Shark finning facts for kids

Shark finning is when people cut off the fins from sharks and then throw the rest of the shark back into the ocean. This is against the law in many countries. Often, the sharks are still alive when they are thrown back. Without their fins, they cannot swim well. They sink to the bottom of the ocean and die because they can't breathe or are eaten by other animals.

Finning at sea helps fishing boats make more money. They only need to store and carry the fins, which are the most valuable part of the shark. The shark meat is big and heavy to transport. Many countries have now banned this practice. They require the whole shark to be brought back to port before its fins are removed.

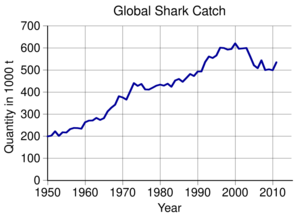

Shark finning became more common after 1997. This was mainly because more people wanted shark fins for shark fin soup and traditional medicines. This demand grew a lot in China as its economy got stronger. Better fishing tools and market prices also played a role. Now, there are even fake shark fin soups that don't use any real shark fins.

The Shark Specialist Group, part of the International Union for Conservation of Nature, says that shark finning is happening everywhere. They believe that the fast-growing and mostly uncontrolled trade in shark fins is a big danger to shark populations around the world. The global shark fin trade was worth between $540 million and $1.2 billion in 2007. Shark fins are among the most expensive seafood. They often sell for about $400 for one kilogram. In the United States, where finning is illegal, some people pay a lot for fins from whale sharks and basking sharks, sometimes $10,000 to $20,000 for just one fin.

The United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) reports that about 500,000 tonnes of sharks are caught each year. But many more sharks are caught without being reported. Shark finning has caused huge damage to the ocean's environment. About 73 to 100 million sharks are killed each year by finning. Many types of sharks are in danger because of this, including the scalloped hammerhead shark, which is critically endangered.

Contents

How Shark Finning Happens

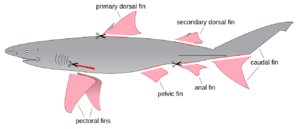

Almost all of a shark's fins are taken. This includes the fins on its back (dorsal fins), its side fins (pectoral fins), and its bottom fins (pelvic and anal fins). The bottom part of its tail (caudal fin) is also removed.

The rest of the shark's body is not worth much compared to its fins. So, sharks are sometimes finned while the fishing boats are still at sea. The shark, often still alive and without its fins, is thrown back into the ocean. This frees up space on the boat. When people talk about "shark finning" legally, they often mean this practice of removing fins from live sharks and throwing them back at sea. If fins are removed on land after the shark is caught, it might not be called "shark finning" in the same legal way.

Some of the shark species most often caught for their fins include:

- Blacktip shark

- Blue shark

- Bull shark

- Hammerhead shark

- Oceanic whitetip shark

- Porbeagle

- Shortfin mako shark

- Sandbar shark

- Silky shark

- Spinner shark

- Thresher shark

- Tiger shark

- Great white shark

Impacts of Shark Finning

On Individual Sharks

When sharks have their fins removed, they usually die. They can't move to push water through their gills, so they can't breathe. Or, they are eaten by other fish because they are helpless at the bottom of the ocean. Studies show that about 73 million sharks are finned each year. Some scientists think the number might be closer to 100 million. Most shark species grow slowly and don't have many babies. So, they can't reproduce fast enough to replace the number of sharks being killed.

On Shark Populations

Some studies say that between 26 and 73 million sharks are caught each year for their fins. The average number from 1996 to 2000 was 38 million. This is much higher than what the FAO reported, but lower than what many conservation groups estimate. In 2012, it was reported that 100 million sharks were caught globally.

Sharks grow slowly, become adults later, and have few offspring. These traits make them very sensitive to overfishing, like shark finning. Recent studies suggest that when there are fewer top predators like sharks, it can cause big changes in the ocean's food web.

The numbers of some shark species have dropped by as much as 80% in the last 50 years. Some groups say that shark fishing or "bycatch" (sharks caught by accident by other fisheries) is the main reason for this decline. They believe the market for fins has little impact. Bycatch might account for about 50% of all sharks caught. Others argue that the demand for shark fin soup is the main reason for the decline.

On Other Ocean Animals

Sharks are "apex predators," meaning they are at the top of the food chain. They have a big effect on marine systems, especially coral reefs. A report by WildAid explains how important these animals are.

Fins from sawfish are very popular in Asian markets and are some of the most valuable shark fins. Sawfishes are now highly protected under CITES, which is a global agreement to control trade in endangered species.

Live Science explained that too much shark fishing has serious effects on the entire ocean food chain. For example, a study found that when sharks were removed from a reef in the Caribbean, the number of carnivorous fish (fish that eat other fish) grew. These carnivorous fish then ate too many parrotfish, which usually keep the corals clean. Over time, the reefs changed from being full of coral to being covered in algae. We are still learning about the important role sharks play in the ocean.

How Vulnerable Are Sharks?

The IUCN Red List shows that 39 species of elasmobranches (sharks and rays) are threatened. This means they are either Critically Endangered, Endangered, or Vulnerable. Sharks are a key part of the ocean's health. They help keep the environment healthy by usually hunting sick, weak, and slower fish. Because of too much shark fishing in many parts of the world, sharks are disappearing or becoming endangered.

In 2013, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) listed how vulnerable sharks are.

Appendix I lists animals that are threatened with extinction. It includes:

- Requiem sharks (like Tiger Sharks, Bull Sharks)

- Hammerhead sharks

- Thresher sharks

- Basking sharks

- Mackerel sharks

- Eagle and mobulid rays

- Freshwater stingrays

- Whale sharks

- Sawfishes

Appendix II lists animals that are not yet threatened with extinction but might become so if trade is not carefully controlled. It includes:

As of 2014, five more species were added:

People Against Shark Finning

The crew of the Sea Shepherd conservation ship Ocean Warrior saw and photographed large-scale finning in Costa Rica's Cocos Island National Park. This practice is shown in the documentary Sharks: Stewards of the Reef. This film also looks at the cultural, money, and environmental effects of shark finning. Underwater photographer Richard Merritt saw live sharks being finned in Indonesia. He saw sharks without fins lying on the seabed, still alive, below the fishing boat. Finning has also been filmed in a protected marine area in the Raja Ampat islands of Indonesia.

Groups that care about animal welfare and animal rights strongly oppose finning. They say it is cruel because it leaves sharks with a big wound. This causes them to slowly die from hunger or by drowning. They also oppose it because finning is a major reason why shark populations are dropping so fast.

Shark finning is sometimes connected to organized crime groups. Opponents also worry about the health risks from eating shark fins. Fins can contain high levels of toxic mercury. A scientific group says that toxins build up in animals as they move up the food chain. Since sharks are large and live long, they are high on the food chain. This means they eat huge amounts of toxins that have built up in their prey.

About one-third of the fins imported to Hong Kong come from Europe. Spain is the biggest supplier, sending between 2,000 and 5,000 metric tons each year. Hong Kong handles at least 50%, and maybe up to 80%, of the world's shark fin trade. Major suppliers include Europe, Taiwan, Indonesia, and the United States.

The Australian naturalist Steve Irwin was known to leave Chinese restaurants if he saw shark fin soup on the menu. American chef Ken Hom points out that Western countries do little to protect fish like cod and sturgeon, even with all the concern about shark finning. However, he also stresses that it is wasteful to only harvest the fins.

In 2006, Canadian filmmaker Rob Stewart made a film called Sharkwater. It showed the shark fin industry in detail. In 2011, British chef Gordon Ramsay went to Costa Rica to investigate illegal shark fin trading. After looking into the shark fins, Ramsay was held at gunpoint and had gasoline poured on him by criminals.

According to WildAid, more people in China are against shark finning because of awareness campaigns. A 2008 survey in Beijing showed that 89% of people supported a ban on shark fins. A 2010 poll on Sina Weibo also showed strong support for a ban on shark fin sales. In an August 2013 survey in four Chinese cities, 91% of people supported a government ban on the shark fin trade.

Reporting on Shark Catches

Giam Choo Hoo, a member of the CITES Animals Committee and a representative of the shark fin industry in Singapore, claims that it is not common to kill sharks only for their fins while they are still alive. He says that most fins come from sharks after they have died.

However, researchers disagree with this claim. A 2006 study used trade data to estimate that between 26 and 73 million sharks are caught each year worldwide. This number, when converted to shark weight, was three to four times higher than the catches reported to the FAO. This difference might be because some shark catches are not recorded. It could also be because many sharks are finned and their bodies are thrown away at sea. Marine conservationists say that bringing sharks and rays to land with their fins still attached would help identify species. It would also improve official catch statistics and close loopholes in laws. Because remains are not always correctly identified, reports from scientists are not always reliable. Simply put, they say that the industry is either not reporting all the sharks caught each year, or it is often finning sharks at sea.

According to Shark Stewards, a non-profit environmental group, most shark fins go to Hong Kong for processing. Then, they are sent to China and other countries like the US. Fins traded as a dried product do not have any papers showing where the shark was caught, what species it was, or if it was caught legally or finned on the high seas. Because of this, many buyers do not know where the fin came from or if it was caught legally or illegally.

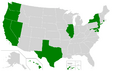

International Rules

In 2013, 27 countries and the European Union had banned shark finning. However, international waters are not regulated. International fishing groups are thinking about banning shark fishing and finning in the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. Finning is banned in the Eastern Pacific Ocean, but shark fishing and finning still happen a lot in most of the Pacific and Indian Oceans. In countries like Thailand and Singapore, public awareness campaigns about finning have reportedly reduced how many fins people buy by 25%.

There are four main types of rules:

- A shark sanctuary is an area where shark fishing is completely forbidden. This includes commercial fishing, accidental catches, and having, trading, or selling sharks and shark products. Even though these actions are banned, sharks can easily swim outside these protected areas without knowing it and be caught or finned. As of March 2018, there are 17 shark sanctuaries in the world.

- Maldives - 353,742 square miles (started in 2010)

- Palau - 233,317 square miles (started in 2009)

- Federated States of Micronesia - 1,155,448 square miles (started in 2015)

- Marshall Islands - 769,205 square miles (started in 2015)

- Samoa - 49,421 square miles (started in 2018)

- New Caledonia - 480,697 square miles (started in 2013)

- Cook Islands - 756,812 square miles (started in 2012)

- French Polynesia - 1,840,642 square miles (started in 2012)

- Honduras - 92,757 square miles (started in 2011)

- The Bahamas - 242,971 square miles (started in 2011)

- Dominican Republic - 104,050 square miles (started in 2017)

- Cayman Islands - 45,998 square miles (started in 2015)

- Bonaire - 3,747 square miles (started in 2015)

- British Virgin Islands - 30,933 square miles (started in 2014)

- St. Maarten - 193 square miles (started in 2016)

- Saba - 3,102 square miles (started in 2015)

- Areas where sharks must be brought to land with their fins still attached.

- Areas where rules are based on the ratio of fin weight to body weight.

- Areas with rules about trading shark products.

See also

In Spanish: Cercenamiento de las aletas de tiburón para niños

In Spanish: Cercenamiento de las aletas de tiburón para niños

- Chinese imperial cuisine

- Declawing of crabs

- Endangered sharks

- Pain in fish

- Shark culling

- Shark fin trading in Costa Rica

- Threatened sharks

Images for kids

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |