Portraiture of Elizabeth I facts for kids

The portraits of Queen Elizabeth I (1533–1603) show how royal paintings changed in England. They started as simple pictures of a person. Later, they became complex images that showed the power of the country and its queen.

Even early portraits of Elizabeth I included special objects. These were like roses and prayer books. They had important meanings for people back then. Later portraits added symbols of an empire. These included globes, crowns, swords, and columns. They also showed symbols of virginity and purity, like moons and pearls. These pictures told a complex "story" to people in the Elizabethan era. They showed the greatness and importance of the 'Virgin Queen'.

Contents

Understanding Elizabeth's Portraits

Painting in Tudor England

In the time of Elizabeth's father, Henry VIII, two main ways of painting portraits developed.

- The portrait miniature was a very small, personal painting. These were usually done from life using watercolours on vellum (a type of treated animal skin).

- Larger oil paintings were done on wood panels or canvas. These were usually life-sized.

Elizabeth did not give one artist the only right to paint her. However, Nicholas Hilliard was her official miniaturist. George Gower, a popular court painter, was in charge of approving all portraits of the queen from 1581 until he died in 1596.

Elizabeth sat for many artists, including Hilliard, Cornelis Ketel, Federico Zuccaro, Isaac Oliver, and likely Gower. The government ordered portraits as gifts for other rulers. Courtiers also asked for paintings to show their loyalty to the queen. Artists' studios made many copies of Elizabeth's image. They used approved "face patterns" (drawings of her face) to meet the high demand. Her image was a key symbol of loyalty during a time of change.

How the Royal Image Was Created

William Gaunt compared an early portrait of Elizabeth as a princess to her later images as queen. He noted how simple the 1546 portrait was. It showed her looking quiet and thoughtful. Later portraits were much grander. They showed her with a pale, mask-like face and fancy clothes. This made her seem less human and more like a symbol.

From the 1570s, the government wanted to control how the queen was seen. They wanted her to be seen as someone to admire and respect. This was part of an effort to replace old religious traditions after the English Reformation. The queen's image became a symbol of national pride and order. By the end of her reign, portraits showed her as forever young, even as she grew older.

Early Portraits of the Queen

The Young Queen

Early portraits of Elizabeth show her looking natural and calm. Many of these were probably made to show to possible husbands and foreign leaders.

The full-length Hampden portrait shows Elizabeth in a red satin dress. This was an important early painting. It was made when her image was being carefully controlled. In some early paintings, Elizabeth holds a book, showing she was studious or religious. In others, she wears a red rose, a symbol of the Tudor Dynasty. Or she wears white roses, which stood for the House of York and purity. In the Hampden portrait, she wears a red rose and holds a flower called a gillyflower.

Levina Teerlinc was a Flemish artist who worked for Elizabeth. She was known for her small portrait miniatures. She made many portraits of Elizabeth, but only a few have survived.

Elizabeth and the Goddesses

Two allegorical paintings (paintings with a hidden meaning) show how classical myths were used. They showed the beauty and power of the young queen.

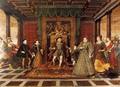

- In Elizabeth I and the Three Goddesses (1569), Elizabeth is shown choosing among three goddesses. But she outshines them all with her crown and royal orb. This painting suggests that Elizabeth's rule brings peace and order to England.

- The 1572 painting The Family of Henry VIII: An Allegory of the Tudor Succession also has a hidden meaning. It shows Catholic Mary and her husband with Mars, the god of War. Protestant Elizabeth, however, brings in the goddesses Peace and Plenty. This painting likely celebrated a treaty between England and France.

These paintings showed Elizabeth's fair rule. They were often made by Flemish artists who had found safety in England from religious persecution.

Hilliard and the Queen

Nicholas Hilliard was trained as a goldsmith and miniaturist. His first known miniature of the Queen is from 1572. He was later officially appointed as her miniaturist. Two larger panel portraits, the Phoenix and Pelican portraits, are from around 1572–76. They are named after the jewels Elizabeth wears. These jewels were her personal symbols: the pelican (meaning devotion) and the phoenix (meaning rebirth).

Hilliard's larger portraits were not always popular. So, in 1576, he went to France to improve his skills. When he returned, he continued to make beautiful "picture boxes" or lockets for miniatures. The Armada Jewel and the Drake Pendant are famous examples. Courtiers were expected to wear the Queen's image, especially at court.

Hilliard also decorated important documents. For example, he worked on the founding charter of Emmanuel College, Cambridge in 1584. This document shows Elizabeth on her throne with fancy decorations.

The Darnley Portrait

The Darnley Portrait became the official image of Elizabeth. It was likely painted from life around 1575–76. This portrait provided a "face pattern" that was used for many other official portraits of Elizabeth. This helped keep her looking young and beautiful in paintings for many years. Some believe the artist was Federico Zuccari, a famous Italian artist. However, experts at the National Portrait Gallery now think it was painted by an unknown European artist.

The Darnley Portrait was the first Tudor painting to show the crown and sceptre placed on a table next to the queen. This idea of using these symbols as props became common in later portraits. Recent cleaning has shown that Elizabeth's pale skin in this portrait is due to the fading of red colors over time.

The Virgin Empress of the Seas

Return of the Golden Age

In 1570, the Pope removed Elizabeth from the church. This led to more tension with Philip II of Spain. Philip supported Mary, Queen of Scots, as the rightful queen of England. This tension grew over the next few decades, leading to the attempted invasion by the Spanish Armada.

Because of this, portraits of Elizabeth began to show her with strong symbols of her power over the seas. These paintings also showed her as the Virgin Queen. This helped create an image of Elizabeth as the chosen Protestant protector of her people.

This new style of painting started around 1579. It was inspired by John Dee. He wrote a book in 1577 that encouraged England to build colonies and a strong navy. He linked Elizabeth to ancient British kings like Brutus of Troy and King Arthur. This idea was based on old stories that Elizabethans believed were true. They thought the Tudors were linked to ancient heroes and would bring a "Golden Age" of peace.

The Virgin Queen

A series of Sieve Portraits used the same face from the Darnley painting. They added a story about Elizabeth being like Tuccia. Tuccia was a Vestal Virgin who proved her purity by carrying water in a sieve without spilling it. The first Sieve Portrait was by George Gower in 1579. The most famous one was by Quentin Metsys the Younger in 1583.

In the Metsys version, Elizabeth is surrounded by symbols of empire, like a column and a globe. These symbols appeared often in her portraits in the 1580s and 1590s. The medallions on a pillar show the story of Dido and Aeneas. This suggests that Elizabeth, like Aeneas, was meant to reject marriage and build an empire.

Another symbol of purity is the spotless ermine. This animal appears in the Ermine Portrait of 1585. In this painting, Elizabeth holds an olive branch, a symbol of peace. A sword of justice rests beside her. Together, these symbols showed Elizabeth's personal purity and the fairness of her rule.

Visions of Empire

The Armada Portrait is a famous painting that tells a story. It shows the queen surrounded by symbols of her empire. In the background, it shows the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588.

There are three main versions of this portrait. Experts believe they were all made by different English artists' workshops.

In the painting, Elizabeth's hand rests on a globe, covering the Americas. This shows England's power over the seas and its dreams of building colonies. Behind her are two columns. These might refer to the Pillars of Hercules, which were seen as the gateway to the Atlantic and the New World.

On the left side of the background, English fireships threaten the Spanish fleet. On the right, the Spanish ships are driven onto a rocky coast by a storm. This storm was called the "Protestant Wind" by the English, who saw it as God's help. These images also show Elizabeth turning her back on storms and darkness, with sunlight shining where she looks.

An engraving from 1596 by Crispijn van de Passe shows similar symbols. Elizabeth stands between two columns with her royal symbols. Ships fill the sea behind her.

The Cult of Elizabeth

After the defeat of the Spanish Armada, the symbols used for Elizabeth became very complex. In poems, portraits, and celebrations, the queen was called Astraea, the fair virgin. She was also called Venus, the goddess of love. Her purity was also linked to the moon goddess, who ruled the waters. Sir Walter Raleigh used names like Diana and Cynthia for the queen in his poems. Portraits began to show Elizabeth with crescent moons or arrows, symbols of the huntress. Courtiers wore her image and her colors (black and white) to show their loyalty.

The Ditchley Portrait was likely painted for Sir Henry Lee of Ditchley. It probably celebrated Elizabeth's visit to his home in 1592. The painting is thought to be by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger. In it, the queen stands on a map of England, with her feet on Oxfordshire. Storms are behind her, and the sun shines in front. She wears a jewel shaped like a celestial sphere. Many copies of this painting were made, often with the allegorical items removed.

The Last Sitting and the Mask of Youth

Around 1592, Elizabeth also sat for Isaac Oliver, a student of Hilliard. Oliver made an unfinished miniature that was used for engravings of the queen. Only one finished miniature from this sitting survives. It shows the queen's features softened. This realistic image of the aging Elizabeth was not considered a success.

Before the 1590s, images of the queen were mostly in books. But in this decade, individual prints of the queen appeared. In 1596, the Privy Council ordered that "unseemly" portraits of the queen be found and burned. These were likely prints that showed the aging queen. From 1596 until her death in 1603, no surviving portraits show Elizabeth as she truly looked. Instead, artists used a "Mask of Youth" face pattern created by Nicholas Hilliard. This made Elizabeth appear forever young.

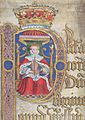

The Coronation Portraits

Two portraits of Elizabeth in her coronation robes exist, both from around 1600. One is a large oil painting, and the other is a miniature by Nicholas Hilliard. Records show that Elizabeth's coronation robes were remade from her sister Mary I's. The paintings accurately show these robes, though the jewels are different. It's not known why these portraits were made so late in her reign.

The Rainbow Portrait

The Rainbow Portrait at Hatfield House is one of the most symbolic paintings of the queen. It was painted around 1600–1602, when Elizabeth was in her sixties. In this painting, an ageless Elizabeth wears a linen top with spring flowers and a cloak. Her hair is loose under a fancy headdress. She carries a rainbow with the Latin motto non sine sole iris, meaning "no rainbow without the sun." She also wears symbols from popular emblem books, like a cloak with eyes and ears, a serpent (for wisdom), and a celestial sphere. This complex painting may have been designed by the poet John Davies. It was likely made for Elizabeth's visit in 1602, which was one of the last big celebrations of her reign.

Books and Coins

Before prints became common, most people in England saw Elizabeth's image on coins. In 1560, new, good quality coins were made. This was a big achievement for Elizabeth. Later coins showed the queen in a symbolic way, with Tudor symbols like the Tudor rose and portcullis.

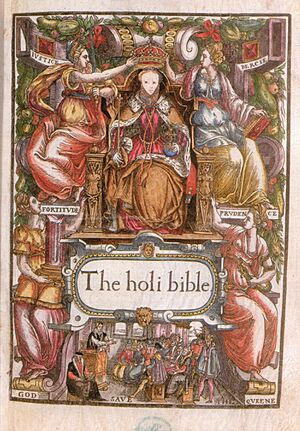

Books also showed images of Elizabeth. Her portrait appeared on the title page of the Bishops' Bible, the main Bible of the Church of England. This Bible was first published in 1568. In different versions, Elizabeth is shown with her orb and sceptre, along with female figures representing ideas.

Reading the Portraits

The many portraits of Elizabeth I are full of meaning. They use ideas from classical mythology, English history, and poems. This makes it hard for us today to understand them exactly as people in Elizabeth's time did. Even though we know some of the symbols, the most complex portraits might have been made for specific events or celebrations. The famous Armada, Ditchley, and Rainbow portraits are all linked to unique events. If we don't know the full story behind other portraits, we might miss their deeper meanings. Elizabethan courtiers knew the "language of flowers" and emblem books. They could "read" stories in the flowers the queen carried, the embroidery on her clothes, and her jewels.

Experts say that Elizabethans were careful about how images were used. They saw images as signs or symbols that led the viewer to understand a bigger idea. Elizabeth's portraits became like "texts" that needed to be "read" by the viewer. As her reign went on, her portraits became more like collections of abstract patterns and symbols. These were arranged in an unnatural way for the viewer to figure out. By doing so, people could understand the idea of monarchy itself.

Images for kids

-

An Elizabethan Maundy, miniature by Teerlinc, around 1560

-

The Procession Portrait, around 1600, attributed to Robert Peake the Elder

-

The Pelican Portrait, around 1575, probably by Nicholas Hilliard

-

The Welbeck or Wanstead Portrait, 1580–85, Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder. Elizabeth holds the olive branch of peace.

-

One of five known portraits attributed to John Bettes the Younger or his studio, around 1585–90

-

Another portrait at Jesus College, Oxford unknown artist, around 1590

-

Sir Christopher Hatton wearing a cameo of the queen, 1589.

-

Sir Francis Drake wearing the Drake Pendant, a cameo of the queen. Gheeraerts the Younger, 1591.

-

Engraving by William Rogers from the drawing by Oliver around 1592.

-

Engraving around 1592–95 by Crispijn de Passe from the drawing by Oliver.

-

Irish groat of 1561. Coins were the main way people saw images of Elizabeth.

See also

- 1550–1600 in fashion

- Artists of the Tudor Court

- Cultural depictions of Elizabeth I of England

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |