Mumia Abu-Jamal facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mumia Abu-Jamal

|

|

|---|---|

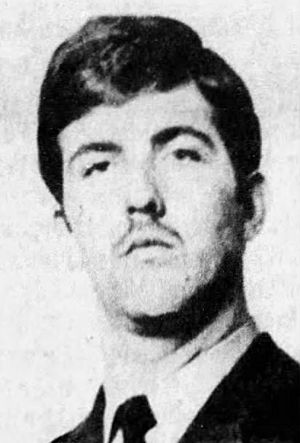

Abu-Jamal c. 1980

|

|

| Born |

Wesley Cook

April 24, 1954 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.

|

| Occupation | Activist, journalist |

| Criminal status | Incarcerated |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 8 |

| Conviction(s) | First degree murder |

| Criminal penalty | Death; commuted to life imprisonment |

Mumia Abu-Jamal (born Wesley Cook; April 24, 1954) is an American activist and journalist. He was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death in 1982 for the 1981 killing of Philadelphia police officer Daniel Faulkner. While in prison, he wrote and shared his thoughts on the justice system in the United States.

After many appeals, a federal court changed his death sentence. In 2011, prosecutors agreed to a sentence of life in prison without the chance of being released early. He joined the regular prison population in early 2012.

Abu-Jamal became involved with the Black Panther Party at age 14 in 1968. He was a member until October 1970. After leaving the party, he finished high school and became a radio reporter. He was also president of the Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists from 1978 to 1980. He supported MOVE, a group based in Philadelphia, and reported on a 1978 event where a police officer was killed.

Since 1982, many people have questioned if Abu-Jamal's trial was fair. Some believe he is innocent, and many were against his death sentence. However, Officer Faulkner's family, politicians, and law enforcement groups believe his trial was fair, he was clearly guilty, and his death sentence was right.

When his death sentence was changed in 2001, The New York Times called him "perhaps the world's best-known death-row inmate." While in prison, Abu-Jamal has published books and articles about social and political topics. His first book, Live from Death Row, came out in 1995.

Contents

Early Life and Activism

Mumia Abu-Jamal was born Wesley Cook in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He grew up there with his younger brother, William. They went to public schools in their neighborhood. In 1968, when he was 14, a high school teacher suggested students use African or Arabic names for class. The teacher gave Cook the name "Mumia." Abu-Jamal says "Mumia" means "Prince" and was the name of Kenyan anti-colonial leaders.

Joining the Black Panthers

Abu-Jamal said he joined the Black Panther Party at 14 after being beaten by some people and a police officer. This happened when he tried to stop a rally for George Wallace, a former governor of Alabama who had racist views. After this, he helped start the Philadelphia branch of the Black Panther Party. He became the "Lieutenant of Information," which meant he was in charge of writing news and information for the group. He left high school and lived at the party's headquarters.

He spent time in New York City and Oakland, California, working with other Black Panther members. He was part of the party from May 1969 to October 1970. During this time, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) watched him illegally as part of a program called COINTELPRO. This program aimed to cause problems within Black activist groups.

Education and Family Life

After leaving the Black Panthers, Abu-Jamal went back to his old high school. He was suspended for handing out papers that called for "black revolutionary student power." He also led protests to change the school's name to Malcolm X High.

He later earned his GED certificate. He then studied for a short time at Goddard College in Vermont before returning to Philadelphia.

Family Life

Wesley Cook changed his last name to Abu-Jamal, which means "father of Jamal" in Arabic, after his first child, Jamal, was born on July 18, 1971. He married Jamal's mother, Biba, in 1973, but they divorced later. Their daughter, Lateefa, was born soon after their wedding.

In 1977, Abu-Jamal married his second wife, Marilyn, also known as "Peachie." Their son, Mazi, was born in early 1978. By 1981, Abu-Jamal had divorced Peachie and married his third wife, Wadiya. Wadiya passed away on December 27, 2022.

Journalism Career

By 1975, Abu-Jamal was working in radio news. He started at Temple University's WRTI and then moved to commercial radio stations. He worked at WHAT in 1975 and hosted a weekly show at WCAU-FM in 1978. He also worked briefly at WPEN.

From 1979 to 1981, he worked for National Public Radio (NPR) at WHYY. The station asked him to leave because they felt he wasn't objective enough in his news reporting. As a radio journalist, Abu-Jamal was known for covering the MOVE group in West Philadelphia's Powelton Village. He reported on the trial of the "MOVE Nine" who were found guilty in the death of police officer James Ramp.

Abu-Jamal interviewed famous people like Julius Erving, Bob Marley, and Alex Haley. He was also elected president of the Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists.

In December 1981, Abu-Jamal was working as a taxicab driver in Philadelphia a couple of nights a week to earn more money. He was also working part-time as a reporter for WDAS, a radio station focused on African American listeners.

Officer Faulkner's Death and Trial

On December 9, 1981, at about 3:55 AM, Philadelphia police officer Daniel Faulkner stopped a car driven by William Cook, Abu-Jamal's younger brother. This happened near 13th and Locust Streets in Philadelphia. Officer Faulkner and Cook got into a fight. Abu-Jamal, who was driving his taxi nearby, saw the fight. He parked his cab and ran across the street toward his brother's car. Officer Faulkner was shot and died at the scene. Abu-Jamal was also shot in the stomach.

Arrest and Trial

Police arrived and arrested Abu-Jamal. A revolver with five used cartridges was found next to him. He was wearing a shoulder holster. He was taken to Thomas Jefferson University Hospital for treatment. After that, he was taken to Police Headquarters and charged with the first-degree murder of Officer Faulkner.

Prosecution's Case

The prosecution called four witnesses to the court. Robert Chobert, a taxi driver, said he was parked behind Faulkner and identified Abu-Jamal as the shooter. Cynthia White said Abu-Jamal came from a nearby parking lot and shot Faulkner. Michael Scanlan, a driver, said he saw a man like Abu-Jamal run across the street and shoot Faulkner. Albert Magilton saw Faulkner stop Cook's car, but turned away before the shooting.

Two witnesses from the hospital where Abu-Jamal was treated also testified. Hospital security guard Priscilla Durham and police officer Garry Bell said Abu-Jamal made a statement in the hospital.

A .38 caliber revolver belonging to Abu-Jamal was found next to him at the scene. A police expert said that bullet fragments from Faulkner's body were consistent with the weapon.

Defense's Case

The defense argued that Abu-Jamal was innocent and that the prosecution's witnesses could not be trusted. The defense called nine witnesses who spoke about Abu-Jamal's good character. Poet Sonia Sanchez said he was seen by the black community as a "peaceful, genial man." Another defense witness, Dessie Hightower, said he saw a man running away shortly after the shooting, which led to a "running man theory" suggesting someone else might have been the shooter. Abu-Jamal did not testify in his own defense, nor did his brother, William Cook.

Verdict and Sentence

After three hours of discussion, the jury found Abu-Jamal guilty.

During the sentencing part of the trial, Abu-Jamal read a statement to the jury. He criticized his lawyer and claimed his rights had been "stolen" from him. He said he was innocent of the charges.

The jury decided unanimously to sentence Abu-Jamal to death.

Amnesty International has raised concerns about the trial. They noted that statements from his youth as an activist were used against him during sentencing. They also pointed out a history of police problems in Philadelphia, including false evidence. Amnesty International concluded that the trial did not meet basic international standards for fair trials and the use of the death penalty.

Appeals and Review

State Appeals

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania rejected his first appeal on March 6, 1989. The Supreme Court of the United States also refused to hear his case.

On June 1, 1995, Pennsylvania Governor Tom Ridge signed an order for Abu-Jamal's execution. However, the execution was stopped while Abu-Jamal continued to appeal in state courts. During these hearings, new witnesses were called. One witness, William "Dales" Singletary, claimed he saw the shooting and that the gunman was a passenger in Cook's car. However, the court found his story "not credible."

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court later ruled that all of Abu-Jamal's arguments, including claims that his lawyer was ineffective, had no merit. The U.S. Supreme Court again refused to hear his case in October 1999, allowing Governor Ridge to sign a second death warrant. This execution was also stopped as Abu-Jamal began to seek review in federal courts.

In 1999, a man named Arnold Beverly claimed that he and another person, not Mumia Abu-Jamal, shot Daniel Faulkner. He said it was a planned killing because Faulkner was interfering with illegal payments to corrupt police. Abu-Jamal's defense team was divided on whether to use Beverly's statement, with some finding it unbelievable.

In 2008, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court rejected another request from Abu-Jamal for a hearing. This request was based on claims that trial witnesses had lied. The court said he had waited too long to file the appeal.

On March 26, 2012, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court rejected his appeal for a new trial. His defense had argued that some forensic evidence used in the original trial was unreliable. This was reported as Abu-Jamal's last legal appeal in state court.

In April 2018, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled that Abu-Jamal would not immediately get another appeal. His defense argued that former Pennsylvania Supreme Court Chief Justice Ronald D. Castille should not have been involved in the 2012 appeal decision. This was because Castille had been the Philadelphia District Attorney during Abu-Jamal's 1989 appeal. A letter from Castille in 1990, urging the governor to sign execution orders for police killers, was cited as a reason to suspect his bias.

In April 2019, Philadelphia's current District Attorney Larry Krasner agreed not to oppose a new appeal effort for Abu-Jamal. However, in March 2023, a Philadelphia judge blocked this latest appeal.

Federal Court Ruling

In 2001, Judge William H. Yohn, Jr. of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania upheld Abu-Jamal's conviction. However, he changed the death sentence on December 18, 2001. He said there were problems with how the jury was instructed during the sentencing phase of the trial. He ordered Pennsylvania to hold new sentencing proceedings.

Both sides appealed this ruling. Officer Faulkner's widow, Maureen, said the decision would allow Abu-Jamal, whom she called a "remorseless, hate-filled killer," to "enjoy the pleasures that come from simply being alive."

Federal Appeals

On December 6, 2005, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals agreed to review four issues from the District Court's ruling. These included questions about the jury instructions, possible racial bias in jury selection, whether the prosecutor improperly influenced jurors, and if the judge in the post-conviction hearings showed bias.

The Third Circuit Court heard arguments on May 17, 2007. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania wanted the death sentence put back in place. They argued that the judge's ruling was wrong. Abu-Jamal's lawyers argued that he did not get a fair trial because of racial bias in the jury. They noted that the prosecution used many of its challenges to remove potential Black jurors. A former court reporter claimed she overheard the judge make a biased comment about Abu-Jamal, which the judge denied.

On March 27, 2008, the appeals court upheld the 2001 decision to change the death sentence. On April 6, 2009, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear Abu-Jamal's appeal, meaning his conviction stood.

On January 19, 2010, the Supreme Court ordered the appeals court to reconsider its decision about the death penalty. On April 26, 2011, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals again decided to remove the death sentence because the jury instructions were confusing. The Supreme Court again declined to hear the case in October.

Death Penalty Removed

On December 7, 2011, Philadelphia District Attorney R. Seth Williams announced that prosecutors would no longer seek the death penalty for Abu-Jamal. This decision had the support of Officer Faulkner's family. Abu-Jamal would instead serve a sentence of life in prison without the chance of being released early. This sentence was confirmed by the Superior Court of Pennsylvania on July 9, 2013.

Maureen Faulkner, Officer Faulkner's widow, said she did not want to go through the pain of another trial. She understood it would be very hard to present the case again after 30 years, especially since several key witnesses had passed away.

Life as a Prisoner

In 1991, Abu-Jamal published an essay in the Yale Law Journal about the death penalty and his experiences in prison. In May 1994, NPR's All Things Considered program planned for Abu-Jamal to give monthly three-minute talks on crime and punishment. However, these plans were canceled after groups like the Fraternal Order of Police and Senator Bob Dole spoke out against them. Abu-Jamal sued NPR, but a federal judge dismissed the case. His talks were later published in May 1995 as part of his first book, Live from Death Row.

In 1996, he earned a B.A. degree through correspondence classes from Goddard College. He has been invited to give commencement speeches at several colleges, participating through recordings. In 1999, he recorded a speech for Evergreen State College. In 2000, he recorded one for Antioch College. The now-closed New College of California School of Law gave him an honorary degree for his fight against the death penalty.

On October 5, 2014, he gave the commencement speech at Goddard College via a recording. This choice was controversial. Ten days later, the Pennsylvania legislature passed a new law called "Revictimization Relief." This law aimed to stop actions that cause "mental anguish" to crime victims. It was signed by Governor Tom Corbett. Many people thought this law was meant to control Abu-Jamal's writing and speaking, and that it would be challenged as a violation of free speech.

Abu-Jamal has been a regular commentator on an online broadcast sponsored by Prison Radio for many years. He also writes a regular column for Junge Welt, a newspaper in Germany. For almost ten years, he taught basic economics courses by mail to other prisoners around the world.

He has written and published several books:

- Live From Death Row (1995), a diary of his life on death row.

- All Things Censored (2000), a collection of essays about crime and punishment.

- Death Blossoms: Reflections from a Prisoner of Conscience (2003), where he explores religious ideas.

- We Want Freedom: A Life in the Black Panther Party (2004), a history of the Black Panthers that includes his own experiences and research.

In 1995, Abu-Jamal was put in solitary confinement for doing business that was against prison rules. After a 1996 HBO documentary about him, the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections banned recording equipment in state prisons.

In 1998, Abu-Jamal successfully argued in court that he had the right to write for money while in prison. The court also found that the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections had illegally opened his mail to see if he was earning money from his writing.

In August 1999, when Abu-Jamal began giving his radio talks live on the Pacifica Network's Democracy Now! program, prison staff cut his telephone wires. He was later allowed to continue his broadcasts, and hundreds of his talks have been aired on Pacifica Radio.

After his death sentence was changed, Abu-Jamal was sentenced to life in prison in December 2011. In late January 2012, he was moved from the isolation of death row to the general prison population at State Correctional Institution – Mahanoy.

In August 2015, his lawyers filed a lawsuit, saying he was not getting proper medical care for his serious health problems. In April 2021, he tested positive for COVID-19 and was scheduled for heart surgery.

In 2022, Brown University's John Hay Library acquired Abu-Jamal's personal papers. This collection is part of their effort to gather stories about mass incarceration. According to a Brown University archivist, it is the largest collection related to someone still in prison.

Public Support and Opposition

Many groups, including labor unions, politicians, educators, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, and human rights organizations like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, have expressed concerns about whether Abu-Jamal's trial was fair. Amnesty International does not say if Abu-Jamal is guilty or innocent, nor do they call him a political prisoner.

However, Daniel Faulkner's family, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the City of Philadelphia, politicians, and the Fraternal Order of Police continue to support the original trial and conviction. In August 1999, the Fraternal Order of Police called for people to stop buying from businesses that support Abu-Jamal.

Because of his writings, Abu-Jamal and his case have become well-known around the world. Some groups have called him a political prisoner. About 25 cities, including Montreal, Palermo, and Paris, have made him an honorary citizen.

In 2001, he received the Erich Mühsam Prize, which honors activism. In October 2002, he became an honorary member of a German political organization.

On April 29, 2006, a new road in the Parisian suburb of Saint-Denis was named Rue Mumia Abu-Jamal in his honor. In protest, U.S. Congressman Michael Fitzpatrick and Senator Rick Santorum introduced resolutions in the U.S. Congress condemning the decision. The House of Representatives voted 368–31 in favor of Fitzpatrick's resolution. In December 2006, the Republican Party in Philadelphia filed complaints in the French legal system against Paris and Saint-Denis. They accused the cities of "glorifying" Abu-Jamal.

In 2007, Officer Faulkner's widow co-wrote a book with Philadelphia radio journalist Michael Smerconish called Murdered by Mumia: A Life Sentence of Pain, Loss, and Injustice. The book shared her experiences and discussed evidence from Abu-Jamal's trial.

In early 2014, President Barack Obama nominated Debo Adegbile, a former lawyer for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, to lead the civil rights division of the Justice Department. He had worked on Abu-Jamal's case, and his nomination was rejected by the U.S. Senate because of this.

After Goddard College invited Abu-Jamal to give a recorded speech in 2014, and police unions protested, the Revictimization Relief Act was passed in Pennsylvania. This law allowed victims and prosecutors to sue if a person caused "mental anguish" by talking about their crime. However, the law was struck down in April 2015 because it was too broad and limited free speech.

On April 10, 2015, Marylin Zuniga, a teacher in Orange, New Jersey, was suspended without pay. She had asked her students to write cards to Abu-Jamal, who was ill in prison, without getting approval from the school or parents. Some parents and police leaders criticized her actions. However, some community members, parents, teachers, and professors supported Zuniga and spoke against her suspension. Many scholars and educators, including Noam Chomsky and Cornel West, signed a letter asking for her to be hired back. On May 13, 2015, the school board voted to dismiss Marylin Zuniga.

Written Works

- Beneath the Mountain: An Anti-Prison Reader, City Lights Publishers (2024), ISBN: 9780872869264

- Murder Incorporated - Dreaming of Empire: Book One (Empire, Genocide, and Manifest Destiny) (2018), Prison Radio, ISBN: 9780998960012, co-authored by Stephen Vittoria

- Have Black Lives Ever Mattered? City Lights Publishers (2017), ISBN: 9780872867383

- Writing on the Wall: Selected Prison Writings of Mumia Abu-Jamal, City Lights Publishers (2015), ISBN: 978-0872866751

- The Classroom and the Cell: Conversations on Black Life in America, Third World Press (2011), ISBN: 978-0883783375

- Jailhouse Lawyers: Prisoners Defending Prisoners v. the U.S.A., City Lights Publishers (2009), ISBN: 978-0872864696

- We Want Freedom: A Life in the Black Panther Party, South End Press (2008), ISBN: 978-0896087187

- Faith of Our Fathers: An Examination of the Spiritual Life of African and African-American People, Africa World Press (2003), ISBN: 978-1592210190

- All Things Censored, Seven Stories Press (2000), ISBN: 978-1583220221

- Death Blossoms: Reflections from a Prisoner of Conscience, Plough Publishing House (1997), ISBN: 978-0874860863

- Live from Death Row, Harper Perennial (1996), ISBN: 978-0380727667

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Mumia Abu-Jamal para niños

In Spanish: Mumia Abu-Jamal para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |