Hundred Years' War, 1345–1347 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hundred Years' War 1345–1347 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hundred Years' War | |||||||

The English assault on Caen, from Froissart's Chronicles |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Kingdom of England | Kingdom of France | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| King Philip VI (WIA) John, Duke of Normandy |

|||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown, light | Unknown, heavy | ||||||

From 1345 to 1347, England launched attacks during the Hundred Years' War. These attacks led to many French defeats. A lot of French land was lost or destroyed. The English also captured the important port of Calais. The war had started in 1337. It became more intense in 1340 when England's King Edward III claimed the French crown. He then fought in northern France. After that, there was a quiet period in the main fighting, but small battles continued.

In early 1345, King Edward decided to restart the full war. He sent a small army to Gascony in southwest France. This army was led by Henry, Earl of Derby. King Edward himself led the main English army to northern France. Edward's army faced delays and a storm scattered his ships. Despite this, his attack was very successful. The next spring, a large French army, led by the French prince John, Duke of Normandy, attacked Derby's forces.

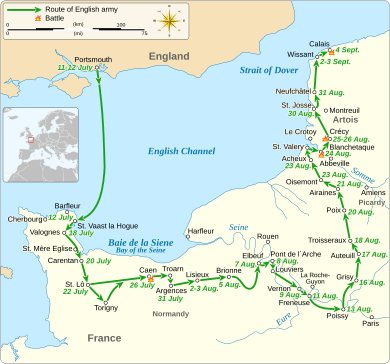

Edward reacted by landing an army of 10,000 soldiers in northern Normandy. The English army caused a lot of damage in Normandy. They attacked and took the city of Caen, causing many deaths. They then moved along the Seine River, getting within 20 miles (32 km) of Paris. The English army then turned north. They heavily defeated a French army led by King Philip VI at the Battle of Crécy on August 26, 1346. After this victory, they quickly began to surround Calais. The time from Derby's win near Bergerac in August 1345 to the start of the Calais siege in September 1346 was called Edward III's annus mirabilis, meaning "year of marvels."

The siege of Calais lasted eleven months. It used up a lot of money and soldiers for both countries. Finally, the town fell to the English. Soon after, the Truce of Calais was agreed upon. This was a peace agreement that lasted for nine months, until July 7, 1348. It was extended many times until 1355. The Hundred Years' War finally ended in 1453. By then, the English had lost all French land except Calais. Calais remained an English trading post in northern France for over 200 years.

Contents

Why the War Started

Since the Norman Conquest in 1066, English kings had owned land in France. They inherited these lands. Owning French land meant they were vassals, or loyal subjects, of the French kings. The English king's French lands were a big reason for conflict between the two kingdoms throughout the Middle Ages. French kings always tried to stop English power from growing. They took back lands whenever they could. Over time, English lands in France got smaller. By 1337, only Gascony in southwest France and Ponthieu in northern France were left. The people of Gascony preferred being linked to a distant English king who left them alone. They did not like a French king who would interfere in their lives.

After several disagreements between Philip VI of France (who ruled from 1328 to 1350) and Edward III of England (who ruled from 1327 to 1377), a big decision was made. On May 24, 1337, Philip's Great Council in Paris decided to take back Gascony and Ponthieu. They said Edward had broken his promises as a loyal subject. This event started the Hundred Years' War, which lasted for 116 years.

Even though Gascony caused the war, Edward could not send many resources there. For the first eight years of the war, whenever an English army fought in France, it was in northern France. In 1340, Edward officially claimed the French throne. He said he was the closest male relative of Philip's last family member, Charles IV. He then led a costly campaign against Tournai that didn't achieve much. After this, there was a quieter period in the fighting, made official by the Truce of Espléchin that same year.

War Plans for 1345

In early 1345, Edward decided to restart the full war. He planned to attack France from three sides. William, Earl of Northampton, would lead a small group to Brittany. A slightly larger group would go to Gascony under Henry, Earl of Derby. The main army would go with Edward to either northern France or Flanders. The previous governor of Gascony, Nicholas de la Beche, was replaced by Ralph, Earl of Stafford. Stafford sailed to Gascony in February with an early force.

French spies found out about the English plan to attack in three areas. But France did not have enough money to raise a big army for each area. The French correctly guessed that the English would focus their main effort in northern France. So, they sent what resources they had there. They planned to gather their main army at Arras by July 22. People in southwest France were told to rely on their own forces. However, because the Truce of Malestroit was still in effect, local lords did not want to spend money, so little was done.

Events of 1345

Edward's main army sailed on June 29. They stayed anchored off Sluys in Flanders until July 22 while Edward handled diplomatic matters. When they finally sailed, probably aiming for Normandy, a storm scattered them. They found their way back to English ports over the next week. After more than five weeks on ships, the soldiers and horses had to get off. There was another week's delay while the King and his council discussed what to do. By then, it was too late to do anything with this army before winter. Knowing this, Philip sent more soldiers to Brittany and Gascony. Peter, Duke of Bourbon was put in charge of the southwest front on August 8.

Gascony Campaign

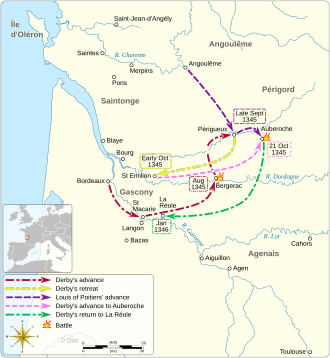

Red arrows – Derby's advance to Bergerac and Périgueux

Orange arrow – Derby's withdrawal

Blue arrows – Louis of Poitiers' advance to Périgueux and Auberoche

Pink arrow – Derby's return to Auberoche

Green arrow – Derby's move back to Gascony and La Réole

Derby's force left Southampton at the end of May 1345. Bad weather forced his fleet of 151 ships to stop in Falmouth for several weeks. They finally left on July 23. The Gascons, who had been told by Stafford to expect Derby in late May, saw that the French were weak. They started fighting without him. The Gascons captured the large castles of Montravel and Monbreton on the Dordogne in early June. Both were taken by surprise. Their capture broke the fragile Truce of Malestroit. Stafford then marched north to besiege Blaye. He left the Gascons to continue this siege and went to Langon, south of Bordeaux, to start a second siege. The French quickly called for more soldiers.

Meanwhile, small groups of Gascons raided across the region. Local French groups joined them, and some minor nobles sided with the Anglo-Gascons. They had some successes. Their main effect was to keep most of the French soldiers busy in the region. This made the French call for more soldiers, but none came. Large areas were left without defense.

On August 9, Derby arrived in Bordeaux. He had 500 men-at-arms, 1,500 English and Welsh archers (500 of them on ponies for speed), and support troops like 24 miners. Most of them were experienced soldiers. After two weeks of gathering more men, Derby decided to change his plan. Instead of continuing to besiege towns, he decided to attack the French directly before they could gather their forces. The French in the region were led by Bertrand de l'Isle-Jourdain. He was gathering his forces at Bergerac, an important town for communication and strategy. Bergerac was 60 miles (97 km) east of Bordeaux and controlled a key bridge over the Dordogne River.

Derby's Attack

Derby moved quickly and surprised the French army in late August 1345. He ambushed their cavalry outside Bergerac. Then he pushed their panicked foot soldiers back to the town. The French suffered many losses, with many killed and a large number captured, including their commander. The remaining French soldiers gathered around John, Count of Armagnac, and retreated north to Périgueux, the capital of the area. Within days of the battle, Bergerac fell to an Anglo-Gascon attack and was then looted. After getting organized for two weeks, Derby left a large group of soldiers in the town and moved north to Périgueux, taking several strongholds along the way.

During September, John, Duke of Normandy, the son of King Philip VI, gathered an army of more than 20,000 men. He moved his forces around the area. In early October, a very large group of French soldiers pushed back Derby's force, which retreated towards Bordeaux. With more soldiers, the French began to besiege the English-held strongholds. A French force of 7,000, led by Louis of Poitiers, besieged the castle of Auberoche, 9 miles (14 km) east of Périgueux. After a night march, Derby attacked the French camp on October 21 while they were eating. He took them by surprise, causing many early losses. The French fought back, and there was a long, hand-to-hand battle. It ended when the small English group inside the castle made a sortie (sudden attack) and hit the French from behind. The French broke and ran away. Historians describe French losses as "terrible" and "extremely high." Many French nobles were captured. Lower-ranking soldiers were usually killed on the spot. The French commander, Louis of Poitiers, died from his wounds. Captured prisoners included l'Isle-Jourdain, the second in command, two counts, seven viscounts, three barons, two seneschals (governors), a nephew of the Pope, and so many knights that they were not counted.

This four-month campaign is called "the first successful land campaign" of the Hundred Years' War. It had started more than eight years earlier. Modern historians have praised Derby's leadership in this campaign. They called him a "superb and innovative tactician" and said his actions were "brilliant in the extreme." A writer from 50 years later called him "one of the best warriors in the world."

Events of 1346

Siege of Aiguillon

For the 1346 fighting season, Duke John was again put in charge of all French forces in southwest France. In March, a French army of 15,000 to 20,000 soldiers, much larger than any Anglo-Gascon force, marched on the English-held town of Aiguillon. They began to besiege it on April 1. On April 2, an arrière-ban, a formal call for all able-bodied men to join the army, was announced for southern France. French money, supplies, and manpower were all focused on this attack.

Crécy Campaign

During the first six months of 1346, Edward again gathered a large army in England. The French knew about this. But it was very hard to land an army anywhere except a port. The English no longer had a port in Flanders, but they had friendly ports in Brittany and Gascony. So, the French thought Edward would sail to one of those places, probably Gascony, to help Aiguillon. To protect against any English landing in northern France, Philip VI relied on his strong navy. This trust was misplaced because his navy gathered late and could not effectively patrol the whole Channel. Edward's army boarded the largest fleet ever assembled by the English up to that time, 747 ships. The French could not stop Edward from crossing the Channel and landing at St. Vaast la Hogue on July 12. This was 20 miles (32 km) from Cherbourg in northern Normandy. The English army had about 10,000 soldiers and achieved complete strategic surprise. Philip called his main army, under Duke John, back from Gascony. After a fierce argument with his advisors, John refused to move until his honor was satisfied by the fall of Aiguillon.

Edward's goal was to conduct a chevauchée, which was a large-scale raid across French land. This was meant to lower his opponent's morale and wealth by burning towns and stealing valuables. His army marched south through the Cotentin peninsula. They caused a lot of destruction through some of the richest lands in France, burning every town they passed. The English fleet sailed alongside the army. Landing parties destroyed the country up to 5 miles (8 km) inland, taking huge amounts of loot. After their ships were full, many crews left. The fleet also captured or burned more than 100 French ships; 61 of these had been turned into warships. Caen, a major city in northwest Normandy, was attacked on July 26.

On July 29, Philip called for an arrière-ban (a general call to arms) for northern France at Rouen. The English army marched out of Caen towards the River Seine on August 1, arriving on the 7th. Philip again sent orders to John, insisting he stop the siege of Aiguillon and march his army north. Meanwhile, the English destroyed the land up to the suburbs of Rouen. Then they left a path of destruction and violence along the left bank of the Seine to Poissy, 20 miles (32 km) from Paris. They reached Poissy on August 12. On August 14, John tried to arrange a local truce at Aiguillon. Lancaster, as Derby was now known, knew what was happening in the north and in the French camps around Aiguillon, so he refused. On August 20, after five months of siege, the French gave up the operation and marched away quickly and in disorder. On August 16, the English army outside Paris had turned north. They then became trapped in an area where the French had removed all food. They escaped by fighting their way across the Somme River against a French blocking force in the Battle of Blanchetaque on August 24.

Battle of Crécy

Two days later, on August 26, 1346, the English fought the French at the Battle of Crécy. The English chose the battleground. The French army was very large for that time, several times bigger than the English force. The French raised their sacred battle banner, the oriflamme. This meant no prisoners would be taken. There was an initial exchange of arrows, which the English won. They defeated the Italian crossbowmen who were fighting them.

The French then launched cavalry charges with their mounted knights against the English men-at-arms, who had gotten off their horses to fight. These charges were messy because they were unplanned. The French had to push through the fleeing Italians, deal with muddy ground, charge uphill, and avoid pits dug by the English. English archers also fired arrows, causing many losses. By the time the French charges reached the English foot soldiers, they had lost much of their power. A person who lived at the time described the hand-to-hand combat as "deadly, without pity, cruel, and very horrible." The French charges continued into the night, all with the same result: fierce fighting followed by a French defeat. Philip himself was caught in the fighting. Two horses were killed under him, and he was hit by an arrow in the jaw. The oriflamme was captured after its bearer was killed. The French broke and ran away. The English, exhausted, slept where they had fought.

The French suffered very heavy losses. Records from the time say 1,200 knights and over 15,000 other soldiers were killed. The highest estimate for English deaths was 300. Historian Andrew Ayton calls the English victory "unprecedented" and "a devastating military humiliation" for the French. Historian Jonathan Sumption sees it as "a political disaster for the French Crown." The battle was reported to the English Parliament on September 13. It was described in glowing terms as a sign of God's favor and a reason for the huge cost of the war so far.

Siege of Calais

After resting for two days and burying the dead, the English marched north. They continued to destroy the land. They set several towns on fire, including Wissant, the usual port for English ships going to northern France. Outside the burning town, Edward held a meeting. They decided to capture Calais. This was a perfect entrepôt (trading post) for the English. It had a safe harbor and good port facilities. It was also the closest part of France to the ports of southeast England. It was near the border of Flanders, which was part of France but was rebelling. Flanders was allied with the English and willing to send troops to help Edward. The English arrived outside the town on September 4 and began to besiege it.

Calais was strongly fortified. It was surrounded by large marshes, had enough soldiers, and was well-supplied. It could also get more soldiers and supplies by sea. The day after the siege started, English ships arrived offshore. They resupplied, re-equipped, and reinforced the English army. Over time, a major operation brought supplies from all over England and Wales to feed the besiegers. Supplies also came overland from nearby Flanders. Parliament reluctantly agreed to pay for the siege. Edward declared it a matter of honor and said he would stay until the town fell. The period from Derby's victory near Bergerac in August 1345 to the start of the siege of Calais on September 4 became known as Edward III's annus mirabilis (year of marvels).

French Actions

Philip was unsure what to do. On the day the siege of Calais began, he sent most of his army home to save money. He was convinced Edward had finished his raid and would go to Flanders and ship his army home. On or shortly after September 7, Duke John contacted Philip. John had just sent his own army home. On September 9, Philip announced the army would gather again at Compiègne on October 1. This was too short a time. Then they would march to help Calais.

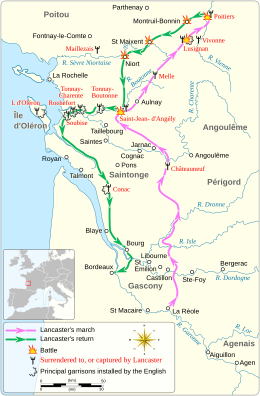

One result of this hesitation was that Lancaster in the southwest could launch attacks into Quercy and the Bazadais. He also led a chevauchée (raid) 160 miles (260 km) north through Saintonge, Aunis, and Poitou. He captured many towns, castles, and smaller fortified places. He also attacked the rich city of Poitiers. These attacks completely broke the French defenses. They moved the fighting from the heart of Gascony to 60 miles (97 km) or more beyond its borders. Few French soldiers had arrived at Compiègne by October 1. As Philip and his court waited for more soldiers, news of Lancaster's conquests arrived. Believing Lancaster was heading for Paris, the French changed the meeting point for any men not already at Compiègne to Orléans. They reinforced these men with some already gathered to block Lancaster. After Lancaster turned south to head back to Gascony, those Frenchmen already at or heading towards Orléans were sent back to Compiègne. French planning fell into chaos.

Even though only 3,000 men-at-arms had gathered at Compiègne, the French treasurer could not pay them. Philip canceled all attack plans on October 27 and sent his army home. There was a lot of blame. Officials at all levels of the French treasury were fired. All financial matters were given to a committee of three senior abbots. The King's council tried to blame each other for the kingdom's problems. Duke John had a falling out with his father and refused to attend court for several months.

Battle of Neville's Cross

Philip had been asking the Scots to invade England since June 1346. This was part of their agreement under the Auld Alliance. The Scottish King, David II, believed that English forces were completely focused on France. So, he agreed on October 7. He was surprised by a smaller English force. This force was made up only of soldiers from the northern English counties. A battle was fought at Neville's Cross outside Durham on October 17. It ended with the Scots being defeated. Their King was captured, and most of their leaders were killed or captured. This battle freed English forces for the war against France. The English border counties could now defend against the remaining Scottish threat using their own resources.

Events of 1347

Calais Falls

During the winter, the French worked hard to strengthen their navy. This included French and mercenary Italian galleys and French merchant ships, many changed for military use. In March and April 1347, more than 1,000 long tons (1,016 metric tons) of supplies were brought into Calais without any resistance. Philip tried to gather his army in late April. But the French ability to gather their army quickly had not improved since the autumn. By July, it still had not fully gathered. In April and May, the French tried and failed to cut off the English supply route to Flanders. At the same time, the English tried and failed to capture Saint-Omer and Lille.

In late April, the English built a fort that allowed them to control the entrance to the harbor. In May, June, and July, the French tried to force supply ships through, but they failed. On June 25, the commander of the Calais soldiers wrote to Philip. He said their food was gone and suggested they might have to eat each other. Despite growing money problems, the English steadily sent more soldiers to their army throughout 1347. They reached a peak strength of 32,000. A force of 20,000 Flemish allies gathered less than a day's march from Calais. These forces were supported by 24,000 sailors, in a total of 853 ships. On July 17, Philip led the French army north to within sight of the town, 6 miles (10 km) away. Their army had between 15,000 and 20,000 soldiers. The English position was clearly too strong to attack, so Philip hesitated. On the night of August 1, the French withdrew. On August 3, 1347, Calais surrendered. The entire French population was forced to leave. A huge amount of valuable goods was found in the town. Edward filled Calais with English people, and a few Flemings. Calais was very important to England's efforts against the French for the rest of the war. It served as an English trading post in northern France for over 200 years. It allowed supplies and equipment to be gathered before a campaign. A ring of strong forts defending the areas around Calais was quickly built. This area became known as the Pale of Calais.

The Truce

As soon as Calais surrendered, Edward paid off most of his army and released his Flemish allies. Philip, in turn, sent the French army home. Edward quickly launched strong raids up to 30 miles (48 km) into French territory. Philip tried to call his army back but faced serious difficulties. His treasury was empty, and taxes for the war had to be collected by force in many places. Despite these urgent needs, ready money was not coming in. The French army had little desire for more fighting. Philip had to threaten to take away the lands of nobles who refused to join the army. He pushed back the date for his army to gather by a month. Edward also had trouble raising money. This was partly because he had not expected to return to large-scale fighting, so his treasury was empty. He used harsh methods to raise money, which were very unpopular. The English also suffered two military setbacks. A large raid was defeated by the French soldiers in Saint-Omer. And a supply convoy on its way to Calais was captured by French raiders from Boulogne.

Two cardinals acting as papal messengers found that both kings were willing to listen to their ideas. On September 28, 1347, a truce, known as the Truce of Calais, was officially agreed upon. This truce was thought to favor the English the most. During its time, the English were confirmed to keep their large land gains in France and Scotland. The Flemish were confirmed in their independence. And Philip was stopped from punishing French nobles who had worked against him or even fought him. It lasted for nine months until July 7, 1348, but was extended many times over the years.

What Happened Next

In 1355, the truce was officially ended, and full-scale war started again. In 1360, the part of the war led by Edward ended with the Treaty of Brétigny. By this treaty, huge areas of France were given to England, including the Pale of Calais. In 1369, large-scale fighting broke out again. The Hundred Years' War did not end until 1453. By that time, England had lost all its land in France except Calais. Calais was finally lost after the siege of the town in 1558.

|

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |