Spanish transition to democracy facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of Spain

Reino de España

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1975–1982 | |||||||||||

|

Flag

(1977–1981) Coat of arms

(1977–1981) |

|||||||||||

the Kingdom of Spain in 1975

|

|||||||||||

| Capital and largest city

|

Madrid | ||||||||||

| Official languages | Spanish After 1978: Catalan, Basque, Galician |

||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism (state religion until 1978) | ||||||||||

| Government | Unitary provisional absolute monarchy (1975–1978) Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy (after 1978) |

||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

|

• 1975–1982

|

Juan Carlos I | ||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||

|

• 1975–1976

|

Carlos Arias Navarro | ||||||||||

|

• 1976–1981

|

Adolfo Suárez | ||||||||||

|

• 1981–1982

|

Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Cortes Españolas (until 1977) Cortes Generales (from 1977) |

||||||||||

| Senate | |||||||||||

| Congress of Deputies | |||||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||||

|

• Death of Franco

|

20 November 1975 | ||||||||||

|

• Political Reform Act

|

18 November 1976 | ||||||||||

|

• 1977 Election

|

15 June 1977 | ||||||||||

|

• Amnesty Law

|

15 October 1977 | ||||||||||

| 29 December 1978 | |||||||||||

|

• 1979 Election

|

1 March 1979 | ||||||||||

| 23 February 1981 | |||||||||||

|

• 1982 Election

|

28 October 1982 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Spanish peseta | ||||||||||

| Calling code | +34 | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

The Spanish transition to democracy, known in Spain as la Transición, was a special time in modern Spanish history. It was when Spain changed from being a dictatorship (a country ruled by one person with total power) to a constitutional monarchy (a country with a king or queen, but where elected officials make the laws). This big change happened under Juan Carlos I, who became King.

This shift began after the dictator Francisco Franco died in November 1975. Historians have different ideas about when the transition officially ended. Some say it was after the 1977 election, while others believe it was when the 1978 Constitution was approved. Some even think it ended later, after a failed attempted coup in 1981. Most agree it was complete by the 1982 election, when power was peacefully handed over to a new party.

This period is often seen as a peaceful change. However, there was still some political violence from different groups. These included groups who wanted to separate from Spain, revolutionary groups, and others.

Contents

King Juan Carlos I's Role in Change

General Francisco Franco ruled Spain as a dictator from 1939 until his death in 1975. He had taken power after the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). In 1969, Franco chose Prince Juan Carlos, who was the grandson of Spain's last king, Alfonso XIII, to be his successor.

For six years, Prince Juan Carlos seemed to follow Franco's plans. But once he became King of Spain, he helped Spain become a constitutional monarchy. This was something his father, Don Juan de Borbón, had wanted since 1946.

This change was a big and important plan. It had a lot of support both inside and outside Spain. Countries like the United States and other Western governments wanted Spain to become a constitutional monarchy. Many Spanish and international business people also supported this idea.

However, the transition was not easy. Memories of the Civil War still worried many people. Supporters of Franco had strong backing in the Spanish Army. People on the left side of politics did not trust a king who had been chosen by Franco. For the transition to work, the army needed to stay out of politics. Also, the leftist groups needed to avoid causing trouble.

King Juan Carlos I started his rule by following Franco's old laws. He promised to uphold the rules of the Movimiento Nacional (National Movement), which was Franco's political system. He became king in front of the Francoist parliament, the Cortes Españolas. He also followed the old laws when choosing his first head of government. But in his first speech, he hinted that he wanted to change Spain's political system.

The King did not immediately choose a new prime minister. Instead, he kept Carlos Arias Navarro, who had been Franco's last prime minister. Arias Navarro did not plan to change the Francoist system much at first. He said his government wanted to continue Franco's ideas with a "democracy in the Spanish way." He thought political changes should be small. He wanted the parliament, the Cortes Españolas, to "update our laws as Franco would have wanted."

The government's reform plan was suggested by Manuel Fraga. It aimed for a "liberal democracy" like other Western European countries. This would happen through slow, controlled changes to the old laws. This plan was called "reform in continuity." It was mostly supported by those who wanted to keep Franco's social ideas.

For these reforms to succeed, they needed support from strong Franco supporters. These people were called the Búnker. They had a lot of power in the Cortes and other government bodies. Support was also needed from the Armed Forces and labor groups. The government also needed to calm down the groups who opposed Franco. These opposition groups were not part of the reform process. However, they were allowed to join politics more generally, except for the Communist Party of Spain (PCE).

A plan to change three main laws was created. But the exact changes would be decided by a special group. This meant that Fraga and other reformers lost some control over the laws. Still, a new Law of Assembly was passed in May 1976. This allowed public demonstrations with government permission. On the same day, a law allowing political groups was also approved. Adolfo Suárez supported this law, saying that if Spain was diverse, the parliament should not deny it. Suárez's support for this change surprised many, including King Juan Carlos I. This helped Juan Carlos decide to make Suárez the next Prime Minister.

The Arias-Fraga reform plan failed in June 1976. The Cortes rejected changes to the Criminal Code. This code had made it a crime to belong to any political party other than Franco's party. Members of the Cortes did not want to make the Communist Party legal. They added a rule that banned groups that "followed international rules" or "wanted a totalitarian regime" (a government with total control).

Adolfo Suárez's First Government (1976–1977)

Torcuato Fernández-Miranda, who was the head of the Council of the Realm, gave King Juan Carlos a list of three people to be the new prime minister. The King chose Adolfo Suárez. He felt Suárez could handle the difficult political changes ahead. Suárez needed to convince the Cortes, which was made up of Franco's politicians, to get rid of Franco's system. By working within the old legal system, he hoped to avoid the army getting involved. Suárez became the 138th Prime Minister of Spain on July 3, 1976. Many people on the left and some in the center did not like this choice because Suárez had been part of Franco's government.

As Prime Minister, Suárez quickly set out a clear plan:

- Create a Law for Political Reform. Once approved by the Cortes and the public, this law would start the process of creating a liberal democracy in Spain.

- Call for democratic elections in June 1977. These elections would choose a new parliament to write a new democratic constitution.

This plan was clear, but it was very challenging. Suárez had to convince the opposition to join his plan. He also had to make sure the army would not stop the process. At the same time, he needed to control the situation in the Basque Country.

Despite these challenges, Suárez's plan moved forward quickly between July 1976 and June 1977. He worked on many different things during this short time to reach his goals.

The idea for the Political Reform Act was written by Torcuato Fernández-Miranda. He gave it to Suárez's government in July 1976. The government approved it in September 1976. To create a parliamentary democracy, this law had to dismantle Franco's system using the Francoist Cortes itself. The Cortes debated this law in November. It was finally approved with many votes in favor.

Suárez's government wanted the public to support these changes. So, they held a public vote (a referendum) on December 15, 1976. A large majority of voters (94%) supported the changes. After this, the process for holding elections began. These elections would choose the members of the Constituent Cortes, who would write a new democratic constitution.

With this part of his plan done, Suárez had to decide if he should include the opposition groups who had not been involved earlier. He also had to deal with the groups who had opposed Franco.

Suárez's Government and the Opposition

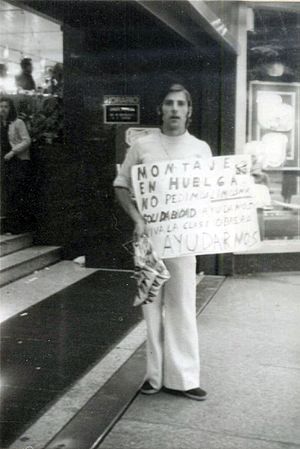

Suárez took steps to make his plan more believable. He allowed some political prisoners to be freed in July 1976. He then freed more in March 1977 and granted a full political amnesty in May of that year. In December 1976, the Tribunal de Orden Público (TOP), a Francoist secret police group, was shut down. The right to strike was made legal in March 1977. The right to form unions was given the next month. Also in March, a new election law was passed. This law made Spain's election system similar to other democratic countries.

Through these actions, Suárez met the demands that opposition groups had made since 1974. These groups met in November 1976 to form a platform of democratic organizations.

Suárez started talking with the opposition by meeting with Felipe González, the leader of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE), in August 1976. The socialist leader's positive attitude helped Suárez move his plan forward. But everyone knew that making the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) legal would be the biggest challenge. The PCE had more members and was better organized than any other opposition group. However, in a meeting with military leaders in September, the officers strongly opposed legalizing the PCE.

The PCE, for its part, became more public with its views. They said the Law for Political Reform was not democratic. They believed the elections for the Constituent Cortes should be called by a temporary government that included opposition groups. The opposition was not very excited about the Law for Political Reform. Suárez had to take more risks to get the opposition groups to join his plan.

In December 1976, the PSOE held a meeting in Madrid. They began to distance themselves from the PCE's demands. They said they would take part in the upcoming elections for the Constituent Cortes. In early 1977, Suárez faced the problem of legalizing the PCE. After a tragic event in January 1977 against trade unionists and Communists (the Massacre of Atocha), Suárez spoke with PCE leader Santiago Carrillo in February. Carrillo was willing to cooperate without making demands. He also offered a "social pact" for after the elections. This pushed Suárez to take the riskiest step of the transition: legalizing the PCE in April 1977. During this time, the government also started to support the Socialist union, the Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT), more than the Communist-leaning CCOO. This helped to limit radical opposition and shaped how labor relations developed in Spain.

Suárez's Government and the Spanish Army

Adolfo Suárez knew that the Búnker—a group of strong Franco supporters—had close ties with army officials. This group could stop political reform.

To handle this, Suárez wanted to rely on a more liberal group within the military. He gave important positions to members of this group. General Manuel Gutiérrez Mellado was a key figure in this faction. However, in July 1976, the Vice President for Defense Affairs was General Fernando de Santiago, who was a hardliner. De Santiago had shown his opposition before, during the first amnesty. He also opposed the law allowing unions. Suárez dismissed Fernando de Santiago and appointed Gutiérrez Mellado instead. This caused many in the army to oppose Suárez, especially when the PCE was legalized.

Meanwhile, Gutiérrez Mellado promoted officers who supported political reform. He removed commanders of the security forces (the Policía Armada and the Guardia Civil) who seemed to want to keep Franco's system.

Suárez wanted to show the army that making the country democratic would not lead to chaos or revolution. He had help from Santiago Carrillo for this. But he could not count on help from terrorist groups.

Rise in Terrorist Activity

The Basque Country was often in a state of unrest during this time. Suárez offered amnesties for many Basque political prisoners. However, clashes continued between police and protesters. The separatist group ETA had seemed open to a truce after Franco's death in mid-1976. But they started armed attacks again in October. The years from 1978 to 1980 would be ETA's deadliest. However, between December 1976 and January 1977, a series of attacks caused high tension in Spain.

The Maoist group GRAPO began its armed struggle by bombing public places. They then kidnapped two important figures: the President of the Council of the State, José María de Oriol, and General Villaescusa. From the right, members of the neo-fascist Alianza Apostólica Anticomunista carried out the Atocha massacre in January 1977. This violent attack targeted labor lawyers in Madrid.

During these difficult times, Suárez met with many opposition leaders. They all condemned terrorism and supported Suárez's actions. The Búnker group used this instability to claim the country was falling into chaos.

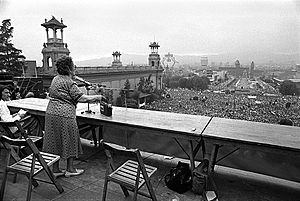

Despite the increased violence from ETA and GRAPO, elections for the Constituent Cortes were held in June 1977.

First Elections and the Constitution

The elections held on June 15, 1977, showed that four main political parties had strong support across the country:

- Union of the Democratic Centre (UCD): 34.61% of votes

- Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE): 29.27% of votes

- Communist Party of Spain (PCE): 9.38% of votes

- People's Alliance (AP): 8.33% of votes

The Basque Nationalist Party (EAJ/PNV) and the Democratic Pact for Catalonia (PDC) also did well in their regions. This showed that nationalist parties were gaining political strength.

The Constituent Cortes (the elected Spanish parliament) then began to write a new constitution in mid-1977. In 1978, the Moncloa Pact was signed. This was an agreement between politicians, parties, and unions. It helped plan how to manage the economy during the transition. The Spanish Constitution of 1978 was then approved by a public vote on December 6, 1978.

UCD Governments

Prime Minister Adolfo Suárez's party, the UCD, won the most votes in the June 1977 and March 1979 elections. However, they did not win a full majority. To govern, the UCD had to form alliances with other parties. From 1979, the government spent a lot of time trying to keep its many groups and alliances together. By 1980, Suárez's government had mostly achieved its goal of moving to democracy. It did not have a clear plan for what to do next. Many UCD members were quite conservative and did not want more changes. For example, a law to make divorce legal caused a lot of disagreement within the UCD, even though most people supported it. The UCD alliance started to fall apart.

Disagreements within the party weakened Suárez's power. This tension led to Suárez resigning as head of government in 1981. Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo was then chosen to lead the new government and the UCD party. Some members, like the social democrats, left the UCD and later joined the PSOE. Other members, the Christian democrats, left to form a new party.

While the move to democracy convinced one part of ETA (ETA-pm) to stop fighting and join politics, it did not stop attacks by another part of ETA (ETA Military) or GRAPO. Meanwhile, some parts of the army were restless, causing fear of a military coup. On February 23, 1981, some army members tried to stage a coup, known as 23-F. Lieutenant Colonel Antonio Tejero led a group of Guardia Civil to take over the Congress of Deputies. The coup leaders claimed they were acting for the king. However, early the next morning, King Juan Carlos gave a speech on TV. He clearly opposed the coup. He said the Crown would not allow anyone to use force to stop the democratic process. The coup failed later that day. But it showed that some parts of the army still wanted to stop democracy.

Felipe González's First Government (1982–1986)

Calvo Sotelo ended parliament and called for elections in October 1982. In the 1979 election, the UCD had won the most votes. But in 1982, they lost badly, winning only 11 seats. The 1982 elections gave a clear majority to the PSOE. This party had been preparing for years to become the next government.

At a PSOE meeting in May 1979, leader Felipe González resigned. He did not want to work with the strong revolutionary groups in the party. A special meeting was called in September. The party then became more moderate, giving up some of its older ideas. This allowed González to lead again.

Throughout 1982, the PSOE confirmed its moderate direction. They also brought in the social democrats who had left the UCD.

The PSOE won a clear majority in parliament in two elections (1982 and 1986). They also won exactly half the seats in 1989. This allowed the PSOE to make laws and govern without needing to form alliances with other parties. This way, the PSOE could pass laws to achieve its political program, called "el cambio" ("the change"). The PSOE also led many local and regional governments. This strong political majority gave Spain a long period of peace and stability after the intense years of the transition.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Transición española para niños

In Spanish: Transición española para niños

- Greek transition to democracy (Metapolitefsi)

- Chilean transition to democracy

- Portuguese transition to democracy

- Spanish 1977 Amnesty Law

- Spanish society after the democratic transition

- Turno pacífico

- Franquismo sociológico

- Constitution of Spain

- José Larrañaga Arenas

- Almería Case