Roman law facts for kids

Roman law is the legal system used in ancient Rome. It includes all the legal ideas and changes that happened over more than a thousand years. This period stretched from the Twelve Tables (around 449 BC) to the Corpus Juris Civilis (AD 529), which was ordered by Emperor Justinian I in the Eastern Roman Empire.

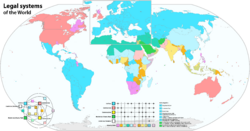

Roman law is the main foundation for civil law, which is the most common legal system used around the world today. Sometimes, people even use the terms "Roman law" and "civil law" to mean the same thing. The lasting importance of Roman law can be seen in the many Latin legal words still used in legal systems today, even in common law.

After the Western Roman Empire ended, Roman law continued to be used in the Eastern Roman Empire. From the 600s onwards, the main language for law in the East became Greek.

Roman law was also the legal system used in most of Western Europe until the late 1700s. In Germany, Roman law was practiced even longer under the Holy Roman Empire (963–1806). So, Roman law became the basis for legal practice across Western Europe and in many former colonies of European nations, like Latin America and Ethiopia. Even English and Anglo-American common law were influenced by Roman law, especially in their Latin legal words. For example, words like stare decisis (meaning "to stand by things decided") come from Roman law. Eastern Europe was also shaped by the Corpus Juris Civilis, especially in countries like medieval Romania, where a new system mixed Roman and local laws.

Contents

How Roman Law Developed

Before the Twelve Tables (754–449 BC), private law in Rome was called ius civile Quiritium. This law only applied to Roman citizens and was closely tied to religion. It was very strict, formal, and traditional. For example, the ritual of mancipatio was a special way to make a sale. A legal expert named Sextus Pomponius said that at the very beginning, Romans had no fixed laws and everything was decided by their kings.

The Twelve Tables

The very first written laws in Rome were the Twelve Tables, created in the mid-400s BC. A leader of the common people, C. Terentilius Arsa, suggested that laws should be written down. This would stop judges from making unfair decisions. After eight years of disagreements, the common people convinced the rich families (patricians) to send a group to Athens to study their laws. They also visited other Greek cities.

In 451 BC, according to old stories, ten Roman citizens were chosen to write down the laws. They were called the decemviri. While they worked, they were given supreme power, and the power of other officials was limited. In 450 BC, the decemviri created ten tablets of laws. But the common people thought these laws were not good enough. So, another group is said to have added two more tablets in 449 BC. The new Law of the Twelve Tables was then approved by the people's assembly.

Today, many scholars question how accurate these old stories are. They don't think a second group of decemviri ever existed. They believe the first group in 451 BC wrote down the most important customs and took charge in Rome. Also, there's a lot of debate about how much Greek law influenced early Roman law. Many scholars think it's unlikely that Romans sent an official group to Greece. Instead, they suggest Romans learned about Greek laws from Greek cities in Magna Graecia (southern Italy), which was a main link between the Roman and Greek worlds. The original text of the Twelve Tables is lost. The tablets were probably destroyed when Rome was attacked and burned by the Gauls in 387 BC.

The parts of the Twelve Tables that survived show that it wasn't a complete law book like we have today. It didn't cover every possible situation or give solutions for all cases. Instead, the tablets contained specific rules meant to change the existing customary law. While the rules covered all areas of law, most of them were about private law (laws between individuals) and civil procedure (how court cases work).

Early Laws and Legal Experts

Some very important laws passed during the early Roman Republic included:

- The Lex Canuleia (445 BC): This law allowed marriage between rich families (patricians) and common people (plebeians).

- The Leges Liciinae Sextiae (367 BC): This law limited how much public land any citizen could use. It also said that one of the two yearly consuls (top officials) had to be a plebeian.

- The Lex Ogulnia (300 BC): This allowed plebeians to hold certain religious offices.

- The Lex Hortensia (287 BC): This law made decisions made by plebeian assemblies binding on everyone in Rome, both patricians and plebeians.

Another important law from the Republic was the Lex Aquilia of 286 BC. This law is seen as the beginning of modern tort law (laws about harm caused to others). However, Rome's biggest gift to European legal culture wasn't just good laws. It was the rise of professional jurists (legal experts) and the development of law as a science. This happened gradually by using the scientific methods of Greek philosophy to study law, something the Greeks themselves never did.

Traditionally, the start of Roman legal science is linked to Gnaeus Flavius. Around 300 BC, Flavius is said to have published the secret legal forms used in court. Before him, only priests knew these forms. Publishing them allowed non-priests to understand legal texts. Whether this story is true or not, legal experts were active and writing legal books before the 2nd century BC. Famous jurists from the Republic include Quintus Mucius Scaevola Pontifex, who wrote a huge book on all parts of law, and Servius Sulpicius Rufus, a friend of Marcus Tullius Cicero. By the time the Roman Republic became an empire in 27 BC, Rome had a very advanced legal system and a sophisticated legal culture.

Pre-Classical Period

Between about 201 BC and 27 BC, Roman laws became more flexible to meet new needs. Besides the old and formal ius civile, a new type of law was created: the ius honorarium. This was law introduced by magistrates (officials) who could issue edicts (public announcements) to support, add to, or correct existing law. With this new law, the old strict rules were left behind, and new, more flexible principles of ius gentium (law of nations) were used.

The job of adapting law to new needs fell to legal practice, especially to the praetors. A praetor was not a lawmaker. He didn't technically create new law when he issued his edicts. However, his rulings often led to new legal rules. A praetor's successor was not bound by the edicts of the previous praetor. But they often kept rules from older edicts that had proven useful. This way, a consistent set of rules developed from one edict to the next.

Over time, a new body of praetoric law grew alongside and improved the civil law. The famous Roman jurist Papinian (142–212 AD) defined praetoric law as: "Praetoric law is that law introduced by praetors to help, add to, or correct civil law for the public good." Eventually, civil law and praetoric law were combined in the Corpus Juris Civilis.

Classical Roman Law

The first 250 years of the current era are known as the "classical period of Roman law." During this time, Roman law and legal science became very advanced. The work of the jurists (legal experts) from this period gave Roman law its unique shape.

These jurists did many things:

- They gave legal advice to private citizens.

- They advised magistrates who handled justice, especially the praetors.

- They helped praetors write their edicts, which announced how they would handle their duties.

- Some jurists also held high judicial and administrative jobs themselves.

Jurists also wrote many legal texts. Around AD 130, the jurist Salvius Iulianus created a standard form for the praetor's edict. All praetors used this edict from then on. This edict described in detail all the cases where a praetor would allow a legal action or grant a defense. The standard edict acted like a complete law code, even if it wasn't formally a law. It showed what was needed for a successful legal claim. This edict became the basis for many legal comments by later classical jurists like Paulus and Ulpian.

The new ideas and legal systems developed by these jurists are too many to list. Here are a few examples:

- Roman jurists clearly separated the legal right to own something (ownership) from the actual ability to use it (possession).

- They also created the difference between a contract (an agreement) and a tort (a civil wrong) as sources of legal duties.

- The standard types of contracts (like sale, work, hire, services) that are in most modern law codes were developed by Roman legal experts.

- The classical jurist Gaius (around 160 AD) created a system of private law. It divided everything into personae (persons), res (things), and actiones (legal actions). This system was used for centuries. You can still see it in legal books like William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England and in codes like the French Code civil or the German BGB.

The Roman Republic had three different parts of government:

- Assemblies: These groups passed laws and declared wars.

- Senate: This body controlled the government's money.

- Consuls: These were the highest officials with great legal power.

Post-Classical Law

By the mid-200s AD, it became harder for a refined legal culture to thrive. The political and economic situation worsened, and emperors took more direct control over everything. The political system, which had kept some parts of the Republic's constitution, started to become an absolute monarchy. Legal science and jurists who saw law as a science, not just a tool for the emperor's goals, didn't fit well into this new system. Legal writing almost stopped. Few jurists after the mid-200s are known by name. While legal science and education continued somewhat in the eastern part of the Empire, most of the fine details of classical law were ignored and forgotten in the west. Classical law was replaced by what is called "vulgar law," which was simpler.

Types of Roman Law

Concepts of Laws

- ius civile, ius gentium, and ius naturale:

* The ius civile ("citizen law") was the set of common laws that applied only to Roman citizens. The Praetores Urbani were officials who handled cases involving citizens. * The ius gentium ("law of peoples") was the set of common laws that applied to foreigners and their dealings with Roman citizens. The Praetores Peregrini handled cases involving citizens and foreigners. * Jus naturale was an idea developed by jurists to explain why all people seemed to follow some laws. Their answer was that a "natural law" gave all beings a common sense of right and wrong.

- ius scriptum and ius non-scriptum (written and unwritten law):

* In practice, these differed by how they were created, not just if they were written down. * The ius scriptum was the set of laws made by the legislature (lawmaking body). These laws were called leges (laws) and plebiscita (decisions of the common people's council). Roman lawyers also included in ius scriptum the edicts of magistrates, the advice of the Senate, the opinions of jurists, and the emperor's announcements. * Ius non-scriptum was the set of common laws that grew from long-standing customs and became binding over time.

- ius commune and ius singulare (common law and special law):

* Ius singulare (special law) is a unique law for certain groups, things, or legal situations. It's an exception to the general rules of the legal system. * An example is the law about wills written by soldiers during a military campaign. These wills didn't need the same strict formalities that regular citizens had to follow when writing wills in normal times.

- ius publicum and ius privatum (public law and private law):

* Ius publicum meant public law, which protected the interests of the Roman state. * Ius privatum meant private law, which protected individuals. In Roman law, private law included personal law, property law, and civil law. Court cases were private processes, and most crimes were considered private (except for very serious ones handled by the state). Public law only started to include some areas of private law near the end of the Roman state. * Ius publicum also referred to legal rules that could not be changed or ignored by agreement between parties. Today, these are called ius cogens (compelling law).

Public Law

The Roman Republic's constitution, or mos maiorum ("custom of the ancestors"), was a set of guidelines and principles. It wasn't written down formally but was passed down through tradition and past examples. Ideas that started in the Roman constitution are still used in constitutions today. These include:

- Checks and balances: Different parts of government limit each other's power.

- Separation of powers: Government power is divided into different branches.

- Vetoes: The power to reject a law.

- Filibusters: A way to delay a vote on a bill.

- Quorum requirements: A minimum number of members needed to conduct business.

- Term limits: How long someone can stay in office.

- Impeachments: The process of removing an official from office.

- The powers of the purse: Control over government spending.

- Regularly scheduled elections.

Even some less common modern ideas, like the block voting used in the electoral college of the United States, come from the Roman constitution.

The Roman Republic's constitution was not formal or official. It was mostly unwritten and changed constantly throughout the Republic's history. During the 1st century BC, the power and legitimacy of the Roman constitution slowly weakened. Even Roman constitutionalists, like the senator Cicero, became less faithful to it towards the end of the Republic. When the Roman Republic finally fell, what was left of the Roman constitution ended with it. The first Roman emperor, Augustus, tried to make it seem like a constitution still guided the Empire. He used its institutions to make his rule seem legitimate. The belief in a surviving constitution lasted well into the Roman Empire.

Private Law

Stipulatio was the basic type of contract in Roman law. It was made by asking a question and giving an answer. The exact nature of this contract was debated.

Rei vindicatio was a legal action where the plaintiff (the person bringing the case) demanded that the defendant (the person being sued) return something that belonged to the plaintiff. This action could only be used if the plaintiff owned the item and the defendant was somehow stopping the plaintiff from having it. The plaintiff could also use an actio furti (a personal action) to punish the defendant. If the item couldn't be recovered, the plaintiff could claim money for damages using the condictio furtiva (another personal action). With the help of the actio legis Aquiliae (a personal action), the plaintiff could claim damages from the defendant. Rei vindicatio came from the ius civile, so only Roman citizens could use it.

Legal Status

A person's rights and duties in the Roman legal system depended on their legal status (status). A person could be:

- A Roman citizen (status civitatis), unlike foreigners.

- Free (status libertatis), unlike slaves.

- Have a certain position in a Roman family (status familiae). This could be as the head of the family (pater familias) or a younger member alieni iuris (someone living under another's authority).

Court Cases

The history of Roman law can be divided into three systems for court procedures: 1. Legis actiones: Used from the time of the Twelve Tables (around 450 BC) until the late 2nd century BC. 2. Formulary system: Used from the last century of the Republic until the end of the classical period (around AD 200). 3. Cognitio extra ordinem: Used in post-classical times.

These periods overlapped, so one system didn't just stop and another begin suddenly.

During the Republic and before Roman court procedures became more bureaucratic, the judge was usually a private person (iudex privatus). This judge had to be a Roman male citizen. The people involved in the case could agree on a judge, or they could choose one from a list. They would go down the list until they found a judge both parties liked. If they couldn't agree, they had to take the last one on the list.

No one was legally forced to judge a case. The judge had a lot of freedom in how he handled the trial. He considered all the evidence and made a decision that seemed fair. Because the judge was not always a legal expert, he often asked a jurist for advice on technical parts of the case, but he didn't have to follow that advice. If things weren't clear to him at the end of the trial, he could refuse to give a judgment by swearing that he couldn't decide. Also, there was a maximum time limit for issuing a judgment, which depended on the type of case.

Later, as the system became more bureaucratic, this procedure disappeared. It was replaced by the "extra ordinem" procedure, also called cognitory. The entire case was handled by a magistrate in one step. The magistrate was required to judge and make a decision, and that decision could be appealed to a higher magistrate.

Legacy of Roman Law

The German legal expert Rudolf von Jhering famously said that ancient Rome conquered the world three times: first with its armies, second with its religion, and third with its laws. He might have added: each time more completely.

In the East

When the center of the Empire moved to the Greek East in the 300s, many Greek legal ideas appeared in official Roman laws. This influence can be seen even in laws about people or families, which usually change the least. For example, Constantine started to limit the old Roman idea of patria potestas (the power of the male head of a family over his children). He recognized that children under this power could own property. He seemed to be making changes to fit the stricter idea of fatherly authority in Greek-Hellenistic law. The Codex Theodosianus (AD 438) was a collection of Constantine's laws. Later emperors went even further, until Justinian finally ruled that a child under potestas owned everything they acquired, unless they got it from their father.

Justinian's law codes, especially the Corpus Juris Civilis (529–534), continued to be the basis of legal practice in the Empire throughout its Byzantine history. Leo III the Isaurian issued a new code, the Ecloga, in the early 700s. In the 800s, emperors Basil I and Leo VI the Wise ordered a combined translation of parts of Justinian's codes into Greek. This became known as the Basilica. Roman law, as kept in Justinian's codes and the Basilica, remained the basis of legal practice in Greece and in the courts of the Eastern Orthodox Church even after the Byzantine Empire fell and was conquered by the Turks. It also formed the basis for much of the Fetha Negest, which was used in Ethiopia until 1931.

In the West

In the west, Justinian's political power only reached parts of Italy and Spain. However, in the law codes issued by Germanic kings, the influence of early Eastern Roman codes can be clearly seen in some of them. In many early Germanic states, Roman citizens continued to be governed by Roman laws for a long time, while members of the various Germanic tribes followed their own codes.

The Codex Justinianus and the Institutes of Justinian were known in Western Europe. Along with the earlier code of Theodosius II, they served as models for some Germanic law codes. However, the Digest part was mostly ignored for several centuries until around 1070. That's when a copy of the Digest was found again in Italy. This led to the work of "glossators" who wrote comments between the lines or in the margins of the text. From that time, scholars began to study the ancient Roman legal texts and teach others what they learned. The main center for these studies was Bologna. The law school there slowly grew into Europe's first university.

Students who learned Roman law in Bologna (and later in many other places) found that many Roman law rules were better suited for handling complex business deals than the traditional rules used across Europe. Because of this, Roman law, or at least some parts of it, began to be used again in legal practice, centuries after the Roman Empire ended. Many kings and princes actively supported this process. They hired university-trained legal experts as advisors and court officials. They also wanted to benefit from rules like the famous Princeps legibus solutus est ("The sovereign is not bound by the laws"), a phrase first used by the Roman jurist Ulpian.

There were several reasons why Roman law was favored in the Middle Ages. Roman law protected property rights, treated legal subjects equally, and allowed people to pass on their property through wills.

By the mid-1500s, the rediscovered Roman law dominated legal practice in many European countries. A legal system developed that mixed Roman law with parts of canon law (church law) and Germanic customs, especially feudal law. This legal system, common across continental Europe (and Scotland), was known as Ius Commune. This Ius Commune and the legal systems based on it are usually called civil law in English-speaking countries.

Only England and the Nordic countries did not fully adopt Roman law. One reason is that the English legal system was already more developed than its European counterparts when Roman law was rediscovered. So, the practical benefits of Roman law were less clear to English lawyers than to continental ones. As a result, the English system of common law grew alongside Roman-based civil law. English lawyers were trained at the Inns of Court in London, rather than getting degrees in Canon or Civil Law at the Universities of Oxford or Cambridge. However, parts of Roman-canon law were present in England in the ecclesiastical courts (church courts) and, less directly, through the development of the equity system. Also, some ideas from Roman law found their way into common law. Especially in the early 1800s, English lawyers and judges were willing to borrow rules and ideas from continental jurists and directly from Roman law.

The practical use of Roman law and the era of the European Ius Commune ended when national law codes were created. In 1804, the French civil code came into force. During the 1800s, many European states either adopted the French model or wrote their own codes. In Germany, the political situation made it impossible to create a single national law code. From the 1600s, Roman law in Germany had been heavily influenced by local (customary) law and was called usus modernus Pandectarum. In some parts of Germany, Roman law continued to be used until the German civil code (Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, BGB) became law in 1900.

Colonial expansion helped spread the civil law system around the world.

Today

Today, Roman law is no longer directly used in legal practice. However, the legal systems of some countries, like South Africa and San Marino, are still based on the old jus commune. Even where legal practice uses a modern code, many rules come from Roman law. No code completely broke away from the Roman tradition. Instead, Roman law rules were put into a more organized system and written in national languages. Because of this, knowing Roman law is essential to understand today's legal systems. So, Roman law is often still a required subject for law students in civil law jurisdictions. To help students learn and connect internationally, the annual International Roman Law Moot Court was created.

As steps are being taken to unify private law in the member states of the European Union, the old jus commune is seen by many as a good model. It was the common basis of legal practice across Europe, but it also allowed for many local differences.

See also

In Spanish: Derecho romano para niños

In Spanish: Derecho romano para niños