Regency of Algiers facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Regency of Algiers

دولة الجزائر (Arabic)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1516–1830 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

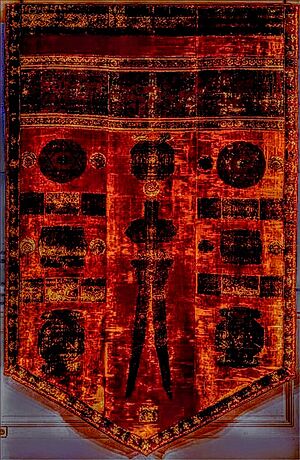

Motto: دار الجهاد

Bulwark of the Holy War

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

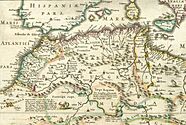

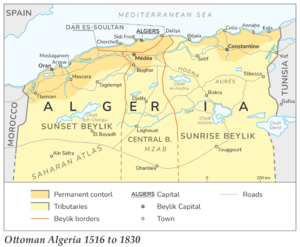

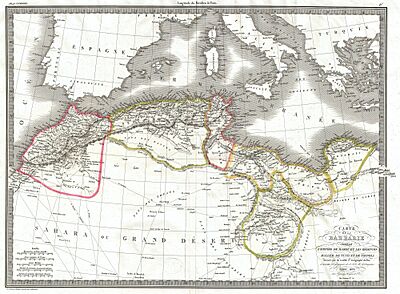

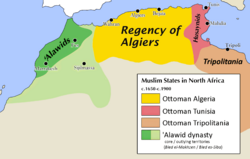

Overall territorial extent of the Regency of Algiers in the late 17th to 19th centuries

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Autonomous eyalet (Client state) of the Ottoman Empire De facto independent since mid-17th century |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Algiers | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | Ottoman Turkish and Arabic (since 1671) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Algerian Arabic Berber Sabir (used in trade) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Official, and majority: Sunni Islam (Maliki and Hanafi) Minorities: Ibadi Islam Shia Islam Judaism Christianity |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Algerian or Algerine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | 1516–1519: Sultanate 1519–1659: Regency 1659–1830: Stratocracy (Political status) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pasha | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1516–1518

|

Aruj Barbarossa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1710–1718

|

Baba Ali Chaouch | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

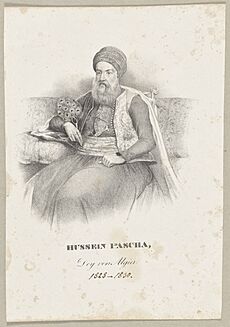

• 1818–1830

|

Hussein Dey | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1509 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1516 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1521–1791 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1541 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Algerian-Sherifian conflicts

|

1550–1795 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1580–1640 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Turkish abductions

|

1627 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Janissary Revolution

|

1659 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1681–1688 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Maghrebi war

|

1699–1702 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Spanish–Algerian war

|

1775–1785 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1785–1816 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Invasion of Algiers

|

1830 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1830

|

3,000,000–5,000,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Major coins: mahboub (sultani) budju aspre Minor coins: saïme pataque-chique |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Algeria | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Regency of Algiers (Arabic: دولة الجزائر, romanized: Dawlat al-Jaza'ir) was a powerful state in North Africa from 1516 to 1830. It was part of the Ottoman Empire, but it mostly ruled itself. This state was famous for its strong navy and for its "corsairs," who were like private ships that captured other ships.

The Regency was started by two brothers, Aruj Barbarossa and Hayreddin Barbarossa. They made Algiers a very strong base. From here, their corsairs would sail out to capture merchant ships from European countries. They would take the goods and sometimes the people on board.

In the 1600s, the Regency became even more independent from the Ottoman Empire. Its leaders were chosen by a special council, not by the Ottoman Sultan. This made Algiers a unique military republic.

Over time, Algiers had many conflicts with European countries like France and Spain. These wars were often about trade and control of the Mediterranean Sea. The American Revolution also changed things. American ships were no longer protected by British payments to Algiers. This led to conflicts known as the Barbary Wars in the early 1800s.

By the 19th century, Algiers faced many problems. There were political fights, bad harvests, and less money from capturing ships. This made the state weaker. France took advantage of this in 1830 and invaded Algiers. This led to French rule until 1962.

Contents

- History

- Government and Society

- Economy

- Society

- Culture

- Legacy

- Images for kids

- See also

History

How Algiers Started

The Barbarossa Brothers

After Spain finished its wars in 1492, it took control of several ports in North Africa. These ports were important for trade routes that brought gold and other goods. The people in these areas asked for help against the Spanish.

Two famous Ottoman corsair brothers, Aruj Barbarossa and Hayreddin Barbarossa, came to help. They were skilled sailors and fighters. In 1516, they successfully captured the city of Algiers. Aruj continued to conquer more areas in central Algeria. However, he was killed in 1518.

His brother, Hayreddin, then became the leader. He realized he needed more support to keep Algiers safe from Spanish attacks. So, in 1519, he asked the Ottoman Sultan to make Algiers part of the Ottoman Empire. The Sultan agreed and sent him soldiers. Hayreddin became the "Prince of Princes" (Beylerbey) of Algiers.

Hayreddin, with help from local groups, took Algiers again in 1525. In 1529, he destroyed a Spanish fort that was threatening the port. He used the fort's stones to build the port of Algiers. This port became the main base for the Algerian corsair fleet. He also helped over 70,000 refugees from Spain settle in Algeria. They helped the culture of the Regency grow.

Growing the Regency

Under Hayreddin's next leader, Hasan Agha, Algiers fought off a big naval attack by Emperor Charles V in 1541. The Algerians won, taking many ships and cannons from the enemy. This victory helped Algiers become stronger and expand its lands.

Hayreddin's son, Hasan Pasha, and another leader, Salah Rais, continued to expand the territory. They conquered new cities and fought against Morocco, which was allied with Spain. They even reached Fez in 1554. Another leader, Uluç Ali Pasha, captured Tunis from the Spanish in 1574. His corsair ships also helped the Ottoman fleet in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571.

Algerian corsairs became very powerful under Hassan Veneziano Pasha. They sailed all over the Mediterranean Sea, even reaching the Canary Islands. Their power was so great that the waters from Spain to Sicily were not safe for other ships.

The Golden Age of Algiers (1600s)

Becoming Independent

The early 1600s was a "Golden Age" for the corsairs. Algerian ships started using new types of sailing ships. This meant they needed fewer rowers, who were often captured people. Many people who had been forced out of Spain joined the corsairs. They helped weaken Spain by raiding its coasts.

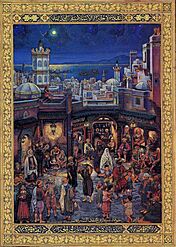

Algerian corsairs traveled far, even reaching Iceland in 1627 and Ireland in 1631. Algiers became a busy market where captured goods and people were bought and sold. This made Algiers a very rich city with over 100,000 people.

During this time, Algiers also became more independent from the Ottoman Empire. France had special trading rights in Algiers, which Algerians didn't like. When France tried to expand these rights, the Algerians destroyed their trading post. This showed that Algiers had its own ideas about foreign relations.

Corsairs started attacking ships even if their countries were at peace with the Ottoman Sultan. Many European people who converted to Islam became important corsair captains. They focused on what was best for Algiers, not necessarily for the Ottoman Empire.

Dealing with Other Countries

Because Algiers was becoming so independent, European countries started making treaties directly with Algiers. These treaties were about trade, payments, and freeing captured people. Algiers used its corsairs as a tool in its foreign policy. It would capture merchant ships to make European countries sign peace treaties and pay for safe passage.

This made the rulers of Algiers seem like "champions" to their people. It also gave them power on the international stage, even though some Europeans still called them a "nest of Pirates." A Dutch expert named Hugo Grotius even said that Algiers acted like a "sovereign power" (an independent state).

Algiers signed treaties with France, England, and the Dutch Republic. These treaties often involved payments or weapon supplies. But there were still many conflicts. France, under Louis XIV, built a strong navy to fight the corsairs. They bombed Algiers several times between 1682 and 1688. Eventually, a 100-year peace treaty was signed.

Algiers as a Regional Power (1700s)

Wars with Neighbors

In the 1700s, Algiers had peaceful relations with Europe. This meant less money from corsair activities. So, Algiers looked to its neighbors in North Africa, Tunis and Morocco, for new income. Algiers saw Tunis as a dependent state. It invaded Tunis in 1694 and put its own ruler in charge.

Tunis fought back, allying with Morocco in 1700. But Algiers won these wars. Tunis remained under Algerian influence until the early 1800s. Morocco also tried to invade Algerian territory several times, but failed. The Moulouya River became the border between Algeria and Morocco.

The Dey-Pashas

The Algerian leader, called the Dey, wanted to remove the Spanish from Oran. In 1707, Algerian forces took the city. But Spain recaptured it in 1732.

In 1710, Dey Baba Ali Chaouch took the title of Pasha for himself. This ended the Ottoman Sultan's direct influence over Algiers. Even when the Ottoman Empire signed a peace treaty with Austria in 1718, Dey Ali Chaouch still allowed Algerian ships to capture Austrian vessels. This showed that Algiers had its own foreign policy.

In 1748, a "Fundamental Pact" was created. It set out the rights of the people and rules for the army. This helped stabilize the government.

Muhammad ben Othman Pasha became Dey in 1766. He ruled for 25 years and made Algiers prosperous. He built new defenses and improved the water supply. He also made the navy stronger and developed trade. He made sure the different parts of the Regency were peaceful.

The Dey also played a role in international affairs. He made European countries like Britain, Sweden, and Denmark pay more money each year. Denmark even sent a naval force against Algiers in 1770, but it failed.

In 1775, Spain launched a big attack on Algiers to stop corsair activity. It was a huge failure for Spain. Algiers also defeated Spanish attacks in 1783 and 1784. In 1791, Algiers finally retook Oran from Spain. This ended nearly 300 years of conflict between Algeria and Spain.

The End of the Regency (1800s)

Internal Problems

At the start of the 1800s, Algiers faced many problems. There was political unrest and money troubles. A crisis caused by bad harvests led to violence and instability. Rebellions broke out, especially in the east and west. Morocco took advantage of this and captured some Algerian territories. Tunis also broke free from Algerian rule.

The Barbary Wars

Because of its money problems, Algiers started capturing American and European ships again. In 1785, Algerian ships attacked American merchant ships. The U.S. president, George Washington, agreed to pay a large sum of money and an annual payment to Algiers for safe passage.

However, the United States defeated Algiers in the Second Barbary War in 1815. This ended the threat to U.S. shipping in the Mediterranean. European countries also decided they would no longer tolerate Algerian raids. In 1816, British and Dutch navies bombed Algiers. This weakened the Algerian navy and led to the freeing of many captives.

French Invasion

During the time of Napoleon, Algiers made a lot of money from trade with France. France bought a lot of food from Algiers on credit. In 1827, the last Dey of Algiers, Hussein Dey, demanded that France pay back a 31-year-old debt.

The French consul's response angered Hussein Dey. He hit the consul with a fly whisk and insulted him. The French King, Charles X, used this incident as an excuse to invade Algeria. On June 14, 1830, France launched a full-scale invasion. Algiers surrendered on July 5, and Hussein Dey went into exile. This marked the end of the Regency of Algiers.

Government and Society

How Algiers Was Governed

The Regency of Algiers was a unique state. It was a strong base for the Ottoman Empire in North Africa. It had a very powerful army of soldiers called janissaries. Like the island of Malta, which was a base for Christian corsairs, Algiers was home to Muslim corsairs.

A Spanish captive in Algiers in the late 1500s wrote that Aruj Barbarossa "effectively began the powerful greatness of Algiers." Over time, Algiers became more self-governing, even though it still recognized the Ottoman Sultan.

The Start of the State (1516)

Aruj Barbarossa wanted to build a strong Muslim state in central North Africa. He got support from religious leaders. He imagined a government like a military republic.

The military, made up of Turks and European converts, had a lot of power. Local Algerians were not allowed to hold high government jobs.

Hayreddin's Strong Rule

Hayreddin Barbarossa became the new leader. He was a smart leader and a great captain. He decided to join the Ottoman Empire to get support against Spain. The Sultan recognized him as a "pasha" and "beylerbey" (a high-ranking governor).

To run the country, Hayreddin relied on a council of janissaries. These leaders saw themselves as Algerians. Hayreddin also organized the corsairs into a strong group. This group became a model for other corsair states in Tunis and Tripoli. The Barbarossa brothers also built up the city of Algiers as their new capital.

Ottoman Rule (1519–1659)

Beylerbeylik Period (1519–1587)

In its early years, Algiers' foreign policy was closely linked to the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman Sultan appointed the rulers, called beylerbeys. These beylerbeys often stayed in power for many years and controlled Tunis and Tripoli as well. Algiers became the most successful port in North Africa and a very diverse city. Europeans called it a "scourge of Christendom" and a "rogue state."

The beylerbeys acted almost like independent rulers, even though they recognized the Sultan. They sent yearly payments to Constantinople. In return, Constantinople sent more janissaries. However, Algiers and Constantinople sometimes disagreed, especially about corsair activities, which the Sultan couldn't control.

Pashalik Period (1587–1659)

The Ottoman Empire became worried about Algiers' growing independence. So, in 1587, they changed the system. They divided North Africa into three separate regions: Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli. This period was known for political instability because the governors were replaced every three years. However, it was also the "Golden Age of Algiers" because of its huge corsair fleet.

The janissary army in Algiers became stronger and more independent. By 1626, their military council, called the diwân, was the real power in Algiers, not the pashas. This allowed Algiers to make its own treaties with countries like the Dutch Republic and France. The pasha's role became less important.

The corsair captains also formed their own council. They focused on corsair operations, which became the main way Algiers dealt with European countries. They ignored the Ottoman leaders and used capturing ships and people to keep Algiers financially and politically independent.

A Self-Governing Military Republic (1659–1830)

Janissary Revolution (1659)

The janissaries in Algiers were unhappy with the Ottoman pashas. They felt the pashas were corrupt and not good at managing the state. In 1659, a pasha kept money meant for the corsairs. This caused a huge revolt.

Khalil Agha, the janissary commander, took power. He accused the pashas of corruption. The janissaries took away the pasha's power, making his role just ceremonial. They gave executive power to Khalil Agha, but his rule was limited to two months. The legislative power went to the diwân council. The Ottoman Sultan had to accept this new government. This marked the beginning of the Aghas' rule, and Algiers became a military republic.

The Deylik Period (1671–1830)

In 1671, the corsairs killed Agha Ali. The previous three janissary leaders had also been killed. The janissaries and corsairs decided to appoint an old Dutch corsair captain named Hadj Mohammed Trik as their leader.

They gave him the titles of Dey (meaning "maternal uncle"), Doulateli (head of state), and Hakem (military ruler). After 1671, the Deys became the true leaders of Algiers. Their power was limited by the diwân council. This formal recognition from European states made Algiers truly independent from the Ottoman Empire.

The pashas sent from Constantinople tried to cause trouble to regain power. But from 1710 onwards, the Deys took the title of Pasha themselves. They no longer accepted representatives from the Ottoman Sultan. They also gained more control over the janissaries and corsairs.

The corsairs didn't like treaties that limited their activities, which were their main source of income. They rebelled and killed Dey Mohamed Ben Hassan in 1724. But the new Dey, Baba Abdi, quickly brought order back. He stabilized the Regency and fought corruption. The diwân council became less powerful, and the Dey's cabinet gained more control. This led to more stability.

Relations with Constantinople became more formal. The Sultan was assured of Algiers' "obedience" in exchange for recruiting soldiers from Ottoman lands. But the Dey was not bound by Ottoman foreign policy.

The Deys also gained more control over the three provinces (beyliks) of Algiers. In 1817, Dey Ali Khodja moved the seat of power from the old palace to the Casbah citadel. This showed his strong control over the janissaries.

Some historians believe that Algiers was moving towards becoming a modern nation-state before the French invasion.

Administration

The government of Ottoman Algeria used a mix of Ottoman systems and local traditions. The corsairs used their military power to fight against Christian states. They also used their strength to control local groups and create a foreign ruling class. The government respected local religious leaders and protected the people from Christian powers.

Algiers' Military Government

Some people at the time described the Regency of Algiers as a "despotic, military-aristocratic republic." This means that the military held all the power: executive, legislative, and judicial. One writer compared it to the Roman Empire.

Montesquieu thought Algiers had an aristocracy with some republican and equal features. He noted that they could choose and remove their ruler. Historian Edward Gibbon called it a "military government that floats between absolute monarchy and wild democracy." It was unusual for a Muslim country to have elected rulers and some democracy.

The Dey of Algiers

The Dey of Algiers was the head of state. He was chosen by election, but his power was very strong. He was in charge of enforcing laws, keeping internal peace, collecting money, and paying the soldiers. However, his power was still limited by the corsair captains and the janissary council. Anyone from these groups could become Dey.

The Dey's money came from his official salary and gifts. But if he was killed, his wealth went back to the public treasury. This meant that Deys were rich but not always in full control of their money.

The Dey was chosen by a unanimous vote among the armed forces. The Ottoman Sultan would then send a formal approval. The Dey was elected for life and could only be replaced if he died. This often led to violence and instability, as overthrowing the current leader was the only way to gain power.

The Dey's Cabinet

The Dey appointed five ministers to help him govern Algiers. These ministers formed the "Council of the Powers":

- Khaznaji: The treasurer, in charge of money and the public treasury. He was like the chief secretary of state.

- Agha al-mahalla: The commander-in-chief of the janissaries and minister of internal affairs. He also governed the Algiers region.

- Wakil al-Kharaj: The minister of the navy and foreign affairs. He was the head of the corsair captains and managed weapons and forts.

- Khodjet al-khil: In charge of relations with local tribes, taxes, and leading expeditions into the countryside. He was also the "secretary of horses."

- Bait al-Maldji: Managed state property, including vacant inheritances and confiscated goods.

The Dey also chose religious judges, called muftis, who were the highest legal authorities.

The Diwân Council

The diwân of Algiers was a very important council. It was first led by a janissary Agha. Over time, it became the main administrative body of the country. By the mid-1600s, the diwân held the real power and even elected the head of state.

The diwân had two parts:

- The private (janissary) diwân: This was made up of senior janissary officers. They voted on important policies. The commander-in-chief was elected for two months as president of this diwân.

- The public, or Grand Diwân: This was a larger council with 800 to 1500 scholars, preachers, corsair captains, and local leaders. The Dey would consult this council on important decisions. However, by the 1800s, the Dey could sometimes ignore the diwân if he felt powerful enough.

Managing the Territory

The Regency was divided into different regions called beyliks, each ruled by a bey (a local governor).

- Dar Es-Soltane: This included the city of Algiers and nearby ports.

- The beylik of Constantine: In the east, with its capital in Constantine.

- The beylik of Titteri: In the center, with its capital at Médéa.

- The beylik of the West: Started in 1563, with its capital at Mascara, then Mazouna, and later Oran.

These beyliks had a lot of freedom. The Ottoman government in Algiers relied on local Arab tribes to help with administration. The beys divided their regions into smaller areas, each governed by a commander who kept order and collected taxes. These tribes had special benefits, like not having to pay taxes, in return for their help.

Economy

The Ransom Economy

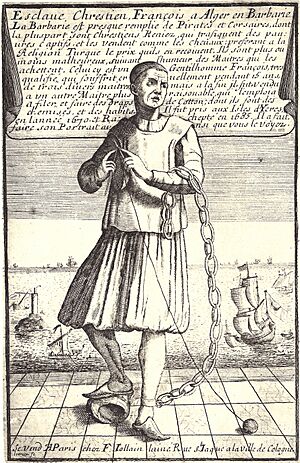

Algerian corsairs captured many people from ships and coastal areas. These captives were brought to the slave market in Algiers. Between 25,000 and 36,000 captives of many different backgrounds passed through this market. Over a million Europeans were captured in total during this period. This trade was a very important part of Algiers' economy.

After being checked, captives were put into three groups:

- Those who could be ransomed: These were usually wealthy people. Their owners would treat them well to keep their value high, hoping to get a good ransom quickly.

- Those who could not be ransomed: These were poorer people. They often became rowers on ships or were forced to do hard labor. Some became household servants.

- Those who were freed without ransom: This happened if they were exchanged for Muslim captives, or if there were agreements between states, or after wars.

Government-owned captives lived in prisons called "bagnos." There were six main prisons in Algiers. Privately owned captives lived in houses or larger prisons funded by their owners.

In Europe, money for ransoms came from the captive's family, state donations, or religious groups. These groups would negotiate in Algiers to free the captives. Captives who could buy their own freedom were allowed to move freely in Algiers.

In the 16th century, captives were exchanged for small amounts. But in the 17th century, ransoms became much higher. For example, the governor of the Canary Islands bought his freedom for 60,000 pounds in 1670.

After a ransom was paid, there was an extra fee for customs duties, which was over 50% of the agreed ransom. This money was divided among customs, the pasha or dey, the secretary of state, the harbor master, and the prison guards.

Captives who were skilled carpenters and built or repaired ships could not be ransomed at any price.

Payments and Gifts

Algiers made European trading partners pay fees for safe travel in the western Mediterranean. These payments were made yearly or every two years. The amount depended on the relationship between the country and Algiers. For example, the United States paid $1 million annually in 1795.

Taxes

The Regency collected taxes. Some taxes followed Islamic law, like the cushr (a tenth of agricultural products). But some taxes were more like forced payments. Nomadic tribes in the mountains paid a fixed tax based on their wealth. Rural people also paid a tax to support the Muslim armies. City dwellers paid market taxes and fees to artisan groups.

Local governors (beys) also collected gifts, called dannush, every six months for the Deys and their ministers. The bey of the western province was expected to pay over 20,000 doro in cash, plus jewelry, horses, slaves, and goods like wool and honey. The gifts from the eastern province were even larger.

Farming

Farming was very important to the Regency's economy, sometimes even more than corsair activities. Farmers used techniques like leaving fields unplanted for a season and rotating crops. The main crops were wheat, cotton, rice, tobacco, watermelon, and corn. Grains and livestock products were a big part of the export trade.

The state and wealthy city people owned very fertile lands near towns. These lands were farmed by tenants who received a fifth of the harvest. The Metija region produced many fruits and vegetables. Grapes were also grown, and Algerian wine was popular in Europe.

Tribes owned large areas of land where they mostly grew wheat and barley. Most people in the western and Sahara regions were pastoralists. They raised sheep, goats, and camels, and grew dates. Their products like butter, wool, and skins were traded to the north.

Manufacturing and Crafts

Manufacturing was not highly developed, except for shipyards. These yards built large ships from oak wood. Smaller ports built smaller boats for fishing and transporting goods. Workshops supported repairs and rope-making. Quarries provided stone for buildings and forts. Foundries produced cannons for the navy and forts.

Craftsmanship was rich and widespread. Cities were centers for crafts and trade. City people were mostly artisans and merchants. Common crafts included weaving, woodturning, dyeing, and tool making. Tlemcen had over 500 looms.

Trade

Internal trade was very important. Products like wool from the countryside were traded in cities. Foreign trade mostly happened by sea, especially with Marseille. There was also overland trade with Tunisia and Morocco. Trade routes were kept safe by military posts and local tribes. Travelers could rest at special inns called caravanserai.

Algiers had important economic ties to the Sahara Desert. Algiers and other cities were major destinations for the trans-Saharan slave trade.

Society

People in Algeria felt connected to their tribes, but also to their country. Many old texts speak of "our homeland" (watan al jazâ'ir). This shows a sense of national identity. Society was divided into two main groups:

- State or Khassa: This group included Ottoman officials, Arab tribes, and Berber highlanders.

- Society or Ra'iya: This group included different religious, tribal, and city communities.

City Life

About 10,000 Turks formed the ruling class. They were officials, politicians, and soldiers. There were no harems in Algiers because rulers were elected, not hereditary. A new group called kouloughlis emerged. These were children of Turkish soldiers and Algerian women. There were also native Algerians, Black people, immigrants from Spain, and a Jewish minority.

Muslim faith was very important in daily life. Guilds (groups of artisans) and city neighborhoods helped meet people's needs and created a sense of community. Public business was done in both Arabic and Ottoman Turkish.

Wealthy people in coastal cities owned the best homes and land. City dwellers had access to springs, fountains, bath houses, shops, and coffeehouses. These were places where friends could chat over mint tea.

City society had a friendly, family-like feel. There wasn't much class rivalry between the rich merchants and the poorer shopkeepers and craftsmen.

Social Structures

In North Africa before colonial times, the tribe was a main social and political group. Tribes often competed for land and water. But they also had a sense of unity based on family ties and shared Islamic faith. This helped prevent major conflicts and allowed them to unite against outside threats.

This system continued under the Regency. Cities and villages had their own organizations within the tribal systems. Cities, made up of families, allowed for more individual freedom. However, tribes still adapted to city life and remained important in some regions.

A complex relationship developed between tribes and the state. Tribes helped the government by protecting cities, collecting taxes, and providing military control in the countryside. In return, they gained legitimacy from their connection to the government. Tribes that paid taxes were called rayas. Tribes that resisted taxes were called siba. But even siba tribes depended on markets organized by the state.

Tribal Leaders

The political power of tribes often came from their military strength or their religious background. There were three types of tribal leaders:

- Djouads: These were warriors who led powerful tribes or groups of tribes. They often remained independent. The Regency sometimes saw these tribes as allies.

- Sharifs: These were religious nobles who claimed to be descendants of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Some were part of Sufi religious groups.

- Marabouts: These leaders, like the Awled Sidi Cheikh, ruled western oases until the 1800s. They were like local princes, not a central power, but they were loyal to Algiers. They also shared in the money from corsair activities.

Culture

Education

Education in Algiers mostly happened in small primary schools called kuttabs. These schools taught basic reading, writing, and religion, especially in rural areas. Local religious leaders and elders did most of the teaching.

Higher education took place in madrasas (universities) in larger cities. Teachers often held legal positions as judges. These schools were funded by donations and the government. Students learned about Islamic law and medieval Islamic medicine. After finishing, they could become teachers, judges, or continue their studies in Tunis, Fez, or Cairo.

Initially, western Algeria, especially Tlemcen, was a major learning center. But its schools declined due to neglect. The military leaders were more interested in building forts and navies. This changed when Mohammed el Kebir, the bey of Oran, invested in renovating and building new schools.

Architecture

Architecture in Algiers showed a mix of different styles and local ideas. Mosques started to have domes, influenced by Ottoman design. But their minarets (towers) usually stayed square, following local tradition. The oldest mosque still standing in Algiers was built in 1622. The New Mosque, built in 1660–1661, is a great example of Ottoman, North African, and European design. By the late 1700s, Algiers had over 120 mosques.

Ottoman influence also brought new types of decorative tiles. These tiles, called zellij, had geometric patterns and were used on walls and floors. They came from Turkey, Tunisia, Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands.

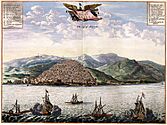

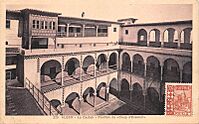

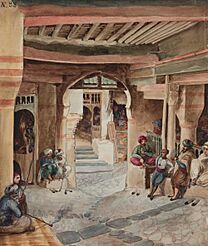

Algiers was protected by a wall about 3.1 kilometers (1.9 miles) long with five gates. There were also forts outside the city, like the "star fort" and the "Emperor fort." The highest point of the city had a citadel called the qasba. The lower town near the harbor was the center of government and had markets, mosques, palaces, and barracks.

The Djenina Palace, built in the mid-1500s, was the seat of power. One Spanish captive described it as "well built after the modern way of Architecture." It had beautiful galleries with marble columns. In 1817, the Dey moved the seat of power to the Casbah citadel.

Arts

Crafts

Ottoman influence shaped many Algerian crafts:

- Brassware: Many copper lanterns, trays, and ewers were made in Algiers, Constantine, and Tlemcen. They often had Ottoman designs like tulips.

- Door Knockers: Fancy bronze door knockers were made in Tlemcen.

- Saddles: Saddlers made velvet saddles embroidered with gold or silver, along with belts and boots with Ottoman decorations.

- Rugs: Rugs from the Guergour region and by certain tribes showed patterns with large central diamond shapes.

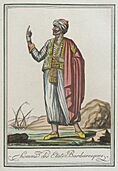

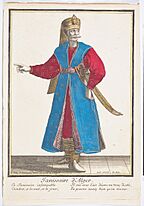

- Clothing: The clothing of leaders was known as "Algerian style." This included turbans, red hats, cloaks, embroidered vests, baggy trousers, and slippers. They often carried curved swords.

- Lace and Embroidery: Fine needle lace and embroidery were made in Algiers and other cities.

- Jewelry: Gold and silversmiths made jewelry like coronet-like headpieces, earrings, bracelets, and necklaces.

Music

New arrivals from Turkey and Spain brought different music styles. Ottoman military music, called "mehter," was played by janissary bands. Andalusian music, brought by people from Spain, developed into three styles: gharnati in Tlemcen, ma'luf in Constantine, and sana' in Algiers. This music was popular in coffeehouses and played by orchestras.

Today, Algerian musician El-Hachemi Guerouabi sings about the corsairs in his song "Corsani Ghanem," based on 16th-century Algerian Arabic poetry.

Legacy

Europeans often saw Algiers as a place of piracy and disorder. One historian in the 1800s said it was a "nation living from privateering" that made many European countries pay tribute. However, some modern historians say this is a "colonial myth." They point out that after the 1600s, money from corsair activities became less important.

In the 1700s, the main income for the Regency came from tribute payments, trade, customs, and farming. Historians say that the Ottomans in North Africa helped create an Algerian political entity with its own government and a good standard of living.

Historians also note that the Ottoman period was important for the development of modern Algeria. While Algeria wasn't a "nation" in the modern sense, it was a state with its own unique identity. It helped create a sense of community among Algerians. However, a true nation-state only fully emerged after many years of French rule and Algerian resistance, leading to the Algerian War of Independence in 1954.

Images for kids

-

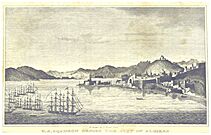

View of the city of Algiers, Robert Salmon (1828)

-

Allegory of Freedom for Ransomed Barbary Captives, in Gratitude to Jerome Bonaparte, by François-André Vincent (1746–1816)

See also

- Andalusi nubah music

- Alonso de Contreras, Spanish privateer

- Islamic geometric patterns

- Yusuf Rais pirate

- List of Ottoman rulers of Algiers

- Ottoman clothing

- Ottoman music

- Sayyida al Hurra pirate leader

- Treaty of Tripoli