Harold Laski facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Harold Laski

|

|

|---|---|

Laski in 1936

|

|

| Born |

Harold Joseph Laski

30 June 1893 Manchester, England

|

| Died | 24 March 1950 (aged 56) London, England

|

| Political party | Labour |

| Spouse(s) |

Frida Kerry

(m. 1911) |

| Alma mater | University College London, New College, Oxford |

|

Notable work

|

A Grammar of Politics (1925) |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | London School of Economics |

| Doctoral students |

|

| Other notable students |

|

| Influences |

|

| Influenced | |

Harold Joseph Laski (born June 30, 1893 – died March 24, 1950) was an English thinker and writer. He focused on political science and economics. Laski was very involved in politics. He led the British Labour Party from 1945 to 1946. He was also a professor at the London School of Economics from 1926 until his death.

At first, Laski believed in pluralism. This idea means that local groups like trade unions are very important. Later, he started to think that a workers' revolution might be needed. He even suggested it could be violent. This idea made other Labour leaders angry because they wanted peaceful change.

Laski was a major supporter of Marxism in Britain between the two World Wars. His teaching inspired many students. Some of them later became leaders in newly independent countries in Asia and Africa. He was a leading thinker for the Labour Party's left wing. They trusted and hoped in Joseph Stalin's Soviet Union. However, moderate Labour politicians, like Prime Minister Clement Attlee, did not trust him. He never got a big government job.

Laski was born into a Jewish family. He also supported Zionism, which is the idea of creating a Jewish state.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Harold Laski was born in Manchester, England, on June 30, 1893. His father, Nathan Laski, was a cotton merchant from Lithuania. His mother, Sarah, was born in Manchester. Harold had an older brother, Neville, and a younger sister, Mabel.

He went to the Manchester Grammar School. In 1911, he studied eugenics for six months at University College London (UCL). That same year, he married Frida Kerry. She was a lecturer in eugenics and was eight years older than him. His family was upset because Frida was not Jewish. Laski also stopped believing in Judaism.

He then studied history at New College, Oxford, and finished in 1914. He won a special prize called the Beit memorial prize. During this time, he supported women's suffrage, which was the right for women to vote. He was not able to fight in World War I because he failed his medical tests. After college, he worked briefly for a newspaper called the Daily Herald. His daughter, Diana, was born in 1916.

Academic Career

In 1916, Laski became a lecturer at McGill University in Canada. He also taught at Harvard University and Yale University in the United States. He supported the Boston Police Strike in 1919, which caused some criticism. He also helped start The New School in 1919.

Laski made many friends in America, especially at Harvard. He often gave lectures there and wrote for The New Republic magazine. He became good friends with important people like Felix Frankfurter and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.. He and Holmes wrote letters to each other every week, which were later published. Laski was known for sometimes exaggerating his connections. His wife said he was "half-man, half-child, all his life."

Laski moved back to England in 1920. He started teaching government at the London School of Economics (LSE). In 1926, he became a professor of political science there. He was also part of the Fabian Society, a socialist group, from 1922 to 1936. In 1936, he helped create the Left Book Club. He wrote many books and essays throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

At the LSE, Laski connected with scholars from the Frankfurt School. These scholars had to leave Germany when Adolf Hitler came to power. Laski helped them set up an office in London. He also helped Franz Neumann, a political scientist, join the Institute.

A Popular Teacher

Laski was a very good lecturer. However, he sometimes made students feel bad if they asked questions. Despite this, his students liked him a lot. He was especially popular with students from Asia and Africa who studied at the LSE.

Kingsley Martin, a writer, described Laski's teaching style. He said Laski was young but gave brilliant lectures without notes. He often linked old ideas to current events.

Another student, Ralph Miliband, praised Laski's teaching. He said Laski taught them that ideas were important and learning was exciting. His classes taught students to be tolerant and listen to different opinions. Miliband felt Laski loved students because they were young and full of hope. He believed that by helping young people, Laski was helping to build a better future.

His Ideas and Beliefs

Laski's early work focused on pluralism. He believed the government should not be the only powerful group. People should also be loyal to local groups like clubs and unions. He thought the government should respect these groups and encourage decentralization.

Later, Laski became a supporter of Marxism. He believed in a planned economy where the government owned major industries. He thought that a truly fair society might not be possible without some violence. This was because he believed rich people would not give up their power easily. However, he also strongly believed in civil liberties, like free speech and representative democracy.

At first, he hoped that the League of Nations would create a global democratic system. But by the late 1920s, his views became more extreme. He felt it was necessary to move beyond capitalism. He was upset by the agreement between Germany and the Soviet Union in 1939.

During World War II, Laski strongly supported the Allies. He encouraged American support for the war effort. He wrote many articles and gave lectures in the US. In his later years, he was sad about the Cold War. George Orwell described him as "A socialist by allegiance, and a liberal by temperament."

Laski tried to get academics and teachers in Britain to support socialism. He had some success, but his ideas were often not fully accepted by the Labour Party.

Political Involvement

Laski's main political role was as a writer and lecturer. He spoke and wrote about many topics important to socialists. These included socialism, capitalism, working conditions, women's suffrage, and human rights. He worked tirelessly to help Labour Party candidates. He also served on many committees and was a full-time professor.

When he returned to London in 1920, he quickly joined Labour Party politics. In 1923, he turned down offers to become a Member of Parliament or join the cabinet. He felt that a peaceful change to socialism would be stopped by opposing forces. In 1932, Laski joined the Socialist League, a left-wing group within the Labour Party. From 1934 to 1945, he served on the Fulham Borough Council.

In 1937, the Socialist League was no longer supported by the Labour Party. Laski was elected to the Labour Party's National Executive Committee. He stayed on this committee until 1949. He led the Labour Party Conference in 1944 and was the party's chairman from 1945 to 1946.

Loss of Influence

During World War II, Laski supported Prime Minister Winston Churchill's government. He gave many speeches to encourage the fight against Nazi Germany. He worked too much and became very stressed. During the war, he often argued with other Labour figures and with Churchill. He slowly lost his influence.

In 1942, he wrote a Labour Party pamphlet. It called for Britain to become a socialist state after the war. This meant the government would keep control over the economy.

In the 1945 general election, Churchill warned that Laski would be the real power behind a Labour government. Laski made a speech where he said that if Labour didn't get what it needed peacefully, they might have to use violence. This caused a big stir. The Conservatives attacked the Labour Party for Laski's words. Laski sued a newspaper, the Daily Express, for saying he supported violence. But the court case showed that Laski had often talked about "revolution" in the past. The jury sided with the newspaper.

After the election, Clement Attlee became Prime Minister. He gave Laski no role in the new Labour government. Laski had called Attlee "uninteresting" in the American press. He even tried to get Attlee to resign. He also tried to make foreign policy decisions for the new government. Attlee strongly told him off, saying Laski had no right to speak for the government. Attlee said there was "widespread resentment" in the party about Laski's actions.

Even though he kept working for the Labour Party, Laski never got his political influence back. He became more pessimistic. He disagreed with the government's policies against the Soviet Union during the early Cold War.

Death

Harold Laski caught influenza and died in London on March 24, 1950. He was 56 years old.

Legacy and Impact

Laski's biographer, Michael Newman, said that Laski wrote too much. He also thought Laski sometimes confused analysis with strong opinions. But Newman said Laski was a serious thinker and a very interesting person. His views were sometimes misunderstood because he didn't agree with common ideas during the Cold War.

Laski had a big impact on supporting socialism in India and other countries in Asia and Africa. He taught many future leaders at the LSE, including Jawaharlal Nehru, who became India's first Prime Minister. John Kenneth Galbraith, a famous economist, said that Laski was central to Nehru's thinking. He also said India was the country most influenced by Laski's ideas. Because of Laski, the LSE is very famous in India. He strongly supported independence of India.

Indian students at the LSE admired him greatly. One Indian Prime Minister even joked that Laski's "ghost" had a chair reserved in every Indian Cabinet meeting. Laski recommended K. R. Narayanan (who later became President of India) to Nehru. This led to Narayanan joining the Indian Foreign Service. In Laski's memory, India created The Harold Laski Institute of Political Science in 1954.

Nehru praised Laski at a meeting in London in 1950. He said Laski was a "lover of freedom" and thanked him for his strong support for India's freedom. He said Laski never gave up on his beliefs and inspired many people.

Laski also taught Chu Anping, a Chinese intellectual and journalist. Anping was later punished by the Chinese Communist government.

Laski was an inspiration for a character in Ayn Rand's novel The Fountainhead. Rand even changed the character's appearance to match Laski after hearing him lecture.

Laski's writing style could be difficult to understand. George Orwell used one of Laski's sentences as an example of poor writing. However, many Labour Members of Parliament elected in 1945 had been taught by Laski. When Laski died, a Labour MP named Ian Mikardo said Laski's goal was to turn the idea of human brotherhood into political economy.

Images for kids

-

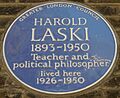

Blue plaque, 5 Addison Bridge Place, West Kensington, London

See also

In Spanish: Harold Laski para niños

In Spanish: Harold Laski para niños

- American studies in the United Kingdom

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |