Czech literature facts for kids

Czech literature is all the amazing stories, poems, and plays written in the Czech language. It also includes works by Czech people or from the Czech Republic (and its older forms like Czechoslovakia).

Even though most Czech literature today is in Czech, in the past, many important works were written in other languages. These included Latin and German.

Contents

Early Czech Writings (Middle Ages)

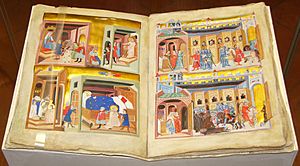

The Czech lands became Christian around the 9th and 10th centuries. The very first writings from this area were in Latin, mostly from the 12th and 13th centuries.

Most of these early works were chronicles (history books) and hagiographies (stories about saints). These stories focused on Czech saints like Ludmila, Wenceslas, Procopius, Cyril, Methodius, and Adalbert.

The most important history book from this time was the Chronica Boemorum (Bohemian Chronicle) by Cosmas. He wrote it to support the ruling family. Other writers later added to Cosmas's work.

Czech Language Grows

In the 13th century, Czech rulers became more powerful and connected with Western Europe. This brought German courtly poetry, called Minnesang, to Bohemia.

However, after a king was killed in 1306, Czech nobles wanted literature in their own language. Even so, German remained important for writing in Bohemia for a long time.

New Czech literature included epic poems, which were long stories about heroes or religious tales. Prose (regular writing, not poetry) also started to develop. This included administrative texts and early Czech-Latin dictionaries. Important history books like the Chronicle of Dalimil were also written in Czech.

The Reformation Period

- Further information: Bohemian Reformation

The Hussite movement in the 15th century changed Czech literature a lot. This period focused on religious ideas, and most writings were in prose. Jan Hus began writing his theological works in the early 15th century. He wrote in both Latin and Czech.

Hus's writings were about religious questions. He also published Czech sermons and created rules for Czech spelling and grammar. These rules later helped create modern Czech.

Writings from the Hussite period often focused on social issues. They were meant for ordinary people, not just nobles. Religious songs in Czech also became popular, replacing Latin hymns. An example is the Jistebnický kancionál (Jistebnice Hymnal).

Humanism and Printing

After the Hussite wars, a new cultural movement called Humanism arrived. Humanists admired ancient Greek and Roman writings. During this time, Catholic writers often wrote in Latin, while Protestant writers used Czech.

New writing styles helped scholars like Veleslavín make Czech grammar more complex. Many new words also entered the language. The invention of Gutenberg's printing press made books much easier to get. This slowly changed how important literature was in society.

The Baroque Period

After the Battle of the White Mountain, Czech Protestants faced hard times. Many were forced to leave Bohemia, and the language became less important. This split Czech literature into two parts: Catholic works written in Bohemia and Protestant works written by Czechs living in other countries.

Because nobles in Bohemia were not big readers of Czech literature, it didn't grow as much as in other European countries during this time.

The most famous Czech Protestant writer of this period was John Comenius. He was a teacher, religious thinker, and philosopher. He wrote books on grammar, education, and religion. After he died in the late 17th century, Protestant literature in Czech almost disappeared.

Catholic Baroque works included religious poetry and prose, like stories about saints and historical accounts.

The Enlightenment Era

At the end of the 18th century, big changes happened in the Czech lands. Emperor Josef II ended the old feudal system and allowed more religious freedom. New ideas from the Enlightenment encouraged using reason and science in all parts of life.

People started to believe that a nation needed its own culture and literature in its own language. In literature, this meant new interest in novels, Czech history, and the development of Czech culture.

Josef Dobrovský was very important. He rewrote the rules for Czech grammar. Writers like Václav Matěj Kramerius wrote novels, and Antonín Jaroslav Puchmayer worked on developing Czech poetry.

Literature began to be read by more people, not just priests. It became a way for artists to express themselves. At first, new Czech literature copied popular German styles, but it later became more unique. This was especially true for drama.

The 19th Century

The early 19th century saw a shift from Enlightenment ideas to romanticism. Writers still used old poetic forms but also focused more on feelings and folk-inspired works. This was when the idea of a truly national Czech literature and culture grew stronger.

Josef Jungmann was a key figure. He translated many world classics into Czech and worked hard to make Czech literature respected. František Palacký and Pavel Jozef Šafárik explored Czech history. To prove how old and rich Czech literature was, some historians even tried to find ancient heroic poems. They found the Dvůr Králové Manuscript and Zelená Hora Manuscript, but these were later found to be fakes.

New Literary Styles

By the 1830s, Czech literature had a strong foundation. Authors then focused more on making their works artistic. Two main types of literature appeared:

- Biedermeier literature: This aimed to teach readers and encourage loyalty to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Writers included Karel Jaromír Erben and Božena Němcová.

- Romanticism: This style focused on individual freedom, feelings, and the subconscious. Karel Hynek Mácha was a famous romantic poet.

These authors often published their works in newspapers or in the literary magazine Květy (Blossoms).

After 1848, a new group of Czech authors emerged. They published their work in the almanac Máj (May). These writers wanted Czech literature to be part of European culture. They also wrote about the effects of industrialization and focused on simple life.

Later in the century, writers moved towards realism and naturalism. They focused on everyday life and ordinary people, often showing characters' speech. They explored two main topics:

- Life in Czech villages, seeing them as places of good morals.

- Life in Prague, especially among the working classes.

The very end of the 19th century brought modernism. Authors in this period often had critical views of older generations. They also saw the literary critic as an important helper for artists. Famous poets included Josef Svatopluk Machar and Otokar Březina.

The 20th Century

The start of the 20th century was a big turning point. Czech literature finally became art for art's sake, not just to educate or serve the nation. Writers looked to France, Northern Europe, and Russia for inspiration.

New poets focused on real life, without too much emotion or complex symbols. Many of them were interested in anarchism and the women's movement. In prose, new styles like impressionism and naturalism became popular.

Before World War I, some Catholic authors returned to writing. The avant-garde movement also entered Czech literature, trying to show the fast changes in society. Early avant-garde styles included cubism and futurism.

World War I and Between the Wars

World War I brought difficulties for Czech culture. Writers often looked back to traditional Czech values and history. The war also caused a crisis of faith in progress, leading to styles like expressionism.

The time between the two World Wars (the First Republic) was a golden age for Czech literature. The new country allowed many different ideas, leading to a boom in writing. A major theme was the war itself – its cruelty, but also the heroic actions of the Czech Legion. The Good Soldier Švejk by Jaroslav Hašek is a famous anti-war comedy novel, translated into many languages.

A new group of poets brought back the avant-garde, with styles like "poetry of the heart." A unique Czech literary style, poetism, was developed by the group Devětsil. They believed poetry should be part of everyday life.

Prose writing became more complex, using multiple viewpoints. Utopian and fantastic literature became popular, as did documentary prose (trying to show the world accurately). Karel Čapek wrote many important works during this time. Drama also followed these new styles, with experimental theater groups.

The 1930s and World War II

The 1930s brought economic and political problems. Writers focused on public issues and spirituality. Poetry became darker, with themes of death and fear. Older avant-garde writers turned to surrealism.

Prose moved towards long, epic stories and psychological novels. Karel Čapek wrote his most political plays in response to the rise of dictators. After the Munich Agreement in 1938, literature called for national unity.

World War II and the German protectorate deeply affected Czech literature. Many authors did not survive or had to leave the country. Free newspapers and publishers were shut down. This led to a split in literature that lasted until 1989:

- Domestic published: Works allowed by the government.

- Domestic illegal: Works written in secret, not published openly.

- Exile literature: Works by authors living outside Czechoslovakia.

During the war, literature focused more on tradition and history. Poetry became quieter, emphasizing language as a part of national identity. Historical novels became popular as a way to write about the present in a hidden way.

Post-War and Communism

After World War II, Czech literature remained split. Under the communist government, literature became a place for freedom and democracy. Writers were admired not just for their art, but for standing up to the government.

In 1948, the Communists took full control. Any literature that disagreed with the government was banned, and authors were punished. The official style became socialist realism, which meant art had to serve the state. Many authors went into exile. Those who stayed often wrote in secret. Their works were only published much later.

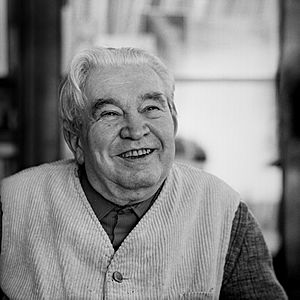

Censorship slowly eased in the late 1950s. Some poets were allowed to publish again. In the 1960s, reforms in the Communist party led to more literary freedom. Authors like Milan Kundera and Ivan Klíma wrote about personal and moral issues. Bohumil Hrabal became a very important prose writer, known for his unique style and everyday language.

The 1960s also saw new authors who grew up under Stalinism. Their works focused on living in the world as it was, with themes of honesty and responsibility. Playwrights like Václav Havel became famous. This era of freedom ended suddenly with the Soviet invasion in 1968, leading to "normalization."

Normalization and After

Normalization brought back strict censorship. Many literary magazines closed, and authors who didn't follow the rules were silenced. The split into legal, illegal, and exile literature became even stronger. Many authors fled to other countries, but their works were often only known through translations.

Underground presses, called samizdat, secretly published works by banned authors. Ludvík Vaculík and Václav Havel organized some of the largest samizdat editions. Many of these illegal authors signed Charta 77, a human rights document, and were jailed for it. Samizdat literature often returned to Catholic themes, memoirs, and honest accounts of daily life.

The new generation of writers in the 1980s often rebelled against society. Their works were sometimes harsh and aggressive. Postmodernism also influenced literature.

The fall of communism in 1989 brought freedom back to Czech literature. Works by many previously banned or exiled authors were finally published. Many of them returned to public life. Today, writers like Petr Šabach, Jáchym Topol, Miloš Urban, Petra Hůlová, and Michal Viewegh are well-known and sell many books. Czech poetry also has strong voices like Petr Borkovec.

Contemporary Czech Authors

- Michal Ajvaz

- Jan Balabán

- Josef Formánek

- Ivan Martin Jirous

- Jiří Hájíček

- Emil Hakl

- Petra Hůlová

- Milan Kundera

- Patrik Ouředník

- Sylvie Richterová

- Jaroslav Rudiš

- Pavel Řezníček

- Petr Stančík

- Michal Šanda

- Jáchym Topol

- Miloš Urban

- Jaroslav Velinský

- Michal Viewegh

- Radka Denemarková

- Jaroslav Čejka (born 1943)

Czech Literary Awards

- Jaroslav Seifert Prize

- Jiří Orten Award

- Magnesia Litera Prize

See also

In Spanish: Literatura en checo para niños

In Spanish: Literatura en checo para niños

- Otto's encyclopedia

- Libri Prohibiti

- List of Glagolitic manuscripts

- Czech science fiction and fantasy