Mozarabs facts for kids

The Mozarabs were Christians who lived in Iberia (modern-day Spain and Portugal) when it was ruled by Muslims. This period lasted from about 711 to 1492. After the Muslim conquest of the Visigothic Kingdom, many Christians came under Muslim control.

At first, most Mozarabs kept their Christian faith and continued to speak their local languages, which came from Latin. Over time, many people converted to Islam. By the year 951, about half of the population had become Muslim. Mozarabs were also influenced by Arab customs and knowledge. Sometimes, converting to Islam even helped them gain a higher social status.

The local languages spoken by both Christians and Muslims were called Andalusi Romance or the Mozarabic language. These languages had many words from Arabic. Most Mozarabs were Catholics who followed a special Christian practice called the Mozarabic Rite. Under Islamic law, Christians had to pay a tax called the jizya. This meant they didn't have to fight in wars. They also kept their own laws, which were based on old Roman and Visigothic laws.

Most Mozarabs were descendants of Spanish Christians. They spoke Mozarabic, which was a form of late Latin. Some were also from the Visigothic ruling families who chose not to convert to Islam or move north after the conquest.

Some Mozarabs were even Arab or Berber Christians, or Muslims who converted to Christianity. These people felt at home among the original Mozarabs because they spoke Arabic. A famous example was Umar ibn Hafsun, a Muslim rebel leader who became a Christian.

Mozarabs lived in separate communities within large Muslim cities like Toledo, Córdoba, Zaragoza, and Seville.

Contents

What Does "Mozarab" Mean?

The word Mozarab (from the Arabic word musta‘rab, meaning "Arabized") first appeared in Christian writings in the 11th century. This term is sometimes used for all Christians in al-Andalus, but it's not always exact. This is because many Christians living in Islamic Spain tried to avoid becoming too "Arabized."

Muslims did not use the term Mozarab to describe Christians. Instead, they called Christians naṣārā (meaning 'Nazarenes') or referred to them by their legal status, like ahl adh-dhimma ('people of the covenant').

How Mozarabs Lived Under Muslim Rule

Christians and Jews were known as dhimmi under Sharia (Islamic law). Dhimmi were allowed to live in Muslim society, but they had to pay the jizya tax. They also had to follow certain religious, social, and economic rules. Even with these rules, dhimmi were protected by Muslim rulers and did not have to fight in wars because they paid the tax.

Mozarabs had their own courts and leaders. Some even held important jobs in the Islamic government. For example, Rabi ibn Zayd, a palace official, wrote the famous Calendar of Córdoba between 961 and 976. He also went on diplomatic trips and was later made a bishop. Another example is Paternus, a Mozarabic bishop, who was sent as a messenger to a Christian king in 1064.

Muslim rulers encouraged people to convert to Islam. Many Mozarabs converted to avoid the heavy jizya tax. Becoming Muslim also offered new opportunities, improved their social standing, and led to better living conditions and more skilled jobs. However, if someone who was raised Muslim or had converted to Islam later left the faith, it was a crime punishable by death.

Until the mid-9th century, relations between Muslims and Christians in Al-Andalus were generally friendly. Early Christian resistance to the Muslim conquerors was not successful. In some areas, like Murcia, Christian leaders agreed to pay tribute (taxes) in exchange for keeping their traditional freedoms. This meant their property and local laws were respected. In these cases, even the old Visigothic lords remained in charge.

In the western part of al-Andalus, which included modern-day Portugal, Mozarabs were the majority of the population.

The Muslim geographer Ibn Hawqal wrote in the 10th century that Mozarab peasants often revolted on large farms. There is also evidence that Mozarabs fought to defend border towns and even joined in raids against Christian neighbors or in fights between Muslim groups.

There is little evidence of Christian resistance in al-Andalus in the 9th century. Many Mozarabs moved north. For example, the Mozarab community in Lleida was once ruled by a count and had its own judges, but this system disappeared later on.

Mozarab merchants traded in Andalusi markets, but they were not very powerful or numerous until the 12th century. This was because they generally saw trade as a low-status job, unlike Jewish and Muslim societies where trade was often combined with other important roles like politics or medicine.

It is often thought that Mozarab merchants were a key link between the Christian north and Muslim south of Iberia. However, most trade between al-Andalus and Christian regions was handled by Jewish and Muslim traders. This changed when European trade grew in the 11th and 12th centuries, and Christian traders from northern Iberia, France, and Italy took over. By the mid-13th century, Christian traders controlled all international trade.

Mozarabs in al-Andalus often had contact with other Christians in the northern kingdoms like Kingdom of Asturias and the Marca Hispanica (a region influenced by the Franks). The Christian culture in the north was not as advanced as that of the Mozarabs in the south, because al-Andalus was very prosperous. Because of this, Christian refugees from al-Andalus were always welcomed in the north, where their descendants became influential. Many Mozarabs moving north likely helped the Christian kingdoms grow.

For much of the 9th and 10th centuries, Mozarab immigrants helped boost Christian culture in the north. They brought knowledge and helped shape Christian ideas. Mozarab scholars and clergy actively searched for old manuscripts and traditions from the Visigothic Catholic heartlands in central and southern Iberia. Many Mozarabs also took part in local revolts during a time of great unrest in the late 9th century.

Mozarabs were able to fit into Moorish culture while keeping their Christian faith. Some scholars thought this meant they were very loyal to the Catholic Church. However, historian Jaume Vicens Vives offered another view. He noted that when Emperor Charlemagne tried to capture Zaragoza, an important Mozarab city, the Mozarabs refused to help him. Vives believed that Mozarabs were mainly focused on their own interests and knew they could benefit by staying close to the Moors.

The Mozarab population in al-Andalus steadily declined towards the end of the Reconquista (the Christian reconquest of Spain). This happened because people converted to Islam, moved north during times of trouble in the 9th and 10th centuries, and due to religious conflicts.

The historian Richard Bulliet found that it was only in the 10th century, when the Andalusi emirate became very powerful under Caliph Abd ar-Rahman III, that the number of Muslims became greater than Christians in al-Andalus. Before this, he believes, about half the population was Christian.

The growth of the Caliphate mainly happened through conversion and people joining the Muslim community, not so much through new immigrants. The remaining Mozarab community became smaller and less active.

However, relatively large Mozarab communities still existed until the end of the taifa kingdoms (small Muslim states). There were several Christian churches in Toledo when Christians took the city in 1085. Many documents in Arabic about the Mozarabs of Toledo still exist. A significant Mozarab group was also found in Valencia during the time of El Cid. The memoirs of the emir of Granada also show that a large Christian population lived in parts of the Málaga region in the late 11th century. A Mozarab community existed in Seville until Christians reconquered it in 1248, although many Mozarabs had fled north during the 12th century due to persecution by the Almoravids.

Rules and Challenges for Mozarabs

Christians did not have the same rights as Muslims under Islamic rule. Their initial protections, which were quite broad, slowly became fewer. They could still practice their religion privately, but their cultural freedom was reduced. Mozarabs gradually lost status, but they kept their culture and stayed in touch with the Christian world.

In the years after the conquest, Muslim rulers made new laws that were clearly unfair to dhimmi. Building new churches and ringing church bells were eventually forbidden. However, in the mid-9th century, there were still at least four Christian churches and nine monasteries in and around Córdoba. Their existence, however, became uncertain.

Mozarabs were generally tolerated as dhimmi and valued taxpayers. No Mozarab was sentenced to death until Christian leaders like Eulogius of Córdoba (executed in 859) and Alvaro of Córdoba began to openly challenge Muslim rule by insulting Muhammad and criticizing Islam. Eulogius opposed the Arabization of Christians and called for a purer Christian culture without Moorish influences. He led a revolt in Córdoba where Christians chose to become martyrs to protest Muslim rule.

However, historian Kenneth Baxter Wolf believes Eulogius was not the cause of these persecutions, but rather someone who wrote about the martyrs. Other records show a few Christians were executed in the late 9th and early 10th centuries. For example, a boy named Pelagius was executed in 925 for refusing to convert to Islam.

Eulogius's writings, which recorded the stories of the Córdoba martyrs (851–859), encouraged Christians to defy Muslim authorities and seek martyrdom. These Christians were different from earlier Visigothic Christians who had been advised by their bishop to be tolerant of Muslim authorities. By the mid-9th century, Christians felt increasingly isolated. They couldn't build new churches or ring bells, and they were excluded from most important political, military, or social positions. They also faced many other insults as unequal citizens under Islamic law. The Córdoba martyrs show a clear Christian opposition to the pressure from Islam, as they resisted conversion and absorption into Muslim culture.

The first official response to the Córdoba martyrs was to arrest and imprison Christian leaders. Towards the end of the martyrs' decade, Eulogius's writings mention the closing of Christian monasteries, which Muslims saw as places of disruptive fanaticism.

As the Reconquista advanced, Mozarabs moved into the Christian kingdoms, where kings gave special benefits to those who settled in frontier lands. They also fled north to the Frankish kingdom during times of persecution.

Many Mozarabs settled in the Ebro valley. King Alfonso VI of Castile encouraged Mozarab settlers by promising them land and rewards. The Anglo-Norman historian Orderic Vitalis wrote that Alfonso sent about 10,000 Mozarabs to settle on the Ebro. Mozarabs were rare in cities like Tudela or Zaragossa, but more common in places like Calahorra, which the Kingdom of Navarre conquered in 1045.

Mozarab Language and Culture

During the early development of Romance languages in Iberia, a group of related dialects was spoken in Muslim areas by the general population. These dialects are now known as the Mozarabic language. There was no single standard Mozarabic language.

This old Romance language was first written down in the form of short poems called kharjas within Arabic and Hebrew songs called muwashshahs. Since they were written using Arabic and Hebrew alphabets, their vowels have had to be reconstructed by scholars.

Mozarabic had a big impact on the development of Portuguese, Spanish, and Catalan, giving them many words from Andalusi Arabic. The movement of Mozarabs northward explains why Arabic place names are found in areas where Muslims did not stay for long.

The formal language of Mozarabs continued to be Latin. However, as time passed, young Mozarabs studied and became very good at Arabic. The widespread use of Arabic by the Moorish conquerors led the Christian writer Petrus Alvarus of Córdoba to complain about the decline of spoken Latin among local Christians.

Mozarabs often used Arabic-style names, showing that they adopted parts of Arab-language Islamic culture. They used names like Zaheid ibn Zafar or Ibn Gharsiya (Garcia) even in Christian settings. This shows they had truly adapted, and their Arabic names were not just aliases. On the other hand, some Christian names like Lope and Fortun entered the local Arabic language.

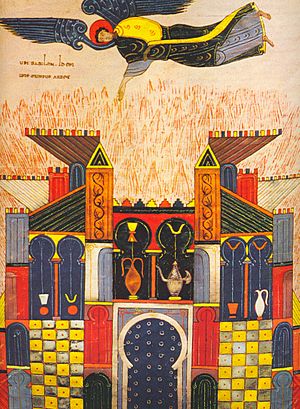

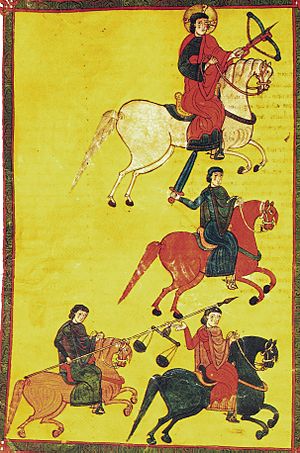

Mozarab Art and Religion

There are few remaining Christian scholarly writings from Muslim Iberia. What we have in Arabic are translations of the Gospels and Psalms, writings that criticized Islam, and a translation of a church history. There are also Latin writings, which remained the language used in church services.

Muslims in al-Andalus borrowed some cultural elements from Mozarabs. For example, Muslims adopted the Christian solar calendar and holidays, which was unique to al-Andalus. The Islamic lunar calendar was supplemented by the local solar calendar, which was more useful for farming and navigation. Muslims sometimes celebrated traditional Christian holidays, even with the support of their leaders, although religious scholars generally opposed this.

In the early days of Muslim rule in Iberia, there was a lot of interaction between the two communities. This is shown by shared cemeteries and churches, coins with both languages, and the continuation of old Roman pottery styles. Unlike other parts of the Muslim world, the conquerors in Iberia settled in existing towns, not in isolated military camps. This led to more contact with the local people.

Arab and Berber immigrants, though limited in number, brought new farming and water technologies, new crafts, and shipbuilding techniques from the Middle East. They also brought Arabic culture, including advanced learning and science. The emir of Córdoba, Abd ar-Rahman I, allowed the Arab political and military leaders to farm, which further encouraged economic and cultural contact. Also, marriages between foreigners and natives, and daily interactions in business and social life, quickly led to cultural blending.

The unique features of Mozarabic culture became more noticeable. However, Christian women often married Muslim men, and their children were raised as Muslims. Even within Mozarab families, legal divorce eventually followed Islamic practices. The way clergy were ordained also changed, moving away from traditional church rules.

Some Christian leaders, like Álvaro and Eulogius of Córdoba, were upset by how Christians were treated. They began to encourage public declarations of faith to strengthen the Christian community and protest Islamic laws they saw as unfair. Eulogius wrote stories about martyrs during this time.

Forty-eight Christians (mostly monks), known as the Martyrs of Córdoba, were executed between 850 and 859 for publicly stating their Christian beliefs. Under Muslim rule, non-Muslims (dhimmi) were not allowed to speak about their faith to Muslims, and doing so could lead to death.

Historians point out that the martyrs had different reasons for their actions, but many were protesting against the process of assimilation and wanted to assert their Christian identity.

The Mozarab population was severely affected by the worsening relations between Christians and Muslims during the Almoravid period. In 1099, the main Mozarab church in Granada was destroyed by order of the Almoravid emir, Yusuf ibn Tashfin.

Mozarabs remained separate from the influence of French Catholic religious groups like the Cistercians, who were very influential in northern Christian Iberia. Mozarabs kept their old Visigothic church service, also known as the Mozarabic Rite. However, the Christian kingdoms in the north changed to the Latin Rite and appointed northern bishops for the reconquered areas. Today, the Mozarabic Rite is still used daily in the Mozarab Chapel of the Cathedral of Toledo, thanks to a special permission from the Pope. A Mozarab brotherhood is still active in Toledo.

In 1080, Pope Gregory VII called a council that decided to unify the Latin rite across all Christian lands. When Toledo was reconquered in 1085, there was an attempt to bring back the Roman Catholic practices. However, the people of Toledo resisted so much that the king refused to enforce it. In 1101, he created the "Fuero (Code of laws) of the Mozarabs", which gave them special rights. This law applied only to the Castilians, Mozarabs, and Franks in the city.

King Alfonso VI of Castile was under constant pressure from his wives, who were devout Catholics, to get rid of the Mozarabic Rite. A popular story says that Alfonso VI put the Mozarab liturgy and the Roman Catholic liturgy to a test by fire, but the Catholic rite won. So, the Mozarab liturgy was supposedly abolished in 1086. However, the Mozarabic Chapel in the Cathedral of Toledo still uses the Mozarabic Rite and its music.

In 1126, many Mozarabs were forced to leave for North Africa by the Almoravids. Other Mozarabs fled to Northern Iberia. This marked the end of Mozarabic culture in al-Andalus. For a while, Mozarabs in both North Africa and Northern Iberia managed to keep their separate cultural identity. However, in North Africa, they eventually became Muslim.

Over the 12th and 13th centuries, Mozarab farmers became poorer as more land came under the control of powerful nobles and church groups. These church groups, influenced by the Benedictine bishop of Cluny and the Archbishop of Toledo Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada, promoted a policy of separation based on religious nationalism. Jiménez de Rada even suggested that the word Mozarab came from Mixti Arabi (mixed Arabs), implying that they were "contaminated" by Muslim customs.

In Toledo, King Alfonso VI of Castile did not recognize Mozarabs as a separate legal group. This led to their steady decline and eventual absorption into the general community by the end of the 15th century. As a result, Mozarabic culture was almost lost. Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros, recognizing the historical and religious value of the Mozarabic liturgy, worked to ensure its survival. He collected all the old texts, had them studied, and in 1502, the Mozarabic Missal (prayer book) and Breviary (book of daily prayers) were printed. This helped revitalize the faith, and a chapel with its own priests was set up in the cathedral, which still exists today.

The Mozarab Missal of Silos is the oldest Western manuscript written on paper, from the 11th century. The Mozarab community in Toledo continues to thrive today, with about 1,300 families whose family histories can be traced back to the ancient Mozarabs.

How Many Mozarabs Lived in Al-Andalus?

There is a long-standing debate about how many Mozarabs lived in al-Andalus. Some historians believe that Mozarabs were always the majority of the population, continuing a long history of Latin-speaking Christians. Others argue that the Christian population was relatively small in Muslim-ruled areas.

Those who believe Mozarabs were the majority often refer to the work of Francisco Javier Simonet, whose books supported the idea that the native Christian community in al-Andalus made up most of the population. However, other historians argue that Simonet and earlier scholars did not use sources correctly, and there isn't enough clear historical evidence to say for sure what the ethnic makeup of al-Andalus society was. According to scholar Josephine Labanyi, by the end of the 11th century, there were about 75,000 Christians in the Emirate of Granada, which was roughly 15% of the population of Islamic Iberia.

See also

In Spanish: Mozárabe para niños

In Spanish: Mozárabe para niños

- Mozarabic art and architecture

- Musta'arabi Jews

- Muwallad

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |