Glynn Lunney facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Glynn Lunney

|

|

|---|---|

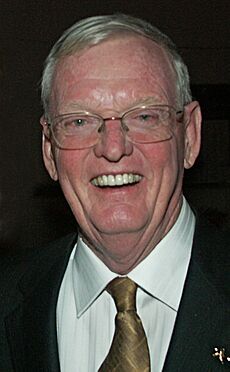

Glynn Lunney in 1974, as manager of the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project

|

|

| Born |

Glynn Stephen Lunney

November 27, 1936 |

| Died | March 19, 2021 (aged 84) Clear Lake, Texas, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | University of Detroit Mercy, B.S. 1958 |

| Occupation | NASA manager and flight director |

| Spouse(s) | Marilyn Kurtz Lunney |

| Awards |

|

Glynn Stephen Lunney (born November 27, 1936 – died March 19, 2021) was an American NASA engineer. He worked for NASA from the very beginning in 1958. Lunney was a flight director during the Gemini and Apollo space programs.

He was on duty during amazing moments like the Apollo 11 moon landing. He also played a key role during the difficult Apollo 13 crisis. After the Apollo program, he led the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project. This was the first time the United States and the Soviet Union worked together in space. Later, he managed the Space Shuttle program. He left NASA in 1985 and became a vice president at United Space Alliance.

Glynn Lunney was very important to the US human spaceflight program. This included missions from Project Mercury to the Space Shuttle. He won many awards for his work. One big award was the National Space Trophy in 2005. Chris Kraft, NASA's first flight director, called Lunney "a true hero of the space age." He said Lunney was "one of the outstanding contributors to the exploration of space."

Contents

Early Life and First Job

Glynn Stephen Lunney was born on November 27, 1936. His hometown was Old Forge, Lackawanna County, Pennsylvania, a coal mining city. He was the oldest son of William and Helen Lunney. His father was a welder and former miner. He encouraged Glynn to get a good education. He wanted his son to find a job outside the mines.

As a child, Glynn loved model airplanes. This led him to study engineering in college. He first attended the University of Scranton. Then he transferred to the University of Detroit. There, he joined a special program. It was run by the Lewis Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio. This center was part of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). NACA was a US agency that studied airplanes.

Students in the NACA program worked and studied at the same time. This helped them pay for college. It also gave them real experience in aviation. Glynn Lunney graduated in June 1958. He earned a degree in aerospace engineering. After graduating, Lunney stayed with NACA. His first job was studying how vehicles heat up when they re-enter Earth's atmosphere at high speeds.

Joining NASA and Early Missions

The Start of NASA

Just one month after Lunney graduated, something big happened. President Eisenhower created the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). NACA became part of NASA. Lunney later said, "there was no such thing as space flight until the month I got out of college." His timing was perfect for a career in space.

In September 1959, Lunney moved to Langley Research Center. He joined the Space Task Group. This group was in charge of creating NASA's human spaceflight program. At 21, he was the youngest of the 45 members. His first job was planning simulations. These simulations trained both flight controllers and astronauts. They needed to prepare for human spaceflight, which was brand new.

Lunney helped plan and create procedures for Project Mercury. This was America's first human spaceflight program. He helped write the first mission rules. These were guidelines for flight controllers and astronauts. During Mercury, Lunney became the second person to be the Flight Dynamics Officer (FIDO). He controlled the spacecraft's path and planned changes to it.

His colleague Gene Kranz said Lunney was a leader in trajectory operations. He turned it from an art into a science. Lunney became a close student of flight director Chris Kraft. Some even called him "the son of Chris Kraft."

Lunney worked in the Control Center and at other locations. During John Glenn's first orbital flight, he was the FIDO in Bermuda. In September 1961, NASA's Space Task Group moved to Houston, Texas. It became the Manned Spacecraft Center. Lunney moved with it. In Houston, he helped set up the computer and display systems for the new Mission Control Center.

Gemini Missions

The Gemini program was a big step forward for NASA. The Gemini capsule was larger than Mercury's. It could carry two astronauts for up to two weeks. Because missions were longer, Mission Control started working in shifts. In 1964, Chris Kraft chose Lunney and Gene Kranz to be flight directors. They joined Kraft and his deputy John Hodge. At 28, Lunney was the youngest of the four flight directors.

Lunney worked on many Gemini missions. He was in Bermuda for the uncrewed Gemini 2 mission. He worked backup on Gemini 3. This was when the new Mission Control Center in Houston was first used. He also worked backup on Gemini 4. This was the first mission fully controlled from Houston. He later became a lead flight director for Gemini 10 and Gemini 12. He also worked as a flight director on Gemini 9 and Gemini 11.

Apollo Missions

Glynn Lunney was involved in Project Apollo from the very start. He led tests of the Apollo escape system. He was also a flight director for the first uncrewed Saturn V rocket test flight.

Lunney was not scheduled to be a flight director for the first crewed Apollo mission, Apollo 1. During a test that led to the Apollo 1 fire, Lunney was at home. He was called into Mission Control when the fire happened. He later said it was "a tremendous punch in the stomach to all of us." Three astronauts died in the fire. Lunney and his colleagues felt they might have become too confident. They were pushing hard to land a man on the Moon by the end of the decade.

Lunney gained a lot of attention in 1968. He was the lead flight director for Apollo 7. This was the first crewed Apollo flight after the fire. It was a very important test for the Apollo program. It was stressful for both astronauts and controllers. Lunney had to deal with the mission commander, Wally Schirra. Schirra often questioned orders from the ground. Lunney remained calm and diplomatic with reporters. But privately, he was frustrated.

As a flight director, Lunney was known for his amazing memory. He also thought very quickly. This could sometimes be hard for his team. A fellow controller, Jay Greene, said Lunney's mind raced so fast. He could give out tasks faster than others could understand them. Lunney was also the lead flight director for Apollo 10. This mission was a practice run for the Apollo 11 Moon landing.

During the Apollo 13 crisis, Lunney played a key role. He came on duty an hour after an oxygen tank exploded. This put the crew's lives in danger. Lunney and his team faced a huge challenge. They had to quickly power up the Lunar Module. They also had to move navigation data from the damaged Command Module. His excellent memory and quick thinking were vital. They helped his team succeed in those critical hours. Ken Mattingly, an astronaut, called Lunney's work "the most magnificent display of personal leadership."

The day after Apollo 13 returned safely, Lunney and his fellow flight directors received an award. They were given the Presidential Medal of Freedom. This was for their work as part of the Apollo 13 Mission Operations Team.

Working with the Soviets: Apollo-Soyuz

In 1970, Lunney was chosen for a special trip. He went to the Soviet Union with a NASA team. They were going to talk about working together in human spaceflight. Lunney was surprised by the news. He said, "For me it was out of the clear blue sky."

The trip happened in late October. In Moscow, Lunney gave a presentation. He explained how NASA brought spacecraft together in orbit. He also talked about what changes would be needed. This was to allow American and Soviet spacecraft to meet. He helped write an agreement. This agreement set the stage for the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project (ASTP). This mission would involve an American Apollo spacecraft docking with a Soviet Soyuz.

The next year, Lunney became the technical director of ASTP. He made several more trips to the Soviet Union. He helped work out a 17-point agreement for the mission. He also worked on technical details in Houston. A newspaper reported he was taking Russian lessons. He wanted to be better prepared for his role.

On June 13, 1972, Lunney became fully in charge of the ASTP. He was responsible for working with the Soviets. He also managed mission planning. In 1973, Lunney became manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office. This gave him more power in leading the ASTP.

The ASTP mission happened in July 1975. Some journalists called it a "costly space circus." They felt it wasted NASA money. But Lunney supported the project. He later said that working together on the International Space Station would not have been possible without ASTP. It laid the groundwork for future cooperation.

Leading the Space Shuttle Program

After the ASTP mission, Lunney became a manager for the Shuttle Payload Integration and Development Program. At this time, NASA expected the Space Shuttle fleet to fly very often. It would carry cargo for businesses and government groups. Lunney's program figured out how to fit different types of cargo into the shuttle's bay. During these years, Lunney also worked at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C.. He held important roles in space transportation operations.

In 1981, Lunney became manager of the Space Shuttle program. This was a very high-level job. He was in charge of planning, budgeting, and scheduling for the program. He also oversaw engineering and mission planning. For early shuttle flights, he helped decide if the weather was safe for launch.

Many of his colleagues thought Lunney would become the director of Johnson Space Center. This was the job his mentor, Chris Kraft, held. But when Kraft retired in 1982, another former Apollo flight director, Gerry Griffin, got the job.

In 1985, Lunney decided to leave NASA. He felt the Space Shuttle program had worn him out. He was ready for a new challenge. Even though he had retired, he was asked to speak to the U.S. House Committee on Science and Technology. This was after the tragic Challenger accident.

Career After NASA

After leaving NASA in 1985, Lunney joined Rockwell International. This company built and maintained the Space Shuttle. He first worked in California. He managed a division that built satellites for the Global Positioning System. This was his first time working with satellites. In 1990, he returned to Houston. He became President of Rockwell Space Operations Company. This company supported flight operations at Johnson Space Center. It had about 3,000 employees. For Lunney, this was a return to his roots in mission operations.

In 1995, Rockwell teamed up with Lockheed Martin. They formed the United Space Alliance. This new company provided support for NASA operations. Lunney became Vice President and Program Manager for spaceflight operations in Houston. He stayed in this position until he retired in 1999.

Personal Life

While working at Lewis Research Center, Lunney met Marilyn Kurtz. She worked there as a nurse. They married in 1960. They had four children: Jennifer, Glynn Jr., Shawn, and Bryan. Their youngest son, Bryan, also worked at NASA. He became a flight director in 2001 and retired in 2011. Glynn and Bryan Lunney were the first father-son flight directors at NASA.

In his free time, Lunney loved sailing. In the 1960s, his family owned a sailboat. They would take it out on Galveston Bay. In retirement, he enjoyed golf. He said, "I have come to realize that golf will not be mastered, but will continue to be humbling."

NASA described Lunney as "legendary." He passed away on March 19, 2021, at his home in Clear Lake, Texas. He was 84 years old. He had been treated for leukemia for several years. But his family said he died from stomach cancer.

Awards and Honors

Glynn Lunney was a Fellow of the American Astronomical Society. He was also a Fellow of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. In 1971, he received an honorary Doctorate from the University of Scranton. He earned many awards from NASA. These included three Group Achievement Awards, two Exceptional Service Medals, and three Distinguished Service Medals.

In 2005, he received the National Space Trophy. This award is given to people who have made huge contributions to America's space program throughout their careers. Previous winners include Chris Kraft and Neil Armstrong. The award foundation said Lunney's "innovation and dedication" set a standard for future space explorers. They added that as a manager, he inspired his employees. He also offered guidance and encouragement during challenges.

In 2008, he received the Elmer A. Sperry Award. He shared this award with Thomas P. Stafford, Alexey Leonov, and Konstantin Bushuyev. They received it for their work on the Apollo–Soyuz mission. This included designing the docking system.

In Films

In the 1995 movie Apollo 13, Glynn Lunney was played by Marc McClure. McClure's role was quite small. Writer Charles Murray felt Lunney was "barely visible in the movie." He said the movie focused too much on Lunney's fellow flight director Gene Kranz. Murray commented that it was Glynn Lunney "who orchestrated a masterpiece of improvisation." This helped move the astronauts safely to the lunar module. Lunney himself said in 2019, "They didn't give me credit for any of the work that I did." He felt he was "sort of portrayed as a flunky."

In the 2020 TV show The Right Stuff, Lunney was played by Jackson Pace.

Images for kids

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |