Slavery in the District of Columbia facts for kids

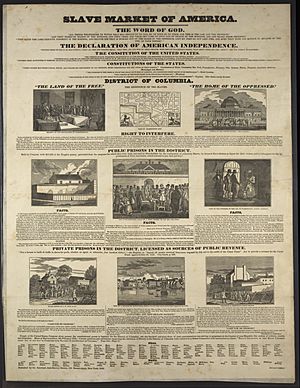

The slave trade in the District of Columbia was allowed by law from when the District was created until 1850. In 1850, a deal called the Compromise of 1850 made the buying and selling of enslaved people illegal in the District.

Knowing that rules about slavery were likely to change in the District was a big reason why the Virginia part of the District was given back to Virginia in 1847. This meant that large slave-trading businesses in Alexandria, like Franklin & Armfield, could keep operating in Virginia. In Virginia, slavery was more secure at that time.

Even after the slave trade was banned, owning enslaved people remained legal in the District. It wasn't until 1862, after many lawmakers from the Southern states left Congress to form the Confederacy, that Congress could pass the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act. This law offered some money, up to $300 per enslaved person, to owners who freed them. This money came from federal funds. Even though $300 was not a lot compared to what an enslaved person might have been worth before the war, it was the only time in the United States that slave owners received money for freeing their enslaved workers. Some owners, instead of freeing their enslaved workers for this small amount, took them to Maryland and sold them there, which was still legal.

People who wanted to end slavery, called abolitionists, believed that Congress had complete power over the laws in the District of Columbia, including laws about slavery. They argued that "States' rights" (the idea that states should have more power than the federal government) did not apply here. Southern lawmakers understood this. They had blocked efforts to end slavery in the District because they feared it would be the first step toward making slavery illegal everywhere in the country. The Emancipation Proclamation, which freed enslaved people in Confederate states, came five months after slavery ended in the District.

The effort to end slavery in the District of Columbia was a major part of the anti-slavery movement that led to the Civil War. Congress, led by former president John Quincy Adams (who was now a Representative from Massachusetts, a state strongly against slavery), received many requests to act on this issue. To stop these discussions, Congress passed "gag rules." These rules automatically put petitions aside, preventing them from being read, discussed, or printed. Instead of solving the problem, these rules made people in the North very angry and increased the division in the country over slavery.

Contents

- Enslaved Population in the District

- Slavery was Legal When D.C. Was Created

- Efforts to Ban Slavery in the District

- Early Attempts to End Slavery

- The Liberator Newspaper Speaks Out

- Reuben Crandall Trial (1836)

- Gag Rule (1836–1844)

- Massachusetts and Vermont Call for Action

- Virginia Retrocession (1847)

- Pearl Incident (1848)

- Slave Trade Banned (1850)

- Compensated Emancipation Act (1862)

Enslaved Population in the District

The number of enslaved people in the District of Columbia changed over time.

- From 1800 to 1820, the number of enslaved people grew.

- After 1820, the number started to decrease. The percentage of enslaved people in the total population also dropped quickly.

Let's look at the numbers from the U.S. Census:

- In 1820, the District had 33,039 people. About 67% were white (22,614), 12% were "free colored" (4,038), and 19% were enslaved (6,377).

- By 1850, Alexandria was no longer part of the District. The population was 73% white (37,941), 19% "free colored" (10,059), and 7% enslaved (3,687).

- In 1860, the percentages were 81% white (75,080), 15% "free colored" (11,131), and 4% enslaved (3,185).

Slavery was Legal When D.C. Was Created

When the District of Columbia was formed in 1801, slavery was legal in both Maryland and Virginia, the states from which the District's land was taken. Slavery remained legal in the District because no laws were made to ban it. Enslaved workers played a big role in building important structures like the White House, the U.S. Capitol, and other buildings in Washington. They also cleared land and built streets. Under most presidents, enslaved people also worked in the White House.

Efforts to Ban Slavery in the District

Before the Civil War, it was a common belief in the South that slavery was a matter for each state to decide. According to the Tenth Amendment, each state could choose whether to allow slavery and make its own laws about enslaved people and the slave trade.

The U.S. Constitution, in Article 1, Section 9, allowed states to "import...such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit," but only until 1808. This was the only restriction on slavery that the Constitution's writers could agree on. After 1808, a large trade in enslaved people developed between states. While the federal government could have regulated this "interstate commerce," there wasn't enough support in Congress, which was controlled by Southerners until 1861. Abolitionists wanted to end slavery completely, not just the trade between states.

Discussions about slavery often focused on two main questions:

- Would new states formed from the western territories, like those from the Louisiana Purchase and the formerly Mexican Southwest, be free states or slave states? This question was not settled until 1861. It led to violent conflicts, like the "Bleeding Kansas" period. During this time, Kansas had two governments, each claiming to be in charge, and two proposed constitutions—one for slavery and one against it. This period was like a "dress rehearsal" for the Civil War, led by "old" John Brown. Even though most Kansans clearly wanted their state to be free, the Southern lawmakers in Congress blocked it. Kansas finally joined the Union as a free state only after enough Southern lawmakers left Congress.

- The other question, which is less known today, was how to end slavery where it already existed. Besides the distant Utah Territory, the only place in the country where slavery existed but was not a state was the District of Columbia. The federal government had full control over the District. This meant that "States' rights" did not apply there. Because of this, abolitionists focused on the District, seeing it as the place where slavery was most vulnerable.

Early Attempts to End Slavery

In 1805, a representative named Mr. Sloan from New Jersey suggested in the House of Representatives that enslaved people in the District should be freed at a certain age. This idea was voted down without much discussion.

In 1828, citizens of the District also asked for slavery to be ended gradually, but their request was not successful.

The Liberator Newspaper Speaks Out

On January 1, 1831, William Lloyd Garrison started The Liberator, which became a very important newspaper for the American abolitionist movement. The very first article on the front page was a strong complaint about the District of Columbia:

The District is rotten with the plague, and stinks in the nostrils of the world. Though it is the Seat of our National Government, open to the daily inspection of foreign ambassadors, and ostensibly opulent with the congregated wisdom, virtue, and intelligence of the land, yet a fouler spot scarcely exists on earth. In it the worst features of slavery are exhibited; and as a mart for slave-traders, it is unequalled.

Garrison then included the text of a petition to Congress and told readers where they could sign a copy. The second article in the newspaper also focused on "The Slave Trade in the Capital."

Reuben Crandall Trial (1836)

Dr. Reuben Crandall was accused of giving out abolitionist writings in the District, which was against federal law. He had a jury trial and was found not guilty. This was the biggest criminal trial in the District at that time, with many reporters and members of Congress attending. The details from the trial were published and showed a lot about what life was like for enslaved people in the District. For example, police also worked as slave catchers, and owners often hired people to find and return enslaved people who had escaped.

Francis Scott Key, who wrote The Star-Spangled Banner, owned enslaved people and supported slavery. As the U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia, he was in charge of federal criminal cases. When slave catchers reported Crandall for having abolitionist literature, Key wrote a long accusation, charging him with "seditious libel and inciting slaves and free blacks to revolt."

Key thought this case would help his political career. Reuben's sister, Prudence Crandall, had started the first school for Black girls in the country, but it faced so much violence that she had to close it. However, Reuben's defense team showed that he had different views from his sister and had been confused with another abolitionist. The jury found him "not guilty." Key was publicly embarrassed, and it hurt his career.

Reuben's bail was set so high that he could not pay it, and he stayed in a damp Washington jail for over six months. He caught tuberculosis there and died soon after he was released.

Gag Rule (1836–1844)

Because so many petitions about slavery were arriving, the House of Representatives created a special committee. This committee, led by Representative Henry L. Pinckney of South Carolina, agreed with the House's view that Congress had no power to interfere with slavery in the District of Columbia or any state. To stop "the agitation of this subject," the committee suggested that "all petitions, memorials, resolutions, propositions, or papers, relating in any way, or to any extent whatever, to the subject of slavery, or the abolition of slavery, shall, without being either printed or referred, be laid upon the table, and that no further action whatever shall be had thereon." This rule passed by a vote of 117 to 68. This and similar "gag orders" were finally removed in 1844.

Massachusetts and Vermont Call for Action

In March 1840, both parts of the Massachusetts Legislature passed "Resolves" (Resolutions). These called for Congress to use its power from the Constitution to immediately end slavery and the slave trade in the District. They also wanted to ban the trade of enslaved people between states. This became the official position of Massachusetts. The state also officially opposed allowing any new slave states into the Union.

William Lloyd Garrison, who printed these important documents in his newspaper The Liberator, called this a victory. It was the first time any government in the United States had officially called for the immediate end of slavery. Vermont quickly followed Massachusetts' example.

Virginia Retrocession (1847)

In 1847, the part of the District of Columbia that had originally come from Virginia was given back to Virginia. This was called "retrocession." One reason for this was that Virginia wanted to make sure slavery could continue in Alexandria, which was a major slave-trading center.

Pearl Incident (1848)

In 1848, a large group of enslaved people tried to escape to freedom on a schooner (a type of boat) called the Pearl. This event, known as the Pearl incident, drew a lot of attention to slavery in the District and further fueled the anti-slavery movement.

Slave Trade Banned (1850)

The ban on the slave trade in the District of Columbia was a key part of the Compromise of 1850. This compromise was a series of laws passed by Congress to deal with the growing tensions over slavery.

Compensated Emancipation Act (1862)

Slave owners often complained that freeing their enslaved workers would take away their "property rights." "Property rights" was a polite way of talking about slavery during that time. The idea of compensated emancipation, where owners would be paid by the government for freeing their enslaved people, had been discussed for a long time. For example, England had used it to free enslaved people in its Caribbean colonies.

This idea became a real possibility in the United States after Southern senators and representatives left the U.S. Congress in 1861, and Abraham Lincoln became president. With Congress's support, Lincoln suggested compensated emancipation to the Union slave states, also called border states, like Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware. However, these states did not agree to any emancipation plan, whether compensated or not. Maryland freed its enslaved people in 1864, and Missouri in early 1865. But those in Delaware and Kentucky were not freed until the 13th Amendment was added to the Constitution in December 1865, seven months after the Civil War ended. Delaware symbolically approved the 13th Amendment in 1901, and Kentucky in 1975.

The District of Columbia was the only place in the United States where compensated emancipation actually happened. Under the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act, passed by Congress and signed by Lincoln in 1862, slavery was banned in the District. The federal government paid owners up to $300 (which is about $9,000 in 2023 money) for each freed person. Detailed records exist for each claim and payment. This maximum amount was much less than what a strong enslaved male could have been sold for before the war, especially if taken to Maryland or Virginia. However, the value of enslaved people decreased after the Civil War began. This was because it became impossible to transport enslaved people from northern "producer" states (like Maryland and Virginia) to Southern plantation owners. The growing chance of slavery being ended without any payment also lowered the value of enslaved people.

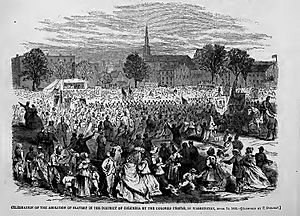

The day Lincoln signed the bill, April 16, 1862, is celebrated in the District as Emancipation Day. It has been a legal holiday there since 2005.

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |