History of Tobago facts for kids

The history of Tobago tells the story of this island, from its very first human settlements in ancient times, all the way to its current role as part of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. Long ago, indigenous people lived here. Then, in the 1500s and early 1600s, the Spanish raided the island for slaves. Later, countries like the Dutch, British, French, and Courlanders tried to set up colonies starting in 1628. Most of these attempts failed because the local people fought back. After 1763, British settlers turned Tobago into a place for large farms called plantations, using enslaved Africans to work them.

Tobago came under French control in 1781 during a war between Britain and France. It returned to British control in 1793 during another war, but was given back to France in 1802. The British took the island back in 1803 and kept it until Trinidad and Tobago became independent in 1962.

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, Tobago's economy relied completely on slavery. The lives of enslaved Tobagonians were controlled by the Slave Act. Slavery ended in 1838. Because there wasn't enough money to pay workers, plantation owners in Tobago started using a system called metayage, which was like sharecropping. This system was common until the late 1800s.

When sugar prices dropped, Tobago joined with other British colonies in the Caribbean. This also meant the end of its own self-government. In 1889, Tobago combined with Trinidad to form the colony of Trinidad and Tobago. This new colony gained independence in 1962. Tobago got its own self-government back in 1980 with the creation of the Tobago House of Assembly.

Contents

First People of Tobago

Tobago was first settled a very long time ago, in what's called the Archaic period. These early people likely came from Trinidad. The oldest settlements are in the southwest of the island, close to the Bon Accord Lagoon. They belong to a group known as the Milford complex. This name comes from a pile of shells found near Milford, Tobago.

These first Tobagonians were hunters and gatherers. They probably also grew some plants. They ate edible roots, palm starch, and seeds. They also fished and hunted sea turtles, shellfish, crabs, and land animals like peccaries and agoutis. These people are linked to the Ortoiroid people. No pottery has been found at their sites.

Archaeologists aren't exactly sure how old the Milford complex sites are. Tools found at Milford and other places in southwest Tobago are from between 3500 and 1000 BCE. These tools are similar to ones found in Trinidad. This suggests the Tobago sites are probably from the older part of that time range.

Around the first century CE, people called Saladoid settled in Tobago. Like the Ortoiroid people before them, they are thought to have come from Trinidad. They brought with them the skills of making pottery and farming. They likely introduced crops such as cassava, sweet potatoes, Indian yam, tannia, and corn. Later, their culture changed a bit when the Barrancoid culture arrived. Barrancoid people settled in the Orinoco Delta around 350 CE and in south Trinidad around 500 CE. This led to new pottery styles in Trinidad. These new ideas reached Tobago through trade or by new settlers.

After 650 CE, the Troumassoid culture replaced the Saladoid culture in Tobago. Before, Tobago and Trinidad shared similar cultures. But now, they became different. Trinidad followed the Arauquinoid culture, while Tobago became more like the Windward Islands and Barbados. People still ate similar foods as in Saladoid times. However, there were fewer peccary bones found. This suggests that these larger animals might have been over-hunted. The Troumassoid traditions were once thought to be linked to the Island Caribs. But now, this is connected to another pottery style called Cayo. No archaeological sites in Tobago are only from the Cayo tradition.

Early European Contact

Christopher Columbus saw Tobago on August 14, 1498, during his third voyage. He didn't land on the island. He named it Belaforme, which means "beautiful" from a distance. A Spanish friar, Antonio Vázquez de Espinosa, wrote that the Kalina (mainland Caribs) called the island Urupaina. This was because it looked like a big snail. The Kalinago (Island Caribs) called it Aloubaéra. This name might refer to a giant snake believed to live in a cave on Dominica. The name Tabaco was first written in a Spanish royal order in 1511. This name refers to the island's shape, which looked like the thick cigars smoked by the Taíno people of the Greater Antilles.

Tobago's location between the Lesser Antilles and South America made it an important meeting point. It connected the Kalinago of the Lesser Antilles with their Kalina friends and trading partners in the Guianas and Venezuela. In the 1630s, the Kalina people lived in Tobago. Nearby Grenada was shared by the Kalina and Kalinago.

The Spanish raided Tobago to capture people for slave labor in the pearl fisheries on Margarita. A Spanish royal order from 1511 allowed the Spanish in Hispaniola to wage war and enslave people from the Windward Islands, Barbados, Tobago, and Trinidad. After a permanent Spanish settlement was built in Trinidad in 1592, Tobago became a main target for their slave raids. These raids from Margarita and Trinidad continued until at least the 1620s. They greatly reduced the number of people living on the island.

First European Settlements

In 1628, Jan de Moor, a leader from Vlissingen in the Netherlands, got the right to colonize Tobago from the Dutch West India Company. He started a colony of 100 settlers called Nieuw Walcheren at Great Courland Bay. They built a fort, Nieuw Vlissingen, near where Plymouth is today. The colony's goal was to grow tobacco for export. The settlers were also allowed to trade with the local people.

The local people of Tobago were not friendly to the colonists. In 1628, a warship from Zeeland lost 54 men in a fight with a group of Amerindians. The town was also attacked by Kalinago from Grenada and St. Vincent. The colony was left empty in 1630. But it was started again in 1633 with 200 new settlers. The Dutch traded with the Nepoyo in Trinidad. They also built strong trading posts on Trinidad's east and south coasts. They joined Hierreyma, a Nepoyo chief, in his fight against the Spanish. In return, the Spanish destroyed the Dutch posts in Trinidad. Then, they gathered a force and captured the Dutch colony in Tobago in December 1636. The Dutch prisoners were sent to Margarita, where most of them were executed. This was against the terms of their surrender.

English settlers from Barbados tried to start a colony in Tobago in 1637. But the Caribs attacked them soon after they arrived, and the colony was abandoned. After this, several attempts were made to settle the island by colonists supported by the Earl of Warwick. In 1639, a group of "a few hundred" settlers started a colony. But they left in 1640 after attacks by Kalinago from St. Vincent. A new group of colonists arrived in 1642. They started tobacco and indigo plantations. This settlement was abandoned because of Carib attacks and a lack of supplies. A fourth English colony was started in 1646 but only lasted a few months.

Courlander and Dutch Colonies

Duke Friedrich Kettler of Courland tried to start a colony on Tobago in 1639, but it failed. Duke Friedrich's successor, Jacob Kettler, made another attempt in 1642. He sent a few hundred colonists from Zeeland led by Cornelius Caroon. This settlement was attacked by Kalinago from St. Vincent. The survivors were taken to the Guiana coast by Arawaks from Trinidad.

A new colony was started at Great Courland Bay in 1654. It was near the ruins of the old Dutch fort at Plymouth. The fort was rebuilt and renamed Fort Jacobus. The settlement around the fort was called Jacobusstadt. It had the first Lutheran church in the Caribbean. The settlers were a mix of Dutch and Courlanders, led by Willem Mollens. They renamed the island Neu Kurland. A few months later, a Dutch colony was started on the other side of the island. This was supported by brothers Adriaen and Cornelius Lampsins. They were rich merchants from Walcheren in Zeeland. The Dutch named their settlement Lampsinsstad. It was built where the capital, Scarborough, is now. When the Courlanders found out about the Dutch colony, they attacked it. They forced the Dutch settlers to accept Couronian rule. Lampsinsstad grew as Jews, French Huguenots, and Dutch planters from Brazil arrived. These planters brought African slaves and Amerindian allies with them after being forced out of Brazil by the Portuguese. By 1662, the Dutch settlement had 1250 white settlers and between 400 and 500 enslaved Africans.

The Courlander settlement tried to stay friendly with the local Kalina people. But it was attacked by Kalinago from St. Vincent and Arawaks from Trinidad. From about 500 settlers, the colony shrank to 50 people by 1658. In 1659, while Courland was at war in Europe, the Dutch colony rebelled and took control of the island. Fort Jacobus was renamed Fort Beveren, after Hubert van Beveren, the governor of the Dutch colony.

In 1666, during the Second Anglo-Dutch War, Lampsinsstad was captured and looted by pirates from Jamaica. English forces from Barbados then took the fort. Later, French forces from Grenada captured it. But the Dutch recaptured it in 1667. New settlers from the Netherlands restarted the colony in 1668. But Nepoyo from Trinidad attacked them. They fought off the attacks with help from Tobagonian Kalina. However, they were attacked again by Kalinago from St. Vincent. When the Third Anglo-Dutch War started, the colony was captured and looted by people from Barbados.

After that war ended, a new Dutch colony was started in 1676. But the French attacked it in March of the next year. A naval battle happened, causing many losses on both sides. The French forces left, but came back the next year. They captured the island and destroyed the settlement. New Courlander attempts to start a colony in Tobago in 1680 and 1681 were given up by 1683. A final Courlander attempt to settle the island in 1686 was mostly abandoned by 1687. The last time the colony was mentioned was a small group of settlers seen by a Danish ship in 1693.

Neutral Tobago

Both Britain and France claimed Tobago. But after the 1690s, the island was left to its indigenous people. European settlement in Tobago had been largely "stopped" by the combined resistance of the local Kalina people and the Kalinago from the Lesser Antilles. The Treaty of Aix-la-Chappelle in 1748 declared Tobago a neutral territory. Amerindians from Venezuela, who wanted to avoid being forced into mission villages, and Island Caribs from St. Vincent, who wanted to escape conflict with the Black Caribs, were among the groups who settled there during this time.

Plantation Economy

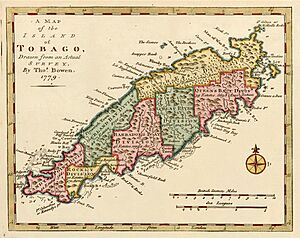

The Treaty of Paris in 1763 ended Tobago's neutral status. It brought the island under British control. A plantation economy quickly started on the island. The island was surveyed, divided into plots of 100 to 500 acres, and sold to planters. Between 1765 and 1771, over 50,000 acres of land were sold by the Crown for more than £167,000. Thanks to Soame Jenyns, a government official, the upper parts of the Main Ridge were kept as "Woods for the Protection of the Rains." These areas remained untouched and wild.

The old Dutch town of Lampsinsstad was renamed Scarborough in 1765. It became the capital of Tobago in 1779. To protect Scarborough, the British built Fort King George on a hill overlooking the town. The number of British settlers and enslaved Africans grew quickly. The production of sugar, cotton, and cocoa increased a lot. A colonial constitution was given, and an elected House of Assembly was created. Each parish had one elected member. The government was controlled by the Governor-in-Chief of the Windward Islands, who was based in Grenada.

A money crisis in Britain in 1772 caused several merchant banks to go bankrupt. West Indian planters relied on these banks for loans. The loss of easy loans made things hard for planters in Tobago. In 1776, they still owed the Crown £69,000 for land they bought, plus £30,000 in interest. They also owed another £740,000 to merchant banks. The start of war with the American colonies made the problem worse. It drove up shipping and insurance costs for the planters. France joining the war in 1778 made the situation even harder.

While the white and African populations grew fast, the indigenous population decreased. In 1777, there were "a few hundred" Amerindians. But by 1786, there were only 24. Many left for the north coast of Trinidad, settling in the Toco area. The last records of Amerindians in Tobago are from Sir William Young, who was Governor of Tobago until 1815.

French Rule

In 1781, as part of the Anglo-French War, France captured Tobago. The island was given to France in 1783 under the Treaty of Paris. This treaty kept the existing constitution and laws. It also allowed British inhabitants to keep their property and religion. The capital, Scarborough, was renamed Port Louis in 1787. Fort King George was renamed Fort Castries.

Elections in 1784 left the Assembly controlled by British planters. In 1785, they refused to fund the island's government. They said their financial situation was too difficult. In response, the French government demanded the Assembly pay 200,000 livres tournois each year. They agreed to this in 1786.

A new Colonial Assembly was created. It had two elected members from each parish and two from Port Louis. It also had four unelected members: the governor and three other senior government officials. With this new structure and much less independence, the Assembly mainly approved orders sent by the French government.

Some British settlers left the island after 1783, but most stayed. Few French people moved to the island, so the white population remained mostly British. Between 1782 and 1790, the white population grew from 405 to 541. The free coloured population (including both black and mixed-race people) rose from 118 to 303. The enslaved population grew from 10,530 to 14,171. This was mostly due to bringing in new enslaved people, as more enslaved people died than were born.

According to the 1790 census, Tobago had 15,019 people. Of these, 14,170 were enslaved. The white population had more men: 434 of the 541 whites were male. The free non-white population had more women: 198 of the 303 free people of colour were female. This partly shows that twice as many enslaved women were freed as enslaved men.

In 1785, cotton was the main crop in Tobago. 12,491 acres were used for cotton, and 1,584,000 pounds were exported. Sugar cane was grown on 4,241 acres. 1,102 long tons of sugar and 133,600 imperial gallons of rum were exported. By 1791, cotton exports had fallen to 516,000 pounds. But sugar (1,991 long tons) and rum exports (261,840 imperial gallons) had almost doubled.

The French Revolution in 1789 caused a split among the French people on the island. Some supported the king, and others supported the revolution. A new governor sent to bring back royal authority in 1792 left for Grenada in 1793. He was replaced by a revolutionary governor.

Return to British Control

When war broke out between Britain and Revolutionary France in 1793, Britain was able to recapture the island. British forces from Barbados, led by Cornelius Cuyler, landed at Great Courland Bay on April 14. They attacked the French forces at Fort Castries. The French forces surrendered after the British attacked from two sides. Cuyler brought back the British colonial constitution that had been in place before the French took over in 1781.

Tobago was given back to France in 1802 under the Treaty of Amiens. But the British recaptured it when war started again in 1803. France officially gave Tobago to Britain under the terms of the 1814 Treaty of Paris.

The Haitian Revolution stopped sugar exports from the former French colony of Saint-Domingue. Planters in Tobago were able to take advantage of this. They greatly increased sugar production. In 1794, 5,300 long tons of sugar were exported from Tobago. This rose to a high of 8,890 long tons in 1799.

Slavery in Tobago

Tobago's economy in the late 1700s and early 1800s depended completely on slavery. Enslaved people worked on plantations and in homes. They also worked as skilled craftspeople, on fishing boats, and merchant ships. They even helped defend the island's forts. Sugar production was the most important part of the island's economy. More than 90% of the enslaved population worked on sugar estates. The rest worked in Scarborough or Plymouth, mostly as house servants.

The 1790 census counted 14,170 enslaved people in Tobago. By 1797, the enslaved population grew to 16,190. It reached 18,153 in 1807, the year the slave trade was abolished. Since more enslaved people died than were born, the enslaved population decreased to 16,080 by 1813.

Slavery was controlled by the Slave Act of 1775. Enslaved people were seen as property, with no rights of their own. But they were also humans with "reasoning and will." The Slave Act, like other slave laws in the British West Indies, aimed to make sure that enslaved people, while acting as humans, still functioned as property. Hitting or hurting a white person, hurting another enslaved person, setting fire to sugar cane fields or buildings, or trying to leave the island were all crimes. These could be punished by death, being sent away to another place, or any other punishment a judge chose.

Enslaved people had to carry passes that allowed them to be away from their owner's plantation. If found without a pass, they could be arrested as runaways. Hiding runaways was a crime, even for white people. Any plantation left empty for more than six months, and food crops growing on them, could be destroyed. This was to stop runaway enslaved people from gathering there.

Plantations had to plant 1 acre of food crops for every five enslaved people to prevent food shortages. Over time, this changed. Enslaved people were allowed to grow their own food gardens. Enslaved people were given Sundays, and on larger plantations, Thursdays, to work on their gardens. They could eat or sell what they grew as they wished. On plantations with larger gardens, enslaved people were expected to use their own money to buy meat and fish. Where gardens were smaller, the plantation owner provided these foods. Enslaved people in towns could not grow gardens. This was because land wasn't available, and domestic workers didn't have the time.

After reaching its highest point in 1799, sugar production slowly declined. Planters' income fell even faster as sugar prices dropped. Prices went from 87 shillings per hundredweight in 1799 to less than half that (32 to 38 shillings) in 1807. The abolition of the slave trade in 1807 put more pressure on planters. Because more enslaved people died than were born, the enslaved population could not grow on its own. This made the cost of enslaved people go up, which affected the cost of producing sugar.

Falling sugar prices led to a decline in the economies of the West Indian islands, including Tobago. After slavery ended in 1838, economic conditions did not get better. The price of sugar fell from about 34 shillings per hundredweight in 1846, to 23 shillings in 1846, and 21 shillings in 1854. The 1846 Sugar Duties Act removed protections for British West Indian sugar. This forced it to compete with sugar grown in other countries, which was cheaper to produce, and beet sugar, which received government help. The main way the island's government made money was through customs duties. So, the falling value of sugar exports meant less money for the government. In 11 of the 21 years between 1869 and 1889, the government spent more money than it earned. The bankruptcy in 1884 of A.M. Gillespie and Company, a London-based company that provided loans, marketing, and shipping to many planters, was a big blow to Tobago's economy.

Because there wasn't enough money to pay workers, planters in Tobago turned to metayage. This was a form of sharecropping that the French had brought to the Windward Islands. In this system, planters provided the land, young plants, transport, and machines to make sugar. The workers (called metayers) provided the labor to grow and harvest the sugar cane. In Tobago, metayers often had to provide the labor to operate the sugar mill. The sugar produced was shared between the landowner and the metayers. Usually, half the sugar went to the metayer. But if the landowner provided a field of ratoons (canes that grew back from old roots), the metayer's share was only one-third to one-fifth of the sugar.

This system first started in Tobago in 1843. By 1845, it was widely used. While the system was mostly abandoned in other Windward Islands by the 1860s, it remained the main way of producing sugar in Tobago until the end of the 1800s, when sugar production finally stopped.

Joining with Trinidad

As Tobago's economy got worse, its importance to the British government also declined. To lower the cost of ruling the island, the British government wanted to unite Tobago with nearby islands into one administrative unit. In 1833, Tobago, Grenada, and St. Vincent were placed under the authority of the Governor of Barbados. But this didn't change much for the Assembly's power. After slavery ended, the elected members participated less in the Assembly's work. With limited participation and many absences, the Assembly voted to abolish itself in 1874. It was replaced by a single chamber called the Elected Legislative Council. This chamber had 14 members: six nominated by the Governor and eight elected by the planters. The planters first objected to losing power. But this changed after the Belmanna riots in 1876. Facing growing unrest from the black population, the planters voted to end their representative government and make the island a Crown colony.

The collapse of A.M. Gillespie and Company in London in 1884 further weakened Tobago's economy. In 1885, the British government combined Tobago, Grenada, St. Vincent, and St. Lucia into one group called the Windward Islands. This was a loose union that put the islands under a single governor, but kept their local institutions.

In 1887, the British Parliament passed the Trinidad and Tobago Act. This law allowed Trinidad and Tobago to unite. The goal of this union was to shift the cost of running Tobago from the British crown to the richer colony of Trinidad. On November 17, 1888, the Act was announced, and the union began on January 1, 1889. The islands were united under one administrative structure, based in Port of Spain. They also had a single governor, who had previously been the governor of Trinidad. The last bit of self-government, the Financial Board, had three elected members, two members appointed by the governor, and a commissioner also appointed by the governor. The governor could dissolve the board without asking the people of Tobago. Legally, the Supreme Court in Trinidad gained power over Tobago and could appoint magistrates. Tobago's status was lowered to that of a ward in 1899. The warden of Tobago became the chief government official on the island.

Because Tobago had no one to represent it on the Legislative Council, people called for someone to be appointed to speak for Tobago's interests. In 1920, Governor John Chancellor invited T. L. M. Orde, manager of the Louis D'Or Estate in Tobago, to join the council. But Orde said no because it would mean being away from the island for long periods. A.H. Cipriani, a Trinidad resident who owned large coconut estates in Tobago, was appointed instead. Between 1920 and 1925, people living in Trinidad represented Tobago's interests. Black Tobagonians wanted to serve on the council, but the political leaders did not accept this idea.

Representation in Government

In 1925, the Legislative Council grew from 21 to 25 members, including seven elected members. Tobago gained its first elected representatives since 1877, when Crown colony government started. Only literate men aged 21 or older could vote, and they had to meet certain property and income requirements. The requirements for candidates were even stricter. The elections took place on February 7, 1925. Only 5.9% of the population could vote. In Tobago, only 547 out of 1,800 eligible voters actually voted. James Biggart, a black Tobagonian pharmacist, was elected to represent Tobago in the Legislative Council.

On the legislative council, Biggart pushed for better roads, schools, and communication by sea between the islands. Biggart was able to improve Tobago's infrastructure and connections between the islands. In 1925, Bishop's High School was established in Tobago by the Anglican Church, and it received money from the government. Biggart held the Tobago seat until he died in 1932. A white planter and businessman, Isaac A. Hope, won the special election to take Biggart's place. In the 1938 elections, Hope was replaced by George de Nobriga.

The County Council Ordinance of 1946 divided Tobago into seven areas, each with two councillors. When all adults gained the right to vote in 1946, A.P.T. James was elected to the Legislative Council. James was a strong supporter of Tobago. He pushed for more development in infrastructure. He successfully got running water, schools, health centers, a deep-water harbor, and in 1952, electricity. He argued for more representation for Tobago in the legislature. He also wanted separate representation in the West Indies Federation, and later, full independence. James lost the 1961 general elections to A.N.R. Robinson, who was a founder of the ruling People's National Movement (PNM).

Economy After Union

After joining with Trinidad, Tobago's economy remained undeveloped. Most people were peasant farmers. They grew mostly food crops and earned extra money working on coconut and cacao estates. These crops replaced sugar as the island's main exports. Wages were very low. This allowed plantation owners (mostly 50 to 60 white families) to make "substantial profits" even when prices for goods were very low.

In the 1930s, white planters started renting their estate houses to winter visitors. Later, they invested in hotels and guest houses. In the 1950s, tourism began to replace farming as Tobago's main employer and economic driver.

Independence and Self-Governance

In 1956, Crown colony government in Trinidad and Tobago was replaced by internal self-government. The 1956 general elections were won by the newly formed People's National Movement, led by Eric Williams. Williams was appointed chief minister, but the governor remained head of the Executive Council. When the West Indies Federation was formed in 1958, the Williams government gained more direct control over policies for Trinidad and Tobago.

In 1958, a Department of Tobago Affairs was created, led by a permanent secretary. In 1962, Trinidad and Tobago became an independent nation. In 1964, the Department of Tobago Affairs became a cabinet-level position. The Ministry of Tobago Affairs was created, partly to help with recovery from Hurricane Flora, which had badly damaged Tobago in 1963.

Economic Development

In 1957, Williams introduced the Tobago Development Program. This was an economic plan designed to fix "many years of neglect and betrayal" of Tobago by the Trinidad-based government. Successfully developing Tobago was seen as important to show that Trinidad and Tobago could lead the West Indies Federation. By showing it could help Tobago grow, Williams wanted to show it could do the same for other smaller members of the federation. While the Williams government increased development spending in Tobago compared to the previous government, only about 3% of the 1957 budget went to projects in Tobago. Between 1958 and 1962, Tobago's share of the development budget was also less than 7%, even though the goal was to give Tobago's development high priority.

Hurricane Flora

On September 30, 1963, Tobago was hit by Hurricane Flora. This storm caused 30 deaths. About half of the island's homes were so damaged they couldn't be lived in. The main export crops—coconuts, cocoa, and bananas—were badly damaged. A large part of the fishing fleet was also destroyed. Despite government money for farming recovery, the importance of farming decreased while tourism grew. The number of hotel and guest house rooms increased from 185 in 1960 to 448 in 1972, and to 651 by 1982.

Secession Movement

Starting in 1969, Rhodil Norton, a medical doctor and president of the Buccoo Reef Association (a group of tour guides), began calling for Tobago to leave Trinidad and Tobago. His calls faced strong opposition from Trinidadian society and the ruling PNM government. This included Basil Pitt, the Member of Parliament (MP) for Tobago West. Other Tobagonians, while not wanting to secede, felt that Tobago was not treated fairly and that the central government had not kept its promises to Tobago.

Even though some claimed Tobago was neglected, Tobagonians were well represented in government. Both Pitt and Robinson (the MP for Tobago East) held ministerial positions in the PNM government. The Prime Minister, Williams, was also in charge of the Ministry of Tobago Affairs. In response to these calls for secession, the government increased its investments in Tobago. Despite this, talk of secession continued. The Tobago Emancipation Action Committee, led by Norton, made one such call for secession in 1970. This led the police to watch the group closely.

Black Power Movement

Independence meant that the economy was still controlled by the rich. In 1970, 75% of the best land in Tobago was reportedly owned by local wealthy people or foreigners. The continuation of old colonial ways after independence made people unhappy with the ruling PNM government. Inspired by a mix of Marxism and Garveyism, the Black Power movement was a response to both racism and colonialism.

The arrest and trial of students from Trinidad and Tobago after the Sir George Williams affair in Montreal, Canada, caused protests in Port of Spain. These protests soon spread across the country. In Tobago, protesters demanded an end to strip-tease shows for tourists that employed local teenagers. They also wanted public access restored to the beaches at Pigeon Point and Bacolet. Between 12,000 and 15,000 people took part in a march to Charlotteville. School children in Roxborough organized an 18-mile march to Scarborough.

On April 21, 1970, with ongoing unrest, the Government of Trinidad and Tobago declared a state of emergency. Most of the Black Power movement's leaders were arrested. When asked to help restore order, the Trinidad and Tobago regiment rebelled. But the rebels surrendered after ten days.

Rise of the DAC

On September 20, 1970, Robinson resigned from the PNM. His resignation came after the Black Power uprising earlier that year. He said that the Prime Minister abused his power as one reason for leaving. Robinson had been accused of putting his party's support ahead of Tobago's interests. Now, he was free from those obligations. He formed the Action Committee of Dedicated Citizens (ACDC). He joined forces with the opposition Democratic Labour Party (DLP) to run in the 1971 general elections. On April 3, 1971, ACDC became a political party, the Democratic Action Congress (DAC). Its platform included a strong plan for economic development and self-government for Tobago. Because of worries about voting machines and problems in the election process, the DLP and DAC boycotted the 1971 elections. The PNM won all the seats in Tobago and Trinidad.

In the 1976 general elections, the DAC won both seats in Tobago. Robinson won the Tobago East seat, while Winston Murray won Tobago West. Two months after the election, Williams closed the Ministry of Tobago Affairs. He moved its responsibilities back to other government ministries. In Tobago, this was seen as punishment for the island abandoning the PNM.

Internal Self-Government

With the Ministry of Tobago Affairs closed, Robinson and Murray argued in Parliament for internal self-government in Tobago. The main opposition party in Parliament, the United Labour Front, supported these efforts. After a long and difficult debate, the Tobago House of Assembly (THA) bill was passed on September 12, 1980. Elections on November 24, 1980 saw 63.5% of eligible voters participate. The DAC won eight of the 12 seats in the Assembly, with the PNM winning the other four. The Assembly met for the first time on December 4, 1980. Robinson was elected chair of the THA.

The creation of the THA gave Tobago internal self-government. However, the Assembly was still subject to the central government. The THA bill allowed the Assembly to be cancelled by a two-thirds majority in Parliament. It also left the THA financially dependent on money from the central government. A revised bill, Act 40 of 1996, made the THA permanent. It created the position of Presiding Officer and gave the Chief Secretary the right to work directly with the Cabinet on issues related to Tobago.

Robinson Era

Between 1980 and 2003, Castara–born A.N.R. Robinson played a very important role in the politics and government of Trinidad and Tobago. He was first Chairman of the THA, then Prime Minister, and finally President of Trinidad and Tobago.

Before the 1981 general elections, the DAC, the ULF, and the Tapia House Movement decided to work together for the election. The three parties put forward their own candidates. But they agreed not to compete for the same seats. The DAC ran for eight of the 36 seats in Parliament. However, they only won the two Tobago seats. After the election, the three parties made their relationship official and worked under the name "the Alliance." The Alliance then joined with a fourth party, the Organisation for National Reconstruction, to run in the 1983 local government elections. On September 8, 1985, the four parties dissolved and formed a new party, the National Alliance for Reconstruction (NAR), with Robinson as its leader. The NAR defeated the PNM in the 1986 general elections, and Robinson became the third person to serve as Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago.

The Robinson government invested a lot in Tobago. They completed the Scarborough Deep Water Harbour. They also made the runway at the Crown Point Airport longer. This allowed bigger jets and direct international flights to Tobago. They also improved ferry service between Port of Spain and Scarborough.

Disagreements within the NAR government and the 1990 Jamaat al Muslimeen coup attempt weakened the government. It lost the 1991 general elections to the PNM, led by Patrick Manning. The NAR was left with only the two Tobago seats. The 1995 general elections resulted in a 17–17 tie between the Manning–led PNM and the United National Congress, led by Basdeo Panday. Robinson's NAR still held the two Tobago seats. This meant they could form a coalition government with either party. The NAR chose to work with the UNC and formed a coalition government. Panday became Prime Minister, and Robinson held the position of Minister Extraordinaire with special responsibility for Tobago. In 1997, Robinson resigned from Parliament and was elected President of Trinidad and Tobago. He retired from the presidency in 2003.

See also