Reginald Fessenden facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Reginald Fessenden

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait photograph of Reginald Fessenden from Harper's Weekly Magazine, 1903

|

|

| Born | October 6, 1866 East Bolton, Quebec, Canada

|

| Died | July 22, 1932 (aged 65) Bermuda (buried St. Mark's Church cemetery)

|

| Nationality | Canadian and American |

| Education | Bishop's College School, University of Bishop's College (dropped out) |

| Occupation | Inventor |

| Known for | Radiotelephony, sonar, Amplitude modulation |

| Spouse(s) | Helen May Trott Fessenden |

Reginald Aubrey Fessenden (October 6, 1866 – July 22, 1932) was a brilliant inventor born in Canada. He spent most of his life working in the United States. He held hundreds of patents for his inventions, especially in radio and sonar.

Fessenden is famous for helping create AM radio. He was the first to send speech by radio in 1900. He also made the first two-way radio call across the Atlantic Ocean in 1906. In 1932, he said he made the first radio broadcast of music and entertainment in late 1906. However, some details about this claim are still debated.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Reginald Fessenden was born on October 6, 1866, in East Bolton, Quebec, Canada. He was the oldest of four children. His father was a minister, so the family moved around Ontario a lot.

Reginald went to several schools as he grew up. At age nine, he attended the DeVeaux Military school for a year. He then went to Trinity College School in Port Hope, Ontario, from 1877 to 1879. He also worked at a bank for a year because he was too young for college.

When he was fourteen, he returned to his hometown. He went to Bishop's College School. There, he got a scholarship and a teaching job in mathematics. So, as a teenager, Fessenden taught math to younger students. At the same time, he studied natural sciences at the college.

At eighteen, Fessenden left Bishop's without a degree. He took a job as headmaster and sole teacher at the Whitney Institute in Bermuda. He worked there for two years. In Bermuda, he met Helen May Trott, and they got engaged. They married in New York City in 1890. Their son, Reginald Kennelly Fessenden, was born in 1893.

Early Career and Electrical Work

Fessenden's early education didn't give him much science or technical training. He wanted to learn more about electricity. So, in 1886, he moved to New York City. He hoped to work for the famous inventor, Thomas Edison.

At first, Edison turned him down. Fessenden wrote, "Do not know anything about electricity, but can learn pretty quick." Edison replied, "Have enough men now who do not know about electricity." But Fessenden kept trying. Soon, he got a job helping to test electrical lines. He quickly showed how good he was. He earned promotions and more important tasks.

In late 1886, Fessenden started working directly for Edison. He was a junior technician at Edison's new lab in West Orange, New Jersey. He worked on many projects, including chemistry, metalwork, and electricity. However, in 1890, Edison had money problems. He had to let go of most lab employees, including Fessenden. Fessenden always admired Edison.

After leaving Edison, Fessenden found jobs with other companies. In 1892, he became a professor at Purdue University. There, he helped the Westinghouse Corporation install lights for the 1893 Chicago World's Fair. Later that year, George Westinghouse hired Fessenden. He became the head of the Electrical Engineering department at the Western University of Pennsylvania in Pittsburgh.

Pioneering Radio Work

In the late 1890s, people started hearing about Guglielmo Marconi's success. Marconi was developing a way to send and receive radio signals. This was called "wireless telegraphy." Fessenden began his own radio experiments. He soon believed he could create a much better system than Marconi's. By 1899, he could send radio messages between Pittsburgh and Allegheny City. He used a receiver he designed himself.

Working with the Weather Bureau

In 1900, Fessenden left Pittsburgh to work for the United States Weather Bureau. His goal was to show that coastal stations could send weather information by radio. This would save money compared to using telegraph lines. He was paid $3,000 a year and given a place to work and live. Fessenden kept ownership of his inventions.

Fessenden quickly made big improvements, especially in how radio signals were received. He invented the barretter detector. Then came the electrolytic detector, which used a fine wire in nitric acid. For several years, this was the best way to receive radio signals.

He also developed the heterodyne principle. This used two close radio signals to make an audible tone. This made Morse code messages much easier to hear. However, this method wasn't practical for another ten years. It needed a stable signal source, which came later with vacuum tubes.

Fessenden's early Weather Bureau work was on Cobb Island, Maryland. This island is in the Potomac River. Later, more stations were built along the Atlantic Coast. But Fessenden had disagreements with his boss, Willis Moore. Fessenden said Moore tried to take half of his patents. Fessenden refused, and his work for the Weather Bureau ended in 1902.

Starting the National Electric Signaling Company

In 1902, two rich businessmen, Hay Walker Jr. and Thomas H. Given, funded a new company. It was called the National Electric Signaling Company (NESCO). This company supported Fessenden's research. They built experimental stations in Washington, D.C., and other cities.

They tried to sell equipment to governments and companies, but didn't have much success. The U.S. Navy, for example, thought Fessenden's prices were too high. This led to bad feelings and lawsuits about patent rights.

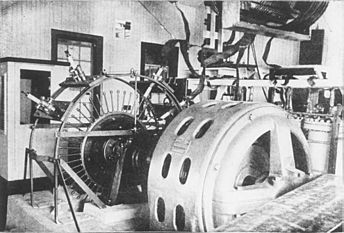

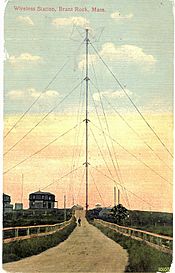

In 1904, NESCO decided to compete with ocean cables. They planned to set up a radio link across the Atlantic Ocean. The company moved its main operations to Brant Rock, Massachusetts. This was to be the western end of the new service.

First Two-Way Transatlantic Radio Call

The plan was to use Fessenden's rotary spark-gap transmitters for the transatlantic service. A tall, 420-foot (128-meter) antenna was built at Brant Rock. A similar tower was built in Machrihanish, Scotland. In January 1906, these stations made the first successful two-way transmission across the Atlantic. They exchanged Morse code messages. (Marconi had only sent one-way messages at this time).

However, the system didn't work well during the day or in summer. Work was stopped until later in the year. Then, on December 6, 1906, the Machrihanish radio tower fell down in a storm. This ended the transatlantic project before it could start commercial service.

Sending Audio by Radio

Fessenden was very interested in sending audio by radio. Early radio only sent Morse code. As early as 1891, he explored sending different electrical currents. He wanted to create a system to send many telegraph messages at once. He later used this knowledge for radio. He developed the idea of continuous-wave radio signals.

Fessenden's main idea was in his U.S. Patent 706,737, filed in 1901. He wanted to use a fast-spinning electrical machine called an "alternator." This machine would create "pure sine waves" and "a continuous train of radiant waves." In simple terms, it would make a steady, continuous radio signal. At the time, most people thought you needed a big spark to make strong signals.

Fessenden's next step was to add a simple carbon microphone to the transmission line. This microphone would change the radio signal to carry sound. This is what we now call amplitude modulated (AM) radio signals.

Fessenden started his audio transmission research on Cobb Island. He didn't have a continuous-wave transmitter yet. So, he used an experimental "high-frequency spark" transmitter. On December 23, 1900, he successfully sent speech about one mile (1.6 kilometers). He said, “One, two, three, four. Is It snowing where you are, Mr. Thiessen? If so, telegraph back and let me know.” This was likely the first successful audio transmission by radio. However, the sound was very distorted.

Some people say the Brazilian inventor Roberto Landell de Moura transmitted his voice earlier. Reports say his transmission reached 8 km on June 3, 1900.

Fessenden kept working on better spark transmitters. He even tried to sell this "radiotelephone." He said that in 1904, it worked well enough for people to sign papers saying the sound was clear over twenty-five miles.

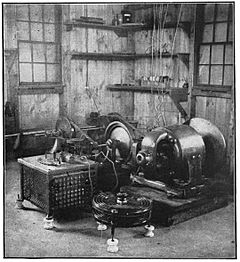

The Alternator-Transmitter

Fessenden's big plan for an audio transmitter was to use a special electrical machine. It was an alternator that spun extremely fast. This would create electrical currents at tens of thousands of cycles per second (kHz). When connected to an antenna, it would make a steady continuous radio wave.

It took many years and a lot of money to build a working prototype. One worry was that the alternator might break apart from spinning so fast. So, it was placed in a pit surrounded by sandbags as a safety measure.

Fessenden worked with General Electric (GE) to design these high-frequency alternators. In 1903, GE delivered a 10 kHz version, but it wasn't very useful for radio. Fessenden asked for a faster, more powerful one. Ernst Alexanderson at GE delivered an improved model in August 1906. It worked at about 50 kHz.

The alternator-transmitter successfully sent good quality audio signals. But there was no way to make the signals louder, so they were somewhat weak. On December 21, 1906, Fessenden showed off the new alternator-transmitter at Brant Rock. He showed it could be used for wireless phone calls. He even connected his stations to the regular phone network. Speech was sent 18 kilometers (11 miles) to Plymouth, Massachusetts.

Although these tests were mainly for short distances, the Brant Rock audio transmissions were sometimes heard across the Atlantic. An employee named James C. Armor heard them at the Machrihanish site in Scotland.

First Entertainment Radio Broadcast?

For a long time, people thought Lee de Forest was the first to broadcast music and entertainment by radio. He started test broadcasts in 1907. His first entertainment broadcast was in February 1907, sending electronic music from his lab.

However, in 1932, an article by Samuel M. Kintner, a former Fessenden colleague, shared new information. It included details from a letter Fessenden sent to Kintner in 1932. Fessenden said that on the evening of December 24, 1906 (Christmas Eve), he made the first radio broadcast of music and entertainment. He used the alternator-transmitter at Brant Rock.

Fessenden remembered playing a phonograph record of music. He also played O Holy Night on the violin and sang. He ended with a Bible passage. He said a second short program was broadcast on December 31 (New Year's Eve). The broadcasts were meant for ship radio operators along the Atlantic coast. Fessenden claimed the Christmas Eve broadcast was heard as far as Norfolk, Virginia. He said the New Year's Eve broadcast reached listeners in the West Indies.

In 2006, for the 100th anniversary, there was new interest in Fessenden's claims. A key question was why there was no other proof for his story. No ship logs or old writings confirmed it. While Fessenden had the technology to broadcast, his station's power was very low. It's questionable if the signal could have reached hundreds of kilometers away.

Some historians believe the December 21 demonstration, which included playing a phonograph record, should count as an entertainment broadcast. Others say there's no reason to doubt Fessenden's account. The debate continues.

Fessenden himself didn't seem to think much about regular broadcasting. In a 1908 review of "Wireless Telephony," he listed possible uses. He only mentioned point-to-point communication, like phone calls between cities or ships. He didn't mention broadcasting to many listeners.

Leaving NESCO

Fessenden's great inventions didn't lead to financial success. The owners of NESCO hoped to sell the company. But they couldn't find a buyer. Fessenden and the company owners started to disagree more and more. In January 1911, Fessenden was fired from NESCO.

He sued NESCO for breaking their contract. Fessenden won the first trial, but NESCO won on appeal. NESCO went into financial trouble in 1912. The legal fight continued for over 15 years. In 1921, NESCO's assets, including Fessenden's important patents, were sold to the Radio Corporation of America (RCA). RCA also took over the lawsuits. Finally, in 1928, Fessenden settled with RCA and received a large sum of money.

Later Years and Other Inventions

After Fessenden left NESCO, Ernst Alexanderson continued developing the alternator-transmitter at General Electric. He created the powerful Alexanderson alternator, which could send signals across the Atlantic. After 1920, radio broadcasting became popular. Even though new stations used vacuum tubes, they used the same continuous-wave AM signals Fessenden had introduced.

Fessenden stopped radio research after 1911, but he kept inventing in other areas. In 1904, he helped design the Niagara Falls power plant. His most important work was in marine communication. He worked for the Submarine Signal Company. This company made a navigation aid using underwater bells.

While there, he invented the Fessenden oscillator. This device could send and receive sound waves underwater. It was used for underwater telegraphy and measuring distances. This was the basis for sonar (SOund NAvigation Ranging). Sonar uses sound to find things underwater, like submarines or icebergs. This helped prevent disasters like the sinking of the Titanic.

During World War I, Fessenden helped the Canadian government. He developed devices to find enemy artillery and submarines. He also invented a type of microfilm to keep records of his inventions. He patented ideas for reflection seismology, which helps find oil. He also patented tracer bullets, paging systems, early television ideas, and a special electric drive for ships.

Fessenden was an amazing inventor, holding over 500 patents. He loved to relax and think of new ideas. He was known for being a bit temperamental. His wife said he was never hard to work with, but he was very difficult when it came to politics.

Awards and Recognition

In 1921, the Institute of Radio Engineers gave Fessenden its IRE Medal of Honor. He was upset because he thought it should have been solid gold, not gold-plated. He returned it, but later accepted it when he learned other medals were also plated.

The next year, he received a John Scott Medal and $800 for his radio inventions. Fessenden was suspicious of these awards. He felt they were given to make him happy, not out of true respect. In 1929, he won Scientific American's Safety at Sea Gold Medal. This was for his invention of the Fathometer and other safety tools for ships.

Death and Legacy

After settling his lawsuit with RCA, Fessenden bought an estate in Hamilton Parish, near Flatts Village in Bermuda. He died there on July 22, 1932. He was buried in the cemetery of St. Mark's Church, Bermuda.

Since 1961, the Society of Exploration Geophysicists has given the Reginald Fessenden Award each year. It honors someone who has made important technical contributions to finding things underground. In 1980, a scholarship was created at Purdue University in his and his wife's memory.

Reginald A. Fessenden House

Fessenden's home at 45 Waban Hill Road in Chestnut Hill, Newton, Massachusetts, is a U.S. National Historic Landmark. He bought the house around 1906 and owned it for the rest of his life.

See also

In Spanish: Reginald Fessenden para niños

In Spanish: Reginald Fessenden para niños

- Reginald Fessenden patents

- Alexanderson alternator: used by Fessenden for his first radio broadcast.

- Sonar

- List of Bishop's College School alumni

Patents

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |