Pterosaur facts for kids

Quick facts for kids PterosaursTemporal range: Upper Triassic – Upper Cretaceous

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

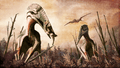

| Coloborhynchus piscator, an Upper Cretaceous pterosaur. |

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: |

Pterosauria

Kaup, 1834

|

| Suborders | |

Pterosaurs were amazing flying reptiles that lived during the Mesozoic era, at the same time as the dinosaurs. They were the first vertebrates (animals with backbones) to develop true powered flight.

Most pterosaurs were quite small, but some grew to be huge, with wingspans larger than any other flying animal. For example, the pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus had a wingspan of up to 12 meters (about 40 feet)!

The oldest pterosaur fossils are from the Upper Triassic period. These creatures lived until the K/T extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous period, which was about 220 to 65.5 million years ago. Their wings were made from a flap of skin stretched between their bodies and a very long fourth finger, often called the "wing finger."

Pterosaurs are divided into two main groups. The older group, called Rhamphorhynchoids (like Rhamphorhynchus), had long tails and jaws full of teeth. The newer group, called Pterodactyloids (like Pterodactylus), had short tails. Many of them had beaks instead of teeth.

The very first pterosaur fossil was found in Germany in 1784. This was in the same place where the famous bird-like dinosaur Archaeopteryx was discovered years later. In 1801, a scientist named Georges Cuvier was the first to suggest that these fossils belonged to flying creatures. Since then, many more pterosaur species have been found in that area. A famous early discovery in the UK was a Dimorphodon fossil found by Mary Anning in 1828. The name Pterosauria was created in 1834.

Pterosaurs were true fliers, meaning they could flap their wings or glide through the air. Their bodies were covered with fine hairs, which helped them control their body temperature, showing they were warm-blooded. They are closely related to dinosaurs and are part of a larger group called Archosauria.

Contents

Types of Pterosaurs

Rhamphorhynchoids: The Early Fliers

This group of early pterosaurs lived successfully from the Upper Triassic to the Lower Cretaceous periods. When we first see their fossils, they already show up as three different families, which means their very early evolution is still a mystery. These families include well-known types like Rhamphorhynchus, Dimorphodon, and Eudimorphodon. Another family, the Anurognathidae, appeared at the beginning of the Jurassic period.

Rhamphorhynchoids had long tails, which were usually kept straight by rod-like bones called tendons. This long, stiff tail helped them fly very steadily, meaning they flew in a straight line rather than darting around. This stable flight style is also seen in early birds like Archaeopteryx, early bats, and insects like dragonflies.

Imagine early planes or large airliners; they are designed to be very stable. To fly quickly and change direction fast, like a fighter plane, requires a more advanced brain and quick reflexes. Early pterosaurs didn't have these, so stable flight was better for them.

All species in this group had teeth. Many early birds, like Archaeopteryx, also had teeth, but modern birds do not. Teeth are quite heavy, and over time, animals that can manage without them tend to lose them through Natural selection. Some birds today use stones in their gizzard or stomach to grind food instead of teeth.

For a long time, people thought this group died out at the end of the Jurassic period, which was a small extinction event. However, new discoveries in China show that some rhamphorhynchoids survived until at least the middle of the Lower Cretaceous.

A single fossil of the insect-eating Anurognathus was also found in Germany. It had a shorter tail than other rhamphorhynchoids. This shorter tail suggests it needed to be agile and quick to catch insects while flying.

Pterodactyloids: The Later, More Agile Fliers

Fossils of pterodactyloids first appear in the Upper Jurassic period. These pterosaurs had short tails, which suggests they had more advanced control over their flight. This likely gave them an advantage in the air. Many different species of pterodactyloids have been found, including early examples of Pterodactylus and Germanodactylus.

Ctenochasma, another pterosaur from this time, had a comb-like mouth with 260 thin teeth. This shows it was a filter-feeder, meaning it probably waded or swam in the water, straining out small creatures. Several other pterosaurs had similar ways of finding food.

In the Lower Cretaceous, there were many pterodactyloids, most of them quite small. Over time, larger versions evolved. By the Upper Cretaceous, most pterosaurs had huge wingspans. They likely soared long distances on warm air currents. Famous examples include Pteranodon, with a wingspan over 7 meters (20 feet), and Quetzalcoatlus, with a wingspan of 12 meters (40 feet). Scientists are still studying what these giant pterosaurs ate.

As birds became common in the Lower Cretaceous, they likely competed with the smaller pterodactyloids for food and space. This competition might explain why the smaller pterosaur species died out. However, it's hard to know for sure because not many fossils are found in ancient forest areas. The huge Upper Cretaceous pterosaurs probably lived a different lifestyle that birds couldn't yet copy.

As the climate changed in the Upper Cretaceous, becoming colder, the number of pterosaurs decreased. Like most large animals on Earth, the giant pterosaurs did not survive the K/T extinction event. However, some families of birds did survive. This marked the end of the long competition between these two types of flying reptiles, which had lasted for 79 million years during the Cretaceous period.

Pterosaur Lifestyle

What Pterosaurs Ate

Pterosaurs had many different shapes of heads and jaws, which tells us that different types ate different foods, much like birds do today. Most pterosaur fossils have been found in marine strata (layers of rock formed in the sea). This suggests they could fly well over water, and that fish were a common meal for many species. Fish-eating pterosaurs often had long jaws with forward-pointing teeth, perfect for catching slippery fish. Evidence of a last fish meal has even been found in Pteranodon fossils.

One pterosaur, Pterodaustro from Argentina, had comb-like strainers in its mouth. This pterosaur likely ate by scooping up water with its lower jaw and then pushing the water out through these strainers. The strainers would catch any plankton or other tiny creatures in the water, which the pterosaur would then eat. Other species had long, flat lower jaws, suggesting they might have skimmed the surface of the water to catch food.

Another important part of their diet was insects. Flying insects were plentiful during the Mesozoic era. Many pterosaur species show clear signs that insects were their main food. These pterosaurs often had wide mouths with short, peg-like teeth.

How Pterosaurs Flew

For a long time, people thought pterosaurs could only glide and soar, and weren't strong enough to flap their wings. But after aeroplanes were invented, our understanding of flight improved. Scientists showed that pterosaurs could indeed fly by flapping their wings. Studies of their brains also showed that by the end of the Jurassic period, pterosaur brains were more like those of modern birds than of Archaeopteryx.

Recent studies have even used working models to understand how they flew. The wing membrane was about 1mm thick, with tough skin and long fibers to make it strong. You can clearly see these fibers in some fossils. This structure helped their wings handle the stress of flying. The larger pterosaurs were mainly soarers, just like large birds today.

How pterosaurs moved on the ground was a bit of a mystery. However, fossil tracks have been found that show they likely walked on four legs, using both their legs and hands for support.

Pterosaurs also had special bones. They were extremely light, even lighter than bird bones. Some were almost as thin as a piece of paper, and many were nearly hollow. Tiny holes in their bones show they had air sacs that extended into their spine and limb bones, similar to birds. They also had supporting struts inside their bones, which made them stronger. Because of these special bones, even the largest pterosaur, Quetzalcoatlus, probably weighed less than 200 pounds.

Pterosaur Reproduction and Life Cycle

Pterosaurs likely laid eggs, and some pterosaur eggs have been found at fossil sites. There is evidence that some species, like Pteranodon, showed sexual dimorphism, meaning males and females looked different. Skeletons with large head crests and small pelvic bones were probably males.

When several specimens are found in the same place, scientists can tell adults from younger pterosaurs. For example, evidence of tooth wear in Eudimorphodon suggests that young pterosaurs ate insects, while adults ate fish. These warm-blooded reptiles grew quickly, and many parts of their life cycle were similar to birds. The high energy needed for flight explains why both pterosaurs and birds developed similar metabolism (how their bodies use energy). In many ways, birds and pterosaurs are great examples of convergent evolution, where different species develop similar features because they live in similar environments or lifestyles.

Related pages

Images for kids

-

Conical tooth, possibly from Coloborhynchus

-

The skull of Thalassodromeus

-

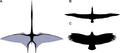

Reconstructed wing planform of Quetzalcoatlus northropi (A) compared to the wandering albatross Diomedea exulans (B) and the Andean condor Vultur gryphus (C). These are not to scale; the wingspan of Q. northropi was more than three times as long as that of the wandering albatross.

-

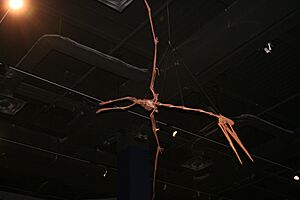

Some specimens, such as this Rhamphorhynchus, preserve the membrane structure

-

Sordes, as depicted here, evidences the possibility that pterosaurs had a cruropatagium – a membrane connecting the legs that, unlike the chiropteran uropatagium, leaves the tail free

-

Engraving of the original Pterodactylus antiquus specimen by Egid Verhelst II, 1784

-

This drawing of Zhejiangopterus by John Conway exemplifies the "new look" of pterosaurs

-

The three-dimensionally preserved skull of Anhanguera santanae, from the Santana Formation, Brazil

-

Life restoration of Lagerpeton, lagerpetids share many anatomical and neuroanatomical similarities with pterosaurs.

-

Skeletal reconstruction of a quadrupedally launching Pteranodon longiceps

-

The probable Azhdarchid trace fossil Haenamichnus uhangriensis.

-

The fossil trackways show that pterosaurs like Hatzegopteryx were quadrupeds, and some rather efficient terrestrial predators.

-

Fossil pterodactyloid juvenile from the Solnhofen Limestone

-

Quetzalcoatlus models in South Bank, created by Mark Witton for the Royal Society's 350th anniversary

-

Scene from When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth depicting an outsized Rhamphorhynchus

See also

In Spanish: Pterosaurios para niños

In Spanish: Pterosaurios para niños