Congress that at least three government agencies had "ample opportunity" to predict the dam would likely fail. At the same hearing, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers stated that if the dam had been built correctly, it would not have failed.

What Were the Effects?

Soon after the dam broke, the radioactivity levels in the river water below the dam were 7,000 times higher than what is allowed for drinking water. United Nuclear first claimed only one curie of radioactivity was released. But this number was later changed to 46 curies by the New Mexico Environmental Improvement Division.

Before the spill, local people used the river for fun and to gather plants. Children often played in the Puerco River. After the spill, residents who waded in the river went to the hospital. They complained of burning feet. Doctors wrongly said they had heat stroke. Some people who touched the contaminated water got burns that led to serious infections and needed amputations.

Many sheep and cattle died after drinking the polluted water. Children also played in pools of contaminated water. The spill polluted shallow underground water sources (aquifers) near the river. Residents used these for drinking and for their animals. About 1,700 people lost access to clean water after the spill.

United Nuclear Corporation gave out 600 gallon (2,271 liter) jugs of clean water. But the affected area needed more than 30,000 gallons (113,562 liters) of water daily. The three community wells serving Church Rock were already closed. One was closed due to high radium levels, and the other two for high levels of iron and bacteria. The Indian Health Service told the tribe to fix five shallow wells along the Puerco River. They said these wells were "not expected to show any contamination, if at all, for several years."

The Navajo Nation spent $100,000 on clean water. In 1981, the New Mexico and federal governments stopped providing water. They had been delivering it by truck since the spill.

A health study in 1989 looked at the effects on people. It said that "the health risk to the public from eating exposed cattle is minimal." This was true unless people ate large amounts of certain parts, like liver and kidney. Another study found much higher levels of radioactive materials in Church Rock cattle compared to animals from non-mining areas. The authors of this study said that contamination would not be a risk if residents did not rely on these animals for food for long periods. However, local Navajo people did rely on them.

A few Navajo children were sent to Los Alamos to be checked for radiation exposure. But no long-term health checks were done. This led a local writer to say that the Indian Health Service spent more effort studying animals than the people affected. No ongoing health studies have been done at Church Rock. Studies since the 1950s have shown that the Navajo people have had higher rates of some cancers than the national average. This is linked to pollution from uranium mines and workers being exposed to radiation.

Cleanup Efforts

United Nuclear first sent small teams with shovels and 55-gallon (208 liter) drums to start cleaning up. But they increased the number of workers after complaints from local residents and pressure from the state. The teams removed 3 inches (7.6 cm) of dirt from the riverbed. They collected about 3,500 barrels (556,000 liters) of waste over three months. However, this was estimated to be only 1% of the solid waste that spilled.

The groundwater remained polluted by the spilled liquid. Rain also carried leftover pollutants downstream into Arizona. New Mexico ordered United Nuclear to monitor pools left by the spill along the Puerco River. But United Nuclear only measured uranium levels. They ignored the presence of thorium-230 and radium-226. These pools contained high levels of sulfuric acid and stayed for more than a month after the spill. This was despite cleanup efforts by the New Mexico Environmental Improvement Division. The NMEID ordered United Nuclear to control leaks from the mill in 1979. The company started a limited leak collection program in 1981.

The Navajo Nation asked the governor to request that the president declare the site a federal disaster area. But he refused. This reduced the help available to local residents. United Nuclear continued to operate the uranium mill until 1982. It then closed because the market for uranium was declining.

United Nuclear used ammonia and lime to make the tailings less acidic from 1979 to 1982. In 1983, the site was added to the National Priorities List by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). This meant it was a Superfund site for investigation and cleanup. This was because radioactive materials and chemicals were found to be polluting local groundwater.

The EPA studied the site from 1984 to 1987. In 1988, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission approved United Nuclear's plan to close and clean up the site.

In 1994, the EPA expanded its efforts. They started a study of all known uranium mines on the Navajo Nation. In 2007, the EPA and United Nuclear removed 175,500 cubic feet (4,970 cubic meters) of radium-polluted soil. This soil was around five buildings, some of which were homes. The soil was moved to a special disposal site away from the area.

In 2003, the Churchrock Chapter of the Navajo Nation started the Church Rock Uranium Monitoring Project. This project aimed to check the environmental effects of old uranium mines. It also helped the community do its own research. Their report in May 2007 found radiation levels many times higher than normal in the area. This radiation came from both natural sources and mining.

In 2008, the U.S. Congress approved a five-year plan. This plan was for cleaning up polluted uranium sites on the Navajo reservation.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Derrame del molino de uranio de Church Rock para niños

In Spanish: Derrame del molino de uranio de Church Rock para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |