Rosetta Stone facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Rosetta Stone |

|

|---|---|

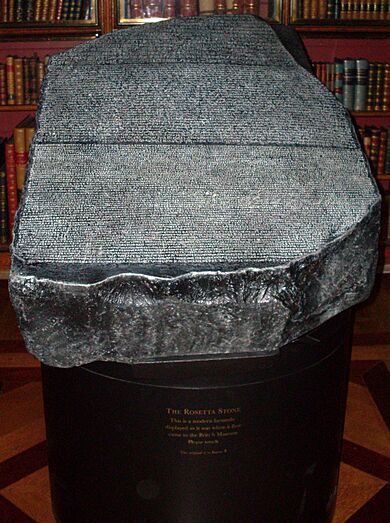

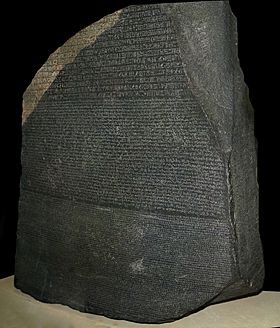

The Rosetta Stone on display

in the British Museum, London |

|

| Material | Granodiorite |

| Size | 1,123 mm × 757 mm × 284 mm (44.2 in × 29.8 in × 11.2 in) |

| Writing | Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, Demotic script, and Greek script |

| Created | 196 BC |

| Discovered | 1799 near Rosetta, Nile Delta, Egypt |

| Discovered by | Pierre-François Bouchard |

| Present location | British Museum |

The Rosetta Stone is a famous stone slab made of a type of rock called granodiorite. It has three different versions of the same message carved into it. This message is a decree (like an official announcement or law) from 196 BC, made during the time of the Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt, on behalf of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes.

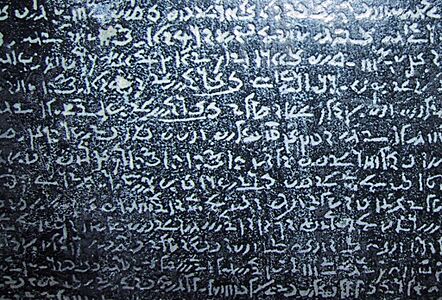

The top part of the stone is written in Ancient Egyptian using hieroglyphs (picture-like symbols). The middle part is also in Ancient Egyptian, but uses a different, simpler script called Demotic. The bottom part is written in Ancient Greek. Because the stone has the same message in three different scripts, it became super important for understanding and translating the ancient Egyptian writing systems that people hadn't been able to read for centuries!

The stone was carved a long, long time ago, during the Hellenistic period (when Greek culture was very influential). It was probably displayed in a temple, maybe in a city called Sais. Over time, it was moved and eventually used as building material for a fort called Fort Julien near the town of Rashid (which is also known as Rosetta) in the Nile Delta.

Contents

How the Rosetta Stone Was Found

In July 1799, a French officer named Pierre-François Bouchard found the stone while his soldiers were building up the defenses of Fort Julien. This happened during Napoleon Bonaparte's military campaign in Egypt. It was the first time in modern history that an ancient Egyptian text with the same message in two languages (Egyptian and Greek) had been found. People were super excited because it meant they might finally be able to understand the mysterious hieroglyphs!

Soon, copies of the stone's text were made and sent to museums and scholars all over Europe. When the British defeated the French in Egypt, they took the Rosetta Stone to London in 1801. Since 1802, it has been on display at the British Museum almost all the time, and it's the most visited object there!

Unlocking Ancient Secrets

Scholars immediately started studying the stone. The Greek text was translated first in 1803. But it was Jean-François Champollion, a French scholar, who finally announced in 1822 that he had figured out how to read the Egyptian scripts. It took even longer for scholars to confidently read all ancient Egyptian inscriptions and literature.

Key breakthroughs in decoding the stone included:

- Realizing that the stone had three versions of the same text (1799).

- Discovering that the Demotic text used phonetic (sound-based) characters for foreign names (1802).

- Figuring out that the hieroglyphic text also used phonetic characters, and that it was similar to the Demotic script (1814).

- Learning that phonetic characters were used for native Egyptian words too (1822–1824).

Even though a few other copies of the same decree and similar bilingual Egyptian inscriptions have been found since, the Rosetta Stone was the crucial key. It opened up our modern understanding of ancient Egyptian writing and civilization. That's why the phrase "Rosetta Stone" is now used to mean an essential clue that helps unlock a new area of knowledge!

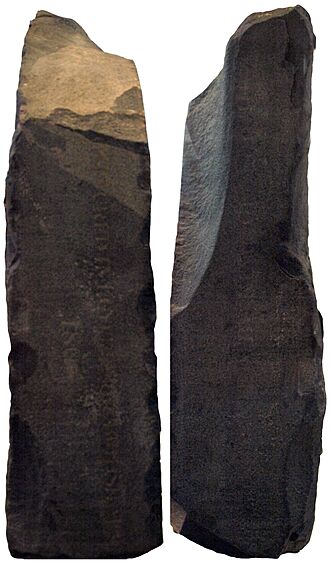

What Does the Rosetta Stone Look Like?

The Rosetta Stone is described as a "stone of black granodiorite". When it first arrived in London, people colored the inscriptions with white chalk to make them easier to read, and covered the rest with wax to protect it. This made the stone look dark, leading people to mistakenly think it was black basalt.

However, when the stone was cleaned in 1999, its true dark grey color, sparkling crystals, and a pink vein in the top left corner were revealed. Experts compared it to rock samples and found it closely matched granodiorite from a quarry at Gebel Tingar near Aswan in Egypt. The pink vein is typical of rock from that area.

The Rosetta Stone is about 112.3 cm (3 ft 8 in) (about 3.7 feet) tall, 75.7 cm (2 ft 5.8 in) (about 2.5 feet) wide, and 28.4 cm (11 in) (about 11 inches) thick. It weighs around 760 kilograms (1,680 lb) (about 1,675 pounds)!

It has three inscriptions:

- The top part: Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs.

- The middle part: Egyptian Demotic script.

- The bottom part: Ancient Greek.

It's important to remember these are not three different languages, but three different scripts (ways of writing) for the same message. The front of the stone is polished, and the carvings are lightly cut into it. The sides are smooth, but the back is rough, probably because it wasn't meant to be seen when the stone was standing upright.

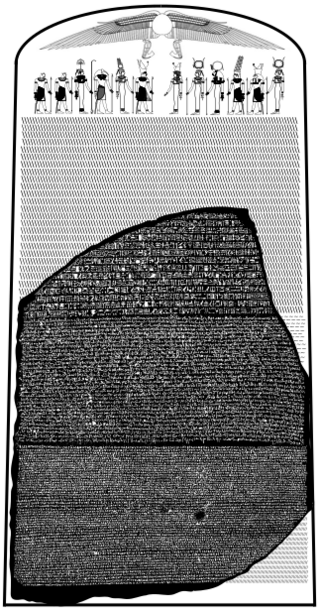

The Original Stone Slab

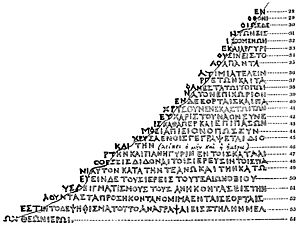

The Rosetta Stone is actually just a piece of a much larger stone slab, called a stele. No other pieces of the original stone have been found at the Rosetta site. Because it's broken, none of the three texts on it are complete.

- The hieroglyphic text at the top is the most damaged. Only the last 14 lines are visible, and they are broken on both the right and left sides.

- The Demotic text in the middle is the best preserved, with 32 lines.

- The Greek text at the bottom has 54 lines, but the bottom right corner is broken, so the last lines are incomplete.

By comparing the Rosetta Stone to other similar stone slabs from that time, experts believe that about 14 or 15 more lines of hieroglyphic text are missing from the top. The original stele was probably much taller, perhaps around 149 centimetres (4 ft 11 in) (about 4.9 feet) high. It likely also had a picture at the top showing the king with the gods, and a winged disc, just like other steles from that period.

The Memphis Decree: Why Was It Made?

The Rosetta Stone was set up after King Ptolemy V was crowned. The message carved on it was a decree issued by a group of priests who met in Memphis, an ancient capital of Egypt. The decree officially established the worship of the new ruler as a god.

The date on the stone corresponds to 27 March 196 BC. This was during a difficult time for Egypt. Ptolemy V became king when he was only five years old, after his parents died suddenly. There were revolts and political struggles happening in Egypt. Other powerful kingdoms, like the Seleucids, were also taking over parts of Egypt's territory.

The decree was made when Ptolemy V was 12 years old, seven years after he became king. It was meant to help the Ptolemaic kings regain control and support from the people of Egypt.

Why Priests Were Important

Steles like the Rosetta Stone, which were set up by temples rather than the king himself, were unique to Ptolemaic Egypt. In earlier Egyptian times, only the pharaohs made big national decisions. But now, the priests were honoring the king in a way that was more common in Greek cities.

The decree mentions that Ptolemy V gave gifts of silver and grain to the temples. It also says that there was a very high flooding of the Nile in his eighth year, and he built dams to help the farmers. In return, the priests promised to celebrate the king's birthday and coronation every year and to serve him alongside the other gods. The decree ends by saying that a copy should be placed in every temple, written in the "language of the gods" (hieroglyphs), the "language of documents" (Demotic), and the "language of the Greeks" (used by the government).

Gaining the support of the priests was super important for the Ptolemaic kings to rule Egypt effectively. The High Priests of Memphis, where the king was crowned, were especially powerful. The fact that the decree was issued in Memphis, the ancient Egyptian capital, rather than Alexandria (the Greek capital), shows that the young king really wanted the priests' active support. Even though the government spoke Greek, the Memphis decree included Egyptian texts to connect with the general population through the educated Egyptian priests.

Where Was It Originally?

The Rosetta Stone was almost certainly not originally placed in Rashid (Rosetta) where it was found. It probably came from a temple further inland, possibly in the royal city of Sais. The temple it came from was likely closed around AD 392 when the Roman emperor Theodosius I ordered all non-Christian temples to be shut down.

The original stele broke at some point, and the largest piece became what we now call the Rosetta Stone. Ancient Egyptian temples were often used as quarries for new buildings, so the Rosetta Stone was probably reused this way. Later, it was built into the foundations of a fortress constructed by the Mameluke Sultan Qaitbay (c. 1416/18–1496) to protect the Bolbitine branch of the Nile at Rashid. It stayed there for at least three centuries until it was found again.

From French to British Hands

After Napoleon's French forces were defeated in Egypt, a big argument broke out over who owned the archaeological and scientific discoveries they had made, including the Rosetta Stone. The French commander, General Jacques-François Menou, refused to hand them over, saying they belonged to the French scientific institute. But the British General John Hely-Hutchinson wouldn't end the siege until Menou gave in.

Eventually, an agreement was reached, and the transfer of the objects, including the Rosetta Stone, was part of the Capitulation of Alexandria signed by the British, French, and Ottoman forces.

It's not entirely clear how the stone was moved to British hands, as different people told different stories. Colonel Tomkyns Hilgrove Turner, who was supposed to take it to England, later claimed he personally took it from Menou. Another account says a French officer secretly showed the stone to British scholars, hidden under carpets among Menou's belongings.

Turner brought the stone to England on a captured French ship, arriving in Portsmouth in February 1802. His orders were to give it to King George III. The King decided it should be placed in the British Museum. Before going to the museum, it was shown to scholars at the Society of Antiquaries of London in March 1802.

In 1802, the Society made four plaster copies of the inscriptions and sent them to universities in Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh, and Dublin. Soon after, prints of the inscriptions were made and sent to scholars across Europe. By the end of 1802, the stone was moved to the British Museum, where it is today. New inscriptions were painted in white on the stone's edges, stating it was "Captured in Egypt by the British Army in 1801" and "Presented by King George III".

The Rosetta Stone has been on display almost continuously at the British Museum since June 1802. It's the museum's most visited object, and for decades, a simple picture of it was their best-selling postcard!

The stone was originally displayed at a slight angle in a metal stand. For a long time, it didn't have a protective cover, but by 1847, it was put in a frame to protect it from visitors' hands. Since 2004, the stone has been in a special display case in the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery. There's also a replica of the Rosetta Stone in the King's Library of the British Museum that you can touch, showing how it looked to early visitors.

During World War I in 1917, the British Museum was worried about heavy bombing in London, so the Rosetta Stone was moved to safety. It spent two years 15 m (50 ft) underground in a station of the Postal Tube Railway. Other than during wartime, the Rosetta Stone has only left the British Museum once: for one month in October 1972, when it was displayed at the Louvre in Paris. Even when it was being cleaned in 1999, the work was done in the gallery so the public could still see it.

Reading the Rosetta Stone: The Decipherment Story

Before the Rosetta Stone was discovered, nobody had understood the ancient Egyptian language and its scripts for over 1,400 years! By the 4th century AD, very few Egyptians could read hieroglyphs. The last known hieroglyphic inscription was made in 394 AD, and the last Demotic text in 452 AD.

Hieroglyphs looked like pictures, and early scholars often misunderstood them, thinking each symbol represented a whole idea rather than a sound. This made it very hard to decode them. Some Arab historians in medieval Egypt tried to study hieroglyphs by comparing them to the Coptic language (a later form of Egyptian) used by Coptic priests. But it wasn't until the Rosetta Stone was found in 1799 that the crucial missing information became available.

The Greek Text: The Starting Point

The Greek text on the Rosetta Stone was the starting point for decipherment. Scholars knew Ancient Greek, but they weren't very familiar with how it was used in Egypt during the Ptolemaic period.

In 1802, Stephen Weston gave an English translation of the Greek text. Meanwhile, two copies of the stone's text reached Paris. Gabriel de La Porte du Theil and Hubert-Pascal Ameilhon worked on the Greek translation, and Ameilhon published the first full translations in 1803. At the same time, Richard Porson in Cambridge worked on reconstructing the missing parts of the Greek text, and Christian Gottlob Heyne in Göttingen made a more reliable Latin translation.

The Demotic Text: A Step Closer

When the stone was found, a Swedish scholar named Johan David Åkerblad was already studying a little-known Egyptian script, which later became known as Demotic. He thought it was a cursive (flowing) form of Coptic.

In 1801, French scholar Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy received a copy of the Rosetta Stone and realized the middle text was in this Demotic script. He and Åkerblad started working on it, assuming the script was alphabetical. They tried to find where Greek names like "Ptolemy" or "Alexandria" would appear in the Demotic text by comparing it to the Greek.

In 1802, Silvestre de Sacy successfully identified five names, and Åkerblad published an alphabet of 29 letters he had found in the Demotic text (more than half were correct!). However, they couldn't identify all the characters because, as we now know, Demotic also included symbols that represented ideas, not just sounds.

The Hieroglyphic Text: The Final Breakthrough

Silvestre de Sacy eventually stopped working on the stone, but he gave a key suggestion to Thomas Young, a British scholar. In 1814, Silvestre de Sacy suggested that Young should look for cartouches (oval shapes enclosing names) in the hieroglyphic text, as these might contain Greek names written phonetically.

Young followed this advice and made two big discoveries:

- He found the phonetic characters for "Ptolemy" in the hieroglyphic text.

- He noticed that these hieroglyphic characters looked similar to the Demotic ones, and found about 80 similarities between the two scripts. This was important because people used to think they were completely different. Young correctly figured out that Demotic was partly phonetic and partly used symbols derived from hieroglyphs.

Young published his findings in the Encyclopædia Britannica in 1819, but he couldn't make further progress.

In 1814, Young started writing to Jean-François Champollion, a French teacher who was also studying ancient Egypt. In 1822, Champollion saw copies of inscriptions from the Philae obelisk where the names "Ptolemy" and "Kleopatra" were written in both Greek and hieroglyphs. From this, Champollion identified the phonetic characters for "Kleopatra".

Using this and the foreign names on the Rosetta Stone, Champollion quickly built an alphabet of phonetic hieroglyphic characters. He announced his discovery on 27 September 1822, in a famous letter called the "Lettre à M. Dacier". In this letter, he noted that similar phonetic characters seemed to be used for both Greek and Egyptian names. This was confirmed in 1823 when he identified the names of ancient pharaohs like Ramesses and Thutmose in much older hieroglyphic inscriptions.

From this point, the story of the Rosetta Stone and the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs branched out, as Champollion used many other texts to create a full grammar and dictionary of Ancient Egyptian, which were published after his death in 1832.

Ongoing Study and Debates

After Champollion's death, scholars continued to work on understanding the texts more fully by comparing the three versions. There were also debates about whether one of the three texts was the original from which the others were translated. Some thought the Greek version was the original, while others believed all three were created at the same time. Today, experts like Richard Parkinson note that the hieroglyphic version sometimes uses language closer to the Demotic script, which priests used more often in daily life. The fact that the three versions aren't exactly word-for-word matches is why the decipherment was harder than expected.

There were also rivalries and arguments between scholars, especially between the British and French, about who deserved credit for the decipherment. Both Thomas Young and Jean-François Champollion made huge contributions, and their early deaths didn't stop the debates about who did what first.

Calls for the Stone to Return to Egypt

Since 2003, Zahi Hawass, who was then the head of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities, has repeatedly asked for the Rosetta Stone to be returned to Egypt. He says it's an "icon of our Egyptian identity." He has also asked for other important Egyptian artifacts in museums around the world to be returned.

In 2005, the British Museum gave Egypt a full-sized, color-matched replica of the stone. This replica is now displayed in the Rashid National Museum in the town of Rashid (Rosetta), near where the original stone was found.

In 2009, Hawass suggested that he would drop his demand for the permanent return of the Rosetta Stone if the British Museum would lend it to Egypt for three months for the opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza.

Many national museums, including the British Museum, generally oppose returning objects of international cultural importance. They argue that objects acquired in earlier times should be seen in the context of that era, and that museums serve people from all nations, not just one.

"Rosetta Stone" as an Idiom

The term "Rosetta Stone" is now often used to describe a crucial clue that helps unlock a new field of knowledge or understand something complex.

For example:

- The Behistun Inscription in Iran is sometimes called a "Rosetta Stone" because it helped translate three ancient Middle Eastern languages: Old Persian, Elamite, and Akkadian.

- In science, the spectrum of hydrogen atoms has been called the "Rosetta Stone of modern physics" because understanding it led to many other discoveries.

- The flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana has been called the "Rosetta Stone of flowering time" because studying its genes helps understand how plants flower.

- The European Space Agency's Rosetta spacecraft was named after the stone because it was sent to study a comet in hopes of understanding the origins of our Solar System.

The name is also used for various translation software and services, like the language-learning software "Rosetta Stone". There's also "Rosetta@home," a project where people use their computers to help predict protein structures, which is like "translating" genetic sequences into shapes.

See also

In Spanish: Piedra de Rosetta para niños

In Spanish: Piedra de Rosetta para niños

- Egypt–United Kingdom relations

- List of individual rocks

- Multilingual inscription

- Transliteration of Ancient Egyptian

- Rosetta (spacecraft)