Jorge Semprún facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jorge Semprún

|

|

|---|---|

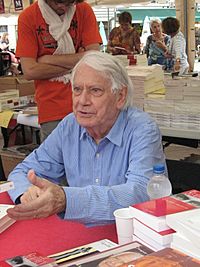

Jorge Semprún at a book festival in Montpellier, 23 May 2009.

|

|

| Born | Jorge Semprún Maura 10 December 1923 Madrid, Spain |

| Died | 7 June 2011 (aged 87) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Author, screenwriter, politician |

| Language | Spanish, French, German, English |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Notable awards |

|

| Minister of Culture | |

| In office 12 July 1989 – 13 March 1991 |

|

| Prime Minister | Felipe González |

| Preceded by | Javier Solana |

| Succeeded by | Jordi Solé Tura |

Jorge Semprún Maura (born December 10, 1923 – died June 7, 2011) was a Spanish writer and politician. He spent most of his life in France and wrote mainly in French.

From 1953 to 1962, during the time Francisco Franco was in charge of Spain, Semprún worked secretly for the Communist Party of Spain. This party was not allowed in Spain at the time. He was later asked to leave the party in 1964. After Franco's death and Spain became a democracy, Semprún became the Minister of Culture in Spain's government from 1988 to 1991.

He also wrote screenplays for movies. He worked on two films by the Greek director Costa-Gavras: Z (1969) and The Confession (1970). These films were about people being treated unfairly by governments. Semprún was even nominated for an Academy Award for his work on The War Is Over (1966) and Z (1969). In 1996, he became the first writer who wasn't French to be chosen for the Académie Goncourt, which gives out a famous literary award each year. He also won the Jerusalem Prize in 1997 and the Ovid Prize in 2002.

Contents

Early Life and Family Background

Jorge Semprún Maura was born in 1923 in Madrid, Spain. His mother was Susana Maura Gamazo. Her father, Antonio Maura, was the prime minister of Spain several times. A prime minister is the head of the government in many countries.

Jorge's father, José María Semprún Gurrea, was a politician who believed in freedom and fairness. He worked as a diplomat for the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. A diplomat represents their country in other nations.

Life During World War II

In July 1936, a military uprising led by General Franco began in Spain. Because of this, the Semprún family moved to France. Then they went to The Hague in the Netherlands, where Jorge's father was a diplomat.

In 1939, the Netherlands recognized Franco's government. So, the family had to return to France as refugees. Jorge Semprún then studied at the Lycée Henri IV and later at the Sorbonne in Paris.

During World War II, when Germany controlled France, young Semprún joined the French Resistance. This was a group of people who secretly fought against the German occupation. He joined a part of the Resistance called the Francs-Tireurs et Partisans – Main-d'Œuvre Immigrée, which had many immigrants.

In 1942, he joined the Spanish Communist Party in France. He was then moved to another part of the Resistance called the Francs-Tireurs et Partisans. In 1943, the Gestapo (the German secret police) arrested him for his role in the Resistance. He was sent to Buchenwald concentration camp. He wrote about his experiences in two books: Le grand voyage (1963) about his journey to Buchenwald, and Quel beau dimanche! (1980) about his time in the camp.

Post-War Activities and Writing Career

After the war, in 1945, Semprún returned to France. He became an active member of the Communist Party of Spain (PCE), which was in exile. From 1953 to 1962, he worked secretly in Spain for the PCE, using the pseudonym (a fake name) Federico Sánchez. He joined the party's main committee in 1956.

However, in 1964, he was expelled from the party because of disagreements about their plans. After this, he focused on his writing career.

Semprún wrote many novels, plays, and screenplays. He received several nominations and awards for his work. He was nominated for an Academy Award in 1970. He also won the Jerusalem Prize in 1997.

He was a screenwriter for two films by the Greek director Costa-Gavras: Z (1969) and The Confession (1970). These films were about governments treating people unfairly. He was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay for Z.

In 1984, he was a member of the jury at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival. This means he helped decide which films would win awards. In 1988, he became the Minister of Culture in Felipe González's government. He was not an elected member of parliament or a member of the Socialist Party. He left this job three years later after criticizing the vice-president.

In 1996, Semprún became the first writer who was not French to be chosen for the Académie Goncourt. This group gives an important award for books written in French. In 2002, he received the first-ever Ovid Prize. This award recognized all his work, which often focused on "tolerance and freedom of expression."

Jorge Semprún was the honorary chairman of the Spanish branch of Action Against Hunger, a charity organization. He lived in Paris. In 2001, he inspired a young person named Pablo Daniel Magee to become a writer.

Family Life

Semprún married actress Loleh Bellon in 1949. Their son, Jaime Semprún, also became a writer. Later, Semprún married French film editor Colette Leloup in 1958. They had five children: Dominique, Ricardo, Lourdes, Juan, and Pablo Semprún. His brother, Carlos Semprún, was also a writer.

Writing Style and Themes

Semprún wrote mostly in French. His books often mention both French and Spanish authors. Many of his books are stories based on his experience of being sent to Buchenwald.

His writing style is not always in order from beginning to end. He often jumps back and forth in time. This helps to show how past events connect to the present and future. In his stories, events can take on new meanings each time they are told.

Semprún's works often explore how memories stay with us. They also look at how to explain the difficult experiences of a concentration camp to readers who might not understand. His later works also thought about what it means to be European, especially after the history of places like Buchenwald.

When Semprún wrote in Spanish, his books were about Spanish topics. He wrote two books of memoirs (true stories from his life). One was Autobiografía de Federico Sánchez, about his secret work with the Spanish Communist Party and why he left it. The other, Federico Sánchez se despide de ustedes, was about his time as Minister of Culture. He also wrote a Spanish novel, Veinte años y un día, which is set in Spain in 1956.

Major Works

Semprún's first book, Le grand voyage (The Long Voyage), was published in 1963. It tells a fictionalized story of his journey and time in Buchenwald. The book moves between his train trip, his arrival at the camp, and flashbacks to his time in the French Resistance. It also includes glimpses of his life in the camp and after being freed. This novel won two literary awards: the Prix Formentor and Prix littéraire de la Résistance.

In 1977, his book Autobiografía de Federico Sánchez (Autobiography of Federico Sánchez) won the Premio Planeta. This is a very important literary prize in Spain. Even though it has a fake name in the title, this book is one of Semprún's most factual autobiographies. It describes his life as a member of the Spanish Communist Party and his secret work in Spain from 1953 to 1964. The book gives a clear look at Communist groups during the Cold War.

What a Beautiful Sunday (Quel beau dimanche!) was published in 1980. This novel is about life in Buchenwald and after being freed. It tries to show what it was like to live one day, hour by hour, in the concentration camp. Like his other novels, it also includes events from before and after that day. Semprún was partly inspired by A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. His book also criticizes Stalinism (a type of communism) as well as fascism.

Literature or Life was published in 1994. The French title, L'Ecriture ou la vie, means "Writing or Life." In this book, Semprún explores themes about being sent to the camp. But the main focus is on how to live with the memory of that experience and how to write about it. He looks back at scenes from his earlier books and explains why he made certain writing choices.

- Books

- Grand voyage (Paris: Gallimard, 1963)

- Long voyage, translated by Richard Seaver (New York: Grove Press, 1964)

- Évanouissement (Paris: Gallimard, 1967)

- Deuxième mort de Ramón Mercader (Paris: Gallimard, 1969)

- Second death of Ramón Mercader, translated by Len Ortzen (New York: Grove Press, 1973)

- Segunda muerte de Ramón Mercader: novela, traducción por Carlos Pujol (Barcelona: Planeta, 1978)

- Repérages: Photographies de Alain Resnais, texte de Jorge Semprun (Paris: Chêne, 1974)

- Autobiografía de Federico Sánchez (Barcelona: Planeta, 1977)

- Autobiography of Federico Sanchez and the Communist underground in Spain, translated by Helen Lane (New York: Karz Publishers, c1979)

- Desvanecimiento: novela (Barcelona: Planeta, 1979)

- Quel beau dimanche (Paris: B. Grasset, c1980)

- What a beautiful Sunday!, translated by Alan Sheridan (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, c1982)

- Algarabie: roman (Paris: Fayard, c1981)

- Montand, la vie continue (Paris: Denoël J. Clims, c1983)

- Montagne blanche: roman (Paris: Gallimard, c1986)

- Netchaïev est de retour-- : roman (Paris: J.C. Lattès, c1987)

See also

In Spanish: Jorge Semprún para niños

In Spanish: Jorge Semprún para niños

- List of Spanish Academy Award winners and nominees

- Calle Mayor (film)