Palestinian wine facts for kids

People have been making wine in the region of Palestine for thousands of years. Wine was very important for many reasons. It was used in Jewish religious ceremonies, for social gatherings, as part of people's food, and even as medicine. During the time of the Byzantine Empire, a lot of wine was made and sold to other countries around the Mediterranean Sea. Wine making by Christians slowed down after the Islamic conquest in the 600s. It started up again for a short time when Frankish Christians settled there during the Crusades in the 1100s. Jewish people kept growing grapevines into the late 1400s and during the Ottoman Empire. The first modern wineries were built by German settlers in Sarona (now part of Tel Aviv, Israel) in 1874-1875. Jewish people also started a winery in Rishon LeZion (also in Israel) in 1882.

Contents

Ancient Times: Wine in the Holy Land

Ancient Egypt bought wine from the land of Canaan (which included parts of Palestine) as far back as the Early and Late Bronze Age. Many wine jugs from Canaan have been found in royal tombs in Abydos, Egypt, dating back to around 3100 BCE. This shows that wine from Canaan was a big part of important feasts for kings and queens. People in the ancient Near East often used wine in their religious offerings. Egyptians from the 1400s BCE even said that wine from Canaan was "more abundant than water." Later, wine was also used in Jewish religious rituals to go along with other offerings.

Roman and Byzantine Eras: Wine for Trade

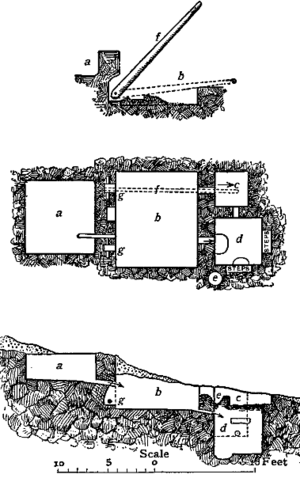

Grapevines were one of the three main crops grown in Palestine during the Roman and Byzantine periods. Many old wine-making places have been found. Wine was made all over the region, from the rich plains in the north to the dry areas of the Negev desert. In Akhziv, a huge wine press that could hold 59,000 liters was found, dating back to the 300s CE.

Archaeology shows that wine production greatly increased in the early Byzantine period. Most of the large wine presses are from this time. The wise teachers of the Talmud wrote a lot about making and selling wine, and they made many religious rules about it. Even though the Talmud says that "the wine of Tyre was cheaper than Palestinian wine," it does not mention wine being sent to other countries. However, other writings from the Byzantine period show that this did happen.

Around the mid-300s, a writer said that "Ashkelon and Gaza…export the best wine to all Syria and Egypt." Many transport jars, called amphorae, have been found at different places around the Mediterranean Sea. They have been found in harbors and in shipwrecks off the coasts of Cyprus, Greece, and Asia Minor.

Important international trade in Palestinian wine began in the early 400s and lasted for about 250 years. Many Palestinian amphorae have been found in other countries. They show that Palestinian wines were sent as far as Spain, Gaul (modern-day France), and even Wales. It is believed that a common type of pottery jar, called the Palestinian Bag Jar, was used to carry white Palestinian wine when it was exported. John the Merciful, who lived in the 600s, was said to have loved the smell of the expensive Palestinian wine he was offered in Alexandria. Since it came from the land of the Bible, Christian priests liked to use Palestinian wine for their religious ceremonies, like the Eucharist.

Islamic and Crusader Eras: Changes in Wine Making

In the late 600s, the Western Church stopped using Palestinian wine. This was probably because it became too expensive or hard to get after the Arab invasion. During the first centuries of Islamic rule, wine continued to be made. It was not only enjoyed by Christians and Jews, but also by some Muslims. Some Muslims even wrote "wine poems" to celebrate it.

In later periods of Muslim rule, wine making became less common. This was because growing grapevines was sometimes limited or forbidden by Islamic religious law. An old wine press found in Rechovot (in Israel) shows that it stopped being used for wine in the 700s-800s. Instead, it was used as a rubbish pit.

When the Crusaders took control of Palestine in the 1100s, there was a high demand for wine from the Latin Church and the Frankish city dwellers. This made growing grapevines a good business again. The Franks set up settlements where they grew grapes. Even after they left their colony at Ramathes (modern-day Al-Ram) in 1187, it continued to make wine until the late 1400s. A traveler named Meshullam of Volterra (in 1481) found that in Gaza, only Jewish people were involved in making wine.

Ottoman and British Mandate Eras: Modern Wine Begins

1500s–1700s: Rules and Toleration

In the 1500s, the Ottoman Empire rulers did not allow Muslims to drink wine. However, they allowed it to be sold to non-Muslims. Later, in 1754, an Ottoman rule was made to prevent people from acting improperly due to drinking. This rule stopped Jews from selling wine to Muslims or Christians.

1800s–1900s: New Wineries Emerge

The mid-1800s saw a quick increase in grape growing, mostly by Jewish farmers. Rabbi Isaac Schorr started a modern winery in Jerusalem in 1848. In the same year, a Jewish community representative on a trip to Jamaica brought 32 barrels of wine from the Land of Israel. The money from selling this wine helped Jewish people back in Palestine. In 1870, Rabbi Abraham Tepperberg founded the Efrat winery in the Old City of Jerusalem. Also, the Jewish Agricultural School at Mikveh Israel began growing the first European types of grapevines.

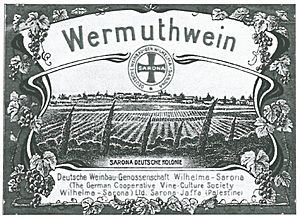

German settlers called Templers started a community in Sarona in 1871. They chose grape growing as one of their main businesses. They built the first wine factory and modern wine cellars in Palestine. In 1874-1875, a group of wine makers formed a co-operative, and the first winery and cellars were built. A second winery was built in 1890, and wine began to be sent to Germany. By the late 1890s, there were 150 hectares of vineyards producing 4000 hectoliters (about 106,000 US gallons) of wine each year.

The new Templer settlement of Wilhelma joined the wine co-operative in 1902. Wine production at Sarona and Wilhelma continued during the British Mandate, with most sales going to southern Germany.

Jewish grape growing on a large scale for business began in 1882 with the opening of the Carmel Winery in Rishon LeZion. This was thanks to Baron Edmond James de Rothschild, who spent a lot of money to help develop grape growing and wine making in Palestine. American grapevines were brought in, and French grape shoots were attached to them. French experts came to help with the project. A large wine cellar was built, and modern machines were installed. However, Rothschild had to buy Palestinian wine at higher prices than usual to keep the business going.

At that time, kosher red wine was often sweet and not very fancy. British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli once said it tasted "not so much like wine, but more like what I expect to receive from my doctor as a remedy for a bad winter cough."

Other wineries started during this time and are still working today. These include the Cremisan Monastery, near Bethlehem, where Italian monks have been making wine since 1885. Also, the Latrun Monastery, where French monks began making wine in 1899. The area of vineyards owned by Jewish people grew from about 11,000 dunam in 1890 to around 26,000 dunam by 1900.

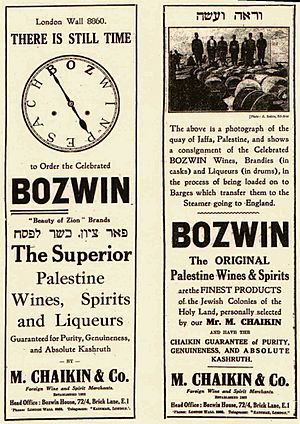

In 1883, a company called M. Chaikin & Co. was started in the United Kingdom. It imported wine made in Petah Tikva called "Bozwin" (Beauty of Zion Wine). In 1898, another London company, the Palestine Wine Trading Co., was created. A "wine-war" happened between the two British companies, as both claimed to be the only ones who could import kosher Palestinian wine. Today, Palwin, which means "Palestine wine," is Israel's oldest brand, making 100,000 bottles every year. Palestinian wine won a gold medal at the Paris Exposition of 1900.

By 1903, wine was Palestine's third-largest export and continued to be a very important product for the economy.

Before World War I, the United States and Russia were the biggest buyers of Palestinian wine. Because of the war and the start of Prohibition in the United States in 1920, the market for wine dropped a lot. In the early 1920s, American Orthodox Jewish groups tried to get permission to import Palestinian wine for religious use during the Passover holiday, but they were not successful at first. Large amounts of unsold wine were used to make jam and concentrated grape juice for European markets.

In December 1926, the US prohibition department allowed the import of Palestinian kosher wine. Jewish people could get this wine through the rabbis of their congregations. When Prohibition ended in 1933, Rothschild winery signed a contract with an American company. This contract was for importing one million bottles of wines and spirits from Palestine over three years. This was a very big deal, worth $15,000,000. The contract was later changed to allow for the import of 3,000,000 bottles in 1934 alone.

Early 1934 saw a 30% increase in the export of Palestinian wine. Most of it was sent to the US, which had been sending "urgent requests for tens of thousands of bottles of Jewish wine." To meet this demand, Palestinian wine makers planned to start new grape growing areas in Samaria. The end of Prohibition in the United States and the permission to import Palestinian wine brought new life to the wine growing business in Palestine. However, in Poland, sales of Palestinian wine were very low in 1936 because Jewish buyers faced poverty.

Modern Wine Industry: Today's Wineries

Cremisan Winery, started in 1885, is the oldest winery in Palestine. It makes award-winning wines that are sold around the world. The vineyard was founded and is owned by the Salesian monks. They started it to create jobs for local people and to help those in need.

Nadim Khoury, a Palestinian known for starting Taybeh Brewery, has also opened a winery in the Christian village of Taybeh in the West Bank. He uses 21 different types of local grapes. The wines he produces quickly became popular with visitors. Khoury says that Israeli rules have made it hard to do business. For example, his shipments, including his wine-making equipment, have been delayed because of inspections at Israeli checkpoints. Another problem for business owners is difficulty shipping to the United States. This is because there is no free trade agreement between the two countries. A wine festival is now held every year in Taybeh.