Naqsh-e Rostam facts for kids

|

نقش رستم

|

|

|

|

| Location | Marvdasht, Fars Province |

|---|---|

| Region | Iran |

| Coordinates | 29°59′20″N 52°52′29″E / 29.98889°N 52.87472°E |

| Type | Necropolis |

| History | |

| Periods | Achaemenid, Sassanid |

| Cultures | Persian |

| Management | Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization of Iran |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural styles | Persian |

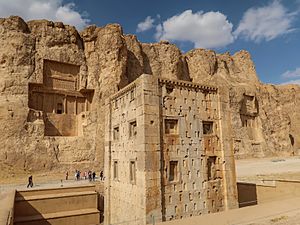

Naqsh-e Rostam (Persian: نقش رستم) is an amazing ancient site in Iran. It's about 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) northwest of Persepolis in Fars Province. This place is famous for its ancient rock reliefs, which are huge carvings made into the side of a cliff. These carvings come from two important periods in Persian history: the Achaemenid Empire and the Sassanid Empire.

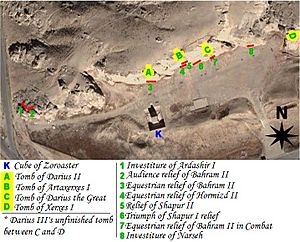

Naqsh-e Rostam was a special burial ground, or necropolis, for the Achaemenid dynasty (around 550–330 BC). Four large tombs are carved high into the cliff face. These tombs have cool architectural designs. Above their doorways, you can see large carvings. These carvings show the king being blessed by a god. Below them are rows of smaller figures bringing gifts, along with soldiers and officials. The size of the figures clearly shows their importance. The entrance to each tomb is in the middle of a cross-shaped design. Inside, there's a small room where the king's sarcophagus (a stone coffin) was placed.

Below these Achaemenid tombs, closer to the ground, are rock reliefs from the Sassanian kings. Some show kings meeting gods, while others show them in battle. One very famous carving shows the Sassanian king Shapur I on horseback. The Roman Emperor Valerian is bowing to him, showing he surrendered. Another emperor, Philip the Arab, holds Shapur's horse. The dead Emperor Gordian III lies beneath the horse. This carving celebrates the Battle of Edessa in 260 AD. In this battle, Valerian became the only Roman Emperor ever captured as a prisoner of war. This was a huge embarrassment for the Romans. By placing their carvings here, the Sassanids wanted to connect themselves to the glory of the older Achaemenid Empire.

Contents

Exploring Ancient Monuments

The oldest carving at Naqsh-e Rostam is from about 1000 BC. It's quite damaged, but you can still see a faint image of a man with unusual headwear. Experts think it's from the Elamite period. This carving was part of a bigger mural, but most of it was removed by order of Bahram II. The man with the unique cap gave the site its name, Naqsh-e Rostam, which means "Rustam Relief." Locals believed the carving showed the mythical hero Rustam.

Royal Achaemenid Tombs

Four tombs of Achaemenid kings are carved high up in the rock face. People sometimes call these tombs the Persian crosses because of the cross shape of their fronts. The entrance to each tomb is in the middle of this cross. It leads to a small room where the king's sarcophagus was kept. The horizontal part of each tomb's front is thought to be a copy of an entrance at Persepolis.

One tomb is clearly identified by an inscription as the tomb of Darius I (who ruled from about 522-486 BC). The inscription says, "a Parsi, the son of a Parsi, an Aryan, of Aryan family." The other three tombs are believed to belong to Xerxes I (about 486-465 BC), Artaxerxes I (about 465-424 BC), and Darius II (about 423-404 BC). The tombs are arranged from left to right as: Darius II, Artaxerxes I, Darius I, and Xerxes I. Matching the kings to their tombs is a bit of a guess, as the carved figures don't look like individual portraits.

There's also a fifth unfinished tomb. It might belong to Artaxerxes III, who ruled for only two years. But it's more likely for Darius III (about 336-330 BC), who was the last king of the Achaemenid dynasty. These tombs were robbed after Alexander the Great conquered the Achaemenid Empire.

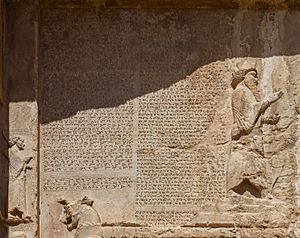

Darius I's Famous Inscription

An important inscription by Darius I, from around 490 BCE, is on the top left corner of his tomb's front. Scholars call it the "DNa inscription." It talks about Darius I's conquests and achievements. We don't know the exact date, but it's probably from the last ten years of his rule. Like other inscriptions by Darius, it lists the lands controlled by the Achaemenid Empire. This empire was the largest empire in ancient times. It stretched from Macedon and Thrace in Europe to Egypt in North Africa. It also included Babylon and Assyria in Mesopotamia, parts of Eurasia, Bactria in Central Asia, and even Gandhara and the Indus area in India. These areas were added during the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley.

| What the inscription says | Where it is |

|---|---|

|

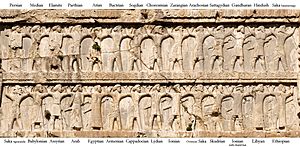

The people from different lands mentioned in the DNa inscription are also shown on the upper parts of all the tombs at Naqsh-e Rostam. One of the best preserved is on the tomb of Xerxes I.

|

Ka'ba-ye Zartosht: The Cube of Zoroaster

The Ka'ba-ye Zartosht (meaning "Cube of Zoroaster") is a square tower from the 5th century BC, built during the Achaemenid period. This building is a copy of a similar one at Pasargadae, called the "Prison of Solomon." It was likely built by Darius I (who ruled 521–486 BCE) when he moved to Persepolis, or possibly by Artaxerxes II (404–358 BCE) or Artaxerxes III (358–338 BCE). The building at Pasargadae is a few decades older. On the lower outside walls, there are four inscriptions from the Sasanian period, written in three languages. These are considered some of the most important inscriptions from that time.

People have different ideas about what the Ka'ba-ye Zartosht was used for.

Sassanid Rock Carvings

Seven large rock carvings at Naqsh-e Rostam show kings from the Sassanid period. They were made between about 225 and 310 AD. These carvings show scenes like kings being given their power and kings in battle.

Ardashir I: Becoming King (around 226–242 AD)

This carving shows Ardashir I, who founded the Sassanid Empire. He is receiving the ring of kingship from Ohrmazd, a god. In the inscription, Ardashir admits he broke his promise to Artabanus V, the ruler of the Arsacid Parthians, whom the Persians used to serve. But Ardashir says he did it because Ohrmazd wanted him to.

The word ērān (which is part of the word Iran) first appears in the inscriptions next to this carving of Ardashir I. In this inscription, the king calls himself "Ardashir, king of kings of the Iranians."

Shapur I's Great Victory (around 241–272 AD)

This is the most famous Sassanid rock carving. It shows Shapur I's victory over two Roman emperors, Valerian and Philip the Arab. Behind the king stands Kirtir, the mūbadān mūbad (meaning 'high priest'). He was the most powerful Zoroastrian priest in Iran at that time. A more detailed version of this carving can be found at Bishapur.

In an inscription, Shapur I says he controlled the land of the Kushans all the way to "Purushapura" (Peshawar). This suggests he ruled over Bactria and areas as far as the Hindu-Kush mountains, or even south of them.

I, the Mazda-worshipping lord, Shapur, king of kings of Iran and An-Iran… (I) am the Master of the Domain of Iran (Ērānšahr) and own the land of Persis, Parthian… Hindestan, the land of the Kushan up to the borders of Paškabur and up to Kash, Sughd, and Chachestan.

—Naqsh-e Rostam inscription of Shapur I

Bahram II's "Grandee" Carving (around 276–293 AD)

In this carving, King Bahram II is shown with a very large sword. On each side of him, figures face the king. On the left, there are five figures, possibly members of the king's family. Three of them wear crowns, showing they were royalty. On the right, there are three courtiers, and one might be Kartir. This carving is right next to Ardashir's investiture inscription. It partly replaced a much older carving that gave Naqsh-e Rostam its name.

Bahram II's Two Horseback Carvings (around 276–293 AD)

The first horseback carving is just below the fourth tomb (possibly Darius II's). It shows the king fighting a Roman enemy on horseback.

The second horseback carving is right below Darius I's tomb. It has two parts, an upper and a lower. In the upper part, the king seems to be forcing a Roman enemy, probably Roman emperor Carus, off his horse. In the lower part, the king is again fighting an enemy on horseback. This enemy wears a helmet shaped like an animal's head. People think this is the defeated Indo-Sassanian ruler Hormizd I Kushanshah. Both carvings show a dead enemy under the hooves of the king's horse.

Narseh Becomes King (around 293–303 AD)

In this carving, King Narseh is shown receiving the ring of kingship from a female figure. Many people think this figure is the goddess Aredvi Sura Anahita. However, the king isn't in a pose you'd expect when meeting a god. So, it's more likely that the woman is a relative, perhaps Queen Shapurdukhtak of Sakastan.

Hormizd II's Horseback Carving (around 303–309 AD)

This carving is below tomb 3 (possibly Artaxerxes I's tomb). It shows Hormizd II forcing an enemy (perhaps Papak of Armenia) off his horse. Just above this carving and below the tomb is a badly damaged carving. It seems to show Shapur II (around 309–379 AD) with his courtiers.

Discovering the Past: Archaeology

In 1923, a German archaeologist named Ernst Herzfeld made copies of the inscriptions on Darius I's tomb. Since 1946, these copies have been kept in the archives of the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC.

Naqsh-e Rostam was excavated (dug up by archaeologists) for several seasons between 1936 and 1939. This work was done by a team from the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, led by Erich Schmidt.

Images for kids

-

A drawing of Naqsh-e Rostam from the 1600s, by Jean Chardin.

See also

In Spanish: Naqsh-e Rostam para niños

In Spanish: Naqsh-e Rostam para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |