Ellen Wilkinson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ellen Wilkinson

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

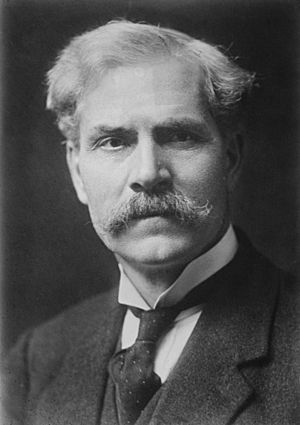

Wilkinson in 1924

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Minister of Education | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 3 August 1945 – 6 February 1947 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Clement Attlee | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Richard Law | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | George Tomlinson | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Labour Party | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 4 January 1944 – 3 August 1945 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader | Clement Attlee | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | George Ridley | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Harold Laski | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 8 October 1891 Manchester, England |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 6 February 1947 (aged 55) London, England |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Labour | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Other political affiliations |

Communist Party of Great Britain (1920–1924) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | University of Manchester (BA) | ||||||||||||||||||||

Ellen Cicely Wilkinson (born October 8, 1891 – died February 6, 1947) was a British politician from the Labour Party. She became the Minister of Education in July 1945 and held this role until her death. Earlier in her career, as a Member of Parliament (MP) for Jarrow, she became famous for leading the 1936 Jarrow March. This was a march of unemployed people from Jarrow to London, asking for the right to work. Even though it didn't immediately solve their problems, the march became a powerful symbol of the 1930s. It helped change how people thought about unemployment and fairness after World War II.

Ellen Wilkinson grew up in a working-class family in Manchester and became interested in socialism when she was young. After studying at the University of Manchester, she worked for women's rights and as a trade union officer. She was inspired by the Russian Revolution of 1917 and joined the British Communist Party. She believed in big changes for society but also worked through the Labour Party to achieve them. In 1924, she was elected as a Labour MP for Middlesbrough East. She supported the General Strike in 1926. After losing her seat in 1931, she became a journalist and writer. She returned to Parliament as Jarrow's MP in 1935. She strongly supported the Republican government during the Spanish Civil War and visited the war zones many times.

During the Second World War, Wilkinson was a junior minister in Churchill's government. She worked mainly at the Ministry of Home Security, helping with air raid shelters and civil defense. When Clement Attlee formed his government after the war, he made Wilkinson the Minister of Education. By this time, she was not very well due to years of hard work. Her main goal was to put the 1944 Education Act into action. This law aimed to raise the school-leaving age from 14 to 15. In the very cold winter of 1946–47, she became ill with a lung disease and died in February 1947.

Contents

Life Story of Ellen Wilkinson

Early Life and Education

Childhood in Manchester

Ellen Wilkinson was born on October 8, 1891, in Chorlton-on-Medlock, Manchester. She was the third of four children. Her father, Richard Wilkinson, worked in cotton and later became an insurance agent. Her mother was Ellen Wood. Richard Wilkinson was a strong believer in his local Methodist church. He believed in hard work and helping yourself. He made sure his children got the best education they could and encouraged them to read a lot.

Ellen started school at age six. She was often sick as a child and stayed home for two years, using that time to learn to read. When she returned, she quickly caught up. At age 11, she won a scholarship to Ardwick Higher Elementary Grade School. She was often outspoken and rebellious. After two years, she moved to Stretford Road Secondary School for Girls. She read many books, encouraged by her father, including works by Darwin.

Teaching was one of the few jobs available for educated working-class girls. In 1906, Ellen won a scholarship that helped her start teacher training. She attended Manchester Day Training College and also taught at Oswald Road Elementary School. She liked to make learning interesting for her students, which sometimes caused problems with her bosses. This made her realize teaching wasn't for her. At college, she learned about socialism through the writings of Robert Blatchford. At 16, she joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP). She met Katherine Glasier, a socialist who greatly influenced her. She also met Hannah Mitchell, a supporter of women's right to vote. Wilkinson then joined the fight for women's suffrage, helping to hand out leaflets and put up posters.

University Days

Ellen wanted a career outside of teaching. In 1910, she won a scholarship to Manchester University. There, she got more involved in politics. She joined the university's Fabian Society, a group that promoted socialist ideas. She continued her work for women's suffrage, impressing Margaret Ashton, the first woman on Manchester City Council. Through her activism, Wilkinson met many important leaders of the left-wing movement. She was also influenced by Walton Newbold, who later became the first Communist MP in the UK. They were briefly engaged and remained political friends.

In her last year at university, Wilkinson joined the University Socialist Federation. This group connected socialist students from across the country. She met new people and attended summer schools where she heard lectures from Labour leaders. Despite these activities, she studied hard and won several awards. In 1913, she earned her BA degree. She said she "deliberately sacrificed" a top grade to help with a strike happening in Manchester.

Starting Her Career

Working for Change

After university in 1913, Wilkinson became a paid worker for the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). She helped organize the Suffrage Pilgrimage in July 1913. Over 50,000 women marched from all over the country to a big rally in Hyde Park, London. She learned a lot about how politics and campaigns worked. She became a skilled speaker, able to speak confidently even in difficult meetings.

When World War I started in August 1914, Wilkinson believed it was a war for empires, not for workers. She became honorary secretary of the Manchester branch of the Women's Emergency Corps. This group found war work for women volunteers. In July 1915, she became a national organizer for the Amalgamated Union of Co-operative Employees (AUCE). Her job was to recruit women into the union. She fought for equal pay for women and for the rights of lower-paid workers. She organized successful strikes in several cities.

Her work for the union led to new friendships, including with John Jagger, who later became the union's president. She remained active in the Fabian Society. She also joined the National Guilds League, which supported workers having more control in industries. Wilkinson also visited Ireland in 1920 and spoke out against the British government's actions there.

Joining the Communist Party

Like many others, Wilkinson's views became more radical after the Russian Revolution of 1917. She saw communism as the future. When the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was formed in 1920, Wilkinson was one of its founding members. For a few years, the CPGB was her main political focus. However, she also kept her membership in the Labour Party, which allowed people to be members of both parties at the time.

In 1921, Wilkinson went to Moscow for a Communist Women's Congress. There, she met Russian communist leaders like Leon Trotsky and Nadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin's wife. Wilkinson admired Krupskaya's speech. The meeting led to the creation of the Profintern, an organization that aimed for revolutionary change through worker action. At home, Wilkinson continued to promote Russia's achievements, especially how it helped women workers. However, she started to disagree with the Communist Party's strategies.

Becoming an MP

Wilkinson was a strong supporter of the National Council of Labour Colleges, which aimed to educate working-class students. She became a candidate for Parliament, supported by her union. In 1923, while still a Communist Party member, she tried to become the Labour Party's candidate for the Gorton area. She wasn't chosen, but in November 1923, she was elected to Manchester City Council. Her main concerns on the council were unemployment, housing, child welfare, and education.

When the Prime Minister called a general election in December 1923, Wilkinson ran as Labour's candidate for Ashton-under-Lyne. She openly spoke about her Communist beliefs. She came third in the election. After this election, the Labour Party formed a government but banned people from being members of both the Communist Party and the Labour Party. Wilkinson chose to leave the Communist Party. She said their methods made it hard to work with other progressive groups. After this, she was chosen as Labour's candidate for Middlesbrough East.

Member of Parliament for Middlesbrough

In Parliament, 1924–1929

On October 8, 1924, the Labour government resigned. In the election that followed, Labour lost many seats. Wilkinson was the only woman elected for Labour. She won Middlesbrough East by a small margin.

When Wilkinson arrived in Parliament, many newspapers wrote about her bright red hair and colorful clothes. She told other MPs that she represented an area with a lot of iron and steel production, even though she didn't "look like it." One newspaper described her as a "strong, determined feminist and a very tough, forceful, and smart politician." A police officer once tried to stop her from entering a room in Parliament because she was a woman. Wilkinson replied, "I am not a lady - I am a Member of Parliament." She helped pass a law that corrected problems affecting widows' pensions. She also worked with a Conservative MP, Lady Astor, to stop cuts to women's training centers. While she often spoke about women's issues, she was primarily a socialist.

During the General Strike in May 1926, Wilkinson traveled around the country to support the striking workers. She was very upset when the Trades Union Congress called off the strike. She helped raise money for the miners who continued to strike. Wilkinson wrote about the strike in A Workers' History of the Great Strike (1927) and in her novel, Clash (1929). She also visited the United States to raise money for the miners.

Wilkinson was always against imperialism, which is when one country controls another. In 1927, she attended a conference in Brussels where she met and became friends with the Indian leader Jawaharlal Nehru. In 1927, she was elected to the Labour Party's National Executive Committee. This gave her a say in how the party made its policies. She was a tireless campaigner for women's equality. On March 29, 1928, Wilkinson voted for the law that gave all women aged 21 or over the right to vote. She said that this was a "great act of justice" for the women of the country.

In Government, 1929–1931

In May 1929, a general election was called. Wilkinson helped write Labour's plans for the election. In Middlesbrough, she was re-elected with more votes. Labour became the largest party, and Ramsay MacDonald formed his second government. Wilkinson was not made a minister, but she became a special assistant to a junior health minister. This showed she was expected to get a bigger role later.

MacDonald's government soon faced big problems: rising unemployment and a worldwide economic downturn. The Labour Party was divided. Some, like Wilkinson, believed the solution was to increase spending power for the poorest people. Wilkinson supported a plan for public works to create jobs, but the government rejected it because of the cost.

With Wilkinson's help, a law about mental health was passed in 1930. She also supported a bill to limit shopworkers' hours to 48 a week. As Parliament continued, it became harder to pass social laws because of the financial crisis and opposition from the House of Lords.

The Labour Party became even more divided in 1931. The government struggled to make big spending cuts. The government collapsed on August 23, 1931. MacDonald and a few Labour MPs formed a new government with the Conservatives and Liberals. Most of the Labour Party, including Wilkinson, went into opposition. In the general election that followed, Labour lost badly. Wilkinson lost her seat in Middlesbrough East.

Out of Parliament, 1931–1935

Wilkinson explained Labour's defeat in a newspaper article. She said the party lost because it was "not socialist enough." She wrote many articles about this idea. She also published Peep at Politicians, a funny book about politicians. Her second novel, The Division Bell Mystery, was published in 1932. It was a mystery set in the House of Commons.

In 1932, Wilkinson visited India to report on conditions there. She met Gandhi, who was in prison, and believed his cooperation was key to peace. When she returned, she wrote a report called The Condition of India (1934). She also visited Germany shortly after Hitler came to power in 1933. She wrote a pamphlet, The Terror in Germany, about the early actions of the Nazi party. She also wrote a book, Why Fascism?, which argued that workers needed to unite to fight fascism in Europe.

Meanwhile, she was chosen as the Labour candidate for Jarrow, a shipbuilding town. Jarrow had been badly affected by the closure of its main shipyard, Palmers. In 1934, Wilkinson led a group of unemployed people from Jarrow to meet the Prime Minister, MacDonald. She received sympathy but no real help. She was not impressed by the government's law to help struggling areas, saying it didn't provide enough money.

Member of Parliament for Jarrow

The Jarrow March

In the November 1935 general election, Wilkinson was elected as Jarrow's MP. Even though Jarrow was very poor, people hoped a new steelworks would bring jobs. However, the steel industry leaders opposed this plan. On June 30, 1936, Wilkinson asked the minister in charge to make the steel industry "less selfish." Her request was ignored.

Wilkinson said the minister's dismissive words "kindled the town." The town council decided to organize a march to London to present a petition to the government. Previous marches of the unemployed were often linked to communist groups. The Jarrow council wanted their march to be free of political labels and supported by everyone in the town. Some church leaders and even some in the Labour Party were hesitant.

On October 5, 1936, 200 chosen marchers set off from Jarrow Town Hall. They walked 282 miles, aiming to reach London by October 30. Wilkinson did not march the whole way, but joined them when she could. At the Labour Party conference, she was criticized for "sending hungry and ill-clad men across the country." On October 31, the marchers reached London, but the Prime Minister refused to meet them. On November 4, Wilkinson presented the town's petition to Parliament. It was signed by 11,000 citizens of Jarrow, asking for work to be provided. The minister said the unemployment situation in Jarrow had improved, which a Labour MP called "an affront to the national conscience."

The marchers returned to Jarrow by train. Their unemployment benefits were reduced because they had been "unavailable for work." Historians say the Jarrow March was important for the future. It "helped to shape how people saw the 1930s" and led to social reforms. It also made the idea of social justice more popular. Wilkinson wrote about Jarrow's struggles in her book, The Town that was Murdered (1939). She wrote that Jarrow's problems were a sign of a bigger national issue.

Global and Local Issues

In November 1934, Wilkinson visited Spain to report on a miners' uprising. She was forced to leave the country. Despite being banned from Germany, she continued to visit secretly. She was the first to report Hitler's plan to march into the Rhineland in March 1936. Spain became very important to her in her fight against fascism. When the Spanish Civil War began, Wilkinson helped set up committees to provide medical aid and relief for Spain. She argued in Parliament that Britain's non-intervention policy was helping General Francisco Franco. She visited Spain again in 1937 and saw the terrible effects of bombing on villages. After seeing starving schoolchildren in Madrid, she started a "Milk for Spain" fund.

Wilkinson had left the Communist Party, but she still had strong links with other communist groups. However, she was careful not to risk losing her seat in Parliament. In 1937, Wilkinson helped start the left-wing magazine Tribune. She wrote about the need to fight unemployment, poverty, and poor housing. She also introduced a bill to regulate hire purchase agreements, which helped protect people buying things on credit. This bill became law in 1938.

Wilkinson strongly opposed the government's policy of trying to avoid conflict with European dictators. In Parliament, on October 6, 1938, she criticized the Prime Minister for signing the Munich Agreement. She said he had given away "practically everything for which this country cared." On August 24, 1939, she attacked the Prime Minister for not allying with Russia against Hitler. She said he put the interests of his class before the national interest.

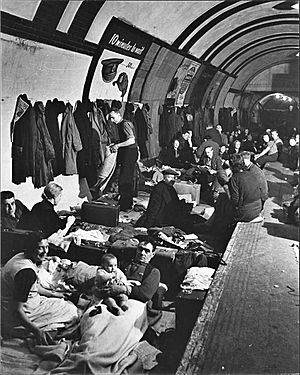

Second World War Role

Wilkinson supported Britain's decision to declare war on Germany in September 1939. In May 1940, when Winston Churchill formed his government, Wilkinson was appointed a junior minister at the Ministry of Pensions. In October 1940, she moved to the Ministry of Home Security. There, she was responsible for air raid shelters and civil defense. When German planes started bombing British cities in 1940, many Londoners used Underground stations as shelters. By the end of 1941, Wilkinson had overseen the distribution of over half a million "Morrison shelters." These were reinforced steel tables that families could sleep under at home. The press called her the "shelter queen." Wilkinson often visited bombed cities to support people and boost morale. She also approved the conscription of women for fire-watching duties, which was controversial.

Working as a minister changed Wilkinson's views. She moved away from some of her earlier left-wing ideas. She supported the decision to ban a communist newspaper during the war because of its anti-British propaganda. She also voted for laws that banned strikes in important industries. She became more accepted within the Labour Party. In June 1943, she became vice-chairman of the party's National Executive. She became chairman in January 1944. In 1945, she was made a Privy Counsellor, a high honor. In April 1945, she went to San Francisco to help set up the United Nations.

After the War

Becoming Education Minister

Wilkinson had a close political relationship with Herbert Morrison. She believed he, not Clement Attlee, should lead the Labour Party. In the general election in July 1945, Labour won a huge victory. Attlee quickly formed a government. He appointed Morrison as deputy prime minister and Wilkinson as Minister of Education, giving her a seat in the cabinet.

Wilkinson was the second woman to join the British cabinet. As Minister of Education, her main goal was to put the 1944 Education Act into action. This law made secondary education free for everyone and raised the school leaving age from 14 to 15, starting in 1947. The Act didn't say how secondary education should be organized. Many experts thought children should take an "11-plus" exam to decide if they went to a grammar (academic), technical, or "modern" school. However, many in the Labour Party wanted "comprehensive" schools, which would be large schools with different courses for all abilities. Wilkinson believed such a big change was not possible at the time. She focused on more achievable reforms. She thought that selection at 11 would allow smart students from all backgrounds to go to grammar schools.

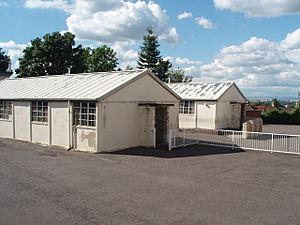

Wilkinson's first priority was raising the school leaving age. This meant hiring and training thousands of new teachers. It also meant creating classroom space for nearly 400,000 more children. Under a special training scheme, former service members could train as teachers quickly. Temporary huts were built to expand school buildings. Wilkinson was determined that the higher leaving age would start on April 1, 1947, as planned. The final approval for this date was given on January 16, 1947.

Other changes during her time as minister included free school milk and better school meals. She also increased university scholarships and expanded part-time adult education. In October 1945, she went to Germany to see how their education system could be rebuilt after the war. She was amazed at how quickly schools and universities were reopening. She also visited Gibraltar, Malta, and Czechoslovakia. In November 1945, she led an international conference in London. This led to the creation of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) a year later. In one of her last speeches, she said UNESCO stood for "standards of value" and would "do great things."

Illness and Passing

Wilkinson suffered from bronchial asthma for most of her life. Her health was made worse by overwork. She had often been ill during the war. On January 25, 1947, she attended an outdoor event in Bristol. The winter was extremely cold. Soon after, Wilkinson developed pneumonia. On February 3, she was found in a coma in her London flat. She died on February 6, 1947, in St Mary's Hospital, Paddington.

Her Impact and Legacy

Wilkinson was known for her short height, red hair, and strong political views. People called her the "Fiery Particle" and "Red Ellen." She wore bright, fashionable clothes and had a forceful personality. An obituary said that "wherever there was a row going on... that rebellious redhead was sure to be seen." Later in her career, she became more practical. She believed that democracy offered a better way to make social progress. However, she never lost her independent thinking. She sought power to help the weak.

A former Conservative MP, Thelma Cazalet-Keir, said that Ellen Wilkinson was never boring. "Whatever she did, wherever she went, she created an atmosphere of excitement and interest."

During her career, Wilkinson helped make changes in many areas. These included equal voting rights for women and equal pay for women in government jobs. She also helped provide air raid shelters and protected the rights of people buying on credit. Historian David Kynaston says her biggest achievement was successfully raising the school leaving age on time. Her successor as education minister said she fought very hard to make sure this reform happened. Wilkinson was sometimes criticized for working on too many causes. However, her book The Town that was Murdered brought attention to the struggles of Jarrow. It showed the impact of unchecked capitalism on working-class communities.

Wilkinson never married. She had many close friendships with men. Her long association with Herbert Morrison began early in her career. Their relationship was likely more than just friendship, but her private papers were destroyed after her death.

On January 25, 1941, Wilkinson received the freedom of the town of Jarrow. In May 1946, she received an honorary doctorate from the University of Manchester. Her name is remembered in several schools, like The Ellen Wilkinson School for Girls in London. The Ellen Wilkinson Building at the University of Manchester also bears her name. Blue plaques mark her birthplace and her time at the university. In 2016, Wilkinson was chosen in a public vote to have the first female statue in Middlesbrough. Her name is also etched on the plinth of the statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square, London.

Books by Ellen Wilkinson

- A Workers' History of the Great Strike (1927) – Co-authored with Frank Horrabin and Raymond Postgate.

- Clash (1929) – A novel.

- Peeps at Politicians (1931)

- The Division Bell Mystery (1932) – A mystery novel.

- The Terror in Germany (1933)

- Why Fascism? (1934) – Co-authored with Edward Conze.

- Why War?: a handbook for those who will take part in the Second World War (1935) – Co-authored with Edward Conze.

- The Town That Was Murdered (1939)

- Plan for Peace: How the People can win the Peace (1945)

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |