Stefan Lochner facts for kids

Stefan Lochner (also known as the Dombild Master or Master Stefan; born around 1410 – died late 1451) was an important German painter. He worked during the end of the International Gothic art period. His paintings mix the long, flowing lines and bright colors of that time with the realistic details, amazing paint textures, and new ideas of the early Northern Renaissance.

Lochner lived in Cologne, which was a busy city for trade and art in northern Europe. He was one of the most important German painters before Albrecht Dürer. His surviving artworks include single oil paintings, religious polyptychs (paintings with many panels), and illuminated manuscripts (decorated books). These often show angels with blue wings and a dreamy look. Today, experts are sure that about 37 individual paintings are by him.

We don't know much about Lochner's life. Art historians believe he was born in Meersburg, Germany, around 1410. They think he might have learned some of his skills in the Netherlands. Records show that his career grew quickly but ended early because he died young.

Around 1442, the city council of Cologne asked him to create decorations for a visit from Emperor Frederick III. This was a very important event for the city. Records from the next few years show that he became wealthy and bought several properties in Cologne. However, he later seemed to spend too much and got into debt. The Plague hit Cologne in 1451. After this, records of Stefan Lochner stop, except for mentions by people he owed money to. It is thought he died that year, when he was about 40 years old.

Lochner's identity and fame were forgotten until the early 1800s, when people became interested in 15th-century art again. Even with a lot of research, it's still hard to be sure which paintings are his. For many years, several related artworks were grouped together and simply called the "Dombild Master." This name came from the Dombild Altarpiece (meaning "cathedral picture"), which is still in Cologne Cathedral.

A diary entry by Dürer, written 400 years later, helped experts in the 1900s figure out Lochner's true identity. Only two of his known works have dates, and none are signed. He greatly influenced many artists who came after him in northern Europe. Besides the many copies made in the late 1400s, you can see parts of his style in paintings by Rogier van der Weyden and Hans Memling. Famous writers like Friedrich Schlegel and Goethe praised Lochner's art, especially the "sweetness and grace" of his Madonnas (paintings of Mary).

Contents

Life of Stefan Lochner

We know about Stefan Lochner's life from a few old records. These records mostly talk about art jobs, payments, and buying and selling property. We don't have any documents about his early life. This is partly because many old records from his likely birthplace were lost during the French occupation of Cologne.

The main records about Lochner's life include:

- A payment from the city of Cologne in June 1442 for decorations for Emperor Frederick III's visit.

- Documents from October 1442 and August 1444 about him owning a house in Roggendorf.

- Documents from October 1444 for buying two houses in St. Alban.

- His registration as a citizen of Cologne on June 24, 1447.

- His election to the city council in December 1447.

- His re-election to that job at Christmas 1450.

- Letters with the city council in August 1451.

- An announcement on September 22, 1451, about a plague graveyard being set up near his property.

- Court records from January 7, 1452, about his property being taken by creditors.

Where Did He Grow Up?

Based on a few clues, it's believed Lochner came from Meersburg, a town near Lake Constance. His parents, Georg and Alhet Lochner, were citizens there and died in 1451. Some documents from 1444 and 1448 mention a "Stefan" as "Stefan Lochner of Constance." However, there's no proof he lived there, and his art style doesn't look like art from that area. There are no other records of him or his family in Meersburg, except for a mention of people named Lochner (which is a rare name) in Hagnau, a village close to Meersburg.

Records suggest that Lochner's artistic talent was noticed early on. He might have been from the Netherlands or worked there for a master, possibly Robert Campin. Lochner's art seems to be influenced by Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden. You can see parts of their styles in the way Lochner structured and colored his later works, especially his Last Judgement. However, it's not thought that he studied directly with either of them.

Moving to Cologne and Becoming Famous

By the 1440s, Cologne was the biggest and richest city in the Holy Roman Empire. It controlled and taxed trade moving from Flanders to Saxony. This made it a major center for money, religion, and art. The city had a long history of creating high-quality art. In the 1300s, its art was considered as good as that from Vienna and Prague. Artists in Cologne focused on more personal and gentle subjects. The area became known for small paintings that had "great lyrical charm and loveliness," showing the deep religious feelings of German mystics.

In the 1430s, painting in Cologne had become a bit old-fashioned. It was still influenced by the style of the Master of Saint Veronica, who was active until 1420. When Lochner arrived, he had already seen the work of Netherlandish painters and was using oil paints. He quickly became more popular than other artists in the city. Art historian Emmy Wellesz said that after Lochner came, "painting in Cologne became filled with new life." This was probably because he had seen the work of Netherlandish artists earlier. He became widely known as the most skilled and modern painter in the city, where people called him "Maister Steffan zu Cöln."

Lochner first appears in records in 1442, nine years before he died. He moved to Cologne and got a job from the city council. He was asked to provide decorations for the visit of Emperor Frederick III. Lochner seemed to be well-known already. Even though other artists helped prepare for the event, he was in charge of the most important arrangements. The main artwork seems to have been the Dombild Altarpiece. Modern art historians call it "the most important art job of the fifteenth century in Cologne." Records show he was paid 40 marks and 10 shillings for his work.

Lochner bought a house with his wife, Lysbeth, around 1442. We don't know anything else about her, and it seems they had no children. In 1444, he bought two bigger properties: the "zome Carbunckel" near Saint Alban Church, and the "zome Alden Gryne." Historians wonder if he needed these bigger places to house more assistants because his business was growing. He likely lived in one house and worked in the other. These purchases might have caused money problems. Around 1447, he seemed to have financial difficulties and had to mortgage his homes. He took out second mortgages in 1448.

Plague and His Death

In 1447, the local painters' guild chose Lochner to be their representative on the city council, called a Ratsherr. This means he must have lived in Cologne since at least 1437, because only people who had lived in the city for ten years could take this job. He hadn't become a citizen right away, possibly to avoid paying the 12 guilder fee. He had to be a Ratsherr, and on June 24, 1447, he became a citizen of Cologne. The role of city councilor could only be held for one year, and then you had to wait two years before doing it again. Lochner was chosen for a second term in the winter of 1450–51 but died while still in office.

There was an outbreak of the plague in 1451. We have no records of him after Christmas of that year. On August 16, 1451, officials in Cologne told the council of Meersburg that Lochner could not deal with the will and property of his parents, who had recently died. It's thought he was already sick by then, as the plague was widespread in the area. Lochner died sometime between this date and December 1451, when people he owed money to took possession of his house. Records from 1451 don't mention Lysbeth, so she was probably already dead.

Lochner's Art Style

Lochner worked in the late International Gothic style, which was already seen as a bit old-fashioned by the 1440s. However, he is still considered very creative. He brought many new ideas to painting in Cologne. For example, he filled his backgrounds and landscapes with specific and detailed elements. He also made his figures look more solid and real. Wellesz described his paintings as showing "an intensity of feeling which gives a very special and very moving quality to his work." She added that his deep religious feeling is seen in his figures and in the "pure and glowing colours."

Lochner painted with oil paints. He prepared his painting surfaces in a way common for other artists in North Germany. For some works, he put canvas on the wooden panel before adding the usual chalk base. He probably did this when there were large areas to be covered in plain gilding (gold leaf). If the gold ground was meant to have a pattern, like a brocade, he carved this design into the chalk base before applying the gold. In some paintings, he even added molded parts to raise the surface before gilding.

He used different ways to apply gold to create various effects. He would lay the gold leaf with water for shiny, polished areas. For more decorative parts, he used oil or varnish sizing (a sticky layer) to apply the gold. His colors are usually bright and glowing, with many shades of red, blue, and green. He often used ultramarine, which was very expensive and hard to get back then. His figures are often outlined with red paint.

He was also innovative in how he painted skin tones. He built them up using lead whites to create pale complexions that looked almost like porcelain. This style connects to an older tradition of showing noble women. Their paleness suggested a life spent indoors, "protected from working in the fields, which was what most people did." This technique especially followed the Master of Veronica, though that earlier painter's figures had a yellowish, ivory look. Lochner's Madonnas are often dressed in rich blues that stand out against surrounding yellow, red, and green paints. According to art historian James Snyder, the artist "used these four basic colors for his harmonies." But he also used softer, deeper colors in a technique called "pure color."

Like Conrad von Soest, Lochner often used black cross-hatching on gold. He did this usually for metal objects like brooches, crowns, or buckles. This was to imitate the work of goldsmiths on precious items like reliquaries and chalices. He was greatly influenced by metalwork and goldsmithing, especially in how he painted gold backgrounds. Some people think he might have trained as a goldsmith himself. You can see how he copied parts of their craft even in his underdrawings (the first sketch on the canvas). Good examples include the detailed gold border of the angels in his Last Judgement and Gabriel's clasp on the outer wing of the Dombild altarpiece.

Lochner seemed to prepare his drawings on paper before doing the underdrawings on the panel. There's little sign of him changing things, even when placing large groups of figures. Infrared reflectography of the underdrawings for the Last Judgement panels shows letters used to mark the final color to be applied. For example, 'g' for gelb (yellow) or 'w' for weiss (white). There are few differences in the finished work. He often moved drapery fold lines or changed the size of figures to show perspective. The underdrawings show a skilled, lively, and confident artist. The figures look fully formed with little sign of changes. Many are very detailed and precisely shaped, like St Ursula's brooch in the Altarpiece of the City Patron Saints, which has very detailed garlands and diadems.

Perhaps influenced by van Eyck's Madonna in the Church, Lochner paid close attention to how light fell and changed. According to art historian Brigitte Corley, the clothes of his characters "change their hues in delicate reaction to the influx of light." Reds turn into pinks and then a dusty grayish white, greens become a warm pale yellow, and lemon shades go through oranges to a rich red. Lochner used the idea of supernatural light not just from van Eyck, but also from von Soest's Crucifixion. In that painting, light from Christ fades around John's red robe, as yellow rays eventually become white. It's possible that some of the faces of saints are modeled after real people. These could be donor portraits of the people who ordered the paintings and their wives. Figures that fit this idea include St Ursula and St Gereon from the City Saints altarpiece.

Unlike painters in the Netherlands, Lochner wasn't as focused on showing perspective. His pictures are often set in a shallow space, and his backgrounds give little sense of distance, often fading into solid gold. Because of this, and his harmonious color choices, Lochner is usually described as one of the last artists of the International Gothic style. This doesn't mean his paintings lacked the advanced techniques of northern art at the time. His arrangements are often creative. The worlds he paints are quiet, according to Snyder. This is achieved with balanced, soft colors and his repeated use of circles. Angels form circles around the heavenly figures. The heavenly figures' heads are very round, and they wear round halos. Snyder says the viewer is slowly "drawn into empathy with the revolving forms."

Because there are so few of his attributed works left, it's hard to see how Lochner's style changed over time. Art historians are not sure if his style became more or less influenced by Netherlandish art. Recent tree-ring dating of his works shows that his development wasn't a straight line. This suggests that the more advanced Presentation in the Temple is from 1445, which is earlier than the more Gothic Saints panels now split between London and Cologne.

Lochner's Artworks

Panel Paintings

Lochner's main works include three large polyptychs (multi-panel paintings): the Dombild Altarpiece; the Last Judgement, which is now broken apart and in different collections; and Nuremberg's Crucifixion. Only two paintings known to be his are dated: the 1445 Nativity now in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich, and the Presentation in the Temple from 1447, now in Darmstadt. There is a smaller, earlier version of the presentation scene at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon, dated 1445. As non-religious art became more popular and religious art less so in later centuries, 15th-century multi-panel paintings were often broken up and sold as single pieces. This happened especially if a panel looked like a regular portrait.

Wing panels and other pieces from Lochner's larger works are now in various museums and collections. Two surviving double-sided wing panels from an altarpiece showing saints are in London's National Gallery and the Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne. (The Cologne panels were cut in half so both sides could be displayed.) The wings of the Last Judgement originally had six parts, painted on both sides. They have been cut into twelve separate pictures. These are now divided between the Wallraf-Richartz Museum, the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, and the Städel Museum in Frankfurt. This work is probably from early in his career. Its subject and background are different from his other known works. While the parts are arranged in his typical harmonious way, the overall look and feel are unusually dark and dramatic. The Crucifixion is also an early work and reminds us of late medieval painting. It has a very decorated gold background and the smooth, flowing quality of the 'soft' Gothic style.

His surviving works often show the same scenes and themes. The birth of Jesus appears often. Several panels show the Virgin Mary and baby Jesus, often surrounded by a group of angels. In earlier panels, they are blessed by a hovering image of God or a dove (representing the Holy Ghost). In many cases, Mary is in her usual enclosed garden. Several paintings show the work of more than one artist. Weaker parts are thought to be by workshop members. The figures of Mary and Gabriel on the back of the Dombild were drawn more quickly and with less skill than the figures on the main panels. Their clothing is modeled with a certain "stiffness," and the cross-hatching "does not clearly define the relief" (the raised parts). A few drawings have been linked to him, but only one, a brush and ink drawing on paper from around 1450 called Virgin and Child (now in the Musee du Louvre), is confidently attributed to him.

Decorated Books

Lochner is connected to three surviving books of hours (prayer books): one in Darmstadt, one in Berlin, and one in Anholt. How much he was involved in each is debated; his workshop members probably did a lot of the work. The most famous is the Prayer book of Stephan Lochner from the early 1450s, now in Darmstadt. The others are the Berlin Book of Prayers from around 1444, and the Anholt Prayerbook, finished in the 1450s. These books are very small (Berlin: 9.3 cm x 7 cm, Darmstadt: 10.7 cm x 8 cm, Anholt: 9 cm x 8 cm). They have similar layouts and colors, and each is richly decorated with gold and blue. The borders are decorated in bright colors and have acanthus scrolls, gold leaves, flowers, berry-like fruits, and round pods. The Darmstadt book includes a full series of the Martyrdom of the Apostles. Its pictures show Lochner's typical use of deep blue, similar to his Virgin in the Rose Garden.

Art historian Ingo Walther sees Lochner's touch in the "pious closeness and deep feeling of the figures, always expressed so gently and elegantly, even in the extremely small size of the pictures." Chapuis agrees that they are by Lochner, noting how many of the small pictures share themes with his larger paintings. He writes that the illustrations "are not just a side thing. Instead, they deal with many of the ideas seen in Lochner's paintings and show them in a new way. There is little doubt that these beautiful images came from the same mind." The text of the Darmstadt book is written in the local Cologne language, while the Berlin book is in Latin.

Other Art Forms

There are old church clothes (liturgical vestments) with embroidered figures, including St. Barbara, that look like Lochner's style and have similar faces. This has led some to wonder if Lochner provided the designs. Also, some stained glass panels from that time look similar in style. There has been discussion about whether he might have painted church murals. The very large figures in the Dombild and Virgin with the Violet show he could work on a grand scale.

Two drawings on paper, one in the British Museum and one in the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, were once thought to be studies for the Munich Nativity. The lines of the clothing folds match those in the painting very closely, but the drawing skill isn't as good. The Paris drawing has paint smudges, suggesting it was a practice piece for workshop members. The London piece is better, but its lines are stiffer, lacking Lochner's smooth flow. So, its attribution has been changed to an artist closely connected to Lochner.

Who Influenced Lochner?

Lochner's art seems to have been influenced by two main sources: Netherlandish artists like van Eyck and Robert Campin, and earlier German masters like Conrad von Soest and the Master of Saint Veronica. From the Netherlandish artists, Lochner learned to paint realistic backgrounds, objects, and clothes. From the German masters, he adopted an older way of showing figures, especially women, with doll-like, expressive, and delicate features. This created "iconic, almost timeless" atmospheres, made even stronger by the old-fashioned gold backgrounds.

Lochner's figures have idealised facial features typical of medieval portraits. His subjects, especially females, usually have high foreheads, long noses, small rounded chins, neat blond curls, and noticeable ears. These features were common in the late Gothic period. This gives them the grand look of 13th-century art, placing them on what seem like shallow backgrounds.

Lochner probably saw van Eyck's Ghent Altarpiece from around 1432 when he visited the Netherlands. He seems to have used some of its ideas for his own compositions. The similarities include how the figures interact with their space and the focus on details like brocades, gems, and metals. Some figures in Lochner's paintings are directly taken from the Ghent Altarpiece, and some facial features match those seen in van Eyck's work. His Virgin with the Violet has often been compared to van Eyck's 1439 Virgin at the Fountain. Like in van Eyck's work, Lochner's angels often sing or play musical instruments, including lutes and organs.

However, he seemed to reject some parts of van Eyck's realism. For example, he didn't focus as much on showing shadows, and he didn't use transparent glazes (thin layers of paint). As a colorist, Lochner preferred the International Gothic style, even if this made his paintings less realistic. He didn't use the new Netherlandish techniques for showing perspective. Instead, he showed distance by making parallel objects smaller.

Lochner's Lasting Impact

Historical evidence suggests that Lochner's paintings were well-known and widely copied during his lifetime. They remained popular until the 1500s. Early ink drawings based on his Virgin in Adoration are in the British Museum and École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts. You can see Lochner's influence from his Last Judgement in Hans Memling's Gdansk altarpiece. The gates of Heaven look similar, as does the way the blessed people are shown. Albrecht Dürer knew about him before his visit to Cologne, and Van der Weyden saw his paintings during his trip to Italy.

The Heisterbach Altarpiece, which is a set of wings now taken apart and divided between Bamberg and Cologne, owes a lot to Lochner's style. The inner panels show sixteen scenes from the life of Christ and of the Virgin Mary. These scenes have many similarities to Lochner's work, including their shape, how they are composed, the faces of the people, and the colors. For a while, this work was thought to be by Lochner himself. Now, it's generally agreed that it was strongly influenced by him. In 1954, Alfred Stange called the Master of the Heisterbach Altarpiece Lochner's "best-known and most important student and follower." However, research in 2014 suggests that the two artists might have worked together on the panels.

Research in 2014 by Iris Schaeffer looked at the underdrawings of the Dombild Altarpiece. She found two main artists' hands, likely Lochner and a very talented student. She believes this student was probably the main artist behind the Heisterbach Altarpiece. Another idea is that Lochner's workshop was working on a tight deadline, and he simply let others do some of the work to finish on time.

Gallery

-

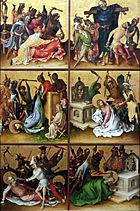

"Martyrdom of Andrew the Apostle", Martyrdom of the Apostles, around 1435–40, Städel, Frankfurt.

-

"Martyrdom of Saint John", Martyrdom of the Apostles, around 1435–40, Städel, Frankfurt.

-

"Martyrdoms of Simon the Zealot and Jude the Apostle", Martyrdom of the Apostles, around 1435–40, Städel, Frankfurt.

See also

In Spanish: Stefan Lochner para niños

In Spanish: Stefan Lochner para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |