New Zealand mud snail facts for kids

Quick facts for kids New Zealand mudsnail |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| right side view of Potamopyrgus antipodarum | |

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Subclass: | Caenogastropoda |

| Order: | Littorinimorpha |

| Family: | Tateidae |

| Genus: | Potamopyrgus |

| Species: |

P. antipodarum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Potamopyrgus antipodarum (J. E. Gray, 1843)

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

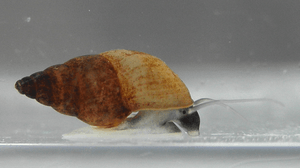

The New Zealand mudsnail (Potamopyrgus antipodarum) is a very tiny freshwater snail. It has a gill to breathe underwater and a special "lid" called an operculum that can seal its shell opening. This water snail is part of the family called Tateidae.

This snail originally comes from New Zealand. You can find it all over that country. However, it has traveled to many other places around the world. In these new places, it often becomes an invasive species. This means it spreads quickly and can cause problems because there can be so many of them.

Contents

Shell Features

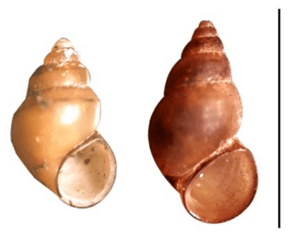

The shell of the New Zealand mudsnail is long and spirals to the right. It usually has 7 to 8 turns, called whorls, with deep lines between them. The shells can be gray, dark brown, or light brown.

On average, the shell is about 5 millimeters (about 0.2 inches) tall. The biggest ones can be about 12 millimeters (about 0.5 inches) tall. In places like the Great Lakes in the U.S., they are usually smaller, around 4–6 millimeters long.

The snail has a thin, tough "lid" called an operculum. This lid can close off the shell's opening, protecting the snail. The opening of the shell is oval-shaped. Some mudsnails have a ridge, like a small keel, in the middle of each whorl. Others have tiny spines on their shells. These spines help protect them from animals that might try to eat them.

Where They Live

This snail first lived only in New Zealand. It was found in freshwater streams and lakes there.

Now, it has spread widely and lives in many other places. It is considered an invasive species in these new areas. It likely spread because of people accidentally moving them.

Spreading to Europe

The New Zealand mudsnail was first found in Ireland around 1837. Since then, it has spread across most of Europe. It is thought to be one of the worst non-native species in Europe.

It can be found in many European countries, including England (since 1859), Germany, Poland, Russia, Italy, and the Czech Republic (since 1981).

Spreading to the United States

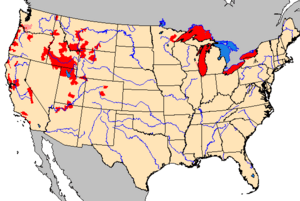

The New Zealand mudsnail was first found in the United States in Idaho in 1987. Since then, it has spread to many rivers and lakes in the western U.S., including areas around Yellowstone National Park.

Scientists believe the snails might have been carried in water used to transport live fish. They also could have spread through water in ship ballast tanks or on dirty fishing and boating gear.

In the U.S., the New Zealand mudsnail has no natural enemies or diseases that keep its numbers in check. Because of this, it has become an invasive species. In some rivers, there can be more than 300,000 snails in just one square meter! They can outcompete native snails and water insects for food. This means there's less food for fish, which then causes fish populations to drop.

These mudsnails are very tough. They can live for a whole day without water. They can even survive for up to 50 days on a damp surface. This makes it easy for them to be moved from one body of water to another on fishing equipment. They can even survive passing through the stomachs of fish and birds!

The snails have spread to many western states, including Wyoming, California, Nevada, Oregon, Montana, and Colorado. Officials are trying to slow their spread. They tell people to check their gear for snails and clean it with bleach or heat. Some rivers have even been closed to fishing to stop the snails from spreading.

In the U.S., the snails are usually smaller than in New Zealand. They are often only about 6 millimeters (0.25 inches) long. This small size makes them easy to miss when cleaning gear.

In 1991, the New Zealand mudsnail was found in Lake Ontario. Now, it has spread to four of the five Great Lakes. The snails in the Great Lakes are a different type from those in the western states. They likely came to the U.S. indirectly through Europe.

In 2010, the Los Angeles Times reported that the snails had infested streams in the Santa Monica Mountains. This was a big problem for native animals, like the endangered steelhead fish. The snails spread quickly, possibly carried by people working or volunteering in the streams.

In Colorado, the snails have been in Boulder Creek since 2004. They were found in Dry Creek in 2010. These creeks have been closed to help stop the snails from spreading further.

Ecology

Habitat

The New Zealand mudsnail can live in many different places. It does well in water with lots of mud and in areas where the water has been disturbed. It also likes places with lots of nutrients, which helps green algae grow.

You can find them among water plants. They prefer calm areas in lakes or slow-moving streams where the bottom is muddy and has lots of dead plants. However, they can also live in fast-moving water by digging into the mud.

In the Great Lakes, these snails can reach very high numbers, up to 5,600 snails in one square meter! They are found at depths of 4 to 45 meters on muddy and sandy bottoms.

This snail can live in both fresh water and slightly salty water, called brackish water. It can feed, grow, and reproduce in water with some salt, and can even handle very salty water for short times. It can also survive in temperatures from 0 to 34 degrees Celsius (32 to 93 degrees Fahrenheit).

Feeding Habits

The New Zealand mudsnail is a night-time eater. It scrapes food off surfaces. It eats dead plant and animal bits, algae growing on plants and rocks, and tiny single-celled organisms called diatoms.

Life Cycle and Reproduction

The New Zealand mudsnail reproduces in a special way. It is ovoviviparous, meaning the eggs hatch inside the mother, and she gives birth to live young. It is also parthenogenic. This means the females can reproduce without a male! They are "born with developing embryos" inside them.

In New Zealand, there are both males and females, and they can reproduce sexually. But in North America, almost all the snails are genetically identical females that reproduce asexually.

Because they can reproduce both sexually and asexually, these snails are studied to understand why sexual reproduction is important. Asexual reproduction allows all females to have babies without needing to find a mate. However, the babies are all exact copies, like clones. This means they all have the same weaknesses to diseases and parasites. If a parasite can infect one, it can infect them all.

Sexual reproduction mixes up genes, giving the babies different ways to fight off parasites. This means a parasite can't easily wipe out the whole population. New Zealand mudsnails often get infected by tiny worm-like parasites called trematodes. These parasites are common in shallow water. In shallow water, sexual reproduction is more common because it helps snails fight off these parasites. In deeper water, where parasites are rare, asexual reproduction is more common because it's easier and faster.

Each female can produce between 20 and 120 tiny snails at a time. A single snail can produce about 230 young in a year. They reproduce mostly in spring and summer. Their fast reproduction rate helps them spread quickly in new places. The most snails ever found in one place was in Lake Zurich in Switzerland. There, the snails took over the whole lake in seven years, with 800,000 snails in just one square meter!

Parasites and Other Relationships

In their home country of New Zealand, parasites help control the mudsnail population by making many snails unable to reproduce. But in other parts of the world, without these parasites, the snails become an invasive pest.

New Zealand mudsnails can survive passing through the stomachs of fish and birds. This means these animals can accidentally carry the snails to new places.

The snails can also float on their own or on mats of algae. They can even move upstream in rivers by crawling against the current. They can sense the smell of fish that might eat them. When they do, they hide under rocks to stay safe.

Images for kids