Sabine's gull facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sabine's gull |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Adult in Iceland | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Laridae |

| Genus: | Xema Leach, 1819 |

| Species: |

X. sabini

|

| Binomial name | |

| Xema sabini |

|

|

|

| Range Breeding Migration Non-breeding | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Sabine's gull (pronounced SAY-bin) is a small gull also known as the fork-tailed gull. Its scientific name is Xema sabini. This bird is special because it's the only species in its group, called the genus Xema.

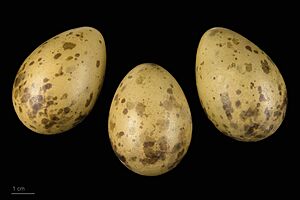

Sabine's gulls build their nests in groups, called colonies. They live on coasts and in cold, treeless areas called tundra. They lay two or three spotted, olive-brown eggs in a nest on the ground, made of grass. When it's not breeding season, these gulls live far out at sea, meaning they are pelagic. They eat many different kinds of animal food, especially small creatures they can catch.

Contents

What is a Sabine's Gull?

How Was the Sabine's Gull Discovered?

The Sabine's gull was officially described in 1819 by a scientist named Joseph Sabine. He based his description on birds collected by his brother, Captain Edward Sabine. Edward was on a trip with Captain John Ross to find the Northwest Passage.

They found these gulls nesting on small islands off the west coast of Greenland in July 1818. Later in 1819, another scientist, William Elford Leach, created the special group Xema just for this gull. The name Xema doesn't seem to have a specific meaning; it was likely just made up.

What Makes Sabine's Gulls Unique?

Sabine's gulls have a black beak with a yellow tip and a tail that looks like a fork. These features are very rare among gulls. Only the swallow-tailed gull from the Galapagos Islands shares them.

For a long time, people thought these two gulls were closely related. However, studies of their Mitochondrial DNA showed they are not. Scientists now believe the closest relative of the Sabine's gull is the ivory gull, another bird that lives in the Arctic. These two species likely separated about 2 million years ago.

Are There Different Types of Sabine's Gulls?

There are only small differences between Sabine's gulls from different places. Birds from Alaska might be a bit darker and larger. Most experts agree there's only one type of Sabine's gull.

However, some groups recognize four different types, called subspecies, based on their size and the color of their back. For example, the Handbook of the Birds of the World lists four:

- X. s. sabini: Found from the Canadian Arctic to Greenland.

- X. s. palaearctica: Lives from Spitsbergen to the Taymyr Peninsula in Russia.

- X. s. tschuktschorum: Breeds on the Chukotskiy Peninsula in Russia.

- X. s. woznesenskii: Found from the Gulf of Anadyr to Alaska.

Physical Features of the Sabine's Gull

Sabine's gulls are small birds. They are about 27 to 33 centimeters (11 to 13 inches) long. They weigh between 135 and 225 grams (4.8 to 7.9 ounces). Their wings are long, thin, and pointed, with a span of 81 to 87 centimeters (32 to 34 inches). Their bill is black with a yellow tip and is about 2.5 centimeters (1 inch) long.

How to Identify a Sabine's Gull

It's easy to spot a Sabine's gull because of its unique wing pattern. Adult gulls have a light grey back and wing feathers. Their main flight feathers are black, and their secondary feathers are white. Their white tail is forked, like a "V" shape.

During the breeding season, the male's head turns a dark color. Young gulls have a similar three-colored wing pattern. However, their grey parts are brown, and their tail has a black band at the end. It takes two years for young gulls to get their full adult feathers.

Molting and Calls

Sabine's gulls have an unusual way of changing their feathers, called molting. Young birds keep their first set of feathers through the autumn. They only start growing their first winter feathers after they reach their winter homes.

Adult gulls change all their feathers in the spring before they fly north. They have a partial molt in the autumn after returning to their winter areas. This is the opposite of what most gulls do. Sabine's gulls have a very high-pitched, squeaking call.

Where Do Sabine's Gulls Live?

Breeding and Migration Routes

Sabine's gulls breed in the Arctic region, all around the northern parts of North America and Asia. When autumn arrives, they fly south to warmer places. Most gulls from western North America spend winter at sea in the Pacific Ocean.

Some birds also travel to small islands and rocky areas off the west coast of South America. These include the Galápagos Islands. Here, the cold waters of the Humboldt Current provide a steady food supply. Along their journey, they stop along the US West Coast and the Pacific coasts of México and Central America. They have been seen in places like San Diego, California.

Atlantic Migration and Inland Sightings

Sabine's gulls from Greenland and eastern America usually fly across the Atlantic Ocean. They pass by the western coasts of Europe to spend winter off southwestern Africa. Here, they find cold waters from the Benguela Current. On their flight south, they stop at island chains like the Azores and Canary Islands.

Sometimes, Sabine's gulls are seen on other coastlines, like the northeastern United States. They can even be found further east along coastal Western Europe, especially after autumn storms. It's also common for Sabine's gulls to be seen inland in North America, Europe, and even Siberia. This shows they can migrate across continents, not just over the sea.

What Do Sabine's Gulls Eat?

The food that Sabine's gulls eat changes depending on the season and where they live. During the breeding season, they hunt for food in freshwater and on the land in the tundra. They also search in river deltas, estuaries, and coastal wetlands.

Their diet includes many different small creatures. They eat both land and water beetles, springtails, craneflies, mosquitoes, midges, flower flies, molluscs, insects, arachnids, water bugs, and various insect larvae. They also eat crustaceans and fish.

Sometimes, they will also eat the eggs or young chicks of other birds. This can include waterfowl, black turnstones, lapland longspurs, and even other gulls, including their own species. They usually eat these if they get the chance.