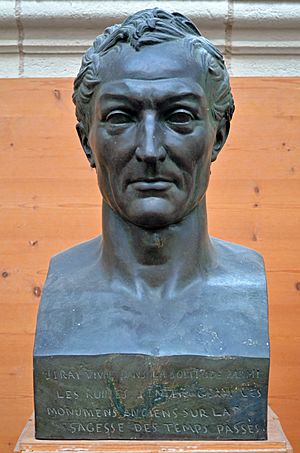

Constantin François de Chassebœuf, comte de Volney facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Constantin François de Chassebœuf, comte de Volney

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 3 February 1757 Craon, Anjou, Kingdom of France

|

| Died | 25 April 1820 (aged 63) |

| Occupation | Philosopher, historian, orientalist and politician |

Constantin François de Chassebœuf, also known as Count de Volney (born February 3, 1757 – died April 25, 1820), was an important French thinker, writer, and politician. He was a philosopher (someone who studies big ideas about life), an abolitionist (someone who wanted to end slavery), and an orientalist (someone who studied the cultures of the East). He first used the name Boisgirais, but later chose Volney. This new name was a mix of Voltaire and Ferney, two places linked to a famous French writer he admired.

Contents

Volney's Life Story

Early Years and the French Revolution

Volney was born in Craon, France, into a family with a good social standing. At first, he was interested in law and medicine. But he soon decided to study classical languages (like Latin and Greek) at the University of Paris. His writings on ancient history, especially about Herodotus, caught the attention of important academic groups. He also became friends with famous thinkers like Benjamin Franklin.

In late 1782, Volney began a journey to the East. He spent about seven months in Egypt. After that, he lived for nearly two years in what is now Lebanon and Israel/Palestine. He did this to learn Arabic, which is spoken in that region. When he returned to France in 1785, he spent two years writing about his travels. His book, Voyage en Egypte et en Syrie (Journey to Egypt and Syria), was published in 1787.

Volney played a part in the French Revolution. He was a member of the Estates-General and later the National Constituent Assembly. In 1791, he wrote a famous book called Les Ruines, ou méditations sur les révolutions des empires (The Ruins, or Meditations on the Revolutions of Empires). In this book, he shared his idea that all religions could unite by finding the common truths they share.

Volney tried to use his ideas about politics and economics in Corsica. In 1792, he bought land there and tried to grow crops usually found in colonies. During a difficult time in the Revolution, he was put in prison. However, he managed to avoid being executed. Later, he taught history at the new École Normale in Paris. Volney was a deist, meaning he believed in a God who created the universe but does not interfere with it.

Volney's Views on Ancient Egypt

Volney wrote about the people of ancient Egypt. He believed that the ancient Egyptians were Black. When describing the Sphinx, a famous statue in Egypt, he noted its features and head looked like those of Black people.

He wrote: "What a topic for thought, to see the current lack of knowledge of the Copts (who are mixed descendants of Greeks and Egyptians), coming from the mix of the deep wisdom of the Egyptians and the bright minds of the Greeks. To think that this group of Black people, who are now treated as slaves and looked down upon, are the very ones to whom we owe our arts, our sciences, and even the way we speak!"

His book, Voyage to Egypt and Syria, was so well-received that Empress Catherine II of Russia sent him a gold medal in 1787 to show her appreciation.

Later Life and Influence

In 1795, Volney traveled to the United States. While there, some people in the government, led by John Adams, thought he might be a French spy. They worried he was preparing for France to take back Louisiana. Because of this, he returned to France. His experiences in the U.S. led him to write Tableau du climat et du sol des États-Unis (Picture of the Climate and Soil of the United States) in 1803.

Volney was not a big supporter of Napoleon Bonaparte. However, Napoleon, who was then leading France, made Volney a count and a member of the Senate. After Napoleon's rule ended, Volney became a Peer of France. This was because he had shown he was against Napoleon's empire. Volney became a member of the Académie française (a famous French academy) in 1795. In his later years, he helped start the study of Eastern cultures in France. He even learned Sanskrit, an ancient Indian language, from a British expert named Alexander Hamilton.

Volney passed away in Paris and was buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Thomas Jefferson and Volney's Ruins of Empires

English versions of Volney's Ruins started to appear soon after it was first published in French. While Volney was in the United States, he and Thomas Jefferson made a secret plan. Jefferson agreed to create a new English translation of the book. Volney visited Jefferson's home, Monticello, for two weeks in June 1796. They also met at the American Philosophical Society, where Volney became a member in 1797. These meetings gave them many chances to talk about the translation.

Jefferson, who was then the Vice President, liked the book's main idea. The book suggested that countries become strong if their government allows people to follow their own good ideas. Jefferson thought this idea perfectly summed up the principles the U.S. was built on. However, Jefferson wanted his translation to be published only for certain readers. This was because the book had some ideas about religion that could cause arguments. Jefferson was getting ready to run for President in 1800. He worried that his political opponents might call him an atheist if people knew he translated Volney's book, which some thought was against religious beliefs.

Research by Gilbert Chinard shows that Jefferson translated the first 20 chapters of the 1802 Paris edition of Volney's Ruins. These chapters look at human history from the view of a thinker from the Enlightenment period. It seems Jefferson became too busy with the 1800 Presidential campaign and couldn't finish the last four chapters. In these final chapters, Volney describes a "General Assembly of Nations." This is a made-up meeting where each religion tries to prove its version of "the truth." Since no religion can scientifically prove its main claims, Volney ends the book by calling for a clear separation of church and state:

From this we conclude, that, to live in harmony and peace...we must trace a line of distinction between those (assertions) that are capable of verification, and those that are not; (we must) separate by an inviolable barrier the world of fantastical beings from the world of realities...

Since Jefferson could not finish the translation, the last four chapters were translated by Joel Barlow. He was an American writer living in Paris. Barlow's name then became linked to the whole translation, making Jefferson's part in the project less known.

Christ Myth Theory

Volney and Charles-François Dupuis were among the first modern writers to suggest the Christ myth theory. This idea proposes that Jesus may not have been a real historical person. Volney and Dupuis argued that Christianity was a mix of different ancient mythologies. They believed Jesus was a mythical character. However, Volney also thought there might have been a less known historical figure whose life was later combined with stories about the sun. Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin were interested in this theory.

Volney's Writings

- Travels in Syria and Egypt, During the Years 1783, 1784, & 1785 (Volume 1, Volume 2, 1788)

- The Ruins: Or a Survey of the Revolutions of Empires (1796)

- New Researches on Ancient History (1819)

- The Ruins; Or, Meditation on the Revolutions of Empires: And The Law of Nature (1890)

Volney's Legacy

Many places and awards have been named after Constantin Volney, honoring his contributions.

- Volney, New York is a town in the United States named after him.

- The Prix Volney is an award founded by Volney himself in 1803. It was originally a gold medal worth 1,200 francs.

- The Volney Hotels in New York, Paris, and Saumur were named in his honor.

- Many streets in France are named Rue Volney, including in Paris, Angers, Mayenne, Brest, Lyon, Saumur, and Clermont-Ferrand.

- Boulevard Volney can be found in Rennes, France, and Laval, France.

- Place Volney is a square in Craon, France.

- An amphitheatre at the University of Angers is named after him.

- Collège Volney is a school in Craon, France.

- Volney Lodge is a Masonic lodge in Laval (Mayenne).

- Cercle Volney was a group for artists and writers in Paris.

See also

In Spanish: Volney para niños

In Spanish: Volney para niños

- Volney prize

- Les Neuf Sœurs

- Society of the Friends of Truth

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |