Le Grand Village Sauvage, Missouri facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Le Grand Village Sauvage, Missouri

|

|

|---|---|

|

Abandoned village

|

|

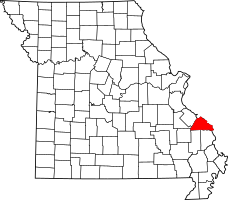

Location of Perry County, Missouri

|

|

| Country | United States |

| State | Missouri |

| County | Perry |

| Township | Union |

Le Grand Village Sauvage (which means 'the big wild village' in French) was a Native American village. It was also called Chalacasa. This village was located near Old Appleton in Perry County, Missouri, United States.

The village was home to Shawnee and Delaware Indian people. They had moved there from Ohio and Indiana.

Contents

Village Names: Chalacasa and Le Grand Village Sauvage

The Shawnee people often named their villages Chillicothe or Chilliticaux. These names meant 'a place of residence.' Their biggest town along Apple Creek was called Chalacasa. This name came from their older town on the Scioto River in Ohio.

The French called Chalacasa Le Grand Village Sauvage, meaning 'the big wild village'. Americans sometimes called it The Big Village or The Big Shawnee Village.

History of Le Grand Village Sauvage

Moving West: Native American Immigration

In the 1700s, more and more American settlers moved west. This forced many Native American tribes to leave their homes. The Spanish leaders in Upper Louisiana (also known as the Illinois Country) saw these tribes as possible new residents. They wanted them to settle between Ste. Genevieve and Cape Girardeau.

The Spanish encouraged the Shawnee and Delaware to move there. They hoped these tribes would protect the area from attacks by the Osage tribe. They also wanted them to help defend against a possible American invasion.

The Shawnee and Delaware had been forced from their lands in the Ohio Valley. They had settled in what is now Ohio and Indiana. By the 1780s, they were looking for new places to live. This was because they had supported the British in the American War of Independence.

Around this time, Don Louis Lorimier also moved to Upper Louisiana. He was a French-Canadian Métis who had fought with the British. Lorimier had a trading post in Ohio and was close with the Shawnee. He encouraged many of them to settle in Upper Louisiana. In 1787, Lorimier suggested a plan to bring the Shawnee and Delaware, who had lost their lands, to Spanish territory.

In 1793, Baron de Carondelet approved Lorimier's plan. He allowed these tribes to settle in the New Bourbon district. This area was along the Mississippi River between the Missouri River and Arkansas River. The Spanish government wanted Lorimier to convince them to settle there. This was easier because the Shawnee and Delaware disliked the Americans. The Americans had defeated them in battle, leading to the Treaty of Greenville in 1795.

Settling in Missouri

The Shawnee and Delaware mostly settled between Cinque Hommes and Flora Creeks. This area was above Cape Girardeau. Their main settlement was around Apple Creek, bordering Perry County and Cape Girardeau County.

The Spanish gave them a large area of land, about 750 square miles. This land included open prairies, woodlands, and fertile river areas. It was big enough for several Native American villages and hunting grounds. These tribes, who had adopted some American ways, relied more on farming and raising animals than on hunting.

The tribes usually worked together on important issues. However, they built separate villages. The largest Shawnee village was Le Grand Village Sauvage. It had about 400 people. It was built on a hill above Apple Creek, west of where Old Appleton is today.

A small road, called the Shawnee Trace, connected Don Louis Lorimier's trading post in Cape Girardeau to Le Grand Village Sauvage. This road continued north to La Saline, Ste. Genevieve, and St. Louis. This trace was part of the Royal Road. This road connected several Spanish administrative posts and Native American villages. Many officials and outsiders traveled through these villages.

By 1804, the land had too many settlers for good hunting. The Shawnee and Delaware believed the land was only for them. However, local leaders gave land to white settlers, sometimes as close as three miles from the villages. These leaders seemed to think they could approve settlements on empty land. They might have seen the hunting lands around the villages as empty, similar to how other hunting lands used by Americans were seen. Rules about only giving land that didn't conflict with other claims were usually followed strictly. But this didn't seem to apply to the Native American land. By the end of Spanish rule, about one hundred white settlers lived on scattered farms in the area. Most were on the edges of the Native American land.

The Shawnee and Delaware protested these new settlers. But they had little power with the authorities, except through Lorimier. The first white settlers in the area didn't seem to bother them much. Some even worked as gunsmiths or other skilled workers who traded with them.

Even with protests, the Shawnee and Delaware fulfilled the reasons the Spanish invited them. They were good at keeping the Osage away. Years later, Americans used them for the same purpose in Oklahoma, as a buffer between the Osage and Cherokee. Early on, the Shawnee said that Spanish Illinois (Upper Louisiana) was not peaceful because of the Osages. They threatened to return to the United States. The Shawnee were especially upset that the Spanish expected them to fight the Osages. At the same time, the Spanish continued to trade and give gifts to the Osages. They offered no help to the Shawnee and Delaware when the Osages attacked them.

A Time of Change: Witch-Hunts

A Shawnee spiritual leader named Tenskwátawa, known to white settlers as "the Shawnee prophet," began to teach new ideas. He urged Native Americans to return to their old ways of life. He wanted them to stop using customs from white settlers. Many Native Americans followed him, especially those who had suffered from diseases and losing their lands. In 1805, Tenskwátawa led a religious movement. This happened after a smallpox outbreak among the Shawnee led to a series of witch-hunts.

These witch-hunts eventually reached the Shawnee in Upper Louisiana. Around 1808–1809, the Native American communities along Apple Creek became convinced that witchcraft was being practiced. Sadly, about 50 women died in 12 months because of these beliefs. Accusations against women were often based on someone saying they saw the accused witch as an owl or another animal. This period of fear ended suddenly when Tecumseh arrived. He was busy planning to unite all Native American tribes to stop white settlers from moving onto their lands.

White Settlers Move In

Between 1811 and 1814, problems grew as more white settlers arrived. Missouri's white population more than doubled during this time. Many white settlers crossed the Mississippi River, leading to more trouble for the villages along Apple Creek.

From 1811 to 1814, the Shawnee along Apple Creek reported losing many animals. This included over sixty-five hogs, forty-nine cattle, and forty-eight horses. Wapapilethe, a chief from Apple Creek, returned from a winter hunt to find his house broken into and everything stolen. Wapapilethe knew a white man who had illegally settled on his land and robbed him and other Shawnees. However, Native Americans could not testify against white people in court, so he could not do anything legally.

The Apple Creek Shawnees were powerless to stop the harassment and thefts. They complained that "the whites do not steal these things merely for their value, but more to make us abandon our land and take if for themselves." In another case, a Shawnee man was beaten by a white man who then took his land and property. Even with strong evidence and protests from the Shawnees and Pierre Menard, a local judge refused to take the case. This allowed the time limit for prosecuting the crimes to pass.

Moving Again: Emigration and Removal

Both the Spanish and later the American governments had given the Native Americans rights to their lands. They had also ordered all white settlers to move off these lands. However, many Shawnee and Delaware slowly moved west as white settlers advanced. They created new communities further west in Missouri, in Stoddard and Greene counties.

In a treaty signed in St. Louis in 1815, the American government ordered all white settlers to leave the Shawnee and Delaware lands. But this help was only temporary. Between 1815 and 1819, the Shawnee population in southeastern Missouri dropped from 1,200 to only 400. Just ten years after the Treaty of St. Louis, white settlers had moved in so much that these tribes had to sell their Spanish land grant. They left Missouri for a new home further west.

Missouri became the 24th state in 1821. In 1825, the U.S. government worked to end any remaining Shawnee claims to the Spanish land grant. In November, 1,400 Shawnee people in Missouri agreed to a treaty signed in St. Louis with William Clark. They traded their lands along Apple Creek for 2,500 square miles in eastern Kansas. They also received $14,000 for moving costs and $11,000 to pay debts to white traders. The treaty also allowed any of the 800 Ohio Shawnee who wanted to join them in Kansas.

When they settled on the south side of the Kansas River the next year, the Shawnee were the first of the eastern Algonquin tribes to settle in Kansas. However, problems arose. The very traditional Black Bob's band did not want to join the Ohio Shawnee. Instead of moving to Kansas after the treaty, they went south and settled in Arkansas. For the next two years, nothing could convince them to move. After a threat of military force, they finally settled at Olathe in 1833.

How Many People Lived There?

The New Bourbon census of 1797 reported that 70 Shawnee and 120 Delaware families lived in villages on the north side of Apple Creek. It's possible that just as many families lived in villages south of Apple Creek. Le Grand Village Sauvage itself had about 400 people. It was estimated that a total of 3,000 Shawnee and Delaware people lived in these communities between Cinque Hommes and Flora creeks.

The Shawnee and Delaware on Apple Creek had a good amount of intermarriage with French and American people. They had also adopted some French and American ways of life. This included people of mixed heritage, both French and American. It also included white people, likely orphans or captives from wars, who had been raised as Native Americans. Spanish officials at the time noted that the Apple Creek villages had as much "white blood" as French villages had "Native American blood."

Village Life and Homes

Some houses were built in the French poteaux en terre (posts-in-the-ground) or poteaux-sur-sol (post-on-a-sill) style. This meant vertical log posts were set close together in the ground or on a sill. Clay was used to fill the gaps between the logs. Other houses were built in the American log cabin style, with horizontal squared logs. Some of these were two stories high and had shingled roofs.

The villages also had granaries for storing grain and barns for cattle and horses. The villages looked like permanent settlements. Fields of corn, barley, pumpkins, melons, and potatoes surrounded the villages. These fields were enclosed by fences. The Shawnee and Delaware also raised chickens, cattle, hogs, and horses.

The Shawnee and Delaware paid attention to how they dressed. The women wore their hair tied close to their heads and covered with animal skins. They were also very careful with their children, more so than some other Native American groups. They would stretch the cartilage of their ears to make them longer and hang silver star-shaped ornaments from them. They wore crosses around their necks and bands or crowns covered with shiny decorations on their heads. For special celebrations, they used a lot of red and black paint to decorate their bodies.

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |