Slackware facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Slackware |

|

|---|---|

|

|

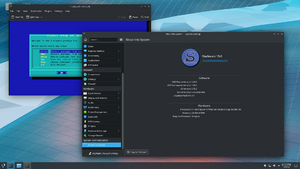

Slackware 15.0 with KDE Plasma 5 as the desktop environment

|

|

| Developer | Patrick Volkerding |

| OS family | Linux (Unix-like) (based on Softlanding Linux System) |

| Working state | Current |

| Source model | Open source |

| Initial release | 17 July 1993 |

| Latest release | 15.0 |

| Repository |

|

| Available in | Multilingual |

| Update method | pkgtool, slackpkg |

| Package manager | pkgtool, slackpkg |

| Supported platforms | IA-32, x86-64, ARM |

| Kernel type | Monolithic (Linux) |

| Userland | GNU |

| Default user interface |

CLI |

| License | GNU General Public License |

Slackware is a type of Linux distribution created by Patrick Volkerding in 1993. It was first based on another system called Softlanding Linux System (SLS). Slackware is special because it's one of the oldest Linux versions still being updated today. Many other Linux distributions, like early versions of SUSE Linux, were built using Slackware as a starting point.

Slackware is designed to be very stable and simple. It tries to be as much like Unix as possible. This means it doesn't change the original software much and lets users make most of the decisions. Unlike many modern Linux systems, Slackware doesn't have a fancy graphical installation. It also doesn't automatically find and install other programs that a new program might need. It uses simple text files and basic commands for setting things up. When you start it, it usually opens to a command-line interface, which is like a text-based screen where you type commands. Because of its simple and traditional approach, Slackware is often best for people who are already good with computers and Linux.

Slackware works on different computer types, including older 32-bit (IA-32) and newer 64-bit (x86_64) systems. There's also a version for ARM devices, which are often found in phones and small computers. Even though Slackware is mostly free and open-source software, it doesn't have a formal system for tracking bugs or a public place where its code is stored. Patrick Volkerding announces new versions when they are ready. He is the main person who works on new releases.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name "Slackware" came about because the project started as a fun side activity without serious plans. To keep it from being taken too seriously at first, Patrick Volkerding gave it a funny name. This name stuck even after Slackware became a big project.

The name "Slackware" is a nod to the "pursuit of Slack," which is a funny idea from a parody religion called the Church of the SubGenius. You can see hints of this humor in some Slackware pictures, like the pipe that the Linux mascot, Tux, is smoking. This is inspired by a character named J. R. "Bob" Dobbs.

You can also find a funny reference to the Church of the SubGenius in many of the install.end text files. These files tell the setup program when a software group has finished installing. In recent versions, like Slackware 14.1, this text is hidden using a simple code called ROT13.

How Slackware Started and Grew

The Beginning

Slackware began from the Softlanding Linux System (SLS). SLS was one of the most popular early Linux versions. It was the first to offer a wide range of software, not just the basic computer brain (kernel) and tools. This included a graphical interface called X11, internet tools like TCP/IP, and email tools like UUCP.

Patrick Volkerding started using SLS because he needed a LISP program for a school project. He found a LISP program called CLISP for Linux and downloaded SLS to run it. A few weeks later, his professor asked him to help install Linux at home and on school computers. Patrick had written down ways to fix problems he found in SLS. They used these notes to fix new installations, but it took a long time. So, the professor asked if the installation disks could be changed to include the fixes automatically. This was the start of Slackware. Patrick kept improving SLS by fixing bugs, updating software, and making installations smoother. Soon, he had updated about half of the programs beyond what SLS offered.

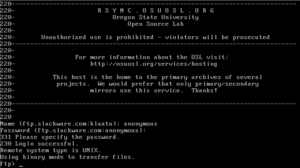

Patrick didn't plan to share his improved SLS with everyone. His friends at the university encouraged him to put his changes on an FTP server (a place to share files online). He thought SLS would release a new version with these fixes soon, so he waited. But many SLS users online were asking for a new release. So, Patrick finally posted a message asking, "Anyone want an SLS-like 0.99pl11A system?" He got many positive replies. After talking to the university's computer administrator, Patrick got permission to upload Slackware to their FTP server. The first Slackware version, 1.00, was released on July 17, 1993. It came on twenty-four 3.5-inch floppy disk images. After he announced it, so many people tried to download it that the server kept crashing! Soon after, a company called Walnut Creek CDROM offered more space on their FTP servers.

How Slackware Changed Over Time

Slackware quickly grew as more software was added. By version 2.1, released in October 1994, it had more than tripled in size, needing seventy-three 1.44 MB floppy disk images.

In 1999, Slackware's version number jumped from 4 to 7. Other Linux versions had higher numbers, and people thought Slackware was old even though its software was up-to-date. Patrick Volkerding decided to jump the version number to show that Slackware was current. He picked 7, guessing that other systems would soon reach that number.

In April 2004, Patrick Volkerding started including X.Org Server in the testing area of Slackware. This was meant to replace the older XFree86 software used for graphics. A month later, he officially switched to X.Org Server because most users preferred it and XFree86 was causing problems. Slackware 10.0 was the first version to use X.Org Server.

In March 2005, Patrick Volkerding announced that the GNOME desktop environment would be removed from Slackware. He had thought about this for a long time. He noted that other projects already offered better GNOME versions for Slackware than what Slackware itself provided. Patrick said that future GNOME support would depend on the community. The community responded, and by October 2016, several projects were actively providing GNOME (and similar desktop environments) for Slackware. These included Cinnamon, Dlackware, Dropline GNOME, MATE, and SlackMATE. This removal was a big deal for some in the Linux community because GNOME was very popular in many other Linux versions.

In May 2009, Patrick Volkerding announced a public test version of an official 64-bit Slackware, called Slackware64. This version was kept updated alongside the 32-bit version. Slackware64 is a pure 64-bit system, meaning it doesn't directly run or build 32-bit programs. However, it was designed to be "multilib-ready," which means it can be set up to run 32-bit programs with extra packages. Eric Hameleers, a key Slackware team member, created a special collection of packages to help convert Slackware64 to run 32-bit software. He started this 64-bit project while recovering from surgery in 2008. Patrick Volkerding tested it in December 2008 and was impressed by how much faster some programs ran (20 to 40 percent faster) compared to the 32-bit version. To make it easier to maintain both versions, Slackware's build scripts (called SlackBuilds) were changed to work for both 32-bit and 64-bit systems. Slackware64's first stable release was version 13.0.

Between the release of 14.1 in November 2013 and 14.2 in June 2016, there was a 31-month gap, the longest in Slackware's history. During this time, the development version didn't get updates for 47 days. However, on April 21, 2015, Patrick Volkerding apologized for the lack of updates and said the team used the time to do "some good work." Over 700 program changes were listed, including many big library updates. In January 2016, Patrick reluctantly added PulseAudio to Slackware. This was mainly because another program, BlueZ, stopped directly supporting ALSA (a sound system) in its newer versions, and other projects were dropping support for older BlueZ versions. Knowing some users wouldn't like the change, he joked that "Bug reports, complaints, and threats can go to me." These changes led to the release of Slackware 14.2 in June 2016.

How Slackware is Designed

Slackware's design focuses on simplicity, keeping software pure, and not changing the original source code much. Many of Slackware's design choices come from the simple nature of traditional Unix systems and follow the KISS principle (Keep It Simple, Stupid). In this case, "simple" means the system's design is straightforward, not that it's easy to use for everyone. So, how easy it is to use can depend on the person: those new to command-line tools might find it challenging, but users who know Unix might like its less complicated setup. To keep with Slackware's design, most software uses its original setup methods. However, for some system tasks, Slackware provides its own tools.

How Slackware is Developed

There isn't a formal system for tracking problems or an official way to become a developer. The project doesn't have a public place where its code is stored. Bug reports and contributions are handled in an informal way. All final decisions about what goes into a Slackware release are made by Patrick Volkerding, who is like the main leader of the project.

Patrick Volkerding developed the first versions of Slackware by himself. Starting with version 4.0, the official announcements listed David Cantrell and Logan Johnson as part of the "Slackware team." Later announcements, up to version 8.1, included Chris Lumens. Lumens, Johnson, and Cantrell also wrote the first official guide to Slackware Linux. The Slackware website mentions Chris Lumens and David Cantrell as "Slackware Alumni" who "worked full-time on the Slackware project for several years." In his notes for Slackware 10.0 and 10.1, Patrick thanked Eric Hameleers for his work on supporting wireless cards. Starting with version 12.0, a team began to form around Patrick again. According to the notes for 12.2, the development team had seven people. More people were added in future versions. Since version 13.0, Slackware seems to have a core team. Eric Hameleers shared insights into the core team in his essay "History of Slackware Development," written in October 2009, shortly after version 13.0 was released.

Software Packages

Managing Software

Slackware has its own set of tools for managing software, known as pkgtools. These tools can help you manage (pkgtool), install (installpkg), update (upgradepkg), and remove (removepkg) software packages from your computer. They can also unpack (explodepkg) and create (makepkg) packages. The official tool for updating Slackware over the internet is slackpkg. It was first created by Piter Punk as an unofficial way to keep Slackware updated. It became an official part of Slackware in version 12.2, after being included in the extras/ folder since Slackware 9.1. When you update a package, the new version is installed over the old one, and any files that are no longer needed are removed. Once a package is installed with slackpkg, you can manage it with pkgtool or other package commands. When you run upgradepkg, it only checks if the version numbers are different, so you can even go back to an older version if you want.

Slackware packages are tarballs (like compressed folders) that use different compression methods. Since version 13.0, most packages are compressed using xz, which makes them smaller. These files usually end with .txz. Before 13.0, packages were compressed using gzip and ended with .tgz. Slackware also supports bzip2 (.tbz) and lzip (.tlz) compression, but these are not used as often.

Packages contain all the files for a program, plus extra information files used by the package manager. The package tarball has the full folder structure of the files and is designed to be unpacked into the system's main folder (the root directory) during installation. The extra information files are in a special install/ folder inside the tarball. They usually include a slack-desc file, which is a text file that the package manager reads to show you a description of the software. There's also often a doinst.sh file, which is a script that runs after the package is unpacked. This script can create shortcuts, keep file permissions correct, handle new settings files, and do anything else needed for installation that can't be done just by copying files. During the development of version 15.0, Patrick Volkerding added support for a douninst.sh script. This script can run when a package is removed or updated, allowing package creators to run commands when their software is uninstalled.

The package manager keeps a local record of installed software on your computer, stored in several folders. On Slackware 14.2 and older systems, the main record of installed packages was kept in /var/log/. However, during the development of 15.0, Patrick Volkerding moved two of these folders to a special location under /var/lib/pkgtools/. This was done to prevent them from being accidentally deleted when system logs are cleared. Every Slackware installation will have packages/ and scripts/ folders in the main record location. In the packages/ folder, each installed package has a log file (named after the package, version, computer type, and build). This log file contains the package size (compressed and uncompressed), the software description, and the full path of all installed files. If the package had an optional doinst.sh script that ran after installation, the contents of that script are added to a file in the scripts/ folder, matching the package's name. This lets you view the post-installation script later. When a package is removed or updated, the old log files and scripts from packages/ and scripts/ are moved to removed_packages/ and removed_scripts/. This makes it possible to see what packages were previously installed and when they were removed. These "removed" directories were in /var/log/ on 14.2 and earlier, but were moved to /var/log/pkgtools/ during the development of 15.0. On systems that support the douninst.sh uninstall script, those scripts are stored in the /var/lib/pkgtools/douninst.sh/ folder while the package is installed. Once removed, the douninst.sh script is moved to /var/log/pkgtools/removed_uninstall_scripts/.

Finding Missing Software

Slackware's package system doesn't automatically find or manage "dependencies." Dependencies are other programs or libraries that a software needs to work. However, if you do the recommended full installation, all the dependencies for the standard Slackware programs are included. For custom installations or programs from other sources, Slackware expects you to make sure your system has all the necessary supporting programs. Since there are no official lists of dependencies for standard packages, if you install a custom setup or third-party software, you'll need to figure out any missing dependencies yourself. Because the package manager doesn't manage dependencies, it will install any package, whether or not its dependencies are met. You might only find out that dependencies are missing when you try to use the software.

While Slackware itself doesn't have official tools to resolve dependencies, some unofficial, community-made tools do. These are similar to how APT works for Debian-based systems or yum works for Red Hat-based systems. Some of these tools include:

- slapt-get is a command-line tool that works like APT. While slapt-get can help with dependencies, it doesn't do this for packages already in Slackware. However, several community package sources and Slackware-based systems use this feature. Gslapt is a graphical version of slapt-get.

- Swaret is a package management tool that can resolve dependencies. It was included as an optional package in Slackware 9.1 but didn't have dependency resolution then. It was removed from Slackware 10.0 and given to the community. It later added dependency resolution and the ability to undo changes. However, as of May 2014, no one is actively developing it.

- NetBSD's pkgsrc supports Slackware, among other Unix-like operating systems. pkgsrc can resolve dependencies for both ready-to-use programs and programs built from source code.

Where to Find Software

There are no official places (repositories) for Slackware software. The only official packages Slackware provides are on the installation disks. However, many third-party repositories exist for Slackware. Some are standalone, and others are for Linux versions based on Slackware but still work with Slackware packages. You can search many of these at once using pkgs.org, a Linux package search engine. But mixing and matching packages from different repositories can cause problems if two or more packages need different versions of the same dependency. This is called "dependency hell." Slackware itself won't help with these dependency issues. However, some projects provide a list of dependencies not included with Slackware, often in a file ending with .dep.

Because of possible dependency issues, many users choose to build their own programs using community-provided SlackBuilds. SlackBuilds are scripts that create an installable Slackware package from a software's original compressed file. Since SlackBuilds are scripts, they can do more than just compile a program's source code; they can also repackage pre-built programs from other projects or Linux versions into proper Slackware packages. SlackBuilds that compile from source have several benefits: you don't have to trust a third-party packager, and building locally allows for optimizations specific to your computer. Compared to manually building and installing software, SlackBuilds integrate programs more cleanly into the system using Slackware's package manager. Some repositories include both SlackBuilds and the resulting Slackware packages, letting users choose whether to build their own or install a pre-built one.

The only officially supported SlackBuilds repository is SlackBuilds.org, often called SBo. This is a community project that offers SlackBuilds for software not included with Slackware. Users can submit new SlackBuilds for software to the site. Once approved, they become the "package maintainer" and are responsible for updating the SlackBuilds to fix issues or build newer versions from the original creators. To make sure all programs can be built and used, any needed dependencies not included with Slackware must be listed and available on the site. All submissions are tested by the site's administrators before being added. The administrators want the build process to be very similar to how Slackware's official packages are built. This helps ensure that Patrick Volkerding is "sympathetic to our cause," meaning he's more likely to accept these SlackBuilds into official Slackware with few changes. It also stops users from suggesting that Patrick change his scripts to match SBo's. SBo provides templates for SlackBuilds and the extra information files, and they encourage maintainers to stick to them unless necessary.

Two Slackware team members, Eric Hameleers and Robby Workman, each have their own collections of pre-built packages, along with the SlackBuilds and source files used to create them. Most of these packages are extra software not in Slackware that they felt was worth maintaining. Some packages are used to test future Slackware updates. For example, Eric Hameleers provides "Ktown" packages for newer versions of KDE. He also maintains Slackware's "multilib" collection, which allows Slackware64 to run and build 32-bit packages.

New Versions of Slackware

Slackware releases new versions based on how many new features and how stable the system is, not on a fixed schedule like some other Linux versions (like Ubuntu). This means there's no set date for when a new version will come out. Patrick Volkerding releases the next version when he feels enough changes have been made from the previous one, and these changes make the system stable. As Patrick Volkerding has said, "It's usually our policy not to guess release dates, since that's what it is – pure guessing. It's not always possible to know how long it will take to make the needed updates and tie up all the loose ends. As things are built for the upcoming release, they'll be uploaded into the -current tree."

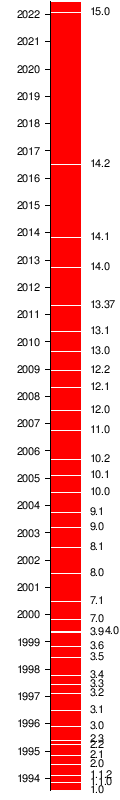

Throughout its history, Slackware generally aimed to release updated software at least once a year. From its start until 2014, Slackware had at least one release every year. There were many releases in 1994, 1995, 1997, and 1999, with three releases each year. After version 7.1 (June 22, 2000), releases became more regular, usually once a year. After that, only 2003, 2005, and 2008 had two releases. However, since Slackware 14.1 was released in 2013, new releases have slowed down a lot. There was more than a 2-year gap between 14.1 and 14.2, and over a 5-year gap until 15.0. When 15.0 was released, Patrick Volkerding said that Slackware 15.1 would hopefully have a much shorter development time because the "tricky parts" were solved during 15.0's development.

Slackware's most recent stable versions for 32-bit (x86) and 64-bit (x86_64) computers are at version 15.0, which was released on February 2, 2022. These versions include support for Linux 5.15.19.

Patrick Volkerding also keeps a testing/development version of Slackware called "-current." This version is for users who want the very latest updates. This version eventually becomes the next stable release. When that happens, Patrick starts a new "-current" version for the next Slackware release. While "-current" is usually stable, things can sometimes break, so it's not usually recommended for important computer systems.

| Version | Release date | End-of-life date | Kernel version | Notable changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.00 | 1993-07-17 | No EOL specified | 0.99.11 Alpha | |

| 1.1 | 1993-11-05 | No EOL specified | 0.99.13 | |

| 1.2 | 1994-03-19 | No EOL specified | 1.0.8 | |

| 2.0 | 1994-07-02 | No EOL specified | 1.0.9 | |

| 2.1 | 1994-10-31 | No EOL specified | 1.1.59 | |

| 2.2 | 1995-03-30 | No EOL specified | 1.2.1 | |

| 2.3 | 1995-05-24 | No EOL specified | 1.2.8 | |

| 3.0 | 1995-11-30 | No EOL specified | 1.2.13 | Changed from a.out to Executable and Linkable Format (ELF); first version on CD-ROM |

| 3.1 | 1996-06-03 | No EOL specified | 2.0.0 | Called "Slackware 96," like Windows 95 |

| 3.2 | 1997-02-17 | No EOL specified | 2.0.29 | |

| 3.3 | 1997-07-11 | No EOL specified | 2.0.30 | |

| 3.4 | 1997-10-14 | No EOL specified | 2.0.30 | Introduced ZipSlack |

| 3.5 | 1998-06-09 | No EOL specified | 2.0.34 | |

| 3.6 | 1998-10-28 | No EOL specified | 2.0.35 | |

| 3.9 | 1999-05-10 | No EOL specified | 2.0.37pre10 | |

| 4.0 | 1999-05-17 | No EOL specified | 2.2.6 | First version needing 1 GB for full install and added KDE |

| 7.0 | 1999-10-25 | No EOL specified | 2.2.13 | |

| 7.1 | 2000-06-22 | No EOL specified | 2.2.16 | Added GNOME |

| 8.0 | 2001-07-01 | No EOL specified | 2.2.19 | Added Mozilla Browser and optional Linux 2.4 |

| 8.1 | 2002-06-18 | 2012-08-01 | 2.4.18 | Changed package naming and improved setup tools |

| 9.0 | 2003-03-19 | 2012-08-01 | 2.4.20 (patched to 2.4.21) |

|

| 9.1 | 2003-09-26 | 2012-08-01 | 2.4.22 (patched to 2.4.26) |

Switched from OSS to ALSA for sound |

| 10.0 | 2004-06-23 | 2012-08-01 | 2.4.26 | Switched from XFree86 to X.org Server for graphics |

| 10.1 | 2005-02-02 | 2012-08-01 | 2.4.29 | |

| 10.2 | 2005-09-14 | 2012-08-01 | 2.4.31 | Removed GNOME desktop environment |

| 11.0 | 2006-10-02 | 2012-08-01 | 2.4.33.3 | First version offered on DVD |

| 12.0 | 2007-07-01 | 2012-08-01 | 2.6.21.5 | Switched from Linux 2.4 to 2.6, added support for HAL and removed floppy disk installation |

| 12.1 | 2008-05-02 | 2013-12-09 | 2.6.24.5 | |

| 12.2 | 2008-12-10 | 2013-12-09 | 2.6.27.7 (patched to 2.6.27.31) |

|

| 13.0 | 2009-08-26 | 2018-07-05 | 2.6.29.6 | Added 64-bit version, switched from KDE 3.5 to 4.x and changed to xz compressed packages |

| 13.1 | 2010-05-24 | 2018-07-05 | 2.6.33.4 | Added PolicyKit and ConsoleKit and switched to the libata system |

| 13.37 | 2011-04-27 | 2018-07-05 | 2.6.37.6 | Added support for GPT and tools for the Btrfs filesystem |

| 14.0 | 2012-09-28 | 2024-01-01 | 3.2.29 (patched to 3.2.98) |

Added NetworkManager and removed HAL |

| 14.1 | 2013-11-04 | 2024-01-01 | 3.10.17 (patched to 3.10.107) |

Added support for UEFI hardware and switched from MySQL to MariaDB. |

| 14.2 | 2016-06-30 | 2024-01-01 | 4.4.14 (patched to 4.4.301) |

Added PulseAudio and VDPAU and switched from udev to eudev and from ConsoleKit to ConsoleKit2 |

| 15.0 | 2022-02-02 | No EOL announced | 5.15.19 (patched to 5.15.187) |

Switched default text encoding to UTF-8, ConsoleKit2 to elogind, and KDE4 to Plasma5; moved to Python 3; moved package database; added lame, vulkansdk, SDL2, FFmpeg, PAM, and Wayland |

| -current | development | N/A | 6.12.25 | |

|

Legend:

Old version

Older version, still maintained

Latest version

Latest preview version

|

||||

Support for Older Versions

Slackware doesn't have a strict policy on how long it supports older versions. However, on June 14, 2012, announcements appeared that security updates would no longer be provided for versions 8.1, 9.0, 9.1, 10.0, 10.1, 10.2, 11.0, and 12.0, starting August 1, 2012. The oldest of these, version 8.1, had been supported for over 10 years before it reached its end-of-life (EOL). Later, on August 30, 2013, versions 12.1 and 12.2 were announced to reach EOL on December 9, 2013, having been supported for at least 5 years. On April 6, 2018, versions 13.0, 13.1, and 13.37 were declared EOL on July 5, 2018, after at least 7 years of support (13.0 had almost 9 years). On October 9, 2023, it was announced that versions 14.0, 14.1, and 14.2 would reach EOL on January 1, 2024.

While there were no official announcements for versions older than 8.1, they are no longer maintained and are considered EOL.

Different Computer Types

Historically, Slackware focused only on 32-bit computers (IA-32). However, starting with Slackware 13.0, a 64-bit version (x86_64) became available and is officially supported alongside the 32-bit version. Before Slackware64 was released, users who wanted a 64-bit system had to use unofficial versions like slamd64.

Slackware is also available for other computer types. There's Slack/390 for IBM S/390 computers and Slackware ARM (originally called 'ARMedslack') for ARM devices. Patrick Volkerding has called both of these "official." However, the S/390 version is still at version 10.0 (stable) and 11.0 (testing) and has not been updated since 2009. Also, on May 7, 2016, the developer of Slackware ARM announced that version 14.1 would reach EOL on September 1, 2016, and development of the "-current" version would stop with the release of 14.2. However, support for 14.2 would continue for the foreseeable future. The EOL announcement for 14.1 was added on June 25, 2016, and for 14.2 on December 21, 2022.

In July 2016, the Slackware ARM developer announced that the tools for developing and building the ARM version had been improved to make it easier to maintain. He also announced that a 32-bit version with hardware floating-point support was being developed. This version was released in August 2016 as a "current" (testing) version.

On December 28, 2020, work began on porting Slackware to the 64-bit ARM architecture (known as 'AArch64'). The first target computers were the PINE64's RockPro64 and Pinebook Pro. It was mostly finished by May 2021 and has many improvements over the original ARM version, especially in managing new computer models for the Slackware ARM community. The boot and installation processes were also greatly improved, making installation much easier.

On March 29, 2022, Slackware AArch64 was publicly released as a "-current" (development) version. It supports the RockPro64, Pinebook Pro, and Raspberry Pi 3 & 4. Online installation guides and video guides are available. The unofficial slarm64 project also has a version for AArch64 and an additional version for riscv64 computers.

In March 2022, official development of the 32-bit ARM version of Slackware stopped. Future development will focus only on the AArch64/ARM64 version. This was because 32-bit hardware couldn't keep up with Slackware's development and was slowing things down. Also, since most other major Linux versions stopped supporting 32-bit ARM, some applications couldn't be built or supported anymore. However, there is an unofficial Slackware version called BonSlack that provides both soft (ARMv5) and hard float (ARMv7) versions for 32-bit ARM. Its development and updates (from 14.2) match official Slackware. This project also offers versions for Aarch64 (ARM64), Alpha, HPPA (PA-RISC 1.1), LoongArch (64 bit), MIPS (32/64-bit), OpenRISC, PowerPC (32/64-bit), RISC-V (64-bit), S/390x, SH-4, SPARC (32/64-bit), and x86 (32-bit with 64-bit time_t) computers.

On December 21, 2022, Slackware ARM 14.2 was declared EOL (End of Life) as of March 1, 2023.

Slackintosh was a version of Slackware Linux for Macintosh New World ROM PowerPC computers. These were Apple's Power Macintosh, PowerBook, iMac, iBook, and Xserve lines from 1994 to 2006. The last version of Slackintosh was 12.1, released on June 7, 2008. The Slackintosh website is still active, and version 12.1 can be downloaded for older PowerPC Macintosh computers. In February 2012, the project developers announced that development was paused and that 12.1 would receive security updates for only one more month. The next month, it was announced that the stable release was frozen and would not get any more updates unless someone else took over. This never happened, and Patrick Volkerding officially declared the project finished in July 2021.

How to Get Slackware

Slackware 14.2 CD sets, single DVDs, and merchandise used to be available from a third-party Slackware store. However, due to payment issues, Patrick Volkerding "told them to take it down or I'd suspend the DNS for the store."

You can download Slackware ISO images (about 2.6 GB) for free from the official Slackware website. These can be downloaded using BitTorrent, FTP mirrors, or HTTP mirrors.

The Slackware version for IBM S/390 computers (which reached EOL in 2009) can still be downloaded. It can be installed from a DOS Partition or from a floppy disk.

The Slackware version for ARM computers can be downloaded and installed over a network using Das U-Boot and a TFTP boot server, or from a small root filesystem.

Slackware ARM can also be installed on a PC running QEMU using the same method.

Slackware AArch64 (ARM64) is installed directly from SD card images, similar to installing Slackware x86 from a DVD. It's also available as a general bootable EFI ISO.

See also

In Spanish: Slackware para niños

In Spanish: Slackware para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |