Fortress of Humaitá facts for kids

The Fortress of Humaitá (built between 1854 and 1868) was a very important military base in Paraguay. It was located near where the River Paraguay meets other rivers. People called it the "Gibraltar of South America" because it was so strong. It was seen as "the key to Paraguay" and the rivers that led into the country.

This fortress played a huge part in the Paraguayan War, which was the deadliest conflict in South American history. Humaitá was the main battleground for much of the war.

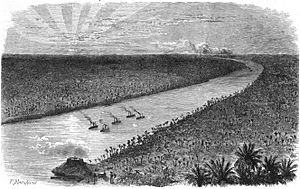

The fortress was built on a sharp bend in the river. Almost all ships wanting to enter Paraguay, or even go further to Mato Grosso in Brazil, had to pass this bend. The bend was protected by a line of cannons about 6,000-foot (1.8 km) long. At one end, there was a huge chain that could be raised to stop ships. This forced them to stay under the fortress's guns. The part of the river where ships could pass was only 200 yards wide, making them easy targets.

The fortress was also safe from attacks on land. It was surrounded by thick swamps. Where there were no swamps, there were strong earthworks (walls of earth). These defenses included a system of trenches stretching for 8 miles (13 km). At its strongest, Humaitá had 18,000 soldiers and 120 cannons. Everyone believed it was impossible for enemy ships to get past Humaitá.

Because Humaitá seemed so strong, Paraguay's leader, Francisco Solano López, might have become too confident. This might have led him to take big risks in his dealings with other countries. He ended up seizing ships and lands from much larger countries like Brazil and Argentina, and sending armies to invade them and Uruguay. These countries then united against him in the Treaty of the Triple Alliance. The war led to Paraguay's complete defeat and ruin, and many lives were lost.

One of the goals of the Treaty of the Triple Alliance was to destroy the Humaitá fortifications so that no such strong forts would be built again. Even though the fortress was not as strong against the newest armored warships, it was still a major problem for the Allies. It stopped their plans to sail upriver to the Paraguayan capital, Asunción, and to take back Brazilian land. Humaitá delayed them for two and a half years. It was finally captured in the Siege of Humaitá in 1868 and then torn down as the treaty demanded.

Today, for Paraguayans, Humaitá is a symbol of national pride. It represents their country's strong will to fight back.

Contents

Why Humaitá Was Built

Key to Paraguay's Safety

Paraguay is a country with no coastline. For most of its history, it was hard to reach, except by sailing from the Atlantic Ocean up the River Paraná and then the River Paraguay. While there were other ways to enter, an invading army would have struggled to get supplies through difficult and unfriendly land. So, controlling the river was vital for Paraguay's safety. Paraguay was always worried about its two much larger neighbors, Brazil and Argentina.

Worries About Brazil

For a long time, there were conflicts between the empires of Portugal (which became Brazil) and Spain (which became Paraguay and Argentina). The Portuguese often moved into Spanish lands. Even after independence, these conflicts continued. Brazil had no easy way to reach its own territory of Mato Grosso except by sailing up the River Paraguay. Paraguay's fear of Brazil blocking this route was a constant source of trouble. The exact border between Paraguay and Brazilian Mato Grosso was also unclear.

Worries About Buenos Aires

The Spanish Viceroyalty of the River Plate was a huge territory that included modern-day Bolivia, Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay. When it became independent from Spain, the city of Buenos Aires claimed to be the capital of this whole area. However, other regions like Bolivia, Uruguay, and Paraguay disagreed and became independent. Buenos Aires did not recognize Paraguay's independence. For example, in 1811, an army from Buenos Aires tried to stop Paraguay from becoming independent but failed. Later, the governor of Buenos Aires, Juan Manuel Rosas, tried to control Paraguay by closing the River Paraná to trade. It wasn't until 1859 that a united Argentina officially recognized Paraguay's independence. Even then, the borders between Argentina and Paraguay were still argued over.

Paraguay's Defensive Mindset

After gaining independence in 1811, Paraguay tried to stay out of the chaos of its neighbors. Its strong leader, José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia (1820–1840), kept the country very isolated. Few people were allowed to enter or leave Paraguay during his rule. This isolation made Paraguayans feel even more nationalistic.

After Francia's death, Carlos Antonio López (the father of Francisco Solano López) became president. He did open Paraguay to foreign trade and new technology. However, the invention of the steamship made his country vulnerable to invasion, and he worried about his powerful neighbors. During his time as president, there were conflicts not only with Brazil and Buenos Aires but also with the United States. Carlos López decided to make Paraguay safe from future foreign attacks.

Why It Was Built Immediately

In 1777, a small fort was built at Humaitá. However, a much bigger version was built step by step under Carlos López's orders. He started the work quickly in 1854 during a conflict with Brazil over borders and river travel. Paraguay was threatened by Brazilian warships. Luckily for López, the Brazilians were delayed because the river was low. Some say López moved 6,000 troops to Humaitá and they worked day and night for 15 days to build up the defenses. The Brazilian ships then decided not to attack because the fort was too strong.

First Construction Work

A Hungarian engineer named Wisner de Morgenstern designed the first defenses. López quickly fortified the river's left bank with cannons. These were slowly added to over time. A trench was dug on the land side to protect the back of the fort. The dense forest was cut down to make way for the first cannon batteries, which took about two years to finish. By 1859, the fort looked very strong. An American eyewitness described it: "Sixteen scary openings pointed their gloom... and seemed to follow the vessel's motion." These were the openings for 16 large cannons. Many other cannon positions were also seen.

British engineers, who were working for the Paraguayan government, helped supervise the ongoing construction.

{{wide image|Humaita in 1857.png|880px|alt=Panorama|A view of the Fortress of Humaitá before the War (scroll horizontally). This drawing from 1857 shows the fortress when it was still being built. The Londres battery with its wide gun openings is on the left. This copy was made by Brazilian naval intelligence.]]

The Finished Fortress

Location

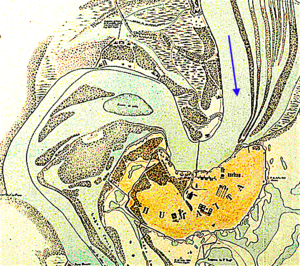

The Humaitá fortress was on a flat cliff about 30 feet (10 meters) above the river. It was located on a very sharp horseshoe bend, called the ‘’’Vuelta de Humaitá’’’, which was a perfect place to control river traffic. This bend was about 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) long. The part of the river where ships could pass narrowed to only 200 metres (660 ft) wide. The river current was strong, making it hard for ships to move forward. Also, the river was perfect for releasing "torpedoes" (old-fashioned floating naval mines).

Ships also faced a tricky surprise: the riverbed had "treacherous backwaters" that could make a ship's steering difficult, especially for longer vessels.

First Look

Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton, an explorer who visited Humaitá during the war, described it like this: "The bend is very curved, which was good for the cannons and bad for ships. Nothing was more dangerous than this big bend, where ships would almost certainly get confused under fire... The flat bank, twenty to thirty feet above the river, is surrounded by swamps both up and downriver. Earthworks, including trenches and other defenses, stretched for nearly eight and a half miles. They enclosed a large area of meadow land, making it a great battlefield."

The River Channel

The 200-yard wide river channel for ships ran very close to the east bank, right next to the fortress's cannons.

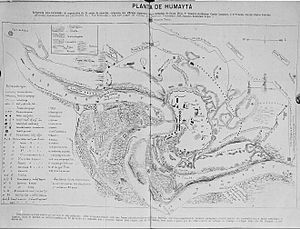

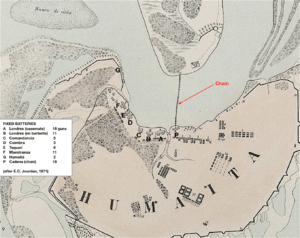

River Cannons

An invading fleet sailing upriver would have to pass eight fixed cannon batteries. All of these could focus their fire on the ships. Also, ships were within range of the heavy cannons long before and after they reached the bend. The names and number of cannons in these batteries changed over time.

First Cannons

First, ships would pass the Humaitá redoubt, which had one large cannon. Then they would face the Itapirú (seven cannons), the Pesada (heavy, five cannons), the Octava or Madame Lynch (three cannons), the Coimbra (eight cannons), and the Tacuarí (three cannons).

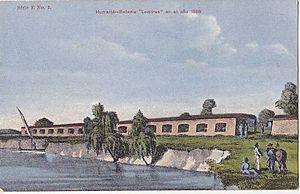

The Londres Battery

Next, the invading fleet would pass the Batería Londres. It was named after the London firm that hired many engineers for Paraguay. Its walls were 8.2 metres (27 ft) thick. It was supposed to be bomb-proof with layers of earth over brick arches. It had openings for 16 cannons. However, some of these openings were walled up and used as workshops because soldiers feared they might collapse.

The Cadenas Battery

Finally, the invading force would reach the Bateria Cadenas (Chain battery), which protected the huge chain boom. This battery had 18 cannons.

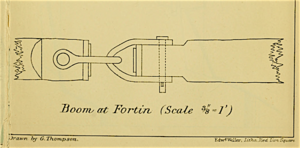

The Chain Boom

The chain stretched across the river to stop ships and hold them under the cannons. Sources describe it differently. Some say it had 7 twisted chains, with the largest link being 1.75 inches thick. It was held by a large windlass on the bank. Other sources say there were three chains side-by-side, with the heaviest links being 7.5 inches. These chains were supported by barges and canoes.

An official report from the Allied forces that captured Humaitá in 1868 stated that there were seven chains on both river banks that joined into three in the water. These were partly held up by large floating iron boxes.

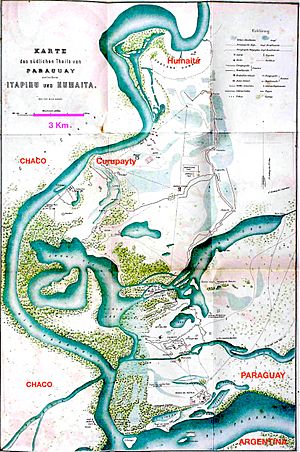

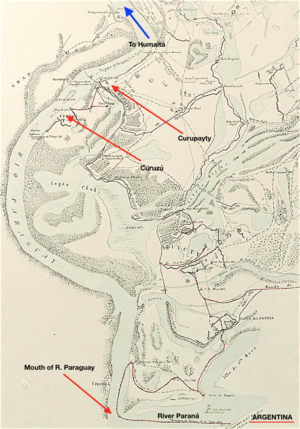

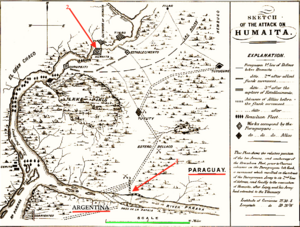

Approach to Humaitá

Before even reaching the Vuelta de Humaitá, an invading fleet had to sail up the River Paraguay from its mouth. They would face cannons the Paraguayans had placed on the river's left bank, especially at Curuzú and Curupayty. Wooden warships never tried to pass these, as they would likely have been sunk.

Even heavily armored ships, called ironclads, were not easily sunk by these river cannons. However, their heavy weight and size made them hard to steer in the shallow waters of the River Paraguay. A British naval officer, Commander Kennedy, noted that the river's depth changed a lot with the seasons. He said, "The danger attendant on grounding in the Paraguay is... [that it] has a sharp rocky bottom." Many Brazilian ironclads needed deep water, so they depended on the river's seasonal rises to move forward or retreat. Their cannons and ammunition were not even loaded until they reached Corrientes, further upriver.

Kennedy also wrote, "It is difficult to imagine a more challenging obstacle to an advancing squadron than this small part of the river between Tres Bocas and Humaitá. The water is shallow, and its depth is very uncertain. The turns in the channel are sharp and frequent, and every available spot was full of heavy cannons."

'Torpedoes'

For invading ironclads, the most dangerous part of Humaitá was not the cannons but the "torpedoes" (improvised contact mines) that could be released in the narrow, shallow river.

These torpedoes were zinc cylinders filled with gunpowder. The largest ones used 1,500 pounds (680 kilos) of gunpowder, and their explosions could shake the ground 20 miles away. The fuses were designed to break a glass capsule of sulfuric acid, which would then ignite a chemical mixture.

Most of these devices failed or went off too early. However, one did sink the 1,000-ton Brazilian ironclad Rio de Janeiro, killing 155 men. So, they were a serious threat. Since a "torpedo" was released almost every night, the Brazilian navy had patrol boats out trying to spot them and hook them with grappling irons. This was a very dangerous job.

Besides the common floating type, Paraguayans also used "torpedoes" anchored to the riverbed, which could not be seen or removed. These created a strong fear among the enemy.

Using these torpedoes was also dangerous for the Paraguayans. The first designer, Mr. Krüger, was blown up by one of his own torpedoes. The next person in charge, Ramos, met the same fate. Then, a Polish refugee named Michkoffsky took over. One day, he was distracted, and the boys paddling his canoe escaped to the Allies with a torpedo. Michkoffsky was arrested and sent to the front lines, where he was soon killed. An anonymous Paraguayan diver even tried to attach a torpedo to the Brazilian ironclad Brasil by hand but drowned after getting tangled in its rudder chains.

The Paraguayans also put empty bottles in the river to make the Brazilian navy think they marked the locations of torpedoes. This made the Brazilians very hesitant to sail in those waters.

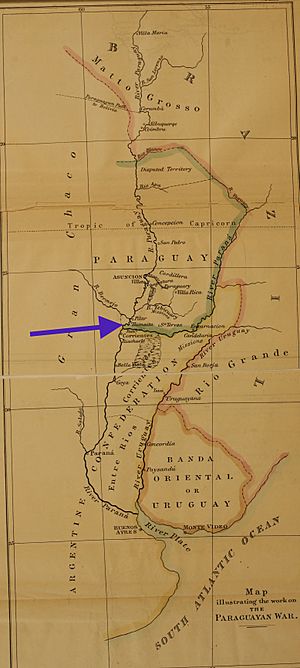

Land Defenses: The Quadrilateral

{{wide image|Humaitá environs and landward defences.png|alt=panorama|880px|The area around and land defenses of Humaitá. This map shows the swamps and trenches that protected the fortress. The thick black lines show the Quadrilateral. The Allies had to find ways around these defenses.]]

Paraguayans also prepared for attacks from the land side. Much of the area was naturally protected by marshes or swamps. Where there were no swamps, a complex system of trenches was built, stretching over 13 km (8 mi). These trenches had wooden fences and sharp obstacles called chevaux-de-fríse at regular spots. This whole system was known as the Quadrilateral. These trenches also had cannons. The map in this section, drawn by Paraguayan army engineer Lt. Colonel George Thompson, shows these defenses.

The Quadrilateral needed at least 10,000 soldiers. At the time of the Siege of Humaitá, the Allied commander thought there were 18,000 to 20,000 soldiers and 120 cannons, not including the river batteries.

Flood Defenses

Colonel George Thompson, the chief engineer, also designed parts of the Quadrilateral to be protected by floods. There was a weak spot at Paso Gómez. By building a dam at another point, he could raise the water level at Paso Gómez by more than 6 feet (2 meters). He also added a sluice-gate. If the enemy tried to attack there, the gate could be opened, releasing a huge flood that would sweep them away into the swamp.

Electric Telegraph

In the later stages of building the fort, electrical telegraph lines were set up from Humaitá and the Quadrilateral points to López's headquarters at Pasó Pucú. This meant López could instantly be told, using Morse code, about any enemy attack. George Thompson noted that the Guaraní people became skilled telegraph operators. "The telegraphs were kept working all day, with division commanders having to report every small detail to López, who received these messages all day long."

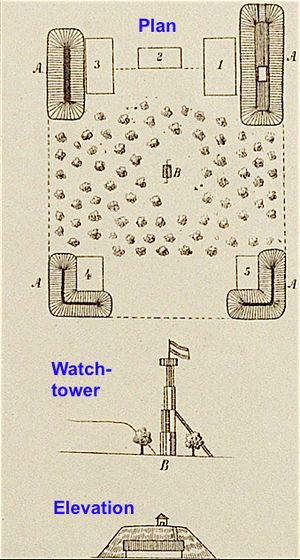

Headquarters

López II set up his headquarters at Paso Pucú, one of the corners of the Quadrilateral. His house, his partner Eliza Lynch's house, and houses for his trusted military officers were there. These were simple houses with thatched roofs. Large earth walls protected his house, Mrs. Lynch's house, and his servants' houses from Allied cannon fire. In the center of this protected area was a mangrullo or watchtower.

A large military hospital was built halfway between Humaitá and Paso Pucú, and another for officers at Paso Pucú itself. There were also two areas for female camp followers who helped in the hospitals and washed clothes. They received no food rations and lived on what the soldiers gave them. There was also a cemetery and a prisoner-of-war camp.

Newspapers

Military newspapers like Cabichuí (in Spanish) and Cacique Lambaré (mostly in Guaraní) were published at the headquarters. These newspapers used simple but strong propaganda, often with offensive drawings. Paper was scarce, so they made a substitute version from caraguatá (wild pineapple).

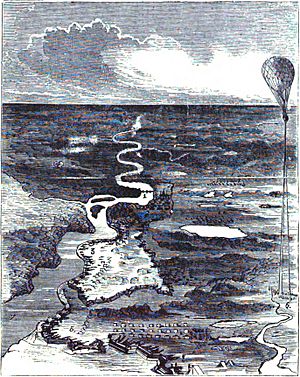

Unmapped Land

While the Paraguayans knew the land well, the Allies had no maps of the area. The region was flat, low-lying, and covered in swamps. For example, when the Allies set up their main camp at Tuyutí, they didn't realize it was within earshot of the Quadrilateral's defenses. They didn't even know Humaitá was protected by the Quadrilateral. A Brazilian historian noted that in 1867, the Allies were completely unaware of the terrain and the Paraguayan trenches.

To map the area, the Allies had to use improvised watchtowers or, for the first time in South American warfare, captive observation balloons. However, the Paraguayans tried to hide the land by lighting fires with damp grass to create smoke.

The Chaco Side

On the opposite bank of the River Paraguay is the Gran Chaco region, which has a different, hot, dry climate. This part of the Chaco was disputed territory and was only inhabited by the fierce Toba nomads. The Chaco bank of the river is low and often floods. The land directly opposite Humaitá was impassable, especially at a place called Timbó, which was completely underwater when the river was high.

Later in the war, when the Allies began to move around Humaitá to the southeast, López sent people to explore the Chaco. He ordered a road to be built through the Chaco from Timbó (the closest place on the opposite bank where a landing could be made). "The road through the Chaco was fairly straight and 54 miles long. It went inland, not along the river. Most of the road went through deep mud, and five deep streams had to be crossed, besides the River Bermejo."

When López realized his position was hopeless, he used this road to escape from Humaitá with most of his troops and cannons. They were ferried from Humaitá to Timbó by two Paraguayan paddle steamers and canoes.

Importance and Reputation

Before armored warships existed, Humaitá was known as an unbeatable fortress. It became famous as the "Sebastopol of South America." During the war, European newspapers compared it to the strongholds of Richmond and Vicksburg in the American Civil War. It was also known in Europe and the United States as the Gibraltar of South America.

Michael George Mulhall, a newspaper editor, visited the site in 1863 and wrote: "A series of powerful cannons glared at us as we passed... Any ship, unless it was armored, trying to force its way through would be sunk by the concentrated fire of this fort, which is the key to Paraguay and the upper rivers."

When Carlos López built Humaitá, all warships were made of wood and mostly powered by paddles. Wooden paddle-steamers trying to enter Paraguay would have had to sail against the current past many cannons, where the distance was 200 meters or less. They would also have to cut through the boom of twisted chains without being sunk. This seemed impossible.

While an army might have been able to invade Paraguay without passing Humaitá, any such attempt would have been very difficult. The only other practical route was through the Upper Paraná River, which was considered too hard by the Allies in 1865.

Professor Whigham, a modern historian, said: "As a strategic location, Humaitá was unmatched in the region, because enemy ships could not go up the Paraguay [river] without passing under its guns. It was also extremely well protected on the south and east by marshes and lagoons. The few dry areas leading to it could be reinforced with troops to stop any attack." Whigham called it "a fortress unlike any seen before in South America."

For Professor Francisco Doratioto, Humaitá and its surroundings were the main battleground of the Paraguayan War.

Weaknesses

In reality, Humaitá was not unbeatable, especially once enough river-navigating ironclad warships became available in South America. After inspecting the captured site, Richard Burton thought its power had been greatly exaggerated—almost like a bluff. The commander of a Portuguese warship there at the time wondered how Humaitá could have stopped a powerful navy for so long.

Poor Weapons

Even though Paraguay could make large cannons, there weren't enough, partly because some had to be moved to strengthen the land defenses. Not all the cannons at Humaitá were good quality. When Burton inspected them in August 1868, he noted that many had been thrown into the river, but the remaining ones were poor. He said, "The cannons barely deserve the name; some were so damaged that they must have been used as street posts." He also mentioned some very old Spanish cannons from the 1600s.

However, Burton might have underestimated the Paraguayan cannons at their peak. According to other sources, some cannons had already been moved by the Paraguayans when they left the fortress. In June 1865, a British gunboat counted 116 cannons at Humaitá, which was far more than Burton or others found after it was captured.

Flawed Fortifications

According to Burton, the fort's design was outdated. It mostly used an old system where the cannons were exposed, which didn't protect the soldiers firing them. This meant: "The defenses were completely unable to withstand the power of modern cannons, concentrated fire from ships, and even accurate rifle fire. The Londres fort, besides being old, was an exposed brick structure that should have been destroyed. If the cannons had been in armored towers or even protected by sandbags, the ironclads would have suffered much more when passing them."

Other observers agreed. Thompson wrote that it should have been easy for the Brazilian fleet to "sweep the Paraguayans away from their guns" with their firing. A British diplomat on a gunboat in 1865 also thought the cannon crews were too exposed. He wrote, "We counted 116 cannons, heavy and light, but all of these, except one heavy battery of 16 guns [the Londres], were exposed, and the crews were completely unprotected from shells, canister shot, or rifle bullets." He also noted that the openings for the cannons in the Londres battery were poorly built, making them easy targets for enemy riflemen.

Becoming Outdated

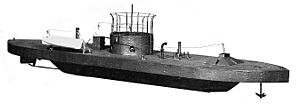

Carlos López built Humaitá when wooden paddle-steamer warships were common. The first ironclad warship, the French Gloire, was launched in 1859, and no battles between European ironclads had happened yet.

However, the American Civil War (1861–65) led to the development of heavily armored ships that could operate in rivers. The Battle of Hampton Roads, where iron-armored Union and Confederate warships couldn't sink each other, showed how strong these ships were. News of this battle reached South America in May 1862. It caused great excitement, as it meant wooden warships were becoming useless.

Besides traditional ironclads, the Americans invented the monitor, an armored, shallow-draft ship with a rotating turret that showed little of itself to enemy fire. Monitors could be built in Brazil. So, by the time López II started the war against Brazil in December 1864, Humaitá's defenses were outdated compared to the latest naval weapons that could be built or bought. Brazil was a huge country and soon had at least 10 ironclads.

However, an ironclad naval force alone was unlikely to threaten Paraguay's entire nation. Even if the latest ironclads could get past Humaitá (which they eventually did), it didn't mean unarmored troopships could. Without the support of an invading army, ironclads couldn't operate far from their supply lines for long.

Loose Chain Boom

Even heavily armored ships might have been slowed by the chain boom, but it had a weak point: it couldn't be pulled tight enough without floating supports in the middle. These supports could be sunk by cannon fire.

Burton described the chain as "seven twisted together." He noted that the large capstan (a machine for winding ropes) on the bank "wanted force to haul tight the chain." This was a problem if the enemy destroyed the floating supports. As Thompson explained, the chains were "supported on a number of canoes, and on three pontoons. The [Brazilian] ironclads fired for three months at these pontoons and canoes, sinking all of them. Then, of course, the chain went to the bottom, as the river there is about 700 yards wide, and the chain could not be drawn tight without intermediate supports. The chain was thus buried some two feet under the mud of the river, offering no obstacle whatever to the navigation."

Supplying the Soldiers

Because the marshlands around Humaitá were not good for raising cattle or growing crops like manioc or maize, and because the Quadrilateral needed many soldiers, food for Humaitá had to be brought in from elsewhere. However, it was very difficult to supply the fort.

Cut off by swamps, there was no easy land route to the nearest food-producing areas. There was a coastal road, but it was poor and not suitable for oxcarts or cattle herds during winter floods. During the war, there was a shortage of steamships, and small river boats were hard to land in winter. "Paraguay never solved these transportation problems during the siege of Humaitá, and the army suffered the consequences," noted Professor Cooney.

Even so, Humaitá withstood a siege for more than two years.

Unexpected Results

The Humaitá system was built to make Paraguay safer. However, its strength, whether real or just believed, might have had the opposite effect in the end.

Angering Brazil

For Brazil, the fortifications were a potential threat to its own safety and caused it to prepare for war. As Lt. Colonel George Thompson of the Paraguayan army noted: "These cannons controlled the entire bend of the river, and Paraguay made all vessels anchor and ask permission before they could pass up the river. Since this was Brazil's only practical route to its province of Matto-Grosso, Brazil naturally disapproved of the river being stopped. Brazil gradually gathered large military supplies in Matto-Grosso, no doubt planning to destroy Humaitá one day."

Causing Overconfidence

Historian Leslie Bethell believes that Solano López overestimated Paraguay's military power, which made him act recklessly. According to Professor Bethell: "Solano López's decision to declare war first on Brazil and then on Argentina, and to invade both their territories, was a serious mistake, and one that would have terrible consequences for the Paraguayan people. At the very least, Solano López took a huge gamble – and lost... Thus, Solano López's reckless actions brought about the very thing that most threatened his country's safety, even its existence: a union of his two powerful neighbors..."

John Hoyt Williams also suggested that Humaitá helped create this risk-taking behavior: "The hundreds of heavy cannons at Humaitá and elsewhere, the modern navy, railroad, telegraph, and weapon factories – all helped bring about the terrible War of the Triple Alliance and their own destruction. They gave Francisco Solano López the tools to become the Marshal and self-appointed leader of the River Plate region." He added that López would not have dared to do more than defend his borders if his military equipment, especially Humaitá, hadn't encouraged him to expand those borders and play a much more dangerous role in the region's power balance.

After the passage of Humaitá, the Buenos Ayres Standard newspaper wrote: "No one who has seen the place has doubted its strength. Old President López had such complete faith in its unbeatable nature that he believed even a Xerxes attacking Paraguay could not get past Humaitá. The same complete confidence in its strength was taught to the Paraguayan people. Their rallying cry was 'Humaitá', and perhaps the current López's exaggerated idea of its strength led to the serious political error that step by step led this unfortunate man away from his father's cautious policy to become the great champion of River Plate balance."

Another View

Another possible idea is that López knew that new developments in naval warfare were making Humaitá outdated. So, he decided to attack before Paraguay lost its advantage completely. Paraguay's chief engineer, William Keld Whytehead, must have known about the benefits of ironclad ships. In 1863, he even got a British patent for an iron-armored ship. In 1857, he had suggested to López that they build ironclads. López himself, just eight months after the Battle of Hampton Roads, was asking the American ambassador to get him a monitor ship. Paraguay even ordered several ironclads to be built in Europe or Brazil before the war.

Further support for this view comes from López's hesitation before seizing the Marques de Olinda ship. According to Thompson:

"López was at Cerro Leon at the time [when the Marques de Olinda arrived at Asunción], and hesitated for a whole day whether he should break the peace or not... He knew he could gather every man in the country immediately and raise a large army. He also knew that the Brazilians would take a long time to gather a large force, and he didn't think they would want to continue a war for long. He said, 'If we don't have a war now with Brazil, we shall have one at a less convenient time for ourselves.' He therefore sent... the 'Tacuarí' (the fastest steamer on the River Plate)... to bring her back to Asunción."

However, none of the sources explain why López declared war without waiting for his ironclads to be finished and delivered. According to Burton, "it was the general opinion" that with just one ironclad, the Paraguayans "would have cleared the river." He even said: "The war, indeed, was completely too early: if the armored ships and modern cannons ordered by the Marshal-President had started the campaign, he might now have created a third great Latin empire, like Mexico."

Instead, early in the war, Paraguay's wooden ships were defeated by a Brazilian wooden fleet at the Battle of the Riachuelo. This led to the River Paraguay being blocked by the Brazilian navy. The armored ships López had ordered could not be delivered or paid for. Brazil then negotiated with the shipbuilders to take over and finish these ships. Brazil eventually used these same ironclads to defeat Humaitá.

The Outcome

A common view is that after the death of the careful Carlos López I, his son did not pay enough attention to his father's advice: to try to settle disputes with Brazil peacefully, not with war. López II was encouraged by the Uruguayan government to get involved in the Uruguayan War. On November 13, 1864, he fired at and seized the Brazilian government ship Marques de Olinda as it sailed upriver. He then went on to seize the Mato Grosso region itself. According to the American ambassador to Paraguay, Charles A. Washburn, López explained his actions by saying "with more honesty than good sense" that only through war could Paraguay gain the world's attention and respect. He believed that even though Paraguay was small compared to Brazil, it had "advantages of position" that made it equally strong. He also thought that Paraguayan troops would be "fortified and entrenched" before the Brazilians could arrive in large numbers.

Encouraged by Brazil's slow response, angered by the Buenos Aires press, and frustrated by Argentina's refusal to let him invade another Brazilian province through Argentine land, López attacked and seized two small Argentine naval vessels in the port of Corrientes on April 13, 1865. He then took over that Argentine province and made Paraguayan money mandatory, with death as punishment for not using it. The resulting War of the Triple Alliance would destroy his country.

Treaty of the Triple Alliance

The Treaty of the Triple Alliance against Paraguay was signed on May 1, 1865. It specifically stated that Humaitá must be destroyed and never rebuilt. Article 18 said that the treaty's terms should be kept secret until its "main goal" was achieved. Some thought this meant the demolition of Humaitá, not just the removal of López. Many political goals are mentioned in the treaty, but no other military ones.

On the same day, the Allied High Command agreed on a strategic plan. Its first point read: The goal of the campaign operations − to which all military operations and invasion routes must be connected − should be the position of Humaitá.

And: "The distance from Paso de Patria [the invasion point] to Humaitá is only seven leagues by land, and whatever the difficulties of the terrain, the short distance, time, and the ability to hit the enemy with the ironclads will make up for it."

How Effective It Was

Despite Burton's criticisms, the Fortress of Humaitá was a serious obstacle to the Allies' plans to move upriver. When it was announced in Buenos Aires that Paraguay had attacked and seized Argentine naval vessels, President Mitre told an angry crowd: "In twenty-four hours we shall be in the barracks, in a fortnight at Corrientes, and in three months at Asunción."

In fact, the Allies did not occupy the Paraguayan capital until January 5, 1869, nearly four years after Mitre's speech. The main reason for this delay was the Humaitá complex.

It might have been "only seven leagues by land" from Paso de Patria to Humaitá, but it was very difficult land to cross. After forcing the Paraguayans out of Argentine soil, the Allies landed in Paraguay and occupied Paso de Patria on April 23, 1866. They did not capture Humaitá until August 5, 1868.

B.C. MacDermot summarized the difficulties: "The terrain gave a huge advantage to the defenders. Below and around Humaitá was a mix of lagoons, marshes, and patches of jungle connected by narrow strips of solid ground. The attacking side had to squeeze through these on a narrow front... An advance inland was only possible at two points: Curupayty to the south and Tayí to the north of Humaitá. Behind the natural defenses were Humaitá's earthworks, with its long outer perimeter reaching Curupaty, and a smaller fort, Timbó, on the Chaco side of the river. To add to their problems, the Allies found that the ironclads were not as effective as they had hoped. They could not move far ahead of their supply lines. The Paraguayan cannons could not sink them, but they could damage them enough to put them out of action. Below the waterline, they were exposed to mines and torpedoes. They could be stopped by underwater obstacles and booms. Their ability to move depended too much on the river's level, which could drop a lot, making the channels narrower and increasing the dangers from obstacles or sandbanks."

"These difficulties are almost enough to explain why the Allies failed to win quickly, despite their huge advantage in numbers and weapons. But they were also held back by divided leadership, national rivalries, and, as time went on, sinking morale. For the Paraguayans, these were the years when their National Epic, as it is called today, was created from countless acts of bravery performed under leaders whose names are known in every home."

Another reason for the delay, according to Professor Williams, was the long pause after the disaster of the Battle of Curupayty. The Allies overestimated the strength of both the opposing army and Humaitá. They allowed López almost a year to rebuild his forces, which had been badly damaged at the Battle of Tuyutí.

The End of Humaitá

On February 19, 1868, when the river was unusually high, six Brazilian ironclad ships were ordered to rush past Humaitá during the night. They did so with little difficulty because the chain boom was already lying on the riverbed. The Paraguayans then stopped getting supplies for Humaitá by river, and the fort was starved out. The fortress was finally captured in the Siege of Humaitá, an operation that ended on August 5, 1868. It was then torn down as required by the Treaty of the Triple Alliance. This was the most important year of the Paraguayan War.

In Books

The second book of Argentine novelist Manuel Gálvez's series Escenas de la Guerra del Paraguay (Scenes from the Paraguayan War) is set in the Fortress of Humaitá.

See also

- Passage of Humaitá

- Siege of Humaitá

- Paraguayan War

- Treaty of the Triple Alliance

- Francisco Solano López

In Spanish: Fortaleza de Humaitá para niños

In Spanish: Fortaleza de Humaitá para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |