Ear facts for kids

The ear is a super important part of your body that lets you hear all sorts of sounds! People and most mammals have ears, but did you know some animals hear in different ways? For example, Spiders use tiny hairs on their legs to "hear" vibrations.

For us, the ear works like a funnel, guiding sound waves deep inside. These sound waves create tiny vibrations that are then sent to your brain through a network of nerves. This whole amazing system is called the auditory system.

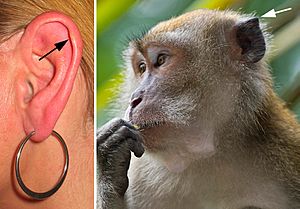

The part of your ear that you can see on the outside is called the pinna.

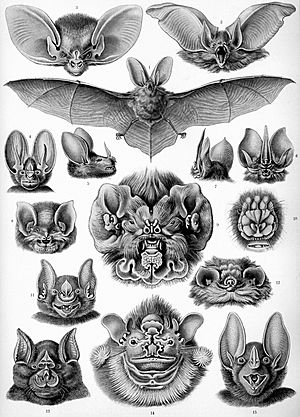

Ears aren't just for hearing! African elephants have huge ears that help them cool down when it's really hot. Bats use their ears to find food in the dark by sending out sounds and listening for the echoes (this is called echolocation). Some animals even use their ears to send signals to each other.

Contents

Parts of the Ear

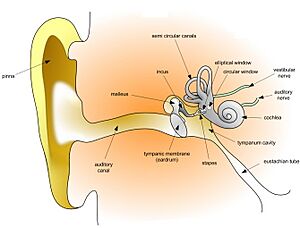

Your ear has three main parts: the outer ear, the middle ear, and the inner ear. The ear canal (which is part of your outer ear) is separated from the air-filled tympanic cavity (in your middle ear) by the eardrum.

The middle ear holds three tiny bones called ossicles. These bones help send sound vibrations further inside. It's also connected to your throat by a tube called the Eustachian tube.

The inner ear contains special parts like the cochlea (for hearing) and the semicircular canals (for balance).

The Outer Ear: What You See

The outer ear is the part you can see. It includes the pinna (that fleshy, visible part), the ear canal, and the outer layer of your eardrum.

The pinna has a curving outer edge called the helix and an inner curved edge called the antihelix. It opens into your ear canal. The tragus is a small bump that partly covers the ear canal opening.

Your ear canal is about 1 inch (2.5 cm) long. The first part is made of cartilage, and the part closer to your eardrum is made of bone. The skin inside your ear canal has special glands that make ear wax to protect your ear. The ear canal ends at the outside surface of your eardrum.

Some animals can move their ears to hear better, but in humans, the ear muscles don't do much. The way your two ears are placed helps your brain figure out where sounds are coming from. It compares when sounds arrive at each ear and how loud they are.

The Middle Ear: Tiny Bones, Big Job

The middle ear is located between your outer ear and inner ear. It's an air-filled space called the tympanic cavity. Inside, you'll find the three ossicles (tiny bones) and the Eustachian tube. It also has two small openings called the round and oval windows.

The ossicles are the smallest bones in your body! They are:

- The malleus (shaped like a hammer)

- The incus (shaped like an anvil)

- The stapes (shaped like a stirrup)

These three bones work together to take sound vibrations from your eardrum and make them stronger before sending them to your inner ear. The stapes is the smallest named bone in your body! The middle ear is also connected to the upper part of your throat by the Eustachian tube.

Here's how the ossicles work: 1. The malleus gets vibrations from your eardrum. 2. It passes these vibrations to the incus. 3. The incus then sends the vibrations to the stapes. 4. The stapes pushes on the oval window, which makes the fluid inside your cochlea (in the inner ear) move.

The round window helps the fluid in your inner ear move freely. The ossicles are amazing because they can make sound waves nearly 15 to 20 times stronger!

The Inner Ear: Hearing and Balance Control

The inner ear is hidden deep inside your temporal bone. It has a complex bony area called the bony labyrinth. In the center, there's a space called the vestibule with two small fluid-filled parts: the utricle and saccule. These connect to the semicircular canals and the cochlea.

- There are three semicircular canals, set at right angles to each other. They are in charge of your sense of dynamic balance (when you're moving).

- The cochlea is shaped like a snail shell and is responsible for your sense of hearing.

These structures together form the membranous labyrinth.

The inner ear starts at the oval window, which receives vibrations from the middle ear. These vibrations travel into a fluid called endolymph that fills the inner ear. The endolymph moves into the cochlea, which has three fluid-filled spaces. Inside the cochlea, there are tiny hair cells that change these mechanical vibrations into electrical signals. These signals are then sent to your brain.

How Your Ears Work

How We Hear

Sound waves travel through your outer ear, get boosted by your middle ear, and then are sent to the vestibulocochlear nerve in your inner ear. This nerve carries the information to the temporal lobe of your brain, where it's recognized as sound!

Here's a step-by-step look: 1. Sound waves enter your outer ear and hit your eardrum, making it vibrate. 2. The malleus (first ossicle) rests on the eardrum and picks up these vibrations. 3. The vibrations travel through the incus and stapes to the oval window. 4. Two tiny muscles, the tensor tympani and stapedius, help control how much the eardrum vibrates, protecting your ear from very loud noises. 5. When the oval window vibrates, it makes the fluid inside your inner ear (the endolymph) move.

The inner ear is where the magic happens: it changes the vibrations into signals for your brain. The fluid in the inner ear moves against tiny hair cells. When these hair cells move, they create an electrical signal (an action potential) that travels along the vestibulocochlear nerve to your brain.

Humans can usually hear sounds with frequencies between 20 Hz and 20 kHz. Sounds below 20 Hz are called infrasound, and sounds above 20 kHz are called ultrasound. Most hearing problems happen because of issues in the inner ear, not usually in the nerves or brain.

How We Balance

Your ears also play a huge role in helping you keep your balance, whether you're standing still or moving! The ear helps with two kinds of balance:

- Static balance: This helps you feel the effects of gravity and know your body's position when you're not moving.

- Dynamic balance: This helps you sense acceleration and keep your balance when you're moving.

Static balance comes from two small sacs in your inner ear called the utricle and saccule. These sacs have special cells with tiny hairs covered by a jelly-like layer. Inside this jelly are tiny calcium carbonate crystals called otoliths. When you move your head, these otoliths shift, bending the hairs. This bending creates an electrical signal that is sent to your brain, telling it about your head's position.

Dynamic balance comes from the three semicircular canals. These canals are at right angles to each other and are filled with fluid. When you change how fast you're moving, the fluid inside these canals shifts. This movement pushes on special hair cells, creating signals that are sent to your brain, helping you stay balanced. This also helps your eyes stay focused when you're moving!

How Your Ears Grow

Your ear develops in three separate parts during embryogenesis (when you're growing inside your mother): the inner ear, the middle ear, and the outer ear. Each part comes from a different layer of cells.

Inner Ear Development

The inner ear is the first part to start forming, around the 22nd day of an embryo's development. It starts as two thickenings on the sides of the head, which then fold inward to form small sacs. These sacs will eventually become the inner ear structures, surrounded by bone.

Around the 33rd day, these sacs start to change into the utricle, semicircular canals, saccule, and cochlea. The cochlea, which is shaped like a spiral, starts to form around the sixth week.

Middle Ear Development

The middle ear and its parts grow from structures called pharyngeal arches. The space for the middle ear and the Eustachian tube develop from a pouch between these arches. The three tiny ossicle bones (malleus, incus, and stapes) usually appear during the first half of fetal development. The malleus and incus come from the first arch, and the stapes comes from the second.

Outer Ear Development

Unlike the inner and middle ear, the ear canal comes from a different part of the embryo. It's fully formed by the end of the 18th week of development. The eardrum is made of three layers. The pinna (the visible part of your ear) forms from six small bumps that join together. The outer ears first develop in the lower neck area and then move upwards to their final position, level with your eyes, as your jaw grows.

Ear Problems

Hearing Loss

Hearing loss can be partial (you can still hear some things) or total (you can't hear anything). It can happen because of an injury, a problem you're born with, or other health reasons.

- Conductive hearing loss happens when there's a problem in your outer or middle ear. This could be from earwax blocking the ear canal, problems with the ossicles (the tiny bones), or holes in the eardrum. Infections in the middle ear that cause fluid buildup can also lead to this. Operations like Tympanoplasty can repair the eardrum and ossicles.

- Sensorineural hearing loss happens when there's damage to your inner ear, the vestibulocochlear nerve, or the brain.

If hearing loss is severe, Hearing aids or cochlear implants can help. Hearing aids make sounds louder and are best for conductive hearing loss. Cochlear implants work by sending sound as nervous signals directly to the brain, bypassing the damaged cochlea.

Ears in Other Animals

The pinna helps direct sound into the ear canal. In some mammals, the complex shapes of their ears help them focus on sounds, especially for animals that use echolocation, like bats. You can see these complex ear shapes in animals like the aye-aye and bat-eared fox.

Some large primates, like gorillas, orang-utans, and even humans, have ear muscles that don't really work anymore. These are called vestigial structures, meaning they are left over from ancestors where they were useful. This shows how different species are related. While most humans can't move their ears, some can! And if you can't move your ears, you can usually turn your head easily to help you hear better.

Animals with mobile pinnae (ears that can move), like horses, can aim each ear independently to better find where a sound is coming from.

Invertebrates

Only animals with backbones (vertebrates) have ears. But many invertebrates (animals without backbones) can still detect sound using other special organs.

Insects often use tympanal organs to hear sounds from far away. These organs can be on their head or other parts of their body. Some insects have incredibly sensitive hearing! For example, the female cricket fly Ormia ochracea has tympanal organs on her abdomen that work like tiny eardrums. Because they are connected, they help her figure out the exact direction of a male cricket's call, even if the sound arrives at each "ear" only a tiny fraction of a second apart. This helps her find the cricket to lay her eggs on it.

Simpler animals like spiders and cockroaches have tiny hairs on their legs that can detect sound vibrations. Caterpillars also have body hairs that help them sense vibrations and react to sounds.

Related pages

Images for kids

-

African bush elephant Loxodonta africana -

Fennec fox (desert regions) Vulpes zerda -

Arctic fox Vulpes lagopus -

Domestic rabbit – French Lop breed Oryctolagus cuniculus

See also

In Spanish: Oído para niños

In Spanish: Oído para niños