Cod Wars facts for kids

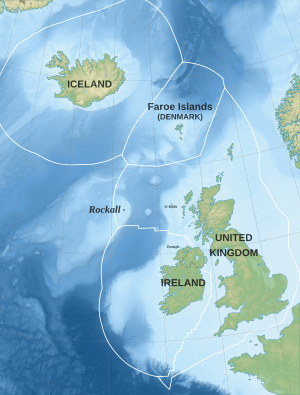

The Cod Wars (also known as the Coastal Wars) were a series of disagreements in the 20th century. They happened between the United Kingdom (with help from West Germany) and Iceland. The main reason for these fights was about fishing rights in the North Atlantic Ocean. Each time, Iceland ended up getting what it wanted.

For a long time, British fishing boats have sailed to waters near Iceland. This started way back in the 14th century. Agreements made in the 15th century led to many arguments between the two countries over hundreds of years. As more people wanted seafood in the 19th century, the competition for fish grew much stronger.

The modern "Cod Wars" began in 1952. Iceland decided to make its fishing waters bigger, from 3 to 4 nautical miles (about 7.4 km). This was based on a decision from the International Court of Justice. The United Kingdom reacted by stopping Icelandic ships from bringing their fish into British ports.

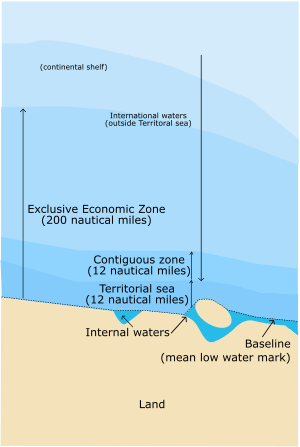

In 1958, after a United Nations meeting where many countries wanted to extend their water limits to 12 nautical miles (about 22 km), Iceland went ahead and did it on its own. They banned foreign fishing fleets from these waters. Britain did not agree with this. This led to three main conflicts over 20 years: 1958–1961, 1972–1973, and 1975–1976.

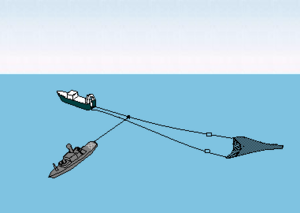

During these conflicts, there was a risk of danger. British fishing boats were protected by the Royal Navy. The Icelandic Coast Guard tried to chase them away. They even used long ropes called hawsers to cut the fishing nets from British boats. Ships from both sides were damaged from ramming each other.

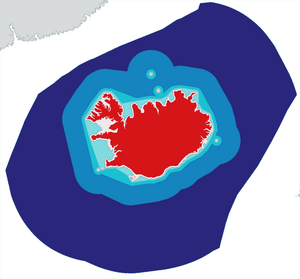

Each time, Iceland won the argument. Iceland even threatened to leave NATO, a military alliance. If Iceland left, NATO would lose an important area for tracking submarines during the Cold War. In 1976, with NATO's help, an agreement was made. The United Kingdom accepted Iceland's 12-nautical-mile zone where only Icelandic ships could fish. They also agreed to a 200-nautical-mile (370 km) Icelandic fishing zone. In this larger zone, other countries needed Iceland's permission to fish. This agreement ended over 500 years of British fishing without limits in these waters.

Because of this, British fishing towns lost access to rich fishing areas. Many jobs were lost, and these communities faced tough times. The UK then changed its own policy. It declared a similar 200-nautical-mile zone around its own waters. Since 1982, a 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone has become the international rule for countries, under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

A British journalist first used the name "Cod War" in 1958. These events were not like typical wars. They were more like serious arguments between countries where military force was sometimes used. Only one person died during the Cod Wars. An Icelandic engineer was accidentally killed in 1973 while fixing his patrol boat after it crashed with a British ship. Another fisherman was seriously hurt in 1976 when his net was cut.

People have different ideas about why the Cod Wars happened. Recent studies look at the money, laws, and strategies that drove Iceland and the UK. They also look at how things inside each country and around the world made the disputes worse. The lessons learned from the Cod Wars are still used to understand how countries interact today.

Contents

Why the Cod Wars Happened

Seafood has been a very important food for people in Britain, Iceland, and other Nordic countries for centuries. These countries are surrounded by some of the best fishing areas in the world. In the 9th century, Viking raiders brought North Sea cod to Britain. Other fish like halibut and hake also became popular.

Fishing Before 1949

By the late 1300s, English fishing boats were sailing to Icelandic waters. They caught so much fish that it caused problems between England and Denmark, which ruled Iceland then. The Danish King Eric even banned all trade between Iceland and England in 1414. He complained to the English King Henry V about too much fishing near Iceland.

English laws to limit British fishing were often ignored. This led to fighting, like the Anglo-Hanseatic War (1469–1474). Diplomats tried to solve these problems with agreements. These allowed British ships to fish in Icelandic waters with special permits for seven years. But this part was removed from a later treaty. This started a long series of arguments between the two countries. From the early 1500s, English sailors and fishermen were very common in the waters off Iceland.

In the late 1800s, steam power allowed fishing boats to travel further. Boat owners wanted to find new fishing grounds. Their large catches near Iceland made them visit more often. In 1893, the Danish government, which still controlled Iceland, claimed a fishing limit of 50 nautical miles (93 km) around its shores. British trawler owners disagreed and kept sending their ships there. The British government did not accept Denmark's claim. They worried it would lead to similar claims by other countries, which would hurt the British fishing industry.

In 1896, the UK and Denmark made an agreement. British ships could use Icelandic ports for shelter if they put away their fishing gear. In return, British ships would not fish in Faxa Bay in a certain area.

Many British trawlers were caught and fined by Danish gunboats for fishing inside the 13-nautical-mile (24 km) limit. The British government did not recognize this limit. The British newspapers started asking why the Royal Navy was not helping. Britain showed its naval power in 1896 and 1897.

In 1899, a British trawler called Caspian was fishing near the Faroe Islands. A Danish gunboat tried to arrest it. The trawler refused to stop and was shot at. The Caspian was eventually caught. But the skipper, Charles Henry Johnson, told his mate to escape after he went onto the Danish ship. The Caspian sped away. The gunboat fired at the unarmed boat but could not catch it. The Caspian returned, damaged, to Grimsby, England. The skipper was jailed for 30 days.

The 'Anglo-Danish Territorial Waters Agreement' of 1901 set a 3-nautical-mile (5.6 km) limit for territorial waters around each country's coastlines. This applied to Iceland, which was part of Denmark at the time. This agreement lasted for 50 years.

Icelandic fishing grounds became very important for the British fishing industry around the end of the 19th century. The First World War reduced fishing activity, which stopped the dispute for a while.

After the war, British catches in Icelandic waters grew a lot. Icelanders became more and more unhappy about the British presence.

From 1949 to 1958

In 1949, Iceland started the process to end the 1901 agreement with the UK. In 1952, Iceland extended its fishing limits from 3 to 4 nautical miles (7.4 km). The UK and Iceland tried to find a solution but could not agree.

From 1952 to 1956, Iceland and the UK argued over Iceland's new 4-nautical-mile fishing limit. Unlike the later Cod Wars, the Royal Navy did not enter Icelandic waters. However, the British fishing industry punished Iceland by banning Icelandic fish from British ports. This ban hurt Iceland's fishing industry a lot, as the UK was its biggest customer.

The Cold War helped Iceland. The Soviet Union, wanting more influence in Iceland, started buying Icelandic fish. The United States, worried about Soviet influence, also bought fish and convinced Spain and Italy to do the same. This made the British ban less effective. Some experts call this period (1952-1956) one of the Cod Wars because it had similar goals and risks.

Just like the other Cod Wars, this dispute ended with Iceland getting what it wanted. The UK recognized Iceland's 4-nautical-mile fishing limits in 1956.

Two years later, in 1958, the United Nations held a conference about the Law of the Sea. Many countries wanted to extend their territorial waters to 12 nautical miles (22 km), but no agreement was reached.

First Cod War (1958–1961)

Quick facts for kids First Cod War |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cod Wars | |||||||||

Coventry City and ICGV Albert off the Westfjords |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Countries involved | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| None | |||||||||

The First Cod War lasted from September 1, 1958, to March 11, 1961. It started when a new Icelandic law took effect. This law made Iceland's fishing zone bigger, from 4 to 12 nautical miles (22 km).

All members of NATO were against Iceland's decision to expand its waters alone. The British said their trawlers would fish with protection from their warships in three areas. In total, twenty British trawlers, four warships, and a supply ship were inside the new zones. This operation was very expensive. In February 1960, Lord Carrington, who was in charge of the Royal Navy, said the ships near Iceland had used half a million pounds worth of oil. Iceland only had seven patrol vessels and one flying boat.

The Royal Navy's presence in the disputed waters caused protests in Iceland. People demonstrated outside the British embassy. The British ambassador even played bagpipe music and military marches to annoy them. Many incidents followed. Iceland had trouble patrolling the large area with its few ships. Only the main ship, Þór, could effectively arrest and tow a trawler to harbor.

On September 4, the Icelandic patrol vessel ICGV Ægir tried to take a British trawler. But HMS Russell stepped in, and the two ships crashed. On October 6, V/s María Júlía fired three shots at the trawler Kingston Emerald, making it flee. On November 12, V/s Þór found the trawler Hackness, which had not stored its nets properly. Hackness did not stop until Þór fired warning shots. Again, HMS Russell came to help. Its captain told the Icelandic captain to leave the trawler alone, as it was not within the 4-nautical-mile limit Britain recognized. The Icelandic captain refused and prepared his gun. The Russell then threatened to sink the Icelandic boat. More British ships arrived, and Þór left.

Icelandic officials threatened to leave NATO and remove US forces from Iceland if the dispute wasn't solved. Because of this, NATO helped to find a solution.

After a UN conference in 1960-1961, the UK and Iceland reached an agreement in February 1961. It said that Iceland would have 12-nautical-mile fishing limits. But Britain would have fishing rights in certain areas for three years. The Icelandic parliament approved the agreement on March 11, 1961.

This deal was very similar to what Iceland had offered in 1958. As part of the agreement, any future disagreements about fishing zones would be sent to the International Court of Justice.

Second Cod War (1972–1973)

| Second Cod War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cod Wars | |||||||||

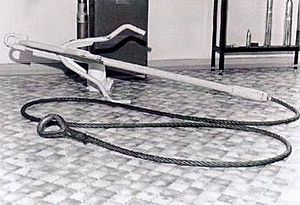

A net cutter, first used in the Second Cod War |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Countries involved | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 1 engineer killed | 1 German trawlerman wounded | ||||||||

The Second Cod War between the United Kingdom and Iceland lasted from September 1972 until November 1973.

The Icelandic government again made its fishing limits bigger, this time to 50 nautical miles (93 km). They had two reasons: to protect fish stocks and to catch more fish themselves. They chose 50 nautical miles instead of 200 because the best fishing grounds were within 50 miles, and it would be easier to patrol.

The British disagreed with Iceland's expansion for two reasons. They wanted to catch as much fish as possible. They also wanted to stop other countries from expanding their fishing zones on their own.

Most Western European countries and the Warsaw Pact (a group of communist countries) were against Iceland's decision. But African countries supported Iceland. They saw Iceland's fight as part of a bigger struggle against colonialism.

On September 1, 1972, the new law expanding Iceland's fishing limits to 50 nautical miles began. Many British and West German trawlers continued fishing inside the new zone. The Icelandic government ignored the treaty that said they should go to the International Court of Justice. They said they were not bound by agreements made by the previous government. The fisheries minister said, "the basis for our independence is economic independence." The next day, the new patrol ship ICGV Ægir chased 16 trawlers out of the 50-nautical-mile zone. The Icelandic Coast Guard started using net cutters to cut the fishing lines of foreign ships.

On September 5, 1972, ICGV Ægir found an unknown trawler. The trawler's captain refused to say its name. After being warned, he played Rule, Britannia! over the radio. Ægir then used its net cutter for the first time, cutting one of the trawling wires. The angry fishermen on the trawler threw coal and a fire axe at the Coast Guard ship. The trawler was identified as Peter Scott.

On November 25, 1972, a crewman on a German trawler was hurt when an Icelandic ship cut his trawling wire. On January 18, 1973, the nets of 18 trawlers were cut. This forced British fishermen to leave the Icelandic zone unless they had protection from the Royal Navy. The next day, large tugboats were sent to defend them. The British decided this was not enough and formed a special group to protect the trawlers.

On January 23, 1973, a volcano erupted in Iceland. This made the Coast Guard focus on rescuing people.

On May 17, 1973, British trawlers left Icelandic waters. But they returned two days later with British warships. This naval operation was called Operation Dewey. Hawker Siddeley Nimrod jets flew over the waters. They told British ships where Icelandic patrol ships were. Icelandic leaders were very angry about the Royal Navy's arrival. They thought about asking the UN Security Council for help. The US ambassador said the Icelandic prime minister even asked the US to bomb the British warships. There were big protests in Reykjavík on May 24, 1973. All the windows of the British embassy were broken.

On May 26, ICGV Ægir told the trawler Everton to stop, but it refused. Ægir chased it, firing warning shots and then live rounds to disable the trawler. Everton was hit four times and started taking on water. But it managed to reach a safe zone, where a British warship helped it. The Icelandic prime minister said this was a "natural and inevitable law-enforcement action."

The Icelandic ship V/s Árvakur crashed into four British vessels on June 1. Six days later, on June 7, ICGV Ægir crashed into HMS Scylla. The Icelandic Coast Guard said Scylla had been "harassing" their boat. The British Ministry of Defense claimed the Icelandic ship intentionally rammed the British warship.

On August 29, the Icelandic Coast Guard had the only confirmed death of the conflict. An engineer on ICGV Ægir died from electric shock after seawater flooded his compartment during repairs. This happened after Ægir crashed with HMS Apollo.

On September 16, 1973, the Secretary-General of NATO came to Reykjavík. He talked with Icelandic ministers, who were being pressured to leave NATO. Both Britain and Iceland were NATO members. The Royal Navy used bases in Iceland during the Cold War to guard the Greenland-Iceland-UK gap, which was important for NATO.

After talks within NATO, British warships were called back on October 3. An agreement was signed on November 8. It limited British fishing in certain areas inside the 50-nautical-mile limit. The agreement was approved by the Icelandic parliament on November 13, 1973. It said British trawlers would catch no more than 130,000 tons of fish per year. This agreement ended in November 1975, and the Third Cod War began.

The Second Cod War almost made Iceland leave NATO and remove US military forces. This was the closest Iceland came to ending its defense agreement with the US. Iceland's NATO membership and the US military presence were very important for Cold War strategy because of Iceland's location.

After the Royal Navy entered the waters, usually four warships and several tugboats protected the British fishing fleet. In total, 32 British warships entered the disputed waters during this Cod War.

C. S. Forester Incident=

On July 19, 1974, a large British fishing trawler, C. S. Forester, was shelled and captured by the Icelandic gunboat V/s Þór. This happened more than nine months after the agreement was signed. The trawler had been fishing inside the 12-nautical-mile limit. Þór chased it for 100 nautical miles (185 km). C. S. Forester was hit by two shells, damaging its engine room and water tank. It was then boarded and towed to Iceland. The skipper was fined and jailed for 30 days, but released on bail. The owners paid a large sum of money to get the ship released. The trawler was allowed to leave with its 200 tons of fish.

Third Cod War (1975–1976)

| Third Cod War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cod Wars | |||||||||

Icelandic patrol ship ICGV Óðinn and British frigate HMS Scylla clash in the North Atlantic. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Countries involved | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

In 1973, at a United Nations conference, several countries supported a 100-nautical-mile (185 km) limit for territorial waters. On July 15, 1975, the Icelandic government announced it would extend its fishing limits again. The Third Cod War (November 1975 – June 1976) began after Iceland expanded its fishing limits to 200 nautical miles (370 km) from its coast. The British government did not accept this large increase. This caused problems with British fishermen working in the disputed zone. This conflict was the toughest of the Cod Wars. The Icelandic Coast Guard cut nets from British fishing trawlers. There were also many incidents of Icelandic ships ramming British trawlers, warships, and tugboats.

One serious event happened on December 11, 1975. Iceland reported that its ship V/s Þór was leaving port when it was told to check on unknown foreign ships. These were three British ships: Lloydsman, a large tugboat; Star Aquarius, an oil rig supply vessel; and Star Polaris. They were hiding from a strong storm inside Iceland's 12-nautical-mile territorial waters. Iceland said that when Þór told them to leave, the tugboats first obeyed. But then Star Aquarius crashed into Þór's side. Lloydsman also hit Þór. Þór was badly damaged. It fired a blank shot, but Star Aquarius hit Þór a second time. Þór then fired a live shot, hitting the front of Star Aquarius. The tugboats then left. V/s Þór, almost sinking, went for repairs.

British reports of this incident are different. They say Þór tried to board one of the tugboats. When Þór pulled away, Lloydsman moved forward to protect Star Aquarius. The captain of Star Aquarius said Þór hit his ship and then fired a shot. Iceland's Ambassador in London said Þór fired in self-defense after being rammed. Iceland asked the UN Security Council for help, but they did not get involved.

The Royal Navy quickly sent many warships to Icelandic waters. The Royal Navy wanted to show what its older warships could do. They were also worried about budget cuts. The Cod Wars were seen as important conflicts for the Royal Navy, similar to the Falklands War later on.

Another incident happened in January 1976. HMS Andromeda crashed into Þór, making a hole in its side. Andromeda's hull was also dented. The British Ministry of Defence said it was a "deliberate attack" on their warship. The Icelandic Coast Guard said Andromeda had rammed Þór by changing course quickly. After this, the Royal Navy was told to be more careful when dealing with Icelandic ships cutting nets.

On February 19, 1976, a British fisherman was seriously hurt when a rope hit him after Icelandic ships cut his net. This was the first British injury of the Third Cod War.

Britain sent a total of 22 warships and reactivated two more from reserve. These were refitted to ram other ships. In addition to warships, Britain also sent seven supply ships, nine tugboats, and three support ships. The Royal Navy was ready to accept serious damage to its warships. Some ships were badly damaged and needed expensive repairs. For example, HMS Yarmouth had its front torn off. Iceland used four patrol vessels and two armed trawlers. The Icelandic government tried to buy US gunboats and then Soviet warships, but was denied.

Things became more serious when Iceland threatened to close the NATO base at Keflavík. This would have greatly hurt NATO's ability to stop the Soviet Union from accessing the Atlantic Ocean. Because of this, the British government agreed that its fishermen would stay outside Iceland's 200-nautical-mile (370 km) zone without a special agreement.

On May 6, 1976, V/s Týr was trying to cut the nets of the trawler Carlisle. Captain Gerald Plumer of HMS Falmouth ordered his ship to ram Týr. Falmouth, moving very fast, rammed Týr, almost flipping it over. Týr did not sink and managed to cut Carlisle's nets. Falmouth rammed it again. Týr was heavily damaged. Its captain ordered his crew to prepare their guns to stop further ramming. Falmouth also suffered heavy damage. There were 55 ramming incidents in the Third Cod War.

With NATO's help, an agreement was reached between Iceland and the UK on June 1, 1976. The British were allowed to keep 24 trawlers within the 200-nautical-mile limit and catch a total of 30,000 tons of fish.

While Iceland came closest to leaving NATO in the Second Cod War, it took its most serious action in the Third Cod War. On February 19, 1976, Iceland ended diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom. Even though the Icelandic government supported Western countries, it linked its NATO membership to the fishing dispute. Iceland hinted it would leave NATO if a good solution wasn't found.

What Happened After

Iceland achieved its main goals. As a result, British fisheries, which were already struggling, were hit hard. They were no longer allowed in their traditional fishing grounds. The economies of large northern British fishing ports like Grimsby and Hull were badly affected. Thousands of skilled fishermen and people in related jobs lost their work. Repairing the damaged Royal Navy warships cost millions of pounds.

In 2012, the British government offered money and an apology to fishermen who lost their jobs in the 1970s. More than 35 years later, the £1,000 compensation offered to 2,500 fishermen was criticized for being too little and too late.

Learning from the Cod Wars

A 2016 study found that Iceland wanted to expand its fishing limits for money and legal reasons. The UK's reasons were about money and strategy. But these reasons alone don't explain why they couldn't agree. Fighting was costly and risky for both sides.

Several things explain why they couldn't agree. Strong national feelings and political competition in Iceland played a role. Pressure from the fishing industry in Britain also made both sides take risks. Also, different government departments and individual diplomats sometimes acted on their own. For example, the British Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries influenced the British government more than the Foreign Office.

A 2017 study says that strong pressures inside each country and mistakes by leaders led to the Cod Wars. The study argues that Iceland won each Cod War because its leaders were too limited by their own country's politics to offer compromises. But British leaders were not as limited by public opinion.

Lessons for International Relations

Experts in international relations have written about the Cod Wars.

The 2016 study says that lessons from the Cod Wars are often used in theories about how countries interact. The Cod Wars are seen as not fitting with the idea that democracy, trade, and international groups make countries peaceful. A 2017 study argues that these "peaceful factors" actually made the disputes more intense. The Cod Wars also show that military power might be less important in international relations than some theories suggest. Experts on unequal negotiations point out that Iceland, even without a lot of power, could still win because it was more committed to its cause.

What Changed After

The 1976 agreement at the end of the Third Cod War forced the UK to stop its "open seas" fishing policy. The British Parliament passed the Fishery Limits Act 1976. This law declared a similar 200-nautical-mile zone around Britain's own shores. This practice later became a worldwide rule under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This convention gave similar rights to every country.

Iceland's victories in the Cod Wars may have made Icelandic nationalism stronger. It also boosted the idea that Iceland can succeed by acting alone or with just one other country, rather than through larger international groups like the European Union.

The Cod Wars are often mentioned in news reports in Iceland and Britain. This happens when there are new fishing disputes or other disagreements between the two countries. For example, they were talked about a lot during the Icesave dispute and before the Iceland–England football match in Euro 2016.

In February 2017, the crews of two ships from the Cod Wars, the British trawler Arctic Corsair and the Icelandic patrol ship Odinn, exchanged bells. This was a friendly gesture between the cities of Hull and Reykjavík. It was part of a project about the history between Iceland and the United Kingdom during and after the Cod Wars.

See also

In Spanish: Guerras del Bacalao para niños

In Spanish: Guerras del Bacalao para niños

- Maritime history of the United Kingdom

- Turbot War

- Lobster War

- Iceland–European Union relations

- 1993 Cherbourg incident

- Scallop War

- List of wars between democracies

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |