History of Thailand (1932–1973) facts for kids

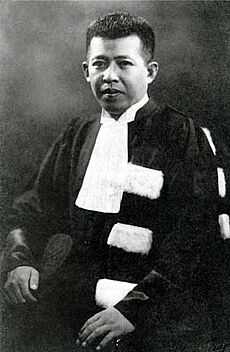

The history of Thailand from 1932 to 1973 was a time mostly led by military dictatorships. The main leaders were Phibun, a military leader who worked with Japan during World War II, and Pridi Phanomyong, a civilian politician who started Thammasat University. Pridi was briefly prime minister after the war.

After Pridi left power, other military leaders took over. These included Phibun again, Sarit Thanarat, and then Thanom Kittikachorn. During their rule, Thailand kept its old traditions but also became more modern and like Western countries, especially with help from the US. This period ended when Thanom resigned after a violent event where students from Thammasat University led protests for democracy.

From 1939, the official name of the country changed from the Kingdom of Siam to the Kingdom of Thailand. This name is still used today.

Contents

Siamese Revolution (1932–1939)

The military took power in a peaceful event called the Siamese revolution of 1932. This changed Siam's government from a country ruled by an absolute king to a constitutional monarchy. This meant the king would share power with a government.

King Prajadhipok first accepted this change. But he later gave up his throne because he disagreed with the new government. When he left, King Prajadhipok said he was happy to give power to all the people. But he did not want to give it to one person or group who would rule without listening to the people.

The new government in 1932 was led by military officers like Phraya Phahol Pholphayuhasena and Phraya Songsuradej. In December, they created Siam's first constitution. This constitution set up a national assembly or parliament. Half of its members were chosen, and half were indirectly elected. The government promised full democratic elections once more people had finished primary school. A prime minister and his team were chosen. This kept up the appearance of a constitutional government.

Once the new government was set up, different groups within it started to disagree. There were four main groups. These included older civilians, senior military officers, younger army and navy officers, and young civilians led by Pridi Phanomyong.

The first big disagreement happened in 1933. Pridi was asked to create a new economic plan. His plan suggested that the government take over large areas of farmland. It also called for quick government-led industrial development. The plan also wanted more higher education so that royal families and rich people would not be the only ones working in government. However, many in the government quickly called his plan "communist".

Because Pridi's plan affected private property, conservative members of the government were very worried. They wanted the government to reverse the changes made by the revolution. But when the prime minister tried to do this, Phibun and Phraya Phahol launched another peaceful takeover. They removed the old government. Phraya Phahol became the new prime minister. His new government did not include any royal family supporters.

Civil War

A group supporting the king fought back in late 1933. Prince Boworadej, a grandson of King Mongkut, led an armed revolt against the government. He gathered soldiers from different provinces and marched towards Bangkok. He captured the Don Muang Aerodrome. The prince said the government disrespected the king and supported communism. He demanded that the government leaders resign. He hoped that some soldiers in Bangkok would join him, but they stayed loyal to the government. The navy stayed neutral and went to its bases in the south. After heavy fighting outside Bangkok, the royalists were defeated. Prince Bovoradej then went to live in French Indochina.

One result of stopping this revolt was that the king's standing became weaker. After the revolt began, King Prajadhipok sent a message saying he was sad about the fighting. It is not clear why he did this. But his decision to stay away from the fighting was seen by the winners as a sign that he did not do his duty. By not fully supporting the government, his credibility was hurt.

A few months later in 1934, King Prajadhipok went abroad for medical treatment. His relationship with the new government had been getting worse. While abroad, he talked with the government about the conditions for him to remain a constitutional monarch. He wanted to keep some traditional royal powers. However, the government did not agree.

In his speech when he gave up the throne, Prajadhipok said the government did not care about democracy. He said they ruled like dictators and did not let the people have a real say. In 1934, a new law called the Press Act was passed. It stopped the printing of anything that could harm public order or morals. This law has been strictly used ever since.

People did not react much to the king giving up the throne. Everyone was worried about what would happen next. The government did not challenge the king's statement. This was because they feared more arguments. Those against the government stayed quiet after the royalist rebellion failed.

After defeating the royalists, the government had to keep its promises. It took stronger steps to make important changes. The currency was no longer tied to gold, which helped trade recover. Spending on education increased four times, greatly raising the number of people who could read and write. Local and provincial governments were elected. In November 1937, direct elections were held for the national assembly. However, political parties were still not allowed. Thammasat University was started by Pridi. It was a more open choice than the very selective Chulalongkorn University. Military spending also greatly increased. This showed the growing power of the military. Between 1934 and 1940, the army, navy, and air force were equipped better than ever before.

King Ananda Mahidol (Rama VIII)

After King Prajadhipok left Siam and gave up his throne, the government chose Prince Ananda Mahidol as the next king. He became King Rama VIII. At that time, he was still in school in Switzerland. For the first time, Siam did not have a king living in the country. This lasted for fifteen years. The government believed he would be easier to work with than Prajadhipok.

From Siam to Thailand (1939–1946)

Rise of Phibunsongkhram

The military, led by Major General Phibun as defense minister, and civilian liberals, led by Pridi as foreign minister, worked well together for several years. But when Phibun became prime minister in December 1938, this teamwork stopped. The military's control became much clearer. Phibun admired Benito Mussolini, a strong leader from Italy. His government soon showed signs of being like a fascist government. This meant it was very strict and controlled. In early 1939, forty political opponents were arrested. After unfair trials, eighteen were executed. These were the first political executions in Siam in over a hundred years. Many others, like Prince Damrong, were sent away from the country. Phibun also started a campaign against Chinese business people. Chinese schools and newspapers were closed, and taxes on Chinese businesses went up.

Phibun and Luang Wichitwathakan, who spoke for the government's ideas, copied how Hitler and Mussolini used propaganda. They wanted to make the leader seem like a hero. They knew the power of mass media, so they used the government's control over radio to get people to support them. Popular government slogans were always on the radio, in newspapers, and on billboards. Phibun's picture was everywhere. Pictures of the former King Prajadhipok, who spoke out against the strict government, were banned. At the same time, Phibun passed many strict laws. These laws gave the government almost unlimited power to arrest people and censor the press. During World War II, newspapers were told to print only good news from countries like Germany and Japan. Sarcastic comments about Thailand's situation were not allowed.

Fascist Thailand

On June 23, 1939, Phibun changed the country's name from Siam to Prathet Thai (Thai: ประเทศไทย). This means "land of the free." This was a nationalist act. It suggested that all people who spoke Tai languages, like the Lao and Shan, were united. But it did not include the Chinese. The government's slogan became "Thailand for the Thai."

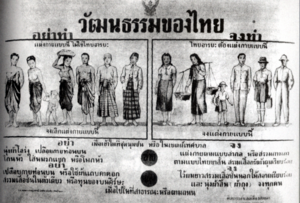

Cultural Revolution

Becoming modern was also a key idea in Phibun's new Thai nationalism. From 1939 to 1942, he issued twelve Cultural Mandates. These rules required all Thais to salute the flag, know the national anthem, and speak the national language. The mandates also encouraged Thais to work hard, stay informed, and dress in a Western style. By 1941, it became illegal to make fun of those who tried to promote national customs. The program also included fine arts. The government supported very nationalistic plays and films. These often showed a glorious past where Thai warriors bravely fought for freedom or honor. Patriotism was taught in schools and was a common theme in songs and dances.

At the same time, Phibun worked hard to remove royal influences from society. Traditional royal holidays were replaced with new national events. Royal and noble titles were no longer used. Even the Buddhist clergy was affected. The status of the royal-sponsored Thammayuth sect was lowered.

All cinemas were told to show Phibun's picture at the end of every movie, just like the king's portrait. The audience was expected to stand and bow. Another sign of Phibun's growing personality cult was seen in official decorations. He was born in the year of the cock, and this symbol started to replace the traditional wheel. Also, Phibun's lucky birth color, green, was used in official decorations.

Franco-Thai War

In 1940, most of France was taken over by Nazi Germany. Phibun quickly wanted to get back lands that France had taken from Siam in 1893 and 1904. At that time, the French had used force to change the borders of Siam with Laos and Cambodia. They made Thailand sign unfair agreements. To get these lands back, the Thai government needed help from Japan against France. This help was secured through a treaty between Thailand and Japan in June 1940. Also in 1940, Britain and Thailand signed a non-aggression pact. Britain accepted Japan's demands to close the Burma Road for three months. This was to stop war supplies from reaching China. Since Thailand was now aligning with Japan, Britain made this pact with Bangkok to avoid angering Japan.

Luang Wichit wrote many popular plays. These plays praised the idea of a larger "Thai" empire for many ethnic groups. They also criticized the bad things about European colonial rule. There were constant demonstrations in Bangkok against France and for getting back lost lands. In late 1940, small fights broke out along the Mekong border. In 1941, these fights turned into the small Franco-Thai War between Vichy France and Thailand. Thai forces were strong on the ground and in the air. But the Thai Navy lost badly at the battle of Ko Chang. Japan then stepped in to help make peace. The final agreement gave most of the disputed areas in Laos and Cambodia back to Thailand.

World War II

Phibun's standing grew so much that he felt like the true leader of the nation. To celebrate, he promoted himself to field marshal, skipping several ranks.

This caused relations with Britain and the United States to quickly worsen. In April 1941, the United States stopped sending petroleum supplies to Thailand. Thailand's short period of glory ended on December 8, 1941. Japan invaded the country along its southeastern coast and from Cambodia. After trying to resist at first, the Phibun government gave in. It allowed the Japanese to pass through Thailand to attack Burma and invade Malaya. Phibun saw that the Allies were losing in early 1942. He decided to form a military alliance with Imperial Japan.

In return, Japan allowed Thailand to invade and take over the Shan States and Kayah State in northern Burma. Thailand also got back control over the sultanates of northern Malaya. These had been given to Britain in the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909. In January 1942, Phibun declared war on Britain and the United States. However, the Thai ambassador to the United States, Seni Pramoj, refused to deliver the declaration. Seni said Phibun's government was illegal. He formed a Seri Thai (Free Thai) Movement in Washington. Pridi, who was now a mostly powerless regent, led the resistance movement inside Thailand. The former Queen Ramphaiphanni was the official head of the movement in Great Britain.

Secret training camps were set up in faraway places. Most were by the politician Tiang Sirikhanth in the northeast region. There were many camps in Sakhon Nakhon Province alone. Secret airfields also appeared in the northeast. From these, Royal Air Force and United States Army Air Forces planes brought in supplies. They also brought in agents from special operations groups and the Free Thai movement. At the same time, they helped escaped prisoners of war leave. By early 1945, Thai air force officers were working with Allied forces in Kandy and Calcutta.

By 1944, it was clear that the Japanese would lose the war. Their behavior in Thailand had become very arrogant. Bangkok also suffered greatly from Allied bombing. Along with economic problems from losing Thailand's rice export markets, this made the war and Phibun's government very unpopular. In July 1944, Phibun was removed from power by the government, which had been secretly joined by Free Thai members. The national assembly met again and chose the liberal lawyer Khuang Aphaiwong as prime minister. The new government quickly left the British territories that Phibun had taken. It secretly helped the Free Thai movement. At the same time, it pretended to have friendly relations with the Japanese.

The Japanese surrendered on August 15, 1945. Immediately, Britain became responsible for military matters in Thailand. British and Indian troops quickly arrived. They secured the release of surviving POWs. The British were surprised to find that the Japanese soldiers had already been largely disarmed by the Thais.

Britain thought Thailand was partly responsible for the damage to the Allied side. They wanted to treat Thailand as a defeated enemy. However, the US did not agree with what they saw as British and French colonialism. They supported the new Thai government. So, Thailand received little punishment for its role in the war under Phibun.

Post-War Thailand (1946–1957)

Seni Pramoj became prime minister in 1945. He quickly changed the country's name back to Siam. This was a symbol that Phibun's nationalist government was over. However, Seni found it hard to lead a government full of Pridi's loyal supporters. He did not like working with populist politicians from the northeast or new politicians from Bangkok. They, in turn, saw Seni as an elite who did not understand Thailand's political situation. Pridi continued to have power behind the scenes, as he had during the Khuang government. Pridi's strong presence bothered Seni, leading to a personal dislike that hurt Thailand's politics after the war.

After Thailand signed the Washington Accord in 1946, the lands that had been taken after the Franco-Thai War were returned. These included Phibunsongkhram Province, Nakhon Champassak Province, Phra Tabong Province, Koh Kong Province, and Lan Chang Province. They were given back to Cambodia and Laos.

Democratic Elections

Democratic elections were then held in January 1946. These were the first elections where political parties were allowed. Pridi's People's Party and its allies won most of the votes. In March 1946, Pridi became Siam's first prime minister chosen by democratic election. In 1946, he agreed to give back the Indochinese lands taken in 1941. This was the price for Thailand to join the United Nations. All war claims against Siam were then dropped, and Thailand received a lot of aid from the US.

Accession of King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX)

In December 1945, the young King Ananda returned to Siam from Europe. But in June 1946, he was found dead in his bed. The circumstances were mysterious. Three palace servants were tried and executed for his murder. However, there are serious doubts about their guilt. The case remains unclear and is a very sensitive topic in Thailand today. The king was followed by his younger brother, Bhumibol Adulyadej, who became King Rama IX. In August, Pridi was forced to resign. People suspected he was involved in the king's death. Without his leadership, the civilian government struggled. In November 1947, the army, feeling confident again after the problems of 1945, took power. After a temporary government led by Khuang, the army brought Phibun back from exile in April 1948. They made him prime minister. Pridi, in turn, was forced into exile. He eventually settled in Beijing as a guest of the People's Republic of China.

Phibunsongkhram's Second Premiership

Sarit Thanarat

Phibun's return to power happened at the start of the Cold War. This was also when a communist government was set up in North Vietnam. Phibun quickly gained the support of the US. This began a long history of US-backed military governments in Thailand. (The country was again renamed Thailand in July 1949, this time permanently).

Again, political opponents were arrested and tried. Some were executed. During this time, several key figures from the wartime Free Thai underground were killed by the Thai police. This police force was run by Phibun's tough partner Phao Sriyanond. There were attempts by Pridi's supporters to take back power in 1948, 1949, and 1951. The second attempt led to heavy fighting between the army and navy before Phibun won. In the navy's 1951 attempt, known as the Manhattan Coup, Phibun was almost killed. The ship where he was held hostage was bombed by the pro-government air force.

New Constitution in 1949

In 1949, a new constitution was put in place. It created a senate whose members were chosen by the king (which really meant by the government). But in 1951, the government got rid of its own constitution. It went back to the old rules from 1932. This basically removed the national assembly as an elected body. This caused strong opposition from universities and the press. It led to more trials and strict control. However, the government was greatly helped by a post-war economic boom. This boom grew stronger through the 1950s, fueled by rice exports and US aid. Thailand's economy started to become more diverse. The population and city growth also increased.

Power Play

By 1956, it became clear that Phibun, allied with Phao, was losing power. Another strong group, led by Sarit, was gaining influence. This group included royal families and their supporters. Both Phibun and Phao wanted to bring Pridi Banomyong back to Thailand. They wanted to clear his name regarding the mysterious death of King Rama VIII. However, the US government did not approve, and the plan was canceled. In June 1957, Phibun told one of Pridi's sons to tell his father that he wanted him to come back and help the nation. He said he alone could no longer fight the royalists.

Sarit Dictatorship and the Restoration of Monarchy (1957–1963)

By 1955, Phibun was losing his top position in the army. Younger rivals, led by Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat and General Thanom Kittikachorn, were becoming more powerful. To strengthen his position, Phibun brought back the 1949 constitution. He called for elections, which his supporters won. But the army was not ready to give up power. In September 1957, it demanded Phibun's resignation. When Phibun tried to have Sarit arrested, the army staged a peaceful takeover on September 17, 1957. This ended Phibun's career for good.

Sarit brought back the power of the monarchy so well. By the time Thanom ruled, the military and the king worked very closely together. In this period, the Monarchy regained the power it had before the Siamese revolution in 1932.

Cold War and Pro-American Period (1963–1973)

Thanom became prime minister until 1958. Then he gave his place to Sarit, who was the real leader. Sarit held power until he died in 1963. Then Thanom took the lead again.

Sarit and Thanom were the first Thai leaders educated only in Thailand. They were less influenced by European political ideas than Pridi and Phibun. Instead, they were traditional Thai leaders. They wanted to bring back the king's prestige. They also wanted to keep a society based on order, clear ranks, and religion. They believed that army rule was the best way to do this. They also thought it was the best way to defeat communism, which they now linked with Vietnam, Thailand's traditional enemy. The young King Bhumibol, who returned to Thailand in 1951, worked with this plan. The Thai monarchy's high status today began in this time.

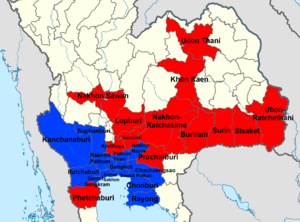

U.S. Military Bases in Thailand

The governments of Sarit and Thanom were strongly supported by the US. Thailand officially became a US ally in 1954. This happened with the creation of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO). When the war in Indochina was between Vietnam and France, Thailand stayed out of it. Thailand disliked both sides. But once it became a war between the US and the Vietnamese communists, Thailand strongly supported the US. It made a secret agreement with the US in 1961. Thailand sent troops to Vietnam and Laos. It also allowed the US to use airbases in eastern Thailand. These bases were used to bomb North Vietnam. Vietnam fought back by supporting the Communist Party of Thailand's uprising. This happened in the north, northeast, and sometimes in the south. There, rebels worked with unhappy local Muslims. After the war, Thailand had close ties with the US. It saw the US as a protector from communist revolutions in nearby countries. The Seventh and Thirteenth US Air Forces were based at Udon Royal Thai Air Force Base.

Agent Orange

Agent Orange is a chemical used by the U.S. military. It is a herbicide and defoliant. It was part of their program to use chemicals to clear plants during the Vietnam War. Agent Orange was tested by the United States in Thailand during the war. Buried drums were found and confirmed to be Agent Orange in 1999. Workers who found the drums became sick. This happened while they were improving the airport near Hua Hin District, south of Bangkok.

A government report from 1973, which is now public, suggests that a lot of herbicides were used. They were sprayed around the edges of military bases in Thailand. This was to remove plants that could hide enemy forces.

Development During the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War sped up the modernization and Westernization of Thai society. The American presence and exposure to Western culture affected almost every part of Thai life. Before the late 1960s, only a small group of educated people had full access to Western culture. But the Vietnam War brought the outside world face to face with many Thais like never before. With US money boosting the economy, industries like services, transportation, and construction grew hugely. The traditional rural family unit started to break down. More and more rural Thais moved to cities to find new jobs. This led to a clash of cultures. Thais were exposed to Western ideas about fashion, music, values, and moral standards.

The population began to grow very quickly as the standard of living rose. Many people started moving from villages to cities, especially to Bangkok. Thailand had 30 million people in 1965. By the end of the 20th century, the population had doubled. Bangkok's population had grown ten times since 1945 and tripled since 1970.

More educational opportunities and access to mass media increased during the Vietnam War years. Smart university students learned more about ideas related to Thailand's economy and political systems. This led to a new wave of student activism. The Vietnam War period also saw the growth of the Thai middle class. This group slowly developed its own identity and awareness.

Economic development did not bring wealth to everyone. During the 1960s, many poor people in rural areas felt more and more unhappy. They were disappointed with how the central government in Bangkok treated them. Efforts by the Thai government to develop poor rural regions often did not help as intended. Instead, they made farmers more aware of how bad their situation really was. It was not always the poorest people who joined the anti-government uprising. Increased government presence in rural villages did little to improve things. Villagers faced more harassment from the military and police. They also saw more corruption among government workers. Villagers often felt cheated when government promises of development were not kept. By the early 1970s, unhappiness in rural areas had turned into a farmers' activist movement.

Peasant's Revolution

The farmers' movement started in the regions just north of the central plains and the Chiang Mai area. These were not the areas where the uprising was most active. When these regions were organized into the central Siamese state during King Chulalongkorn's reign, the old local nobles were allowed to take large amounts of land. The result was that by the 1960s, almost 30% of families had no land.

In the early 1970s, university students helped bring some local protests to the national stage. The protests focused on losing land, high rents, harsh police actions, corruption among government workers and local elites, poor infrastructure, and widespread poverty. The government agreed to set up a committee to hear farmers' complaints. In a short time, the committee received over 50,000 requests. This was more than it could possibly handle. Officials said many of the farmers' demands were unrealistic and too big.

Political Environment

Thailand's political situation changed little during the mid-1960s. Thanom and his main deputy Praphas kept a strong hold on power. Their alliance became even stronger when Praphas's daughter married Thanom's son Narong. However, by the late 1960s, more people in Thai society openly criticized the military government. They saw it as increasingly unable to solve the country's problems. It was not just student activists. The business community also began to question the government's leadership and its relationship with the United States.

Thanom faced growing pressure to loosen his control. The king commented that it was time for parliament to be brought back and a new constitution to be put in place. After Sarit had suspended the constitution in 1958, a committee was set up to write a new one. But almost ten years later, it was still not finished. Finally, in 1968, the government issued a new constitution and planned elections for the next year. The government party, founded by the military leaders, won the election. Thanom remained prime minister.

Surprisingly, the assembly was not completely controlled. Some members of parliament (mostly professionals like doctors, lawyers, and journalists) began to openly challenge some government policies. They showed evidence of widespread government corruption in many large projects. As a new budget was being discussed in 1971, it seemed that the military's demand for more money might be voted down. Rather than face such a defeat, Thanom carried out a takeover against his own government. He suspended the constitution and dissolved parliament. Once again, Thailand returned to absolute military rule.

This strong-arm approach had worked for Phibun in 1938 and 1947, and for Sarit in 1957–58. But it would not work this time. By the early 1970s, Thai society as a whole had become more politically aware. They would no longer accept unfair authoritarian rule. The king, using various holidays to give speeches on public issues, became openly critical of the Thanom-Praphas government. He expressed doubts about using extreme violence to fight the uprising. He mentioned the widespread corruption in the government. He also said that takeovers should become a thing of the past in Thai politics.

The military government started to face growing opposition from within the military itself. Thanom and Praphas were very busy with their political roles. They became less involved in directly controlling the army. Many officers were angry about Narong's quick promotion. They also felt he was destined to be Thanom's successor. To these officers, it seemed that a political family was being created.

The 1973 Democracy Movement

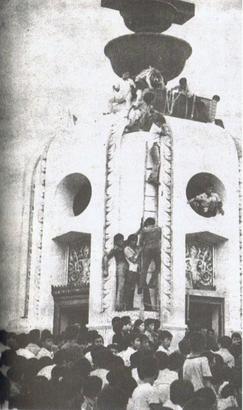

Student demonstrations had started in 1968. They grew bigger and more numerous in the early 1970s. This happened even though political meetings were still banned. In June 1973, nine Ramkhamhaeng University students were expelled. They had published an article in a student newspaper that criticized the government. Soon after, thousands of students protested at the Democracy Monument. They demanded that the nine students be allowed back in school. The government ordered universities to close. But shortly after, it allowed the students to re-enroll.

In October, another 13 students were arrested. They were accused of planning to overthrow the government. This time, workers, business people, and other ordinary citizens joined the student protesters. The demonstrations grew to several hundred thousand people. The issue expanded from just releasing the arrested students. People now demanded a new constitution and a new government.

On October 13, the government released the arrested people. Leaders of the demonstrations, like Seksan Prasertkul, called off the march. This was in line with the king's wishes, who was publicly against the democracy movement. In a speech to graduating students, he criticized the pro-democracy movement. He told students to focus on their studies and leave politics to older people (the military government).

As the crowds were breaking up the next day, on October 14, many students could not leave. The police had tried to control the flow of people by blocking the southern route to Rajavithi Road. Trapped and surrounded by the angry crowd, the police used tear gas and fired guns.

The military was called in. Tanks rolled down Rajdamnoen Avenue. Helicopters fired down at Thammasat University. Some students took over buses and fire engines. They tried to stop the tanks by crashing into them. With chaos in the streets, King Bhumibol opened the gates of Chitralada Palace to the students who were being shot by the army. Despite orders from Thanom to increase military action, army commander Kris Sivara pulled the army back from the streets.

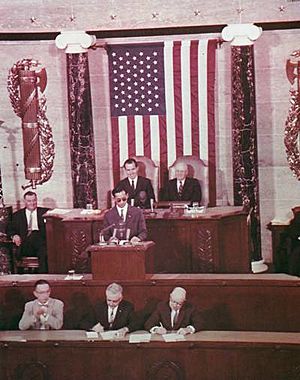

The king criticized the government's inability to handle the protests. He ordered Thanom, Praphas, and Narong to leave the country. He also notably criticized the students' supposed role. At 6:10 PM, Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn resigned from his post as prime minister. An hour later, the king appeared on national television. He asked for calm. He announced that Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn had been replaced by Dr. Sanya Dharmasakti, a respected law professor, as prime minister.

See also

- History of Thailand (1973–2001)

- History of Thailand

- Constitutions of Thailand

- Military history of Thailand

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |