History of slavery in Maryland facts for kids

Slavery in Maryland lasted for over 200 years. It began in 1642 when the first enslaved Africans arrived in St. Mary's City. Slavery ended in Maryland after the Civil War. Maryland was similar to its neighbor, Virginia, but slavery started to decline earlier here. By 1860, Maryland had the largest number of free Black people of any state.

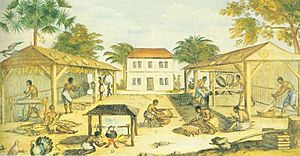

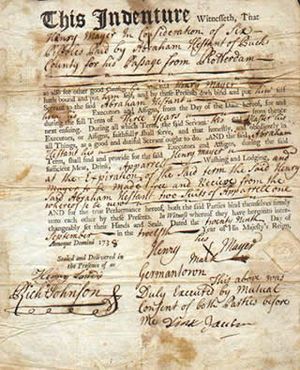

Early settlements in Maryland were often near rivers and waterways that flow into the Chesapeake Bay. Maryland farmers grew tobacco as their main crop because there was a high demand for it in Europe. Growing and processing tobacco needed a lot of workers. At first, many workers were indentured servants from England. These were people who agreed to work for a set time to pay for their trip to America. But as England's economy got better, fewer people came. So, Maryland colonists started bringing in enslaved Africans to meet the demand for labor.

By the 1700s, Maryland became a plantation colony, meaning it relied heavily on large farms worked by enslaved people. In 1700, Maryland had about 25,000 people. By 1750, this number grew to 130,000. By 1755, about 40% of Maryland's population was Black, mostly enslaved. These enslaved people lived mainly in the Tidewater areas where tobacco was grown. Farmers used the many rivers to transport their crops to the Atlantic coast for export. Baltimore became a very important port city.

After the Revolutionary War, some slaveholders in Maryland decided to free their enslaved people. Also, many free Black families had started during the colonial period. These were often mixed-race children born to white women and African men, who were born free. Even though laws were passed to limit freedom for Black people, by the time of the Civil War, almost half (49%) of Black people in Maryland were free. The total number of enslaved people had also been going down since 1810.

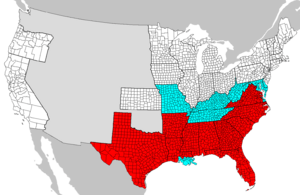

During the American Civil War, which was fought over slavery, Maryland stayed with the Union. However, some citizens, especially slaveholders, supported the Confederate States. Since Maryland was a Union border state, President Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation did not free enslaved people there. The next year, Maryland held a special meeting to change its laws. A new state constitution was approved on November 1, 1864. This new constitution made slavery illegal in Maryland. The right to vote was given to non-white men in the Maryland Constitution of 1867, which is still used today. (Women of all races got the right to vote in 1920).

Contents

The Start of Slavery in Maryland

Tobacco and Early Labor

From the very beginning, tobacco was the most important crop in Maryland. Tobacco was so important that it was even used as money when there weren't enough silver coins. A writer named John Ogilby noted in 1670 that people mostly traded goods instead of using money.

Since there was a lot of land and a growing demand for tobacco, there weren't enough workers, especially during harvest time. The first Africans brought to English North America arrived in Virginia in 1619. They were rescued by the Dutch from a Portuguese slave ship. These first Africans seemed to have been treated like indentured servants. Many Africans who came after them also gained their freedom after working for a certain time or by becoming Christian.

Some free Black people, like Anthony Johnson, became successful enough to own enslaved people or indentured servants themselves. This shows that in the 1600s, ideas about race were more flexible than they became later, when slavery became strictly based on race.

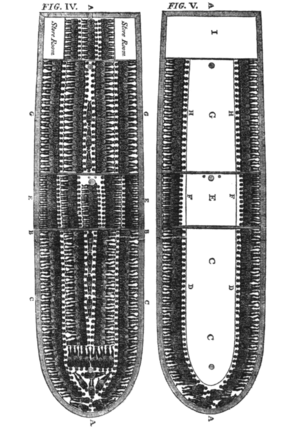

Bringing Enslaved Africans to Maryland

The first enslaved Africans arrived in Maryland in 1642. There were 13 of them at St. Mary's City, the first English settlement. At first, the legal status of Africans was unclear. They were not English citizens, so they were seen as foreigners. Colonial courts sometimes ruled that anyone who became Christian should be freed. To protect the rights of slaveholders, the colony passed laws to make things clear.

In 1661, the Maryland Assembly passed a law that specifically banned "miscegenation," which meant marriage between different races.

Maryland Makes Slavery Permanent

In 1664, under Governor Charles Calvert, 3rd Baron Baltimore, the Assembly made a very important rule. It said that all enslaved people would be slaves for life. It also said that children born to enslaved mothers would also be slaves for life. This law made slavery in Maryland continue on its own, as enslaved people had children. More enslaved people were also brought into Maryland until 1808.

By making the status of a child depend on the mother, Maryland followed a rule called partus sequitur ventrem. This was different from English law, where a child's status usually came from the father. In the colonies, if a mother was enslaved, her children were born into slavery, even if their father was white, English, or Christian.

The 1664 law mentioned "negroes and other slaves." This might mean that other groups, like Native Americans, were also enslaved in Maryland. Or it could refer to enslaved people of mixed African and European background. Many free families of color started during colonial times from relationships between free white women and men of African descent. Even though these mixed-race children were born free to white mothers, they were often forced to work as apprentices for many years.

In one unusual case, Nell Butler, an Irish indentured servant, married an enslaved African man. Because of the 1664 law, her indentured service was changed to slavery for life.

More laws followed, making slavery even stronger. In 1671, the Assembly passed a law saying that becoming Christian would not make an enslaved person free. Before this, some enslaved people had tried to sue for freedom after being baptized. This law was meant to encourage slaveholders to baptize their enslaved people without fear of losing them.

At this time, there were not many enslaved people in Maryland. Indentured servants from England were much more common. But the harsh slave laws became very important after large numbers of Africans began to be imported in the 1690s. In the late 1600s, the British economy improved, so fewer poor British people came to the colonies as servants. Also, a rebellion in Virginia in 1676 made plantation owners worry about having many poor white men who used to be servants. So, wealthy Maryland and Virginia planters started buying enslaved people instead of servants. By the end of the 1600s, most planters switched from using indentured servants to importing and enslaving African people.

Maryland in the 1700s

During the 1700s, the number of enslaved Africans brought to Maryland greatly increased. The tobacco economy needed many workers, and Maryland became a society built on slavery. In 1700, Maryland had about 25,000 people. By 1750, this number grew to 130,000. A large part of this population was enslaved. By 1755, about 40% of Maryland's people were Black, and most of them were enslaved. By the end of the century, the southern plantation counties had more enslaved people than free people.

In 1753, the Maryland assembly made another strict law. It stopped slaveholders from freeing their enslaved people on their own. A slaveholder who wanted to free someone had to get approval from the government for each person. This meant very few enslaved people were freed.

At this time, few white people in Maryland spoke out against slavery. Even poor white people who didn't own enslaved people often hoped to someday. Many white people in Maryland, and the South, believed in white supremacy. A French thinker named Montesquieu wrote in 1748 that people found it hard to believe enslaved Africans were truly human.

The Revolutionary War and Slavery

The main reason for the American Revolution was liberty, but this was mostly for white men. It did not include enslaved people, Native Americans, or women. The British, who needed more soldiers, tried to get African Americans to fight for them. They promised freedom in return. In 1775, the Royal Governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, promised freedom to servants and enslaved people who would join his Loyalist army.

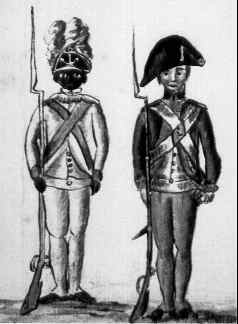

About 800 men joined Lord Dunmore's army. They wore the words "Liberty to Slaves" on their uniforms. Many of these soldiers later suffered from diseases like smallpox. Thousands of enslaved people in the South left their plantations to join the British. The British kept their promise and took about 3,000 freed enslaved people to Nova Scotia, where they were given land. Others went to Caribbean colonies or London.

The war did not change slavery much in general. The wealthy life of successful Maryland planters continued. A writer named Abbe Robin, who traveled through Maryland during the war, described the rich homes of important families. He noted their expensive furniture, fine horses, and carriages driven by "richly appareled slaves."

Enslaved labor made the plantation economy possible. An English observer wrote in the 1790s that enslaved workers moved slowly and seemed to sleep if their overseer wasn't watching. He said all their movement seemed forced.

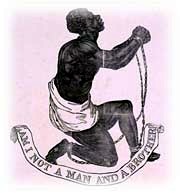

People Who Wanted to End Slavery

Methodists and Quakers

The American Revolution was fought for liberty. Many Marylanders who opposed slavery believed that Africans also deserved to be free. Methodists, especially, were against slavery for Christian reasons. In 1780, the National Methodist Conference in Baltimore officially spoke out against slavery. In 1784, the church even threatened to suspend Methodist preachers who owned enslaved people. This was a time of religious revival, and Methodists preached that all people were equal in spirit. They also allowed enslaved and free Black people to become preachers.

However, not all Methodists in the United States agreed on slavery. In the Southern states, most Methodist churches supported slavery. Ministers often used parts of the Old Testament to say that slavery was a natural part of life. Eventually, the Methodist Church split into two groups over the issue of slavery before the Civil War.

Some people used Bible verses from Leviticus to support slavery. They said that these verses allowed people to buy enslaved people from other nations. Other parts of the New Testament, like some writings by Paul, told enslaved people to obey their masters. After the Revolution, some in the South argued that slavery was good for enslaved people. They said that Christian planters could treat enslaved people well and protect them.

In the 1790s, Methodists and Quakers joined together to form the Maryland Society of the Abolition of Slavery. They asked the government to change laws. In 1796, they succeeded in getting rid of the 1753 law that stopped slaveholders from freeing their enslaved people. Because of the Methodists, Quakers, and the ideas of the Revolution, many slaveholders freed their enslaved people in the first 20 years after the war. In 1815, Methodists and Quakers formed the Protection Society of Maryland. This group worked to protect the growing number of free Black people in the state. By the Civil War, almost half (49.1%) of Black people in Maryland were free, especially in Baltimore.

The Catholic Church

Other churches in Maryland were not as clear on slavery. The Roman Catholic Church in Maryland had allowed slavery for a long time. Even though Jesuit missionaries believed in the spiritual equality of Black people, they still owned enslaved people on their plantations. The Catholic Church in Maryland supported slaveholding. The Jesuits owned six plantations with nearly 12,000 acres. In 1838, they sold their 272 enslaved people to sugar cane plantations in Louisiana. This was one of the largest sales of enslaved people in Maryland's history. The Jesuits' plantations were not making money, and they wanted to use their funds for schools in cities, like Georgetown College. Pope Gregory XVI spoke out strongly against slavery in 1839.

Famous Enslaved African-Americans in Maryland

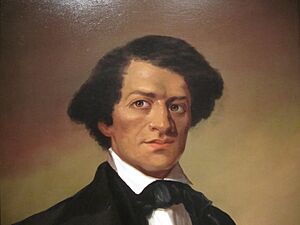

Frederick Douglass

After escaping slavery as a young man, Frederick Douglass stayed in the North. He became a very important voice for ending slavery and spoke widely about its wrongs. Douglass was born enslaved in Talbot County, Maryland, probably in 1818. He wrote about his childhood:

People whispered that my master was my father, but I don't know if that's true. My mother and I were separated when I was a baby. It was common in Maryland to separate children from their mothers very early. I don't remember ever seeing my mother during the day. She would lie down with me until I fell asleep, but she was gone long before I woke up.

Douglass wrote several books about his life. His 1845 book, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, powerfully described his experiences. It helped many people support the end of slavery.

Harriet Tubman

In 1822, Harriet Tubman was born enslaved in Dorchester County, Maryland. After escaping in 1849, she secretly returned to Maryland many times. She helped about 70 enslaved people, including her relatives, escape to freedom. She used the Underground Railroad for thirteen missions. Later, while working with the Union Army, Tubman helped over 700 enslaved people escape during a raid.

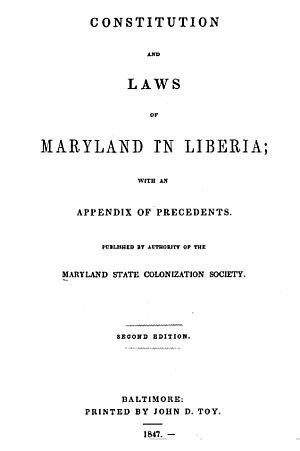

Maryland State Colonization Society

Some people worried about the challenges faced by free Black people and how their presence might affect slave societies. So, in 1817, planters and others formed the Maryland State Colonization Society. This group wanted to send all free African Americans to a colony in Africa. However, by this time, most enslaved and free Black people had been born in the United States. They wanted to gain their rights in the country they considered their home.

The American Colonization Society started the colony of Liberia in West Africa in 1821–22 for freed enslaved people. The Maryland State Colonization Society wanted its own territory. So, it founded the Republic of Maryland in West Africa, which was a short-lived independent state. In 1857, it became part of Liberia.

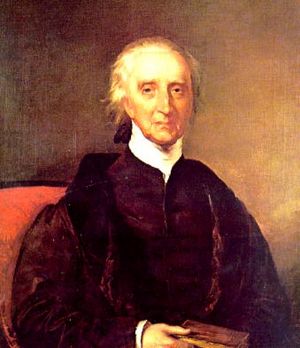

The society was founded in 1827. Its first president was Charles Carroll of Carrollton, a wealthy Catholic planter who owned many enslaved people. Although Carroll supported ending slavery slowly, he did not free his own enslaved people. He might have worried they would struggle to make a living in a society with discrimination. Carroll tried to pass a law for gradual abolition in Maryland, but it failed.

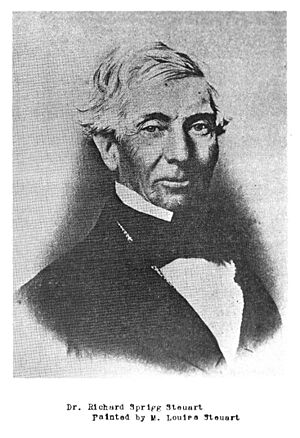

Many rich Maryland planters were members of this society. Among them were members of the Steuart family.

In 1845, Richard Sprigg Steuart wrote that Black people should "look to Africa, as his only hope of preservation and of happiness." He believed this would eventually lead to the removal of most African people from Maryland.

The society said its goal was "to be a remedy for slavery." In 1833, they stated that colonization would encourage slaveholders to free their enslaved people. They believed that enslaved people would be happier in Africa, and this would lead to slavery ending in Maryland.

Republic of Maryland in Africa

In December 1831, the Maryland state government set aside money to transport free Black people and formerly enslaved people to Africa. They planned to spend up to $20,000 a year, up to $200,000 total. Most of this money would be used to make the colony attractive to settlers. They offered free travel, housing, five acres of land for farming, and low-interest loans.

After a slave rebellion in Virginia in 1831, Maryland and other states passed laws that limited the freedoms of free people of color. Slaveholders feared their influence on enslaved societies. People who were freed were given a deadline to leave the state. They could only stay if a court found them to be of "extraordinary good conduct." Slaveholders who freed someone had to report it to the authorities.

In 1832, the government added more rules to encourage free Black people to leave. They could not vote, serve on juries, or hold public office. Unemployed free Black adults could be re-enslaved if they had no visible way to support themselves. Supporters of colonization hoped these rules would make free Black people want to leave the state.

John H. B. Latrobe, who led the Maryland State Colonization Society for 20 years, believed that settlers would be motivated by the "desire to better one's condition." He thought that eventually, "every free person of color" would be convinced to leave Maryland.

The Underground Railroad

For those who were tired of waiting for laws to change, there were illegal ways to escape. Enslaved people often escaped on their own, usually young men, as they could move more easily than women with children. Free Black people and white people who supported ending slavery slowly created safe places and guides. This network was called the Underground Railroad. It helped enslaved people reach freedom in Northern states. Maryland's many trails and waterways, especially the inlets of the Chesapeake Bay, offered many ways to escape by boat or land. Many people went to Pennsylvania, the closest free state. Supporters would hide refugees and give them food and clothing.

As more enslaved people tried to escape to the North, the reward for catching them grew. In 1806, the reward was $6. By 1833, it was $30. In 1844, a recaptured person could bring $15 if caught within 30 miles of their owner, and $50 if caught farther away.

Slavery in 1860

By the 1850s, few Marylanders still thought colonization was the answer to slavery. Even though one in six Maryland families still owned enslaved people, most owned only a few. Support for slavery varied depending on how important it was to the local economy. It remained very important to the plantations in Southern Maryland.

By 1860, almost half (49.1%) of all African Americans in Maryland were free. Maryland had nearly 84,000 free Black people in 1860, more than any other state. It had held this rank since 1810. Also, most Black people in Baltimore were free, and Baltimore had more free Black people than any other US city. Many planters in Maryland had freed their enslaved people after the Revolutionary War. Also, free Black families had existed since colonial times, often from relationships between free white women and African men. Their children were born free because their mothers were free.

Marylanders might have agreed that slavery should end, but they were slow to make it happen statewide. Even though fewer enslaved people were needed as tobacco farming declined, and some were sold to the Deep South, slavery was still too deeply rooted in Maryland society for wealthy white people to give it up easily. Rich planters had a lot of economic and political power. Slavery did not end until after the Civil War.

| Census Year |

1790 | 1800 | 1810 | 1820 | 1830 | 1840 | 1850 | 1860 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All States | 694,207 | 887,612 | 1,130,781 | 1,529,012 | 1,987,428 | 2,482,798 | 3,200,600 | 3,950,546 |

| Maryland | 103,036 | 105,635 | 111,502 | 107,398 | 102,994 | 89,737 | 90,368 | 87,189 |

The Civil War and Slavery's End

Leading Up to the War

Like other border states such as Kentucky and Missouri, Maryland's people were divided as the war approached. Some supported the North, and some the South. The western and northern parts of the state, especially those with German roots, had fewer enslaved people and wanted to stay in the Union. But the Tidewater Chesapeake Bay area, especially the three southern counties, relied on slavery and tended to support the Confederacy. After John Brown's raid in 1859, some citizens in slaveholding areas started forming local armies. Out of 687,000 people in 1860, about 60,000 men joined the Union army, and about 25,000 fought for the Confederacy. People's political feelings often matched their economic interests.

The first fighting of the Civil War happened on April 19, 1861, in Baltimore. Massachusetts troops were shot at by civilians. After this, Baltimore's Mayor and former Governor asked Maryland Governor Thomas H. Hicks to burn railroad bridges and cut telegraph lines to Baltimore. This was to stop more troops from entering the state. Governor Hicks, who owned enslaved people, reportedly agreed.

Maryland stayed part of the Union during the Civil War. This was thanks to President Abraham Lincoln's quick actions to stop unrest in the state. Governor Hicks's help, though late, also played an important role in preventing more violence and stopping Maryland from leaving the Union.

Maryland and the Emancipation Proclamation

Ending slavery was not certain at the start of the war. But events soon began to go against slaveholding interests in Maryland. In December 1861, a bill was proposed to free enslaved people in Washington, D.C.. In March 1862, Lincoln talked with Marylanders about ending slavery. Some, like Representative John W. Crisfield, argued that freedom would be worse for enslaved people. But these arguments became less effective as the war went on.

On April 10, 1862, Congress said the government would pay slaveholders who freed their enslaved people. Enslaved people in the District of Columbia were freed on April 16, 1862, and slaveholders were paid. In July 1862, Congress passed a law that allowed the Union army to enlist African-American soldiers. It also stopped the army from recapturing runaway enslaved people. That same month, Lincoln offered to buy out Maryland slaveholders, offering $300 for each freed person. But Crisfield rejected this offer.

On September 17, 1862, General Robert E. Lee's invasion of Maryland was stopped by the Union army at the Battle of Antietam. Five days later, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. This order declared all enslaved people in Southern states to be free. It went into effect in January 1863. However, Maryland, like other border states, was not included because it had stayed loyal to the Union.

Maryland remained a slave state, but things were changing. In 1863 and 1864, more and more enslaved people in Maryland left their plantations to join the Union Army. They accepted the promise of military service in return for freedom. This stopped slave auctions, as any enslaved person could avoid being sold by joining the army. In 1863, Crisfield lost his election to an abolitionist candidate, John Creswell. The Civil War was not over yet, but slavery in Maryland was finally coming to an end.

Slavery Ends in Maryland

The issue of slavery was finally addressed by the Maryland Constitution of 1864. This new document replaced the 1851 constitution. It was pushed by Union supporters who now controlled the state. Article 24 of the new constitution finally outlawed slavery.

Campaign to End Slavery

On December 16, 1863, a special meeting of the Union Party of Maryland was held. Thomas Swann, a state politician, proposed that the party work for "Immediate emancipation (of all slaves) in Maryland." John P. Kennedy, a respected politician and author, supported the idea. The motion passed. However, Marylanders were divided on the issue. So, a year of campaigning and lobbying followed across the state. Kennedy signed a party pamphlet calling for "immediate emancipation," which was widely shared.

On November 1, 1864, after a year-long debate, Marylanders voted on the slavery question. It was part of a larger vote on changes to the state constitution, but the slavery part was well known and hotly debated. The citizens of Maryland voted to abolish slavery. The vote was very close, with only about 1,000 votes making the difference. The southern part of the state, which relied heavily on slavery, voted against it.

The new constitution was approved on October 13, 1864. The vote was 30,174 to 29,799 (50.3% to 49.7%). The vote was won only after the votes of Maryland soldiers were counted. Marylanders serving in the Union Army voted overwhelmingly in favor (2,633 to 263).

Slavery in Maryland had lasted for just over 200 years, since it was first made legal in 1663.

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |