History of aviation in Canada facts for kids

The history of aviation in Canada began with the first manned flight in a balloon at Saint John, New Brunswick in 1840. The story of flying in Canada was shaped by big dreams, national and international politics, money, and new technology. Experimental aviation started in Canada with the test flights of Bell's Silver Dart in 1909. This was just a few years after the famous flight of the Wright Brothers in 1903. Soon, planes were used in wars. Many Canadians flew for the British Royal Flying Corps and Royal Air Force during the First World War.

After the war, planes changed from being expensive toys to important tools. They were especially useful for exploring and developing Canada's North. Canadians who had learned to fly during the war used their skills for peaceful jobs. Airplanes helped connect communities far apart in the North. They also gathered information about Canada's natural resources. Planes were as important for opening up the North as railways were for opening the West in the century before. Between the two World Wars, many small local airlines started. Canada didn't have a national plan for transportation. This delayed the creation of a national carrier until Trans Canada Airlines (now Air Canada) was founded in 1937.

World War II pushed technology forward. It also made Canadian factories leaders in building aircraft. Canadian airspace and facilities helped train over 100,000 aircrew from the Commonwealth. The wartime facilities also supported the growth of commercial flying.

The Jet Age made air travel common for many Canadians. It took the place of passenger trains. When airlines were deregulated (meaning less government control), new companies competed with the older airlines. Low profits and tough competition led to times of growth and times of failure.

Today, aviation is a key part of Canada's economy. Regular passenger flights, air mail, and air freight connect Canadian cities and cities worldwide. General aviation helps with medical emergencies, air photography, and supporting resource development.

Early Flights: Balloons and Airships

In August 1840, Louis Anselm Lauriat made the first balloon flight in Canada. He flew his balloon, Star of the East, in Saint John, New Brunswick.

On September 9, 1856, a French aeronaut named Eugène Godard flew a balloon called Canada. This was the first aircraft ever built in Canada. He carried three passengers from Montreal to Pointe-Olivier, Quebec. This was Canada's first successful passenger flight.

Balloon and dirigible (blimp) shows were popular in the early 1900s. The first flight of a power-driven dirigible in Canada was by C. K. Hamilton in Montreal in 1906. The British airship R100 visited Canada in August 1930. It flew over Montreal and Toronto. A special tower was built just for this visit. After the R101 airship crashed, British airships stopped crossing the ocean. The tower was taken down in 1938.

Sometimes, lighter-than-air vehicles are suggested for use in remote northern areas. They are thought to be cheaper to operate than regular planes. While vehicles like Skyhook and Zeppelin NT get attention, no company has started commercial cargo flights by airship in Canada yet.

First Plane Experiments and Air Shows

Bell's Flying Experiments

Alexander Graham Bell started the Aerial Experiment Association (AEA) to develop aviation. His wife, Mabel Gardiner Hubbard, paid for it by selling some of her land. AEA member Frederick Walker Baldwin was the first Canadian to fly a plane in 1908, though not in Canada.

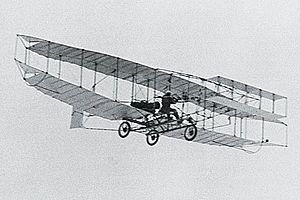

The first powered flight in Canada happened on Bras d'Or Lake in Baddeck, Nova Scotia. This was on February 23, 1909. John Alexander Douglas McCurdy flew the AEA Silver Dart for less than 1 kilometer.

In August 1909, McCurdy and Baldwin showed the Silver Dart and the Baddeck No.1 to Canadian military leaders. The Baddeck No.1 was the second plane built in Canada. Both planes were damaged during the demonstrations. The military leaders were not impressed and lost interest in using such aircraft.

McCurdy later made a record-setting flight over water in 1910. He flew from Florida almost to Cuba. A trial flight to carry newspapers from Montreal to Ottawa in 1913 ended in a crash.

Other Early Flyers

Many people in Canada built kites, gliders, and powered planes before World War I. In Montreal in August 1907, Lawrence Lesh made the first heavier-than-air flights in Canada with a glider pulled by another vehicle. These early experimenters faced challenges. They had limited money, and it was hard to find powerful enough engines. Sometimes, they even lacked books explaining how planes worked.

Exciting Air Shows

In 1910, two big "aviation meets" were held in Montreal and Toronto. Several Canadian flying records were set there. In October 1910, at an air show near Belmont, New York, Grace Mackenzie became one of the first Canadian women to fly. She was the daughter of Sir William Mackenzie. Mackenzie soon married her pilot, Count Jacques de Lesseps. De Lesseps Field near Toronto was named after the French pilot. Air shows were common in Canada until the war started. Often, American "barnstormers" (pilots who performed stunts) took part in Canadian events like fairs. Seeing a plane was a big attraction because it was so new. Planes and performers could cross the border easily.

Canada's First Flying Accident

The first person to die in a plane crash in Canada was John Bryant. He was killed in Victoria on August 6, 1913. This was the only flying death before World War I. Bryant was visiting British Columbia from the US with his wife, Alys McKey Bryant. She was also a pilot. Earlier on their trip, Alys became the first woman to pilot a plane in Canada.

World War I and Canadian Pilots

More than 23,000 Canadians served in British air forces during the First World War. These included the Royal Flying Corps, Royal Naval Air Service, and later the Royal Air Force. Over 1,500 Canadians were killed. Famous Canadian pilots include Billy Bishop, William George Barker, and Alan Arnett McLeod. They all received the Victoria Cross, a very high award for bravery. More than 180 Canadian pilots became "aces," meaning they shot down five or more enemy planes. Canadian aircrew served in all war zones. They fought in air battles, dropped bombs, took air photos, and helped direct artillery.

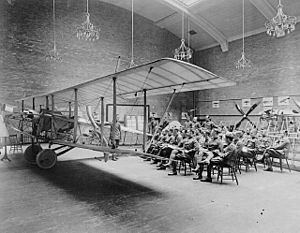

In 1915, the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company from New York opened a small factory in Toronto. It built the JN-4 training aircraft. McCurdy managed this factory. The Curtiss factory built 20 planes with pontoon floats for landing on water. These were sold to Spain, making them the first Canadian-built planes exported. The Canadian government soon bought the company and called it Canadian Aeroplanes Ltd.. The Curtiss factory also had a flying school, which trained 129 pilots. By the end of World War I, the factory had built 2,900 aircraft. This included 1,000 JN4s, built in just three months and sent to the United States for pilot training. Plane building stopped when the war ended.

Even with many Canadians flying in the military, the Canadian government showed little interest in having its own air force. Canadian politicians did not try to pay for flight training, buy planes, or build airfields. The Canadian Aviation Corps was started in 1914 by Sir Sam Hughes. It had only three members and was not successful. It never flew in combat, and its only plane was abandoned after a few months. A Canadian Air Force was created in 1918 but was soon shut down after the war. A permanent air force was not created until 1920. Canadians wanting flight training usually had to join French or British air forces. Some went to schools in Toronto and Vancouver, or got training when the RAF set up schools in Canada in 1917.

Very little civilian flying happened during the war. However, American pilot Katherine Stinson gave shows. She even delivered air mail between Calgary and Edmonton. In eastern Canada, shows by Ruth Law included races against cars.

Between the World Wars

After World War I, Britain gave Canada over 100 extra planes. These included planes that landed on land and water. The United States also gave several extra Curtiss HS flying boats. These had been used to hunt submarines. The donated planes were used by the new air force and for civilian jobs. These jobs included spotting forest fires, taking aerial photos, and exploring. Seaplanes could use lakes and rivers instead of runways. This made them perfect for exploring and patrolling remote areas.

Many Canadians had learned to fly during the war, and there were plenty of extra planes. A two-year boom in aviation followed. The first flight with a paying passenger in Canada happened in 1920. It was between Winnipeg and The Pas. The total number of aviation companies, planes, and pilots then went down between 1920 and 1924. However, the amount of freight carried by air greatly increased. Canadian aviation was slowly changing from an experimental time to a commercial one.

Plane manufacturing started again in 1923. Canadian Vickers got a contract to build eight flying boats for the new air force. De Havilland of England started building "Moth" planes in 1927. The Noorduyn company, founded in 1933, made the Noorduyn Norseman. This plane was used for bush flying all over Canada. The US Army Air Force used this type during World War II, and many were built. War-surplus planes were replaced by types made specifically for civilian use. By the 1930s, enclosed cabins made pilots and passengers much more comfortable.

Mail had been carried by air in various demonstrations in the early 1920s. But it wasn't until 1927 that the Post Office started regular air mail service.

Rules for Flying and a New Air Force

The Canadian Air Board was created in 1919. It controlled all civilian and military flying. In 1923, it joined the Department of National Defence (DND). The Aeronautics Act of 1919 gave the government power to make rules for flying.

When the Air Board joined the DND in 1923, the Canadian Air Force took over. This air force was not permanent. It had been formed in 1920 to give pilots refresher training. It became responsible for all civilian and military flying. The CAF became "Royal" in 1924. It continued with civilian flying and control until 1926. That year, the Directorate of Civil Government Air Operations (CGAO) took over all non-military aviation rules. In 1936, the Canadian Privy Council decided that flying was under federal control. This allowed the Department of Transport (the new name for CGAO) to become the civil authority over aviation in 1936. It took over from the Department of National Defence.

In the late 1930s, the Royal Canadian Air Force focused on becoming a stronger military group.

Building the Airway System

By 1927, a plan was made for a system of airways across the country. The idea was to have a major airport every 100 miles. Emergency landing strips would be every thirty miles across Canada. Airfields had lights for navigation and runways. Navigation beacons were also set up. During the Great Depression, starting in 1932, many unemployed men were put to work. They cleared air strips using hand tools and horse-drawn machines. This helped provide some jobs. By 1937, the airway system stretched from Vancouver to Sydney, a distance of 3,108 miles.

In 1928, the Dominion Meteorological Service started giving weather forecasts for aviation. But this stopped in 1932 because the government cut spending during the Depression. When Trans-Canada Air Lines started in 1936, aviation weather forecasts were provided again. Forecasting stations were in Moncton, Toronto, Kapuskasing, Winnipeg, Lethbridge, and Vancouver. There were also smaller weather stations in between. Later in the 1930s, plans were made for an airway system to reach from Edmonton into the far North.

Starting Civilian Airlines

The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) asked to start air service in 1919. But it didn't get involved in aviation at first. By 1930, Canada was one of the few countries without a national airline.

In Western Canada, Western Canadian Airways was founded in 1926 by James Richardson. This airline specialized in flying in the North. It was known for airlifting materials and men for surveying the port of Churchill in 1927. After buying some other airlines, it was renamed Canadian Airways in 1930. Cherry Red Airline was founded in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan in 1928 for similar purposes.

The Great Depression hit the Canadian civil aviation industry hard. The government did not want to spend money on aviation when the economy was bad. R.B. Bennett famously said he didn't want government-funded planes flying over farmers whose fields were blowing away. Government air mail contracts were canceled. This caused financial problems for small aviation companies that relied on mail. Jobs like air photography, transporting police to northern posts, and air mail were briefly done by private companies. But then the RCAF took them over. This made it easier for the government to keep funding the RCAF.

The Canadian government did not have a national plan for developing civilian aviation. The Air Force and Government Civil Air Operations competed directly with private companies. The Post Office only wanted the cheapest air mail service. Because of this, civilian aviation grew slowly and without a clear plan. Without a national trans-Canada airline, U.S. airlines got important routes across the border. The British Imperial Airways had no Canadian airline to work with for trans-Atlantic routes. So, routes served by the U.S. Pan Am were used for traffic from Atlantic flights. Without reliable air mail contracts, private aviation companies could not make enough money. Without proper air facilities, freight, mail, and passengers were carried by foreign airlines instead of Canadian ones. Much of this delay was because Andrew McNaughton was head of the Department of National Defence. He protected Air Force operations, which hurt the development of civilian airlines.

C. D. Howe was very important in starting Trans-Canada Air Lines (TCA) in 1937. Like the railways before it, TCA was founded as the national cross-continent airline. This was to keep out foreign competitors. It was made a part of CNR. See main article Air Canada#History.

CPR was a part owner in Canadian Airways. By 1941, CPR bought Canadian Airways and other regional airlines. It formed Canadian Pacific Air Lines in 1942. TCA, the government-controlled airline, was named the official transcontinental and international carrier in 1943. For almost 40 years, TCA and Air Canada benefited from government rules on air routes, fares, and service. Government rules were thought to be needed to stop harmful competition between TCA and Canadian Airways. The two airlines, TCA and Canadian Airlines/CP Air, remained strong rivals for the rest of the 20th century.

Taking Pictures from the Air

Aerial photography was an important job for mapping remote parts of Canada. Extra planes given to Canada by the British and U.S. governments, or bought by new private aviation companies, were used for air surveys and photography. During the period between the wars, the RCAF did a lot of air mapping. Mapping remote regions from the air was helpful for developing forests and mines in Canada's North. The experience gained during this time helped build the Commonwealth Air Training Program during World War II.

International Flying

Commercial civilian flying grew a lot worldwide after World War I. Many European countries started national airlines. These were often supported by the government. They did this for national pride, safety, and trade. Examples include Sabena, KLM, Deutsche Luft Hansa, and Air France. The United Kingdom started Imperial Airways. Its goal was to connect the far-off parts of the British Empire. It provided air mail and passenger services for British and allied territories overseas. In the United States, there was a large land area, one language, a growing population, and good flying conditions. These factors helped private airlines grow quickly. Many regional airlines grew and wanted to expand to Canada and Latin America. In the United States, Pan American World Airways became almost the unofficial national airline. It received special support from the American government in talks with other countries.

Conditions in Canada were different from Europe and the U.S. Flying between cities was not the most important type of aviation in the 1920s. Float planes, flying on northern lakes and rivers, became the basis for much commercial flying. They helped with mining, the paper industry, medical services, police, and mail. So, many private companies formed regional airlines to serve this business. Little money was needed to build fixed runways for floatplane operations. The only government help available was contracts to carry air mail. However, when the Great Depression started, even these mail contracts were canceled. This pushed some airlines close to bankruptcy. While Imperial Airways talked with Pan Am about the profitable trans-Atlantic route, Canadian interests were at risk. A trans-Atlantic route that skipped Canadian territory would greatly slow down commercial aviation development in Canada. No national airline existed, and none of the regional airlines could negotiate with Imperial Airways for trans-Atlantic routes. One possible route, using the planes of that time, would go from New York to Newfoundland to Ireland to London. This would completely bypass Canadian territory.

International aviation agreements were made, mostly among European countries, after World War I. The Air Navigation Convention, signed by European countries in 1920, tried to set international rules for air traffic. Canada was not strongly represented in these talks. But it did get a change to one article that would let Canada and the U.S. make their own agreements on cross-border air rules. However, the United States Senate never approved the convention, so the Americans never joined it.

One result of Canada's involvement in international air rules was the setting up of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) headquarters in Montreal.

Flying Across Canada

Although Alcock and Brown had flown over the North Atlantic in 1919, the first non-stop flight across Canada (from Halifax to Vancouver) didn't happen until 1949. A cross-Canada air mail demonstration by the Canadian Air Force was done in 1920. But this was a relay using about six planes. American pilot James Dalzell McKee (1893–1927) and RCAF Squadron Leader Earl Godfrey took nine days in September 1926 to fly from Montreal to Vancouver. McKee gave money for the Trans-Canada Trophy in 1927 to recognize achievements in Canadian aviation. McKee was killed in a floatplane crash.

Opening Up the North

A plane could cross and photograph rough, undeveloped country in hours. This would take weeks to cross by canoe, dog team, horseback, or on foot. Resource companies did well because they could move people and materials all year. Winter flying was especially important. It was so cold that oil had to be drained from engines and kept inside overnight. Then it was preheated and poured back in. Skis and floats were as useful as wheels for northern flyers. These flights were made in very basic conditions. Often, there were no prepared airfields, no reliable weather forecasts, no radio or visual navigation aids, poor maps, and often no indoor places for repairs. Today, the Canadian Bushplane Heritage Centre museum tells some of the key stories from this time.

Bush flying in Canada started right after the First World War. It used extra planes from the war for aerial photography and spotting forest fires. The Ontario Provincial Air Service used planes to watch for forest fires and carry firefighters. They also developed the water bomber for fighting fires. The bush pilot era produced famous pilots like Wop May and Punch Dickins. In January 1929, Wop May's flight from Edmonton to Fort Vermilion, Alberta carrying diphtheria vaccine became big news. Both May and Dickins, along with many other bushplane pilots, started Canadian aviation businesses.

Fred J. Stevenson performed air stunts after the war. He flew in Manitoba and Northern Ontario. In 1927, he joined Richardson's Western Canada Airways. He airlifted 14 men and 17,000 pounds (7,700 kg) of material to help with exploration at Fort Churchill. These flights proved how useful planes were in the North. He was killed in a plane crash.

World War II and Aviation Growth

The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan in Canada trained over 130,000 aircrew during the Second World War. Some of the facilities built for this program were used after the war to expand and improve civilian aviation.

Canadian factories, far from enemy attacks, built both training and combat planes. Since delivering planes by ship was slow and risky, complete aircraft were flown in stages across a North Atlantic route to Europe. Canadian Pacific Air Lines first organized these flights. The RAF later took over this service, calling it RAF Ferry Command. About 9,000 planes were sent this way. The experience gained became the basis for regular trans-Atlantic flights after the war. The airport established at Gander, Newfoundland was a key part of the North Atlantic route and is still used today.

The first women pilots were not licensed in Canada until 1928. As more men went to fight, women were increasingly hired for aviation technical support and plane manufacturing. Ferry Command and the British Air Transport Auxiliary used Canadian female pilots to move fighter and bomber planes across the Atlantic.

In the West, the North West Staging Route was used to send warplanes from factories in the United States to the Soviet Union. Starting in 1940, fifteen air bases and many emergency landing strips were prepared. They stretched from Great Falls, Montana, through Western Canada to Alaska. The planes were finished with Soviet markings, prepared for winter, and flown in stages to Alaska. There, Soviet crews would take over the planes and fly them through Siberia to war zones. About 5,000 fighters and 1,300 bombers and transport planes were sent to the Soviet Union this way. Also, 700 planes were sent for air defense of Alaska against a threat from Japan. Many internal communication, supply, and search-and-rescue flights also used this air route.

Civilian flying during the war was limited. Priority was given to travel for war business, and oil and gasoline were rationed. However, northern bush plane operations continued to support mining. This included exporting uranium concentrate for the atomic bomb project.

Making Planes in Canada

The Curtiss company set up a factory to build engines and plane parts in 1915. The federal government took this over and operated it as Victory Aircraft until 1945. Then, it was sold to Hawker Siddeley.

Many planes made in Canada during the Second World War were designs licensed from British or American companies. Sometimes, they were changed to fit available materials, engines, and production facilities.

During World War II, companies like Canadian Car and Foundry, which normally didn't make planes, used their factories to build fighters and bombers. About 16,000 aircraft were made in Canada. This included about 450 four-engine Avro Lancaster bombers and 1,400 Hawker Hurricane fighters. Many training planes were also built, such as the Harvard, Anson, and Tiger Moth.

Some aviation manufacturers in Canada included:

- Canadian Vickers (1923-1944)

- Fairchild Aircraft Ltd. (1920-1950)

- Fleet Aircraft (1928-1957)

- Canadair (1944-1986)

- Bristol Aerospace (1930-1996, started as McDonald Brothers)

- Avro Canada (1945-1962)

- de Havilland Canada (1928-1986)

- Viking Air (1970–present)

- Bombardier Aerospace (1986–present, bought parts of Canadair, later added Short Brothers, Lear, and de Havilland Canada)

- Magellan Aerospace (1996–present)

Helicopters in Canada

The first helicopter-like aircraft registered in Canada was a Pitcairn PCA-2 gyroplane in 1931. Another Pitcairn gyroplane model, PAA-1, was registered in 1932. For about 20 years, it was used for various jobs. These included air shows, spraying farms and forests, and photography. Helicopters interested Canadian amateur builders in the 1930s (like the Froebe helicopter). But no commercial development followed.

During World War II, the Sikorsky R-4 was mass-produced. Units were used by the U.S. Navy, U.S. Coast Guard, and British Royal Navy. Seven Canadians were trained on the R-4. Military uses for the helicopter included fighting submarines and search and rescue. On May 11, 1945, Canadian R-4 pilot Lt. Cdr. Dennis Foley helped successfully rescue a downed Corsair pilot.

A helicopter was used in 1944 in a search and rescue operation on the St. Lawrence River. An American Sikorsky R-4 was sent for the search, but survivors were rescued by an icebreaker. In 1945, another U.S. R-4 was sent to transport survivors of a Canso crash in Labrador. U.S. Coast Guard helicopters were again called for rescue service in September 1946. They rescued survivors of a crashed Sabena DC-4 that hit the ground near Gander airport.

The RCAF got its first helicopter, a Sikorsky S-51, in 1947. More helicopters were bought by the RCAF and RCN (Royal Canadian Navy) and used for search and rescue. Many flights were made during the 1950 Red River flood to carry passengers and take air photos. In 1955, helicopters from the RCAF No. 108 squadron helped build the Mid Canada Line of radar stations.

Cold War Era and Jet Planes

During the 1950s and 1960s, the United States thought Soviet planes flying over the Arctic were a threat. They spent a lot of effort and money on defense systems. Early-warning radar stations for the DEW line and Pinetree Line were built partly in the Canadian North. Building these stations required many air freight shipments to isolated areas. Also, anti-aircraft missiles called BOMARC were placed in Canada. These were very controversial because they could carry nuclear bombs.

Around 1953, Canada started developing its own supersonic interceptor plane, the Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow. The test plane flew faster than sound in 1958. But the type of threat changed from manned planes over the North Pole to ballistic missiles. Many interceptor plane programs of that time were canceled. Canada and the United States had signed a joint NORAD treaty in 1958. The BOMARC system was thought to handle the bomber threat. Since there were no export sales, the government decided the defense budget could not pay for both missile operations and plane development. So, the Arrow program was canceled in early 1959. The loss of the Arrow project led to the closing of Avro Canada and many aerospace workers losing their jobs.

In 1978, Judy Cameron became the first female pilot hired to fly for a major Canadian airline (Air Canada).

Airline Rules and Changes

Passenger airlines in Canada were closely regulated from the 1930s until the late 1970s. Rules controlled which companies could be regional or national carriers. The government approved routes, schedules, and fares. Trans-Canada Airlines was given special treatment for routes and international flights. Deregulation of airlines in the United States, along with requests by CP Air and Wardair to provide national service, led to changes in the rules. These included the "Air Canada Act" of 1977. This act made the national airline a Crown corporation, competing almost equally with other Canadian airlines. By 1988, Air Canada became fully private.

The National Airports Policy of 1994 gave control of 90 airports to local organizations. Also, air navigation services were sold in 1996 to Nav Canada, a private organization.

100 Years of Flight Celebration

In 2009, there were many celebrations for the 100th anniversary of powered flight in Canada. As part of this, the Canadian military painted the 2009 Demonstration McDonnell Douglas CF-18 Hornet in a special dark blue and gold design. It included the names of the 100 most important people in Canadian aviation history.

See also

- Air Canada

- Avro Canada C102 Jetliner

- Avro Canada CF-100 Canuck

- Bombardier Aerospace and Embraer S.A. government subsidy controversy

- Canada's Aviation Hall of Fame

- Canadian Airlines

- List of defunct airlines of Canada

- List of defunct airports in Canada

- Operation Yellow Ribbon

- Pacific Western Airlines

- Transair (Canada)

- Western Canada Aviation Museum

- Ontario Provincial Air Service

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |