History of Guinea-Bissau facts for kids

Guinea-Bissau has been home to people for thousands of years. In the 1200s, it became part of the powerful Mali Empire. Later, it became its own independent kingdom called Kaabu.

Portugal started claiming the area in the 1450s. For a long time, Portugal only controlled a few forts along the coast. They took full control of the mainland after military campaigns between 1912 and 1915. The Bijago Islands were not colonized until 1936.

After gaining independence in 1974, Guinea-Bissau was ruled by one political party until 1991. Then, new laws allowed many political parties. This led to the first multi-party elections in 1994. However, a civil war happened from 1998 to 1999.

Contents

Ancient People of Guinea-Bissau

The early history of Guinea-Bissau is not fully known from old records. By 1000 AD, people who hunted and gathered food lived there. Soon after, farmers using iron tools arrived.

The oldest groups of people were the Jola, Papels, Manjaks, Balanta, and Biafada. Later, the Mandinka and Fulani moved into the area. They pushed the earlier groups towards the coast.

A few Mandinka people were present as early as the 1000s. But many more arrived in the 1200s. This happened when General Tiramakhan Traore brought Senegambia into the Mali Empire. This led to many people adopting Mandinka culture. The Fulani arrived around the 1100s as herders. However, they did not become a large group until the 1400s.

How People Lived

The Balanta and Jola people had simple leadership. They focused on village and family leaders. The Mandinka, Fula, Papel, Manjak, and Biafada chiefs served kings. Their customs and ceremonies were different. But nobles held all important positions, including in the justice system. People's social status could be seen in their clothes, homes, and how they traveled.

Trade was common among different ethnic groups. They traded things like pepper and kola nuts from the forests. They also traded iron and iron tools from the savannah. Salt and dried fish came from the coast. Mandinka cotton cloth was also traded.

Markets and fairs were held weekly or every eight days. Thousands of buyers and sellers came, some from 60 miles away. Weapons were not allowed in the market. Soldiers kept order throughout the day. Different parts of the market were set aside for specific products.

Pre-Colonial Kingdoms

Kaabu Empire

How Kaabu Began

The Kaabu Empire started in the 1200s. It was first a province of the Mali Empire. This happened after General Tiramakhan Traore conquered Senegambia. Stories say Tiramakhan Traore invaded the region to punish the Wolof king. He then went south of the River Gambia into the Casamance area. This caused many Mandinka to move into the region. By the 1300s, much of Guinea-Bissau was ruled by Mali. It was governed by a farim kaabu (commander of Kaabu).

The Mali Empire slowly became weaker starting in the 1300s. Areas in what are now Senegal, the Gambia, and Guinea-Bissau became separated. This was due to the growing power of Koli Tenguella in the early 1500s. Kaabu then became an independent group of kingdoms. It was the strongest western Mandinka state at that time.

Kaabu Society

Kaabu's rulers were strong warriors called the Nyancho. They believed their family line came from Tiramakhan Troare. The Nyancho were known for being excellent horsemen and raiders. The main leader of Kaabu, the Mansaba, lived in Kansala. Today, this town is called Gabu.

The history of the Mali Empire was very important to Kaabu's culture. Kaabu kept Mali's main ways of life. The Mandinka language was also widely spoken. People from other ethnic groups often adopted this dominant culture. Marriages between different groups helped this process.

The slave trade was a big part of the economy. It made the warrior classes rich. They received imported cloth, beads, metalware, and guns. Trade routes to North Africa were important until the 1300s. Coastal trade with Europeans grew from the 1400s. In the 1600s and 1700s, about 700 enslaved people left the region each year. Many of them came from Kaabu.

Decline of Kaabu

In the late 1700s, the Imamate of Futa Jallon grew powerful to the east. This was a big challenge for Kaabu. In the early 1800s, a civil war started. Local Fula people wanted to be independent. This long conflict led to the 1867 Battle of Kansala.

A Fula army, led by Alpha Molo Balde, surrounded Kansala for 11 days. The Mandinka fought hard but the walls were eventually broken. The Mansaba Dianke Walli, seeing they would lose, ordered his troops to set the city's gunpowder on fire. This killed the Mandinka defenders and most of the invading army. The fall of Kansala marked the end of Kaabu. It led to the rise of Fuladu. Some smaller Mandinka kingdoms survived until Portugal took them over.

Biafada Kingdoms

The Biafada people lived around the Rio Grande de Buba. They had three kingdoms: Biguba, Guinala, and Bissege. Biguba and Guinala were important ports. They had many communities of mixed European and African people. These kingdoms were under the Mandinka mansa (king) of Kaabu.

Kingdom of Bissau

Stories say the Kingdom of Bissau was founded by the son of the king of Quinara (Guinala). He moved to the area with his pregnant sister, six wives, and people from his father's kingdom. At first, relations between Bissau and the Portuguese were friendly. But they became worse over time.

The kingdom strongly fought to keep its independence from Portugal. They defeated Portuguese attacks in 1891, 1894, and 1904. In 1915, the Portuguese, led by Officer João Teixeira Pinto and warlord Abdul Injai, finally took over the kingdom.

Bijagos Islands

The Bijagos Islands had different islands settled by people from various ethnic groups. This created a rich mix of cultures in the islands.

Bijago society was focused on warfare. Men built boats and raided the mainland. They attacked coastal peoples and other islands. They believed they had no king at sea. Women farmed, built houses, and gathered food. They could choose their husbands, usually warriors with the best reputation. Successful warriors could have many wives and boats. They also received one-third of the spoils from any expedition.

Bijago night raids on coastal settlements greatly affected the people they attacked. Portuguese traders on the mainland tried to stop the raids. This was because the raids harmed the local economy. But the islanders also sold many enslaved people to Europeans. Europeans often wanted more captives. The Bijagos themselves were mostly safe from being enslaved. They were out of reach of mainland slave raiders. Europeans avoided having them as slaves. Portuguese records say Bijago children made good slaves. But adults were likely to lead rebellions on slave ships or escape in the New World.

European Contact

1400s–1500s: First Europeans Arrive

The first Europeans to reach Guinea-Bissau were:

- Alvise Cadamosto (Venetian) in 1455

- Diogo Gomes (Portuguese) in 1456

- Duarte Pacheco Pereira (Portuguese) in the 1480s

- Eustache de la Fosse (Flemish) in 1479–1480

The Portuguese called the region 'The Guinea of Cape Verde'. Santiago was the main administrative city. Most white settlers came from there.

Portuguese officials first tried to stop Europeans from settling on the mainland. But this rule was ignored by lançados and tangomãos. These were people who mixed into the local culture and customs. They were often poor traders from Cape Verde or exiles from Portugal. Many had Jewish or New Christian backgrounds. They ignored Portuguese trade rules. These rules banned entering the region or trading without a royal license. They also banned shipping from unauthorized ports or mixing with local communities.

By 1520, Portugal eased rules against the lançados. Trade and settlements grew on the mainland. Portuguese and local traders lived there. Some Spanish, Genoese, English, French, and Dutch people also settled.

The region's rivers had no natural harbors. So, lançados and local traders used small boats. They bought these from European ships or made them locally. Trained grumetes (African sailors, free or enslaved) helped. The main ports were Cacheu, Bissau, and Guinala. Each river also had trading centers like Toubaboudougou. These centers traded directly with the interior for goods like gum arabic, ivory, animal hides, civet, dyes, enslaved people, and gold. A few European settlers set up farms along the rivers. However, local African rulers usually did not let Europeans into the interior. This was to keep control of trade routes.

Europeans were not welcome in all communities. The Jolas, Balantas, and Bijagos were initially hostile. Other ethnic groups in the region had lançado communities. These lançados had to pay taxes and follow local laws and customs. Disputes became more frequent in the late 1500s. Foreign traders tried to influence local societies for their own benefit.

Due to hostile locals, the Portuguese left the settlement of Buguendo near Cacheu in 1580. They also left Guinala in 1583, retreating to a fort. In 1590, they built a fort at Cacheu. The local Manjaks unsuccessfully attacked it soon after. These forts were poorly staffed and supplied. They could not fully free the lançados from their duties to the local kings. The kings themselves could not kick out the traders. This was because the goods they brought were in high demand by the upper class.

Meanwhile, Portugal's trade control was challenged. In 1580, the Iberian Union joined the crowns of Portugal and Spain. This led to attacks on Portuguese areas in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde by Spain's enemies. French, Dutch, and English ships increasingly came to trade with locals and independent lançados.

1600s–1700s: Trade and Challenges

In the early 1600s, the government tried to force all trade through Santiago. They also tried to encourage trade and settlement on the mainland. They restricted selling weapons to locals. These efforts mostly failed.

When the Iberian Union ended in 1640, King João IV tried to stop Spanish trade in Guinea. This trade had grown for 60 years. Afro-Portuguese people in Bissau, Guinala, Geba, and Cacheu promised loyalty to the Portuguese king. But they could not stop the free trade that African kings demanded. African kings now saw European products as necessary. In Cacheu, famine killed the slave troops defending the fort. The water supply remained in Manjak hands. The lançados and their Africanized descendants did not want to lose customers. So, Captain-Major Luis de Magalhães had to lift the trade ban.

In 1641, the Conselho Ultramarino replaced de Magalhães with Gonçalo de Gamboa de Ayala. He had some success winning over local leaders. He also stopped Spanish ships at Cacheu. But in Bissau, two Spanish ships entered and were fully protected by the King of Bissau. Ayala threatened violence, but nothing happened. He did successfully move the Afro-European community of Geba to Farim, northeast of Cacheu.

The Portuguese could never fully control local and Afro-European traders. The economic interests of local leaders and Afro-European merchants never fully matched Portugal's. During this time, the Mali Empire's power in the region was fading. The farim of Kaabu, the king of Kassa, and other local rulers began to claim their independence.

In the early 1700s, the Portuguese left Bissau. They retreated to Cacheu after their captain-major was captured and killed. They did not return until the 1750s. Meanwhile, the Cacheu and Cape Verde Company closed in 1706. For a short time in the 1790s, the British tried to settle on Bolama.

The Slave Trade

Guinea-Bissau was one of the first areas involved in the Atlantic slave trade. While it did not send as many enslaved people as other regions, the impact was still big. At first, enslaved people were mainly sent to Cape Verde and the Iberian Peninsula. Fewer went to Madeira and the Canary Islands. In Cape Verde, they were key to developing the plantation economy. They grew indigo and cotton. They also wove panos cloth, which became a common currency in West Africa.

From 1580 to 1640, many enslaved people from Guinea-Bissau went to the Spanish West Indies. About 3,000 were shipped every year from Guinala alone. The 1600s and 1700s saw thousands of people taken from the region each year. Portuguese, French, and British companies did this. The Fula jihads and wars between the Imamate of Futa Jallon and Kaabu provided many of these captives.

People were enslaved in four main ways:

- As punishment for breaking laws.

- Selling themselves or relatives during famines.

- Kidnapped by local raiders or European raiders.

- As prisoners of war.

Most enslaved people were bought by Europeans from local rulers or traders. Every ethnic group in the region took part in the trade, except for the Balantas and Jolas. Most wars were fought just to capture people to sell to Europeans. In return, they received imported goods. These wars were more like man-hunts than fights over land or power.

Nobles and kings benefited from this trade. Common people suffered from the raids and insecurity. If a noble was captured, they were often released. Their captors would usually accept a ransom for their freedom. Kings and European traders worked together. They often made deals on how the trade would happen. They decided who would be enslaved and who would not, and the prices of enslaved people. Old writers like Fernão Guerreiro and Mateo de Anguiano asked kings about their role in the slave trade. The kings said they knew the trade was wrong. But they took part because Europeans would not buy other goods from them.

In the late 1700s, European countries slowly started to stop the slave trade. The British navy and, to a lesser extent, the U.S. Navy tried to stop slave ships off the coast of Guinea in the early 1800s. But this reduction in supply only made prices higher. It also increased illegal slave trading. Portugal ended slavery in 1869, and Brazil in 1888. But a system of contract labor replaced it. This system was only slightly better for the workers.

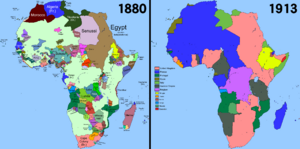

Colonial Rule

Until the late 1800s, Portugal's control of its 'colony' outside its forts was not real. African rulers held power in the countryside. Frequent attacks and killings against the Portuguese happened in the mid-1800s. Guinea-Bissau became a place of increased European colonial competition starting in the 1860s.

A dispute over the status of Bolama was settled in Portugal's favor. U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant helped resolve it in 1870. But French expansion into Portuguese claims continued. In 1886, the Casamance region, now part of Senegal, was given to France.

To improve finances and strengthen control, António José Enes reformed tax laws in 1891. He was the Minister of Marine and Colonies. He gave concessions in Guinea, mostly to foreign companies, to increase exports. The small increase in government income did not cover the cost of troops used to collect taxes. Resistance continued throughout the area. But these reforms set the stage for future military expansion.

To meet the Berlin Congress rule of 'effective occupation', the Portuguese colonial government started 'pacification campaigns'. These were mostly military failures until Capt. João Teixeira Pinto arrived in 1912. He had a large army of hired soldiers led by Senegalese fugitive Abdul Injai. He quickly and harshly crushed local resistance on the mainland. Three more bloody campaigns in 1917, 1925, and 1936 were needed to 'pacify' the Bissagos Islands.

Portuguese Guinea remained a neglected area. Administration costs were higher than income. In 1951, Portugal changed the name of all its colonies, including Portuguese Guinea. They became 'overseas provinces' (Províncias Ultramarines). This was in response to criticism from the United Nations.

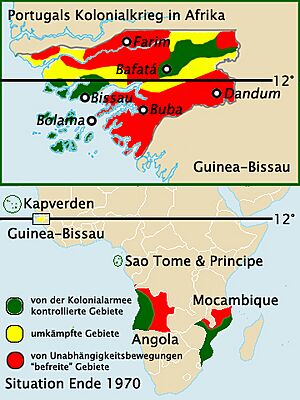

Fight for Independence

The African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC) was founded in 1956. It was led by Amílcar Cabral. At first, the party wanted peaceful methods. But the 1959 Pidjiguiti massacre pushed them towards military tactics. They focused on organizing farmers in the countryside.

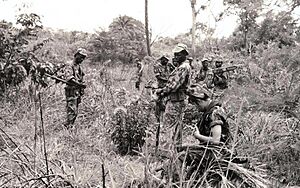

After years of planning from their base in Conakry, the PAIGC started the Guinea-Bissau War of Independence on January 23, 1963. Unlike other guerrilla groups in Portuguese colonies, the PAIGC quickly took control of large parts of the territory. The jungle-like land helped them. They had easy access to borders with friendly neighbors. They also got many weapons from Cuba, China, the Soviet Union, and left-leaning African countries. Cuba also sent artillery experts, doctors, and technicians. The PAIGC even got strong anti-aircraft weapons to defend against air attacks. By 1973, the PAIGC controlled many parts of Guinea. However, the movement faced a setback in January 1973. Its founder and leader, Amilcar Cabral, was killed.

After Cabral's death, Aristides Pereira became the party leader. He later became the first president of Republic of Cape Verde. The PAIGC National Assembly met at Boe in the southeast. They declared Guinea-Bissau's independence on September 24, 1973. The UN General Assembly recognized this in November with a 93–7 vote.

Independence and Democracy

After Portugal's Carnation Revolution in April 1974, it granted independence to Guinea-Bissau on September 10, 1974. Luís Cabral, Amílcar Cabral's half-brother, became President. The United States recognized Guinea-Bissau's independence on the same day.

In late 1980, the government was overthrown. This was a coup led by Prime Minister João Bernardo Vieira, who was also a former military commander.

Return to Democracy

In 1994, 20 years after independence, the country held its first multiparty elections for lawmakers and president. An army uprising started the Guinea-Bissau Civil War in 1998. This caused hundreds of thousands of people to leave their homes. The president was removed by a military group on May 7, 1999.

An interim government handed over power in February 2000. Opposition leader Kumba Ialá became president after two rounds of fair elections. Guinea-Bissau's return to democracy has been difficult. The economy was badly damaged by civil war. Also, the military often interfered in the government.

Kumba Ialá's Presidency

Reports said that many weapons arrived before the election. There were also some "disturbances during campaigning." These included attacks on the presidential palace and Interior Ministry by unknown gunmen. However, European monitors called the election "calm and organized."

In January 2000, the second round of a general election took place. Opposition leader Kumba Ialá of the Party for Social Renewal (PRS) won the presidential election. He defeated Malam Bacai Sanhá of the ruling PAIGC. The PRS also won the National People's Assembly election. They got 38 out of 102 seats.

2003 Coup

In September 2003, a military coup happened. It was led by General Veríssimo Correia Seabra, the Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces. President Kumba Ialá and Prime Minister Mário Pires were placed under house arrest. After several delays, elections for lawmakers were held in March 2004. A mutiny (rebellion) by military groups in October 2004 led to General Correia Seabra's death. This caused widespread unrest.

João Bernardo Vieira's Second Presidency

In June 2005, presidential elections were held for the first time since the 2003 coup. Former President Ialá returned as the candidate for the PRS. He claimed to be the country's rightful president. Former president João Bernardo Vieira, who was removed in the 1999 coup, won the election. Vieira defeated Malam Bacai Sanhá in a run-off election. Sanhá first refused to accept the results. He claimed that cheating and fraud happened in two areas, including the capital, Bissau.

Despite reports of weapons entering the country before the election, and some "disturbances during campaigning," foreign election monitors described the 2005 election as "calm and organized."

Three years later, the PAIGC won a large majority in parliament. They got 67 out of 100 seats in the parliamentary election in November 2008. In November 2008, President Vieira's home was attacked by armed forces members. A guard was killed, but the president was unharmed.

On March 2, 2009, Vieira was killed. Early reports said a group of soldiers did it. They were getting revenge for the death of General Batista Tagme Na Wai. He was the head of joint chiefs of staff. He had been killed in an explosion the day before. Vieira's death did not cause widespread violence. But there were signs of trouble in the country. Military leaders promised to follow the constitution for succession. National Assembly Speaker Raimundo Pereira was appointed as an interim president. A nationwide election was held on June 28, 2009. Malam Bacai Sanhá of the PAIGC won. He defeated Kumba Ialá of the PRS.

2012 Coup

On January 9, 2012, President Sanhá died from complications of diabetes. Pereira was again appointed as an interim president. On the evening of April 12, 2012, members of the country's military staged a coup d'état. They arrested Pereira and a leading presidential candidate. Former vice chief of staff, General Mamadu Ture Kuruma, took control of the country during the transition. He started talks with opposition parties.

Presidencies of José Mário Vaz and Umaro Sissoco Embaló

José Mário Vaz was the President of Guinea-Bissau from 2014 until the 2019 presidential elections. At the end of his term, Vaz became the first elected president to finish his five-year term. He lost the 2019 election to Umaro Sissoco Embaló. Embaló took office in February 2020. He is the first president elected without the support of the PAIGC.

In February 2022, there was a failed coup attempt against President Embaló. Another coup attempt in 2023 led to fights between government forces and the National Guard.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Guinea-Bisáu para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Guinea-Bisáu para niños

- Politics of Guinea-Bissau

- United Nations Peacebuilding Support Office in Guinea-Bissau (UNOGBIS)

- City of Bissau history and timeline

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |