Florina facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Florina

Φλώρινα

|

||

|---|---|---|

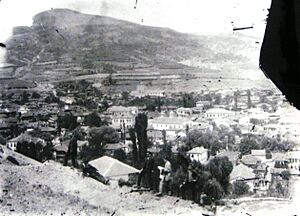

View of the city of Florina towards the NE

|

||

|

||

| Country | Greece | |

| Administrative region | Western Macedonia | |

| Regional unit | Florina | |

| Area | ||

| • Municipality | 819.7 km2 (316.5 sq mi) | |

| • Municipal unit | 150.6 km2 (58.1 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 687 m (2,254 ft) | |

| Population

(2021)

|

||

| • Municipality | 29,500 | |

| • Municipality density | 35.99/km2 (93.21/sq mi) | |

| • Municipal unit | 19,198 | |

| • Municipal unit density | 127.48/km2 (330.16/sq mi) | |

| Community | ||

| • Population | 17,188 (2021) | |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) | |

| Postal code |

531 00

|

|

| Area code(s) | 23850 | |

| Vehicle registration | ΡΑ* | |

| Website | http://www.cityoflorina.gr | |

Florina (Greek: Φλώρινα, Flórina) is a town and a municipality in the mountains of northwestern Macedonia, Greece. Its motto is, 'Where Greece begins'.

The town of Florina is the main city of the Florina regional area. It is also the center of the Florina municipality. It is part of the administrative region called Western Macedonia. The town has about 17,188 people living there (2021 count). It is in a wooded valley about 13 km (8 mi) south of the border with North Macedonia.

Contents

- Exploring Florina's Location and Landscape

- The Name of Florina

- Florina's Municipality and Divisions

- A Look at Florina's Past

- Getting Around Florina: Transport

- Florina's Economy and Daily Life

- Important Places and Buildings in Florina

- Florina's Diverse Population

- Famous People from Florina

- Images for kids

- See also

Exploring Florina's Location and Landscape

Florina is a key entry point to the beautiful Prespa Lakes. It is located west of Edessa and northwest of Kozani. It is also northeast of Ioannina and Kastoria cities. Close to Greece's borders, it is near Korçë in Albania and Bitola in North Macedonia. The closest airports are to the east and south (in Kozani). The Verno mountains are to the southwest. The Varnous mountains are to the northwest.

Winters in Florina bring lots of snow. Temperatures often stay below freezing for long periods. The town and its valley are usually covered in thick fog during winter. This fog can sometimes last for weeks. In summer, Florina becomes a busy market town. Its economy gets a boost from tourism. This is especially true in winter because of the heavy snow and nearby ski resorts.

Florina had one of the first rail lines in the southern Ottoman areas in the late 1800s. However, its rail system is still not fully developed. Today, Florina is connected by a single train track to Thessaloniki and Bitola. It also connects to Kozani. A new A27 motorway runs east of Florina. The part from Florina to Niki has been open since 2015.

Florina's Unique Climate

Florina is one of the coldest towns in Greece. This is because of its high elevation and location. Heavy snowfalls, thick fog, and freezing temperatures are common in winter. Summers are warm to hot. Florina has a climate that is humid subtropical, almost humid continental.

The Big Cold Snap of 2012

In January 2012, Florina experienced a very cold period. On January 18, the official weather station recorded a temperature of -25.1 °C. Some local reports even mentioned temperatures as low as -32 °C in nearby villages. From January 16 to 19, temperatures stayed below -20 °C. The average high temperature for January was only -0.6 °C. For 13 days in a row, temperatures never went above 0 °C. Because of this extreme cold and heavy snow, the Florina municipality was declared a state of emergency on January 16, 2012.

| Climate data for Florina (1961–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.7 (65.7) |

23.0 (73.4) |

25.8 (78.4) |

31.2 (88.2) |

33.8 (92.8) |

39.0 (102.2) |

40.8 (105.4) |

38.6 (101.5) |

36.0 (96.8) |

32.2 (90.0) |

26.6 (79.9) |

22.3 (72.1) |

40.8 (105.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 4.7 (40.5) |

7.4 (45.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

16.8 (62.2) |

22.0 (71.6) |

26.4 (79.5) |

29.0 (84.2) |

29.0 (84.2) |

24.7 (76.5) |

19.0 (66.2) |

12.2 (54.0) |

5.9 (42.6) |

17.4 (63.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.6 (33.1) |

2.8 (37.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

11.7 (53.1) |

16.9 (62.4) |

21.1 (70.0) |

23.4 (74.1) |

22.8 (73.0) |

18.2 (64.8) |

12.9 (55.2) |

7.2 (45.0) |

2.0 (35.6) |

12.2 (54.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.1 (26.4) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

1.5 (34.7) |

5.4 (41.7) |

9.5 (49.1) |

12.8 (55.0) |

14.8 (58.6) |

14.7 (58.5) |

11.4 (52.5) |

7.1 (44.8) |

2.6 (36.7) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

6.1 (43.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.1 (−13.2) |

−23.0 (−9.4) |

−13.6 (7.5) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

2.4 (36.3) |

6.6 (43.9) |

4.0 (39.2) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−12.6 (9.3) |

−18.6 (−1.5) |

−25.1 (−13.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 56.8 (2.24) |

51.1 (2.01) |

57.8 (2.28) |

60.4 (2.38) |

59.4 (2.34) |

37.3 (1.47) |

33.9 (1.33) |

30.6 (1.20) |

50.1 (1.97) |

69.2 (2.72) |

71.3 (2.81) |

85.6 (3.37) |

663.5 (26.12) |

| Average precipitation days | 11.0 | 10.6 | 11.1 | 10.6 | 10.7 | 7.2 | 5.5 | 5.3 | 6.5 | 7.6 | 9.7 | 11.8 | 107.6 |

| Average snowy days | 7.5 | 6.3 | 4.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.8 | 5.9 | 27.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 81.2 | 76.4 | 68.8 | 63.2 | 62.8 | 58.6 | 55.4 | 56.9 | 63.3 | 71.4 | 77.8 | 81.7 | 68.1 |

| Source: Hellenic National Meteorological Service | |||||||||||||

The Name of Florina

The city's old Byzantine name was Chlérinon. This name meant "full of green vegetation." It came from the Greek word chlōrós, meaning "fresh" or "green." Later, the name was sometimes written as Florinon. This came from the Latin word flora, meaning "vegetation." In early Ottoman records, both Chlerina and Florina were used. Florina became the common name after the 1600s. The local Slavic name for the city is Lerin. This name came from the Byzantine Greek name. The Albanian name is Follorinë. In Aromanian, it is Florina. In both Bulgarian and Macedonian, it is Lerin.

Florina's Municipality and Divisions

The current municipality of Florina was created in 2011. It was formed by combining four older municipalities. These four areas became municipal units:

- Florina

- Kato Kleines

- Meliti

- Perasma

The total area of the municipality is about 819.7 square kilometers. The Florina municipal unit itself covers about 150.6 square kilometers.

Communities in Florina's Municipal Unit

The Florina municipal unit is further divided into smaller communities:

- Alona

- Armenochori

- Florina

- Koryfi

- Mesonisi

- Proti

- Skopia

- Trivouno

A Look at Florina's Past

An ancient settlement called Melitonus was once in the Florina area. Today, you can still find remains of a Hellenistic era settlement on Agios Panteleimon hill. Archaeologists first dug here in the 1930s. They found mostly homes. The items found show that people lived here from the 4th century BC until a fire in the 1st century BC. Many of these finds are now in the Archaeological Museum of Florina.

The town, with its current name, is linked to the Byzantine name Chloron. It was first mentioned in 1334. By 1385, the area was taken over by the Ottomans. An Ottoman record from 1481 shows a settlement with 243 households.

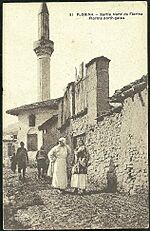

The Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi visited Florina in the 1600s. He wrote that Florina had six neighborhoods and 1500 homes. It also had mosques, schools, bathhouses, and inns. Under Ottoman rule, Florina was an important center for trade and government.

Florina and its people played a big part in the Macedonian Struggle. This was a fight for the region's future.

The Balkan Wars (1912-1913) ended Ottoman rule. Florina and the surrounding area became part of Greece in November 1912. In 1916, Florina became a battleground during World War I. It was occupied by Bulgaria and later taken back by the French army.

During the Axis Occupation in World War II, Florina was under German control. It became a center for Slavic groups who wanted to separate.

For part of the Greek Civil War (1946–1949), the Florina mountains were controlled by communists. Many Slav Macedonians in the area joined the communist army. In February 1949, the Greek National Army defeated an attempt by the communist army to take over Florina. Thousands of communists and Slav Macedonians left or fled to Yugoslavia and other Eastern Bloc countries after the communists were defeated.

Getting Around Florina: Transport

Train Travel

The city has the Florina station. It is on the Thessaloniki–Bitola line. Local trains connect Florina to Thessaloniki.

Florina's Economy and Daily Life

Florina is a market town. Its economy mainly relies on farming and forestry. Tourism, both in summer and winter, is also very important. People also trade across the border. Local products like grain, grapes, and vegetables, including Florina peppers, are sold. The town also has textile factories. It is known for its handmade leather items.

A very large lignite mine is the most important industrial activity. Lignite is a type of coal.

Florina's university became part of the University of Western Macedonia in 2002. Before that, it was a branch of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.

Florina has 8 radio stations and 2 daily newspapers. It also has 4 weekly newspapers and two sports newspapers.

In the 1950s and 1960s, many people left Florina. They moved to Athens and Thessaloniki. Many also moved to the US, Canada, Australia, and Germany. After Greece joined the EU and the economy improved, many people returned from Germany.

In 2016, a new part of the A27 motorway opened. It connects Florina to the border with North Macedonia.

Important Places and Buildings in Florina

For five centuries, Florina had a Muslim community. They built many public and religious buildings. These included mosques, bathhouses, a clock tower, and Ottoman mansions. Most of these buildings were taken down in the 1900s. For example, seven mosques were demolished. The town's bank now stands where a Tekke (a type of religious building) used to be.

Other Ottoman landmarks were also removed. The clock tower in the town center was taken down in 1927. A bathhouse was demolished in 1925. The Muslim Cemetery was also destroyed to make way for a new town plan. One old bathhouse from the late 1500s or early 1600s still exists. It was used until 1958. A fortification tower called the Koula also remains, but it is in poor condition. Most Muslim monuments were destroyed in the 1900s. After the 1960s, almost all signs of the Muslim presence disappeared. Some Ottoman landmarks that are still in good condition are the prison, built in the early 1900s, and the administration building from 1904. This building is now used for Florina's courts.

After Florina became part of Greece, a new town plan was made. This plan aimed to modernize the town. Many sites linked to different past cultures, like mosques, synagogues, and cemeteries, disappeared. After World War Two, there were no traces left of the Jewish cemetery. The Cathedral of St. Panteleimon was built in 1870. It had Slavic architectural styles. In 1971, the Cathedral was torn down because it was considered unsafe.

A Bulgarian school was built in Florina between 1905 and 1908. It was used until 1913. This building was used for different purposes over the years. It was a Greek high school twice. It was also used by the French, Germans, and the Greek National Army during wars. Later, it became a Commercial School. The government thought about saving the building to house the Art Museum of Florina. However, the school was torn down in late 1978. The local authorities and the Archbishop of Florina supported this. A new high school was built on the site.

In the early 2000s, Florina had over 40 monuments. These included sculptures, statues, and busts. They showed or referred to the town's history. This included the struggle over Macedonia, World War II, and the Civil War in Greece. Many monuments of fighters and politicians were placed after 1960. These marked the success of Greek efforts. In George Modis town square, there are busts of important figures. These monuments were put up to help local people feel more connected to Greek identity. Other monuments in the square include a statue of freedom and a memorial to Greek soldiers who died in the Greek-Italian War. Florina also has a military cemetery for Greek soldiers from the Civil War.

In the mid-2000s, two attempts to build a memorial for communist fighters were destroyed. In 2009, the Greek Communist Party bought the site. In 2016, they built a memorial there. In 2005, three marble copies of old funeral monuments were placed in the town center. The original ancient Greek and Roman monuments are in the Florina Archaeological Museum. Some local people have tried to show Florina's history from the Ottoman period. They have done this through exhibitions and films.

- Archaeological Museum of Florina

- Florina Museum of Modern Art

- The Florina Art Gallery

- Folklore Museum of the Aristotle Association

- Folklore Museum of the Culture Club

Florina's Diverse Population

Under Ottoman rule, Florina's population included Muslims, Greeks, Jews, Slavophones (people who speak Slavic languages), and Romani people.

An Austrian diplomat visited Florina in 1861. He wrote that about half the population were Albanian and Turkish Muslims. The other half were Christian Bulgarians. In 1878, a French book said Florina had 1,500 households. It had 2,800 Muslims and 1,800 Bulgarians.

In 1896, a traveler named Victor Bérard visited Florina. He said it had 1,500 houses. These were made up of Albanians and "converted Slavs." There were also 100 Turkish families and 500 Christian families. Bérard wrote that these Slavs called themselves Greek and spoke Greek.

A Jewish Sephardi community was in Florina during the 1600s. Under Ottoman rule, Florina's Jews were close to the Jewish community in Monastir (now Bitola). Romani people also moved to Florina from Anatolia.

After Florina became part of Greece, its population was about 10,000. Two-thirds were Muslim. Many Christian people in Florina spoke Slavic languages. There were also Aromanian families and Greek refugee families from other areas.

In 1916, a Greek diplomat wrote that Florina had 10,392 people. This included 6,227 Muslims, 3,576 Greeks, and 589 former Exharchists.

After the Balkan Wars (1912-1913), many Aromanian people from Monastir moved to Greece. Many settled in Florina. In the late 1920s, a new neighborhood was built for about 600 Aromanian refugee families. During World War I, 60 Jewish families moved to Florina from Monastir to avoid shelling.

The 1920 Greek census counted 12,513 people in the town. In 1923, 4,650 people (1,076 families) were Muslim. During the Greek–Turkish population exchange (1923), Muslim Albanians from Florina were sent to Turkey. They mostly settled in Bursa. After this exchange, Greek refugee families in Florina came from East Thrace, Asia Minor, Pontus, and the Caucasus. The 1928 Greek census recorded 10,585 town residents. In 1928, there were 178 refugee families (750 people) and about 500 Jewish people. The town remained diverse, with Slavophones, Jews, and Romani people.

Local Jews were involved in Florina's economy. They worked in textiles, farming, and raw materials. In World War II, Florina was occupied by Germany. In April 1943, 372 Florina Jews were sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp. They were killed there. In 1945, only 64 Jewish people remained in Florina. This was an 84 percent reduction due to the Holocaust. The Jewish population continued to decline. By 1983, there were no Jews left in Florina.

The Romani people of Florina live in one place. In 1968, they changed from Islam to Orthodox Christianity. Today, Florina Romani people speak Romani. They also speak other languages used in the region. In the late 1990s, the Romani community in Florina was estimated to be about 3,000 people. They lived in a neighborhood on the edge of town.

The Centre for the Macedonian Language in Greece is located in Florina.

| Year | Town | Municipal unit | Municipality |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 12,573 | - | |

| 1991 | 12,355 | 14,873 | - |

| 2001 | 14,985 | 17,500 | - |

| 2011 | 17,907 | 19,985 | 32,881 |

| 2021 | 17,188 | 19,198 | 29,500 |

Famous People from Florina

- Alexis Alexoudis (born 1972), a footballer

- Mary Coustas (born 1964), an Australian actor

- Necati Cumalı (1921–2001), a Turkish writer and poet

- Peter Daicos (born 1961), an Australian Football player; his family is from the Florina region

- Dimitrios Makris (1901–81), a Member of Parliament and Minister

- Pericles A. Mitkas (born 1962), an engineer and university rector

- Nikolaos Pyrzas (1880–1947), a leader during the Macedonian Struggle

- Nadia Tass (active 1979 to present), an Australian director and actor

- Pavlos Voskopoulos (born 1964), a politician and leader of the Rainbow party

- Elpida Karamandi (1920–1942), a partisan fighter

Images for kids

-

House in Florina. Scenery of Angelopoulos film O Melissokomos

See also

In Spanish: Flórina para niños

In Spanish: Flórina para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |