Ecclesiastical History of the English People facts for kids

The Ecclesiastical History of the English People (in Latin, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum) is a famous history book written by a monk named Bede around the year 731 AD. It tells the story of the Christian Churches in England and the history of England in general. A big part of the book focuses on the differences between the Roman Rite (the way Christians practiced their faith from Rome) and Celtic Christianity (the way Christians practiced their faith in places like Ireland and parts of Britain).

Bede wrote this book in Latin, and he finished it when he was about 59 years old. It's considered one of the most important original sources for understanding Anglo-Saxon history. It also played a key role in helping people in England feel like they belonged to one nation.

Contents

- What the Book is About

- What the Book Covers

- Bede's Purpose in Writing

- How Bede Wrote His History

- Main Ideas in the Book

- What Bede Left Out and His Biases

- The Anno Domini System

- What Happened After Bede's Book

- Why Bede's Book is Important Today

- How Copies of the Book Were Made

- When the Book Was First Printed

- Online Copies and Images

- Important Printed Versions

- See also

What the Book is About

Bede's most famous work, the Ecclesiastical History of the English People, was finished around 731 AD. It has five books.

- The first book starts by describing the geography of England. Then, it quickly covers England's history, beginning with Julius Caesar's invasion in 55 BC. It also briefly talks about Christianity in Roman Britain, including the story of St Alban, a Christian who was killed for his faith. After that, it tells about Augustine's mission to England in 597 AD, which brought Christianity to the Anglo-Saxon people.

- The second book begins with the death of Pope Gregory the Great in 604 AD. It describes how Christianity continued to spread in Kent and the first attempts to bring the faith to Northumbria. There was a setback when Penda, a pagan king, killed the Christian king Edwin of Northumbria around 632 AD.

- But this setback didn't last long. The third book explains how Christianity grew in Northumbria under kings Oswald and Oswy. A very important part of this book is the story of the Council of Whitby. This meeting is often seen as a major turning point in English history, where the Roman way of Christianity was chosen over the Celtic way.

- The fourth book starts with Theodore becoming the Archbishop of Canterbury. It also tells about Wilfrid's efforts to bring Christianity to the kingdom of Sussex.

- The fifth book brings the story up to Bede's own time. It includes details about missionary work in Frisia and the ongoing disagreement with the British church about the correct date for Easter.

Bede wrote a special introduction for his book, dedicating it to Ceolwulf, who was the king of Northumbria. Bede mentions that King Ceolwulf had already seen an earlier version of the book. This shows that Bede's monastery had good connections with important people in Northumbria.

What the Book Covers

The Historia is divided into five books, which together are about 400 pages long. It covers the history of England, both church-related and political, from the time of Julius Caesar up to 731 AD, when Bede finished it.

- Book 1: From the late Roman Republic to 603 AD.

- Book 2: From 604 AD to 633 AD.

- Book 3: From 633 AD to 665 AD.

- Book 4: From 664 AD to 698 AD.

- Book 5: From 687 AD to 731 AD.

The first 21 chapters talk about the time before Augustine's mission. Bede gathered this information from earlier writers and old stories. For the time after 596 AD, Bede used official documents he found across England and from Rome. He also used stories told by people, carefully checking if they seemed true.

Bede's Purpose in Writing

Bede wrote the Ecclesiastical History not just to tell a story, but also to share his own ideas about politics and religion.

He strongly supported his home region of Northumbria. He made sure to highlight Northumbria's importance in English history, often more than its rival, Mercia. He spent more time describing events from the 600s, when Northumbria was very powerful, than from the 700s, when it was less so. The only time he criticized Northumbria was when writing about King Ecgfrith's death in a battle against the Picts in 685 AD. Bede believed this defeat was God's punishment because Northumbria had attacked the Irish the year before.

Even though Bede was loyal to Northumbria, he had an even stronger connection to the Irish and their missionaries. He thought they were much more effective and dedicated than the English missionaries, who he felt were a bit too comfortable.

Bede was also very concerned about the exact date of Easter. He wrote a lot about this topic. It was here that he gently criticized St Cuthbert and the Irish missionaries for celebrating Easter at what he believed was the wrong time. In the end, he was happy that the Irish Church eventually accepted the correct date for Easter.

How Bede Wrote His History

Bede got ideas for his writing style from some of the same authors he used for information. His introduction is similar to the work of Orosius, and his title sounds like Eusebius's Historia Ecclesiastica. Bede also followed Eusebius by using the Acts of the Apostles as a guide for his whole book. Just as Eusebius used Acts to describe the church's growth, Bede used it as a model for his history of the Anglo-Saxon church.

Bede often included long quotes from his sources in his story, just like Eusebius did. Sometimes, he even seemed to use exact words from people he corresponded with. For example, he usually called the South and West Saxons "Australes" and "Occidentales," but in one part, he used "Meridiani" and "Occidui," perhaps because that's what his informant said. At the end of his book, Bede added a short note about his own life. This idea came from Gregory of Tours' earlier History of the Franks.

Bede's work as a writer of saints' lives (a hagiographer) and his careful attention to dates helped him greatly in writing the Historia Ecclesiastica. His interest in computus, which was the science of calculating the date of Easter, was also very useful when he wrote about the disagreement between the British and Anglo-Saxon churches over the correct Easter date.

Main Ideas in the Book

One important idea in the Historia Ecclesiastica is that the conversion of Britain to Christianity was mostly done by Irish and Italian missionaries. Bede suggested that the native Britons didn't do much to spread the faith. He got this idea from another writer, Gildas, who criticized the native rulers. Bede added that the invasion of Britain by the Angles and Saxons was God's punishment because the Britons didn't try to spread Christianity and refused to accept the Roman date for Easter. Even though Bede talks about Christianity in Roman Britain, it's interesting that he doesn't mention the missionary work of St Patrick.

He spoke highly of Aidan and Columba, who came from Ireland to be missionaries to the Picts and Northumbrians. However, he didn't approve of the Welsh people's failure to convert the invading Anglo-Saxons. Bede was a strong supporter of Rome. He saw Gregory the Great, rather than Augustine, as the true apostle (messenger) of the English. Similarly, when he discussed the conversion of the invaders, he played down any involvement of native Britons. For example, when talking about Chad of Mercia's first consecration as a bishop, Bede mentions that two British bishops took part, which he said made it invalid. He didn't give any more information about who these bishops were or where they came from. Bede also saw the conversion process as something that happened mostly among the upper classes, with little talk about missionary efforts among ordinary people.

Another historian, D. H. Farmer, believes the main idea of the book is "the progression from diversity to unity." He thinks Bede showed how Christianity brought different native and invading groups together into one church. Farmer points to Bede's strong interest in the disagreement over the Easter date and his detailed description of the Synod of Whitby as proof. The Synod of Whitby is seen as the central event of the whole book.

Historian Walter Goffart says that many modern historians see the Historia as a story of how a people moved from paganism to Christianity, guided by God. It features saints instead of just warriors, shows amazing historical writing for its time, and has beautiful language. Goffart also feels that a major theme of the Historia is about local Northumbrian concerns. He thinks Bede saw events outside Northumbria as less important than northern history.

The Historia Ecclesiastica includes many stories of miracles and visions. These were common in religious stories from that time. However, Bede seemed to avoid telling the most unbelievable tales. He also made almost no claims about miracles happening at his own monastery. Bede certainly believed in miracles, but the ones he included were often about healing or events that could be explained naturally. These miracles were meant to set an example for the reader. Bede clearly stated that his goal was to teach good behavior through history. He said, "If history records good things of good men, the thoughtful reader is encouraged to imitate what is good; if it records evil of wicked men, the devout reader is encouraged to avoid all that is sinful and perverse."

What Bede Left Out and His Biases

Bede didn't seem to have anyone giving him information from the main religious houses in Mercia. His information about Mercia came from places like Lastingham and Lindsey, which were near Northumbria. Because of this, there are clear gaps in his coverage of Mercian church history. For example, he doesn't mention when Theodore divided the large Mercian diocese (church area) in the late 600s. Bede's focus on his own region is clear.

There were definitely things Bede didn't know, but he also said little about some topics he must have been familiar with. For instance, even though Bede talks about Wilfrid's missionary work, he doesn't fully explain Wilfrid's disagreements with Archbishop Theodore of Canterbury or Wilfrid's ambition and rich lifestyle. We only know about these things because other sources, like the Life of Wilfrid, exist. Bede also doesn't mention the English missionary Boniface at all, even though it's unlikely he knew little about him. The last book has less information about the church in his own time than one might expect. A possible reason for Bede's quietness might be his belief that one should not publicly accuse church leaders, no matter their sins. Bede might have found little good to say about the church in his day and chose to remain silent. It's clear he did have faults to find, as his letter to Ecgberht contains several criticisms of the church.

The Historia Ecclesiastica talks more about bishops than about the monasteries in England. Bede does share some insights into monastic life. In book V, he mentions that many Northumbrians were giving up their weapons and joining monasteries "rather than study the arts of war. What the result of this will be the future will show." This hidden comment, another example of Bede being careful when talking about current events, could be seen as a warning. This is especially true given Bede's more direct criticism of fake monasteries in his letter to Ecgberht, written three years later.

Bede's description of life at the courts of the Anglo-Saxon kings includes little of the violence that Gregory of Tours often mentioned at the Frankish court. It's possible that the courts were truly different, but it's more likely that Bede left out some of the violent reality.

The Anno Domini System

In 725 AD, Bede wrote a book called The Reckoning of Time (in Latin, De Temporum Ratione). In this book, he used a dating system similar to the anno Domini era, which is the BC/AD system we use today. This system was created by a monk named Dionysius Exiguus in 525 AD. Bede continued to use this system throughout his Historia Ecclesiastica, and this helped make the system very popular in Western Europe. He specifically used phrases like "in the year from the incarnation of the Lord" or "in the year of the incarnation of the Lord." He never shortened the term like the modern AD. Bede counted anno Domini from Christ's birth.

In this work, he was the first writer to use a term similar to "before Christ." In Book I, chapter 2, he used "before the time of the incarnation of the Lord." However, this specific phrase wasn't very influential. The first widespread use of "BC" (hundreds of times) happened in a book by Werner Rolevinck in 1474.

What Happened After Bede's Book

Some early copies of the Historia Ecclesiastica have extra notes that go past the date Bede finished the book, with the latest entry being from 766 AD. However, most very old copies don't have these extra notes, except for the years 731 to 734. Much of this extra material is also found in Simeon of Durham's chronicle. The rest is thought to come from northern chronicles from the 700s.

The Historia was translated into Old English sometime between the late 800s and about 930 AD. Even though the surviving copies are mostly in the West Saxon dialect, it seems the original translation had features of the Mercian dialect. This suggests it was done by a scholar from or trained in Mercia. People once thought King Alfred of England did the translation, but this is no longer believed.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was started around the same time the translation was made, used a lot of information from the Historia. Bede's book formed the timeline for the early parts of the Chronicle.

Why Bede's Book is Important Today

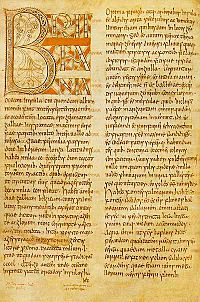

The Historia Ecclesiastica was copied many times during the Middle Ages. About 160 copies of the book still exist today. About half of these are found in Europe, not in the British Isles. Most of the copies from the 700s and 800s come from the northern parts of the Carolingian Empire. This number doesn't include copies that only have a part of the book, of which there are about 100 more. The book was first printed between 1474 and 1482, probably in Strasbourg.

Modern historians have studied the Historia a lot, and many new versions have been published. For many years, early Anglo-Saxon history was basically just a retelling of Bede's Historia. But more recent studies also look at what Bede chose not to write. The old idea that the Historia was the peak of Bede's work, the main goal of all his studies, is no longer accepted by most scholars.

The Historia Ecclesiastica has given Bede a very high reputation. However, his goals were different from those of a modern historian. He focused on the history of the English church and on religious errors and how they were corrected. This led him to leave out the everyday history of kings and kingdoms, unless it taught a moral lesson or explained church events. In the early Middle Ages, other important books like the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Historia Brittonum, and Alcuin's Versus de patribus, regibus et sanctis Eboracensis ecclesiae all used Bede's text a lot.

Later medieval writers, such as William of Malmesbury, Henry of Huntingdon, and Geoffrey of Monmouth, also used his works as sources and inspiration. Writers in early modern times, like Polydore Vergil and Matthew Parker, also used the Historia. Bede's works were used by both Protestants and Catholics during the Wars of Religion.

Some historians have questioned how reliable some of Bede's stories are. One historian, Charlotte Behr, says that the Historia's account of the arrival of the Germanic invaders in Kent should be seen as a popular story from that time, not necessarily a historical fact. Historian Tom Holland writes that when a united kingdom of England was formed after King Alfred, it was Bede's history that gave it a sense of its past, reaching back before its own beginning.

How Copies of the Book Were Made

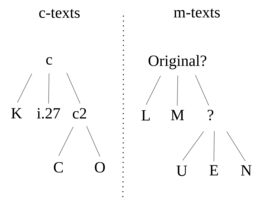

Copies of the Historia Ecclesiastica generally fall into two main groups, which historians call the "c-type" and the "m-type." Historian Charles Plummer found six key differences between these two types of copies. For example, the c-type copies leave out one of the miracles linked to St Oswald in book IV, chapter 14. The c-type also includes the years 733 and 734 in the timeline at the end of the book, while the m-type copies stop at 731.

Plummer thought this meant the m-type was definitely older than the c-type. However, Bertram Colgrave disagreed in his 1969 edition of the text. Colgrave pointed out that adding a few years to a timeline is an easy change for someone copying a book to make at any time. He also noted that leaving out one of Oswald's miracles is not a simple copying mistake, suggesting that the m-type might actually be a later updated version.

We can see how some of the many surviving copies are related to each other. The earliest copies used to figure out the c-text and m-text are listed below:

| Version | Type | Location | Manuscript |

|---|---|---|---|

| K | c-text | Kassel, University Library | 4° MS. theol. 2 |

| C | c-text | London, British Library | Cotton Tiberius C II |

| O | c-text | Oxford, Bodleian Library | Hatton 43 (4106) |

| n/a | c-text | Zürich, Zentralbibliothek | Rh. 95 |

| M | m-text | Cambridge, University Library | Kk. 5. 16 |

| L | m-text | Saint Petersburg, National Library of Russia | Lat. Q. v. I. 18 |

| U | m-text | Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Library | Weissenburg 34 |

| E | m-text | Würzburg, Universitätsbibliothek | M. p. th. f. 118 |

| N | m-text | Namur, Public Library | Fonds de la ville 11 |

Most copies of the Historia Ecclesiastica found in Europe are of the m-type, while copies found in England are of the c-type. Among the c-texts, manuscript K only has books IV and V, but C and O are complete. O is a later copy than C, but it was made independently, so C and O are useful for checking each other. They are thought to have both come from an earlier copy, called "c2" in the diagram, which no longer exists.

The m-text mainly relies on manuscripts M and L, which are very early copies made soon after Bede's death. Both seem likely to have been copied from Bede's original, though this isn't certain. Three other manuscripts, U, E, and N, seem to be copies of a Northumbrian manuscript that no longer exists but was taken to Europe in the late 700s. These three are also early copies, but they are less useful because L and M are already so close to the original.

The text in both the m-type and c-type seems to have been copied accurately. When comparing the earliest copies, Bertram Colgrave found 32 places where there seemed to be a mistake. However, 26 of these mistakes were actually copied by Bede himself from his earlier sources.

History of the Manuscripts

- K was probably written in Northumbria in the late 700s. Only books IV and V survived; the others were likely lost over time.

- C, also known as the Tiberius Bede, was written in southern England in the second half of the 700s.

- O dates to the early 1000s and has corrections from the 1100s.

- L, also known as the St Petersburg Bede, was copied by four scribes no later than 747 AD. The scribes were probably at either Wearmouth or Jarrow Abbey.

- M, also known as the Moore Bede, was written in Northumbria in 737 AD or soon after. This copy was once owned by John Moore, a bishop. King George I bought Moore's collection and gave it to Cambridge University in 1715, where it is still kept.

- U dates to the late 700s and is thought to be a copy, made in Europe, of an earlier Northumbrian manuscript.

- E dates from the middle of the 800s.

- N was copied in the 800s by several scribes.

Copies are rare during the 900s and much of the 1000s. The largest number of copies of Bede's work were made in the 1100s, but there was also a lot of interest in the 1300s and 1400s. Many copies are from England, but surprisingly many are from Europe too.

When the Book Was First Printed

The first printed copy of the Historia Ecclesiastica came out from Heinrich Eggestein in Strasbourg, probably between 1475 and 1480. A small flaw in the text helps us identify the exact manuscript Eggestein used. Eggestein also printed a translation of Eusebius's Ecclesiastical History. These two books were reprinted together on March 14, 1500, by Georg Husner, also in Strasbourg. Another reprint appeared on December 7, 1506.

A Paris edition came out in 1544, and in 1550 John de Grave produced an edition in Antwerp. Two reprints of this edition appeared in 1566 and 1601. In 1563, Johann Herwagen included it in a large collection of his works. Michael Sonnius produced an edition in Paris in 1587, including the Historia Ecclesiastica with other historical works. In 1643, Abraham Whelock produced an edition in Cambridge that had both the Old English text and the Latin text side-by-side. This was the first such edition in England.

All of these early printed editions were based on the C-text manuscripts. The first edition to use the m-type manuscripts was printed by Pierre Chifflet in 1681. For the 1722 edition, John Smith used the Moore MS. and also had access to other copies. This allowed him to print a very high-quality edition. Smith's son, George, finished the work and published it in 1722. Smith's edition was a huge improvement over earlier ones.

Later, the most important edition was by Charles Plummer in 1896. His Venerabilis Bedae Opera Historica, with detailed notes, has been a key resource for all studies since then.

Online Copies and Images

- London, British Library, Cotton MS Tiberius C II, early 800s, Latin: [1]

- Oxford, Bodleian Library MS. Tanner 10, early 900s, Old English: [2]

- Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 041, c. 1000s, Old English: [3]

- Cambridge, University Library, MS Kk.5.16 (The Moore Bede), c.737: [4]

Important Printed Versions

- 1475: Heinrich Eggestein, Strasbourg.

- 1550: John de Grave, Antwerp.

- 1587: Michael Sonnius, Paris.

- 1643: Abraham Whelock, Cambridge.

- 1722: John Smith, Cambridge.

- 1861: Migne, Patrologia Latina (vol. 95), a reprint of Smith's edition.

- 1896: Charles Plummer (editor), Venerabilis Baedae Historiam ecclesiasticam gentis Anglorum, Historiam abbatum, Epistolam ad Ecgberctum una cum Historia abbatum auctore anonymo, 2 volumes (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1896).

- 1969: Bertram Colgrave and R. A. B. Mynors (editors), Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969 [corrected reprint. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991]).

- 2005: Michael Lapidge (editor), Pierre Monat and Philippe Robin (translators), Bède le Vénérable, Histoire ecclésiastique du peuple anglais = Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, Sources chrétiennes, 489–91, 3 volumes (Paris: Cerf, 2005).

- 2008–2010: Michael Lapidge (editor), Paolo Chiesa (translator), Beda, Storia degli Inglesi = Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, Scrittori greci e latini, 2 volumes (Rome/Milan: Fondazione Lorenzo Valla/Arnoldo Mondadori, 2008–2010). This version has a complete critical apparatus (notes on different manuscript readings).

See also