Military operations in North Africa during World War I facts for kids

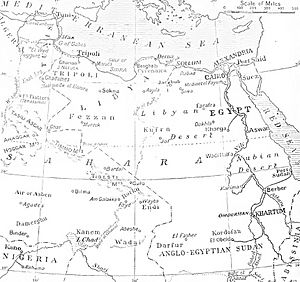

Conflicts happened in North Africa during World War I (1914–1918). These fights were between the Central Powers (like the Ottoman Empire and German Empire) and the Entente (like the British Empire and Kingdom of Italy) and their friends.

One big conflict was the Senussi Campaign. The Senussi people of Libya joined the Ottomans and Germans. They fought against the British and Italians. On November 14, 1914, the Ottoman leader called for a holy war, known as a jihad. He hoped this would make the British move their soldiers away from the Sinai and Palestine Campaign. Italy wanted to keep the lands they had won in the Italo-Turkish War. The Senussi Campaign lasted from November 23, 1915, to February 1917.

In the summer of 1915, the Ottoman Empire convinced the Senussi leader, Ahmed Sharif es Senussi, to attack Egypt from the west. They wanted him to start a rebellion to help an Ottoman attack on the Suez Canal from the east. The Senussi crossed the border into Egypt in November 1915. At first, British forces pulled back. But then they defeated the Senussi in several battles, like the action of Agagia. By March 1916, the British had taken back the coastal areas. The Western Frontier Force of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, which included soldiers from South Africa, helped with this.

Further west, people in lands recently taken by European powers from the Ottoman Empire used the war to try and get their lands back. Uprisings like the Zaian War, Volta-Bani War, and Kaocen Revolt happened in Morocco and other parts of West Africa. These were against the French colonialists. Some of these fights lasted even longer than World War I itself. In Sudan, the Anglo-Egyptian Darfur Expedition happened. This was against the Sultan of Darfur, who was thought to be planning to invade Egypt at the same time as the Senussi. The British used small groups of soldiers with cars, airplanes, and radios. This made them very effective and fast, often surprising their enemies.

Why the War Started in North Africa

German and Ottoman Plans

In 1914, the Central Powers, Germany and the Ottoman Empire, started a plan to fight in areas far from Europe. They hoped to cause problems for the European colonial empires. They thought about encouraging people in these colonies to rebel. This idea was appealing because Germany was not as strong in Europe. They wanted to turn their weakness in colonies into an advantage.

On August 20, 1914, a German general named Moltke asked for Islamic rebellions in Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria. Germany wanted its diplomats to create armies that would fight for independence. The Foreign Office in Germany pushed for a pan-Islamic plan, using the Ottoman Empire and its army. The Ottomans joined the war to escape European control. They also had their own plans for North Africa, Central Asia, and the Near East.

In October 1914, Enver Pasha, an Ottoman leader, made a war plan that included a holy war and an invasion of Egypt. On November 14, 1914, the Sheikh-ul-Islam (a religious leader) declared a holy war. He called on all Muslims to fight the Entente and their allies. But he did not include Italy, which was neutral then. He also excluded Muslims under German or Austro-Hungarian rule. This message reached North, East, and West Africa. Enver Pasha ordered a special group, the Teskilat-i Mahsusa, to spread propaganda, cause trouble, and carry out attacks. They had done similar things in the war against Italy in Libya.

Allied Plans

Before 1914, European colonial powers worried about a holy war. In August 1914, Charles Lutaud, the Governor of Algeria, expected a rebellion. On November 5, he tried to stop the Ottoman call to arms. He said the Ottomans were just puppets of Germany. The French were helped by the British Royal Navy, who could break codes. This helped them know about German submarine landings and stop the Central Powers' plans.

French power in Morocco helped prevent attempts to overthrow their rule. German prisoners of war were even used for forced labor in Morocco and Algeria. This showed how strong France was. Most French regular soldiers were sent to France in 1914. They were replaced by local troops in Morocco. But on the border of Algeria and Libya, the Senussi fought the Italian army. This led the French to let the garrisons in Ghadames and Ghat retreat into Algeria. Then, they were rearmed to recapture Ghadames in January 1915. This was part of France's plan to get Italy to join the war.

North Africa in 1914

Before 1906, the Senussi were a peaceful religious group in the Sahara Desert. They were against extreme ideas. But when the Italians invaded Libya in 1911 and took over the coast, the Senussi fought back from inside the country. During their fight against the Italians, the Senussi usually had good relations with the British in Egypt.

Italy had taken over Libya in 1911 after the Italo-Turkish War. France had taken over Morocco in 1912. But neither country had full control when World War I began. After losing the province of Trablusgarp to Italy in 1911–1912, the local Sanusi people kept fighting the Italians. Sanusi fighters, led by Ahmad al-Sharif, stopped Italy from fully controlling areas in southwest Libya and southern Tripolitania. The Ottoman government kept helping these local tribes.

Military Operations in North Africa

Morocco: The Zaian War (1914–1921)

Germany and the Ottomans tried to cause trouble in French colonies. They worked with local leaders who had been removed by the French. Spanish officials in the area allowed propaganda and money to be given out. But a German plan to smuggle 5,000 rifles and 500,000 bullets through Spain was stopped. The Ottoman Teskilat-i Mahsusa had agents in North Africa, but only two in Morocco.

The Zaian War was fought between France and the Zaian confederation of Berber tribes in French Morocco. This war lasted from 1914 to 1921. Morocco had become a French protectorate in 1912. The French army tried to expand its control eastward through the Middle Atlas mountains towards French Algeria. The Zaians, led by Mouha ou Hammou Zayani, quickly lost the towns of Taza and Khénifra. But they caused many losses for the French.

The French responded by creating special fighting groups called groupes mobiles. These groups combined regular and irregular infantry, cavalry, and artillery. By 1914, the French had 80,000 soldiers in Morocco. But two-thirds of them were sent to France from 1914 to 1915. More than 600 French soldiers were killed at the Battle of El Herri on November 13, 1914. Hubert Lyautey, the French governor, reorganized his forces. He decided to attack rather than just defend. The French took back most of the lost land. This happened even though the Central Powers gave information and money to the Zaian Confederation. The Zaians still launched raids that caused losses for the French, who were already short on soldiers.

French West Africa: The Kaocen Revolt

The Senussi leaders in the Fezzan town of Kufra Oasis declared a holy war against the French in October 1914. The Sultan of Agadez told the French that the Tuareg people were still loyal. But the followers of Kaocen surrounded the French army post on December 17, 1916. Kaocen, his brother Mokhtar Kodogo, and about 1,000 Tuareg fighters, armed with rifles and a field gun, defeated several French relief groups. The Tuareg took over the main towns of the Aïr (in modern northern Niger). These towns included Ingall, Assodé, and Aouderas.

On March 3, 1917, a large French force from Zinder rescued the Agadez post. They then began to take back the towns. The French took harsh revenge on the townspeople, especially against religious leaders called marabouts. Many of these people were not Tuareg or rebels. The French quickly killed 130 people in public in Agadez and Ingal. Kaocen fled north and was killed in Mourzouk in 1919. Mokhtar Kodogo was killed by the French in 1920. He had led a revolt by the Toubou and Fula people in the Sultanate of Damagaram.

French West Africa: The Volta-Bani War

A big uprising against the French happened in the south of Upper Senegal and Niger in 1915–16. This conflict is not well known because of wartime censorship. After the war, in 1919, the affected region was separated to form its own colony, Upper Volta (which is now Burkina Faso).

Egypt–Libya: The Senussi Campaign

Britain declared war on the Ottoman Empire on November 5, 1914. In the summer of 1915, Turkish messengers, including Nuri Bey (Enver Pasha's brother) and Jaafar Pasha (an Arab serving in the Turkish army), made a deal with the Grand Senussi, Sayyid Ahmed ash-Sharif. The Senussi planned to attack the British in Egypt from the west. This would happen during the Ottoman attack through Palestine against the Suez Canal.

By late 1915, many British soldiers in Egypt had been sent to Gallipoli and Mesopotamia. Western Egypt was guarded by the Egyptian coastguard. The Ottomans and Germans sent modern weapons to the Senussi by submarine. German and Turkish officers also arrived by submarine on May 19, 1915. They landed west of Sollum and set up their headquarters at Siwa.

The Senussi gathered 5,000 foot soldiers and other irregular troops. They had Turkish artillery and machine-guns. They planned attacks along the coast towards Sollum, Mersa Matruh, and Da'aba on the way to Alexandria. They also planned attacks from Siwa through the oases of Bahariya, Farafra, Dakhla, and Kharga, which are about 100 miles (160 km) west of the Nile. The Senussi crossed the Egyptian–Libyan border on November 21, 1915, to start the coastal campaign. At the border, 300–400 men attacked a border post but were pushed back. In February 1916, Sayed Ahmed joined the Senussi against the oases. Several oases were captured but then lost in October 1916 to British forces. The Senussi left Egypt in February 1917. In November, Senussi forces took over Jaafar.

Coastal Operations

On November 6, the German submarine U-35 sank a ship called HMS Tara in the Bay of Sollum. The submarine came to the surface and sank the coastguard gunboat Abbas. It also badly damaged Nur el Bahr with its deck gun. On November 14, the Senussi attacked an Egyptian position at Sollum. On the night of November 17, some Senussi fired into Sollum, and another group cut the coast telegraph line. The next night, 300 Muhafizia (Senussi fighters) took over a monastery at Sidi Barrani, 48 miles (77 km) beyond Sollum. On the night of November 19, a coastguard was killed. An Egyptian post was attacked 30 miles (48 km) east of Sollum on November 20.

The British pulled back from Sollum to Mersa Matruh, 120 miles (190 km) further east. Mersa Matruh had better facilities for a base. The Western Frontier Force was created there. On December 11, a British group sent to Duwwar Hussein was attacked along the Matruh–Sollum track. In the Affair of Wadi Senba, they drove the Senussi out of the wadi. The scouting continued. On December 13, at Wadi Hasheifiat, the British were attacked again. They were held up until artillery arrived in the afternoon and forced the Senussi to retreat.

The British returned to Matruh until December 25. Then they made a night advance to surprise the Senussi. At the Affair of Wadi Majid, the Senussi were defeated but managed to retreat to the west. Airplanes scouting found more Senussi camps near Matruh at Halazin. This camp was attacked on January 23, in the Affair of Halazin. The Senussi skillfully fell back and then tried to surround the British from the sides. The British were pushed back on the sides as their center advanced. They defeated the main group of Senussi, who again managed to retreat.

In February 1916, the Western Frontier Force got more soldiers. A British group was sent west along the coast to take back Sollum. Airplanes scouting found a Senussi camp at Agagia. This camp was attacked in the action of Agagia on February 26. The Senussi were defeated. Then they were stopped by the Dorset Yeomanry, who charged across open ground under machine-gun and rifle fire as the Senussi pulled back. The British lost half their horses and 58 of 184 men. But they stopped the Senussi from escaping. Jaafar Pasha, the commander of the Senussi forces on the coast, was captured. British forces re-occupied Sollum on March 14, 1916. This ended the coastal campaign.

Oases Operations

On February 11, 1916, the Senussi and Sayyid Ahmed ash-Sharif took over the oasis at Bahariya. This oasis was then bombed by RAF aircraft. The oasis at Farafra was taken over at the same time. Then the Senussi moved to the oasis at Dakhla on February 27. The British responded by forming the Southern Force at Beni Suef. Egyptian officials at Kharga were pulled out, and the oasis was taken over by the Senussi. But they left without being attacked. The British reoccupied the oasis on April 15. They began to extend the light railway, which ended at Kharga, to the Moghara Oasis.

The mainly Australian Imperial Camel Corps, patrolling on camels and in light Ford cars, cut off the Senussi from the Nile Valley. The Senussi soldiers at Bahariya detected preparations to attack their oasis. They pulled back to Siwa in early October. The Southern Force attacked the Senussi in the Affairs in the Dakhla Oasis (October 17–22). After this, the Senussi retreated to their base at Siwa.

In January 1917, a British group, including the Light Armoured Car Brigade with Rolls-Royce Armoured Cars and three Light Car Patrols, was sent to Siwa. On February 3, the armored cars surprised and fought the Senussi at Girba. The Senussi retreated overnight. Siwa was entered on February 4 without a fight. But a British ambush party at the Munassib Pass was stopped. The escarpment was too steep for the armored cars. The light cars managed to go down the escarpment and captured a convoy on February 4. The next day, the Senussi from Girba were stopped. But they managed to set up a post that the cars could not reach. This warned off the rest of the Senussi. The British force returned to Matruh on February 8. Sayyid Ahmed pulled back to Jaghbub. Talks between Sayed Idris and the Anglo–Italians had started in late January. News of the Senussi defeat at Siwa sped up these talks. In the Accords of Akramah, Idris accepted the British terms on April 12 and Italy's terms on April 14.

Sudan: The Darfur Expedition

On March 1, 1916, fighting began between the Sudanese government and the Sultan of Darfur. The Anglo-Egyptian Darfur Expedition was carried out to stop an imagined invasion of Sudan and Egypt. This invasion was thought to be planned by the Darfurian leader Sultan Ali Dinar. It was believed to be timed with a Senussi advance into Egypt from the west. The Sirdar (commander) of the Egyptian Army put together a force of about 2,000 men at Rahad. This was a railhead 200 miles (320 km) east of the Darfur border.

On March 16, the force crossed the border in trucks from a forward base set up at Nahud, 90 miles (140 km) from the border. They had support from four airplanes. By May, the force was close to Darfur's capital, El Fasher. At the Affair of Beringia on May 22, the Fur Army was defeated. The Anglo-Egyptian force captured the capital the next day. Dinar and 2,000 followers had left. As they moved south, they were bombed from the air.

French soldiers in Chad, who had returned from the Kamerun campaign, stopped the Darfurians from retreating west. Dinar pulled back into the Marra Mountains, 50 miles (80 km) south of El Fasher. He sent messengers to discuss terms. But the British believed he was just delaying and ended the talks on August 1. Disagreements among Dinar's followers reduced his force to about 1,000 men. Anglo-Egyptian outposts were pushed out from El Fasher, to the west and south-west after the August rains.

A small fight happened at Dibbis on October 13. Dinar started talks again, but he was again suspected of bad faith. Dinar fled south-west to Gyuba. A small force was sent to chase him. At dawn on November 6, a combined Anglo-Egyptian force attacked in the Affair of Gyuba. Dinar's remaining followers scattered, and the Sultan's body was found 1 mile (1.6 km) from the camp. After this expedition, Darfur became part of Sudan.

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |